Читать книгу See Through Me - Kevin Brooks - Страница 6

1

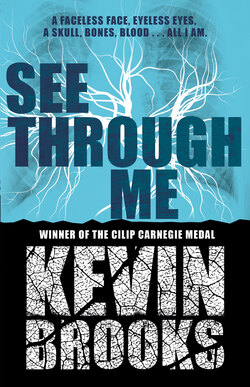

ОглавлениеMy name is Kenzie Clark.

I’m eighteen years old now (it was my birthday last month), and sometimes I forget that my last day of normality – the last day of my life as a relatively ordinary girl – was only two years ago. It doesn’t feel like two years. It feels like a lifetime, like I’ve been like this for ever. And sometimes, when I think back to the days before the horror, I find it almost impossible to remember the ‘me’ I used to be – the child, the teenager, the girl who wasn’t like this. It’s as if she never existed. I’ll be lying awake at night, staring into the darkness, trying to picture her . . . trying to remember how she looked, how she was, how she felt about things . . . and nothing of her will come to me.

All I’ll see is all I am.

A faceless face, eyeless eyes, a skull, bones, blood . . .

All I am.

A lot of my memories of the day it happened are either shattered beyond recognition or buried so deeply that I doubt they’ll ever come back, but I know it was a rain-sodden Sunday – I remember getting soaked when I went to the corner shop to get Dad’s newspaper – and I’m fairly sure that it started out as just another day.

I would have got up at the usual time – around seven o’clock – and before doing anything else I would have checked on Finch, my younger brother, just as I did every morning. We shared a bedroom, so all I had to do to make sure he was okay was get out of bed and shuffle across to his side of the room. If he was still asleep I would have left him, and if he was awake, which he usually was, I would have asked him how he was doing and if there was anything he needed – water, the toilet, any painkillers or anything. I can’t recall how he was that morning, but I’m pretty sure I’d remember if it had been one of his really bad days, because that was the only time he ever showed how much he was suffering. The rest of the time he kept it to himself, and most mornings he’d just give me a tired smile and tell me he was fine.

I can still hear his voice sometimes . . .

Hey, Kez . . .

. . . all weak and croaky.

How’s it going?

And always that smile . . . the one just for us. Like a momentary light in the gloom.

The day would have passed like any other Sunday – looking after Finch, helping Dad with the housework . . . cleaning, cooking, washing and ironing, sorting out my school clothes for tomorrow. I probably had some homework to do – I usually left it till Sunday – and I know for sure that as the day wore on I would have started feeling worse and worse about going to school on Monday. Not because of the homework – I never had any problems with that – but simply because of all the crap I was going through back then. The nastiness, the taunts, the lies . . . the sickening knot that twists in your stomach when you see the faces you don’t want to see . . . and you know you should just ignore it all – it’s nothing, they’re nothing . . . it’s a waste of time even thinking about them . . .

But you can’t help it, can you?

It hurts.

You’d think it wouldn’t bother me so much anymore. Now that I’m like this – and being like this is a thousand times worse than anything I had to put up with before – you’d think all the hurt that I went through back then would have paled into insignificance. But it doesn’t work like that. It’d be nice if it did – it might have given me a small crumb of comfort now and then – but it doesn’t.

I was alone in the house with Finch when it happened.

One of the reasons I know it was a Sunday is that Dad wasn’t home that evening. Sunday nights were his ‘night off’, which meant that as long as Finch was relatively okay Dad would leave the house around seven o’clock and head off to the George and Dragon. It was his local pub, no more than a fifteen-minute walk away, and he’d been a regular there for years. He was in the darts team, the pool team, the quiz team . . . he’d even played in goal for the pub’s football team a couple of times. He didn’t drink very much – I don’t think I ever saw him drunk – he just liked being in the pub, being with his pub-friends, being what he used to be before it all went wrong. He used to go to the pub at least two or three times a week when Mum was still here and Finch wasn’t so bad, but since then he’d gradually cut it down to just the one night. I can’t remember when – or why – the one-night-a-week had become Sunday-night-only, but by the time of that rain-sodden Sunday two years ago, the routine was always the same. At six-thirty Dad would stop whatever he was doing. At six-forty he’d have a shower and change into his going-out clothes – jeans, polo shirt, fleece if it was cold. At six-fifty he’d check on Finch to make sure he was okay, then he’d have a few quick words with me – Call me if you need me, I’ll be back by twelve – and off he’d go.

I can’t really remember what I did between seven and nine o’clock that night. There’s a picture in my mind that shows me sitting at the kitchen table doing my homework, but I don’t know if it’s a true memory or just something I’ve imagined so many times that it’s become my truth. Not that it makes any difference. Wherever I was, and whatever I was doing, I know – I know – that at nine o’clock I was sitting on my bed staring stupidly at my phone.

My memory of that moment is seared into my mind.

