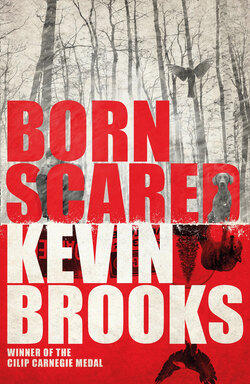

Читать книгу Born Scared - Kevin Brooks - Страница 6

2 LESS THAN NOTHING

ОглавлениеMy fear pills are yellow, which isn’t a bad colour for me.

Red is blood (and Santas), black is death, blue is the drowning sea . . .

Yellow is cheese and bananas.

And pills.

I don’t know why I call them fear pills. They’re anti-fear pills really.

I’m chronically afraid of almost everything.

Sometimes I think I can remember being scared when I was still in my mother’s womb. It’s not much more than a distant feeling really – and I have no idea what I could have been frightened of in there, or how – in my unformed state – I could have perceived it.

Unless . . .

Unless.

It’s probably more accurate to say that I sometimes think I can remember being scared when we were still in our mother’s womb. There were two of us in there: me and my sister, Ellamay. We were twins, and I know in my heart that my embryonic fears – if that’s what they were – were as much Ellamay’s as they were mine.

We were scared.

Together.

We were as one.

As we still are now.

And perhaps we knew what was coming. Perhaps we were frightened because we knew one of us was dying . . .

No, I don’t think that’s it.

I don’t think any of us knows what death is until it’s explained to us. And the strange thing about that is that although there must be a pivotal moment in all our lives when we find out for the first time that all living things die, and that at some point in the future our own life will come to an end, I certainly can’t remember the moment when I found out, and I’d be surprised if anyone else can either.

Which is kind of weird, don’t you think?

What I can remember though is the effect that moment had on me.

I don’t know how old I was at the time – four? five? six? – but I clearly remember lying in bed at night with my head beneath the covers trying to imagine death. The total absence of everything. No life, no darkness, no light. Nothing to see, nothing to feel, nothing to know. No time, no where or when, no nothing, for ever and ever and ever and ever . . .

It was terrifying.

It still is.

. . . lying there for hours and hours, staring long and hard into the darkness, searching for that unimaginable emptiness, but all I ever see is a vast swathe of absolute blackness stretching deep into space for a thousand million miles, and I know that’s not enough. I know that when I die there’ll be no blackness and no thousand million miles, there won’t even be nothing, there’ll be less than nothing . . .

And the thought of that still fills my eyes with tears.

But sometimes . . .

Sometimes.

Sometimes it feels as if that memory doesn’t belong to me, that it happened to someone else. Or maybe I read about it in a book or something – a story about a mixed-up kid who lies in bed at night trying to imagine death – and I identified with it so much that over time I gradually convinced myself that I was that mixed-up kid, and his imaginations were mine.

Not that it makes any difference, I suppose.

A memory is a memory, wherever it comes from.

I’ve sunk down to the hallway floor now, and I’m just sitting here with my eyes closed and my back against the wall. I’m trying to breathe steadily, trying to calm my thumping heart, trying to empty my mind.

After a while Ellamay comes to me, her silent voice as comforting as ever.

It’s all right, Elliot. It’ll be okay.

‘I’m scared.’

I know. But you won’t be alone. I’ll be with you all the way.

‘I don’t think I can do it.’

Yes, you can.

‘It’s too much.’

You have to do it, Elliot.

‘I know.’

For Mum.

‘I know.’

For us.

We were born prematurely, at twenty-six weeks. I weighed just under a pound, Ella was even smaller. It was a traumatic birth, and at first the doctors weren’t sure if any of us were going to survive. Mum had lost a lot of blood and was in a really bad way, and while she was rushed off for an emergency operation, Ellamay and I were taken to the neonatal intensive care unit where we were put in incubators and hooked up to all kinds of stuff to keep us alive.

It didn’t work for Ellamay.

She only lived for an hour.

I almost went with her.

Our hearts stopped beating at virtually the same time. But although the doctors and nurses somehow managed to save me, they couldn’t do anything to bring Ella back.

Part of me died with her, and part of her lived on with me.

We’re dead and alive together.

The first time I experienced fear in the outside world – as opposed to the inner world of my mother’s womb – was the first time I woke up in the incubator after Ella had died. It’s a moment that’s as much a part of me as all the other things that make me what I am – my heart, my brain, my flesh, my blood.

I was just lying there – on my back, my eyes open – looking up through the clear-plastic dome of the incubator at the white sky of the ceiling above. Muted sounds were drifting all around me – soft beeps, hushed voices, a low humming – and although I didn’t know what these noises were, I wasn’t scared of them. They were the sounds of my world, as normal to me as the sound of my own stuttered breathing.

Then, all at once, everything changed.

The white sky suddenly darkened as three unknown things appeared out of nowhere and loomed down over me. I didn’t know what they were – moving things, menacing things, things that made strange jabbering noises – wah thah . . . pah banah . . . al tah plah . . . tah yah ah lah . . .

Monsters.

Then one of them moved even closer to me, stooping down over the incubator, getting bigger and bigger all the time . . . and that was when the fear erupted inside me. It was uncontrollable, overwhelming, absolute.

Pure terror.

It was all I was.

The three unknown things that day were my mum, her older sister Shirley, and Dr Gibson, and the funny (peculiar) thing about it is that although they were the first people to scare me to death, they’ve since become the only three people who don’t scare me to death.

They are, to me, the only true people in the world.

Everyone else is a monkem.