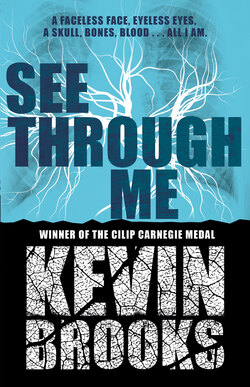

Читать книгу See Through Me - Kevin Brooks - Страница 13

8

ОглавлениеI came very close to putting a stop to everything then. I’d had enough. My brain was too scrambled to think anymore, and all I could feel – physically and emotionally – was a numbing cold sickness that felt like the end of the world.

I wanted to be left alone now. I wanted to lie in the darkness and not think or feel anything at all. I wanted to empty myself of everything and float off to a place where things were still all right.

But I knew that I couldn’t.

Not yet anyway.

Not until I’d seen the skull in the mirror.

‘I’d strongly advise against it,’ Dr Hahn told me. ‘You’re already highly distressed – understandably so – and another major shock to your system now could have very serious consequences. On the other hand . . .’ She paused, her eyes fixed on me, her lips pursed in thought. ‘I completely understand why you need to do this – if I was in your position I’d feel the same – and it doesn’t make any difference what I say to you anyway, does it?’

‘No.’

‘You’ve already made up your mind.’

I nodded.

‘And if we don’t do it now, you’ll find a way to do it on your own later on.’

‘It’s my face . . . my head. It’s me. I can’t not know it.’

The only time I cried during the whole revelation was when Dr Kamara told me that I’d lost all my hair. And by lost she meant lost. Not just transparent, but gone . . . every last bit of it. For some reason – which they still didn’t understand – it had all fallen out when I’d been half crazy with sickness and pain.

Dr Kamara told me this before I’d looked in the mirror, and I know it might seem like a strange thing to warn me about – that having no hair should be the least of my worries – and from the look Dr Reynolds gave her when she told me, a puzzled frown, it was perfectly clear that he didn’t get it. But Dr Kamara knew what she was doing. She knew that the shock of losing my hair wouldn’t be the same as the shock of everything else. Everything else was extraordinary, impossible, unbelievable. Losing my hair was real. It was something I could understand, something I could have real feelings about . . . feelings that actually made sense.

If Dr Kamara hadn’t warned me in advance, those feelings would have got mixed up with all the unbelievable stuff, and I would have missed the chance to have some true sadness and grieve a little for what I’d lost.

My hair . . .

My lovely, stupid, midnight-black mess of hair.

All gone.

I loved that hair.

I really did.

But even as I sat there crying my eyes out, I couldn’t help wondering how my tears must have looked as they streamed down my skinless face.

They must have planned to show me my head – or at least planned for the possibility – because Dr Hahn just went into the little bathroom and almost immediately came back out again carrying a medium-sized frameless mirror. As she walked back over to the bed, she kept the reflective side facing towards her, and as Dr Reynolds stepped aside to let her stand next to me, she held the mirror close to her body, clutching it almost secretively to her chest, as if my reflection was already in it and she didn’t want me to see it yet.

I know she spoke to me then – I remember seeing her lips move – but I have no idea what she said. All I could hear as she stood there talking to me was a surging roar inside my head and the deafening thump of my heart. Everything else was just a distant drone.

I don’t remember how the mirror came to be in front of me either.

I don’t know if Dr Hahn just gave it to me, and I held it in front of me, or if she positioned it for me and held it herself . . . or if it was all done gradually, revealing my reflection bit by bit, or if there was no hesitation at all, just a straightforward no-nonsense revelation . . .

I have no recollection at all.

I remember the roar in my head . . .

I remember the fear in my heart . . .

And then suddenly I was back home again . . . standing at the bathroom sink, my head crashing with electric madness, staring at the nightmare vision in the mirror.

A skull, skinless . . . white bone, grinning teeth . . .

Eyeless . . .

Faceless . . .

Hairless . . .

A skull, pocked with grey stuff and schemes of blood . . .

A thing of death.

It was me.

I could see the tracks of my tears running from the holes where my eyes used to be, the holes looking back at me like caves of bone. I knew my eyes were still there, but it’s hard to believe in something you can’t see.

I closed them.

Something might have flickered in the mirror, just the tiniest shimmer of unseen movement as my invisible eyelids closed . . . but nothing changed. I still couldn’t see the things I was seeing with.

It was too much.

I didn’t want to see anymore.

I covered my eyes with my hands, desperate for the sanctuary of darkness, but all I got was a blurred transparency of finger bones and muscle and blood. The skull in the mirror was still there, still grinning at me through the glaze of my see-through hands . . . and I knew that I didn’t have to keep looking at it, that all I had to do was turn my head and look away, but no matter how much I wanted to – and in that moment I’d never wanted anything more – I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t do anything. Couldn’t move, couldn’t breathe, couldn’t feel, couldn’t speak . . .

Kenzie?

A voice from a million miles away.

Kenzie!

Your face is who you are. It’s your identity, the thing that makes you you. It’s how you see yourself . . . which is kind of strange, if you think about it, because your face is one of the few parts of your body that you can’t actually see, and the only way you know it is through the second-hand imagery of other things – mirrors, photographs, videos . . .

But it’s still how you see yourself. And it’s how everyone else sees you and knows you too. Your face is you. And because you see it so many times every day – and you’ve been seeing it every day for most of your life – you know it more intimately than anything else. You know every millimetre of it – every line, every turn, every shape . . . the way it all fits together. You know it so well, and it means so much to you, that if it changes in any way at all, you’re instantly and intensely aware of it. And if that change is enough to disturb the familiarity of your face – and it doesn’t take much to do it – the effect can be staggering.

The thing that’s you, and has always been you, has suddenly become something else. It’s not you anymore . . .

That you has gone.

And now you’ve become this . . .

This fucking thing.

I hit it.

My head cracked.

And then I was nothing.