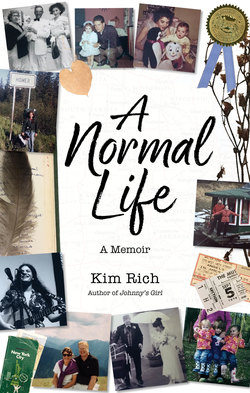

Читать книгу A Normal Life - Kim Rich - Страница 7

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Neverland

Not long ago, I met an old friend from Alaska for coffee in Los Angeles, where I was visiting family. Brent and I knew each other as teens. For what seemed forever, I had an overwhelming and obvious crush on his brother, much to his brother’s dismay. I was not the girl everyone wanted to date. With naturally curly brown hair and no hair dryer (and no idea how to use one), I didn’t fit the Farrah Fawcett blown-dry, swept-back blonde look popular at the time.

If I had someone to show me how to make my hair look like that, I might have tried. But I was raised by my dad, with intermittent influence from his cocktail-waitress or topless-dancer girlfriends, and one wonderful second wife who lasted less than a year, when my father’s explosive rage drove her away. The girlfriends were not much help in the “how to be a girl” department. Go-go boots and fringe and pasties? I don’t think so.

In junior high school, I thought Brent was too good-looking for me. He was also a really nice guy, then and now. He is the kind of friend who would race out of his house at nearly the last minute and drive across LA to catch a quick cup of coffee with an old friend. I hadn’t seen him in about forty years. Forty years.

I brought two of my young teen daughters with me—a mistake, Brent and I realized as soon as we sat down to reminisce.

The two of us grew up in Anchorage in perhaps one of the toughest eras to be a teen in America, right after the Sixties. The decades—and their pop cultural influences—don’t neatly start and end when the calendar turns over. The turbulence and challenges of the late Sixties snowballed into the following decade, picking us up along the way.

“Oh, God, Kimmy, remember all the parties—ah, I mean, ah…”

“Bible group meetings?”

Our conversation drifted into reliving get-togethers—ah, parties… ummm, Bible study sessions—where we would listen to Led Zeppelin.

“Your mom and I never…” Brent said, turning to the girls in the middle of our conversation.

“Oh, God, no,” I muttered, shaking my head in case they might have been paying attention. Never fear. Their heads were buried in their smartphone screens.

So, Brent and I took the G-rated journey down memory lane that night. We marveled how we’d both gone to the first concert we had ever been to—Jefferson Airplane. I was twelve, I think, and in seventh grade. I went with a woman friend of my dad’s.

At one point, Brent turned to my two daughters and said, “Your mom was a rebel!”

They smiled politely and returned to their smartphones and videos.

I was struck by the label. Rebel. Me?

All I ever wanted was a normal life.

THE LAST TIME I had seen Brent, and many of my friends from junior high school, was late summer 1973. That August, my father was kidnapped and murdered.

That was the end of anything resembling a normal teen life.

The police didn’t make any arrests of his captors and killers until November. That fall, I lived a life I can only describe as akin to the Lost Boys in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan.

I lived in Neverland.

Before my father’s disappearance, he spent most of his time at the living quarters in one of his “massage parlors.” I was left at our house—a large, two-story, ugly brown mess of a place at 736 East Twelfth Avenue. It was also known as the 736 Club, the name of the after-hours gambling parlor he operated there when I entered middle school.

Most kids want to live in a candy shop. I got a casino.

I hated the place from the moment we moved in. It was always dark inside. There were few windows, and except for one window in the kitchen, they had all been boarded up by my dad or closed with tight shades. He wanted to keep prying eyes from seeing the illegal activities going on inside.

Even my sole bedroom window was boarded up. To this day, I do not close curtains or blinds during the day in any house where I live. I cannot stand to be shut in. I don’t even close up my house after dark.

Even now, I have nightmares about the place. The dreams are always the same: I am back in that house, which is usually remodeled and made to look so different that it’s unrecognizable. Unrecognizable to anyone but me, that is. In these dreams, I know what lies under the shiny new furnishings. In these dreams, I wonder at whatever form the house has taken, marvel at how it doesn’t look the same, and feel a vague sense of unease, disorientation, and fear that one day I might end up there again.