I was sitting with my back against the wall, my knees drawn up to my chest, and the clock on my phone read 21:02. My thumb was hovering over the yapTee icon (yapTee was the messenger app that we all used back then), and a pulse was throbbing in the back of my head.

They’re nothing, I kept telling myself. They’re not even worth thinking about . . .

But the ever-tightening knot in my stomach told me otherwise.

‘Why don’t you just get rid of it?’ I heard Finch say.

I looked over at him. He was half sitting up in his bed, a paperback book in his hand.

‘Get rid of what?’ I said to him.

He just smiled. He knew that I knew what he meant. He’d been telling me to keep off yapTee ever since all the nasty stuff had started. He couldn’t understand why I kept looking at it when I knew what I’d find, and I knew it would make me feel terrible.

I couldn’t understand it either.

‘You should get rid of all of them,’ Finch said. ‘Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat . . . just shut them all down. You don’t need them, do you?’

‘Well, no . . . but –’

‘Give it to me,’ he said, holding out his hand for my phone. ‘I’ll do it for you.’

‘No, it’s all right,’ I told him. ‘I’m putting it away now anyway.’ I shut off the phone and put it in the pocket of my hoodie. ‘See? It’s gone . . . easy.’

‘Yeah, but it’s still all there, isn’t it?’ He smiled again. ‘Come on, Kez, just give me the phone . . . it won’t take a minute. You know I’m right, don’t you? I’m always right. That’s why . . .’ His smile suddenly faded and his voice became urgent. ‘What’s the matter, Kenzie? Kenzie? What’s going on?’

I didn’t know what was going on. All I knew was that everything felt wrong – my skin, my head, my hands, my eyes . . . everything felt like nothing I’d ever felt before. Every cell in my body – inside and out – was shivering, tingling, burning, freezing . . . hot and cold together . . . clammy and sick . . . electric . . .

Indescribable.

Jagged flashes were cracking through my skull – shapes and sounds together – and the room was melting and spinning . . . there but not there, sizeless, whirling . . .

The air was a roar of silence.

Beyond silence.

I could hear a voice – deep and slow, distorted . . . the nightmare voice of a giant – and it was coming to me from nowhere and everywhere, from a million miles away and no distance at all, the sound of it soaking into me through my skin . . .

It was Finch.

I know that now. He told me later that as he’d tried to help me – scrambling out of bed and into his wheelchair, wheeling himself across the room – he’d kept on calling out to me, screaming and yelling at the top of his voice, but no matter how loudly he’d shouted, I’d just sat there on the bed, my head in my hands, oblivious to everything.

‘It was really scary,’ he told me. ‘Your face, your hands . . . there was this weird kind of shimmery paleness to your skin, like a . . . I don’t know . . . like a milkiness. Or a cloudiness or something. Like your skin was floating.’

He also told me that just as he reached me, just as he was manoeuvring his wheelchair alongside the bed, I suddenly groaned, doubling over and clutching my belly, and a moment later I scrabbled off the bed, almost falling over as I got to my feet, and the next thing he knew I was stumbling across the room – stooped over, still clutching my belly – then lurching out through the door and along the landing towards the bathroom.

I don’t remember that.

I remember being in the bathroom though – bent over the sink, retching and heaving, my ice-cold face streaming with hot sweat. My insides were wracked with a strange swell of nausea that kept surging up into my throat then erupting into nothing, so all I kept doing was sicking up gobs of horrible brown phlegmy stuff. And every time the sickness surged, and every time I retched, a wrenching pain ripped through my belly. And all the time my skin was shivering and prickling . . . hot but not hot, cold but not cold . . . and my head was still crashing with electric madness, flashing and cracking with bolts of black lightning . . . and then all at once, just for a moment, everything seemed to stop – no movement, no sound, no pain, no time – and all I can remember is staring down at my hands as they gripped the sides of the sink, wondering distantly why my fingers were as white as the porcelain . . .

Then out of nowhere a sudden massive spasm shot right through me, and as I jerked upright – my back stretched tight – I came face to face with a nightmare vision staring back at me from the mirror above the sink. A skull, skinless . . . white bone, grinning teeth . . .

It wasn’t me.

It was a human skull.

Faceless, stripped . . .

Muscled red . . .

It couldn’t be me.

But it was moving with me . . . turning as I turned, leaning closer to the mirror with me, its lipless mouth dropping open in horror with mine . . .

And it had my hair.

It had my stupid dyed-black hair . . .

It wasn’t real. I knew that. There was something wrong with me, that was all. I was sick, feverish, hallucinating . . . my head was all messed up. All I had to do was close my eyes and take a few deep breaths . . .

I closed my eyes.

Nothing happened.

I could still see.

I opened my eyes and closed them again, squeezing them shut as tightly as possible . . . but it didn’t make any difference. I could still see. And I realised then that I was seeing through my closed eyelids . . .

The skull in the mirror opened its mouth and screamed.