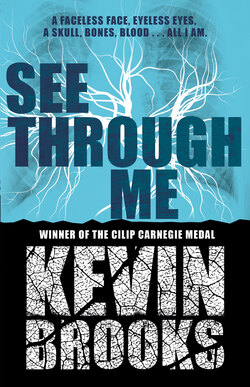

Читать книгу See Through Me - Kevin Brooks - Страница 11

6

ОглавлениеI don’t think I’ll ever get used to the way I am, and even now there are still things I shudder to see, but if you live with your inner self for two long years – seeing the life inside you every single day – you can’t help growing to admire it. You might still hate it – or at least what it’s done to you – and you might not find it quite so grotesque anymore (though you know it’s still hideous to others), but at least you can appreciate its wonder. How do all those things inside me know what they’re doing? How do all those mindless lumps and blobs and tubes keep going? And if I have no control over them, which I don’t – I don’t even know what most of them actually do – who or what does control them?

I’ve also come to realise that no matter how I feel about the things inside me – whether it’s wonder or hatred or anything else – their only purpose is to keep me alive, and they do their job with such tireless devotion that it seems a bit heartless to hold anything against them.

Unless, of course, you don’t want to be kept alive.

But I’ll come to that later.

All I’m trying to say now is that it’s taken me a long time to even begin coming to terms with the way I am, and while that doesn’t really mean much more than being relatively okay with it most of the time, it’s a whole world away from the devastating horror and hopelessness that was all I had in the weeks and months after that day of revelation at the RDRT Centre.

And as for the revelation itself . . .

Words aren’t enough.

It was beyond words.

Beyond description.

Beyond all understanding.

Dr Reynolds was true to his word – he worked very slowly, taking his time, revealing my condition inch by inch, hand by hand, limb by limb . . . all the time checking with me to make sure I was still okay to go on, and pausing at regular intervals to let Dr Hahn look me over and decide whether or not I was too traumatised to continue.

The initial shock – the revelation of my lower arm, wrist, and eventually my hand – was tempered only slightly, if at all, by the fact that it wasn’t a complete surprise. I’d already seen the meat and muscle of the upper halves of my legs, and the half-hidden bone of my kneecaps . . . and I’d already seen my skull in the mirror too – faceless, skinless, screaming . . .

But this was different.

This was right here, right now, right in front of my eyes . . .

My arm and hand, skinless things of meat and muscle, the living redness framed in the white of the pillow.

And this time there was no doubting it.

My mind and my senses were perfectly clear. I wasn’t sick. I wasn’t half crazy with pain. And I knew I wasn’t just seeing things, because when I looked up and gazed around at the three doctors, I could see the extraordinary truth in their eyes.

‘What is it?’ I managed to mutter, staring down at my hand. ‘What’s happened . . . my skin . . . what’s happened to my skin?’

‘We don’t know yet,’ Dr Reynolds admitted. ‘We’re looking into the possibility that it might be some kind of genetic disorder, but as far as we can tell there are no known records of any condition – genetic or otherwise – that presents with symptoms anything like yours, which basically means we’re looking for answers to questions that have never been asked before. And unfortunately that takes time.’

He stopped for a moment, watching closely as I tentatively moved my hand, turning it very slowly until the palm was facing up. It looked inhuman – like the inner workings of a demonic claw.

‘Try moving your fingers,’ Dr Reynolds said.

I waggled them a bit, then cautiously closed my hand, forming a loose fist. I held it for a second or two, then opened my hand again.

‘Did you see it?’ Dr Reynolds asked.

‘See what?’

‘If you look very hard you can just about see the outline of your skin. It’s incredibly faint, and it’s only really visible when you move. But it’s definitely there.’

I tried again, this time moving more freely, and after a few moments I saw what he meant – an almost imperceptible flickering of hand- and finger-shaped outlines, barely more than fleeting shimmers, like the outline of a glass hand in crystal-clear water.

‘It’s pure transparency,’ Dr Reynolds said, unable to keep a whisper of awe and admiration from his voice as he gazed at my hand. He carried on staring at it for a few moments, then gave a little shake of his head and turned to me. ‘There’s doesn’t seem to be anything actually wrong with your skin, or any other affected tissue. Every test we’ve done shows that the structure and function of the transparent cells is perfectly normal. Of course, I realise that’s of no consolation to you, but –’

‘Am I like this all over?’ I said.

He froze for a second, his eyes blinking and his mouth half open, and that was all the answer I needed.

I didn’t look at everything that day – there were parts of me that I simply couldn’t bear to see – but I saw more than enough to confirm the unthinkable truth. The skin of my entire body was transparent.

I knew very little about human anatomy then, so I couldn’t put a name to a lot of the things I saw, but as more and more of my inner self was revealed, the more it seemed that most of it looked much the same.

Muscle . . .

Flat bands of fibrous red, the redness blotched with the dull yellow shine of fat.

The pale gristle of cartilage.

And in places with little or no covering of muscle – knuckles, knees – the shadowy white presence of bone.

And I seem to remember that it was this – this basic sameness of my inner body’s landscape – that drifted into my mind as I gazed down numbly at the skinless vision of my belly.

At least, I remember thinking . . . at least you can’t see any deeper inside yourself.

Imagine that . . .

Imagine the horrors lying in wait beneath that canopy of muscle.

And it was then – just as that very thought came to me – that Dr Reynolds made another revelation.