IN THE EARLY 1970s, Anchorage was a hard-working town of about 147,000 people. Its slapdash post-war, post-earthquake buildings hunkered between the majestic peaks of the Chugach Mountains and the muddy waters of Cook Inlet. The entire state was poised to begin making big money working on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. My dad was ready to make big money off the workers.

When I was twelve or thirteen, the 736 Club opened every morning after the bars closed, around 5 a.m. It stayed open until late morning or until everyone left. The illegal gambling club was set up in two connected rooms that made up what must have originally been the home’s dining room and living room. My dad hung a colored beaded curtain to divide the two. Tasteful, I thought.

In the first room were secondhand couches where patrons sat, drank, and relaxed. The other room had a craps table and large poker table. When not in use, the poker table wore a laminated wood cover my father would slip on to protect the table’s expensive padded green surface. In my memory, the rooms are crowded, smoky, noisy.

By the time I was fifteen, the 736 Club was no longer operating. Arguments between my dad and me had grown more frequent, and he became physically violent. I left the house and went to the authorities. I returned when he promised to close the club and seek counseling for his anger issues.

While my dad spent most of his time keeping an eye on business at the massage parlors, he still kept a bedroom at our house. Another bedroom was mine, and my dad’s friend, Al, and his girlfriend lived in the third. Al was a longtime friend who parented me perhaps more than my father ever had. He got me up for school. He got me off to my after-school job at the nearby gas station. He cooked dinner every night. Al and I remain close to this day.

But after my father’s kidnapping, Al was gone, pushed out by my dad’s last wife, Bridget. They had just married that summer, when she was pregnant. Bridget didn’t stay long either, perhaps because we did not get along. She was barely seventeen, about a year older than me.

My dad routinely dated gorgeous women—cocktail waitresses and topless dancers and strippers and such. Bridget looked twenty-one or older. She’d been on the streets for years, which probably gave everyone—including my dad—the impression she was old enough. Just barely. Her convoluted life included the baby born after my father disappeared, a child who was believed to be my father’s son.

Bridget was my own version of a fairy-tale evil stepmother. Soon after it was clear my father wasn’t coming home, Bridget moved in some friends of hers to rent one of the bedrooms. They were a couple. A man and a woman. They were also heroin addicts; he was a pimp, and she worked as a prostitute.

My friends and I called them “the vampires” because they only came out after dark. We managed to avoid them most of the time; thankfully, they weren’t interested in socializing with teenagers. When they finally moved out, they left the carpeting littered with bloodied cotton balls and empty syringes.

I started school that fall on my own, but soon Bridget came around and tried to parent me. I would have none of it, because she was also looking for the Social Security checks that came in the mail for me after my mother’s death a year earlier.

We would fight, and she would threaten to “call the authorities” and have me picked up and thrown into juvenile detention or foster care. Of course, I had no business living without adult supervision—I’ll give her that. But I’d be damned if that supervision came from her.

It wasn’t long before she, too, disappeared from my life, as well she should have. She had been a heroin addict before meeting my father and became one again after his disappearance.

So, while everyone who gave it any thought at all probably assumed Johnny’s new wife was taking care of Kim, Kim took care of herself.

That winter, other runaway and castaway teens came and went from the house on hearing from one friend or the other that it was an adult-free zone. Some stayed a day or more, some longer. The whole place came to look like an average teenage room—a mess. I’m neat and clean, but somehow the house fell into chaos, with clothes, shoes, even garbage strewn about.

Whenever anyone had some money, we might walk across the street to the grocery store and get some things. A big splurge would be to go over to Mark’s Drive-In to buy the “Mark’s Special,” a hamburger, fries, and milkshake. But mostly our pockets—and the cupboards and refrigerator—were empty.

I have gone hungry twice in my life. The first was when I was about six. I can’t remember whether it was for just a morning, a whole day, or longer, but no one seemed to be around to make me anything to eat. My mother was in bed, having fallen into a deep depression and probably a psychosis, as she slowly slipped into schizophrenia. I ate all the frosting off a cake in our fridge. Later I dumped a box of tapioca in a bowl, added water, and ate it.

The second time was that fall of 1973.

I got by somehow on the money I made at my after-school job at the gas station. The utility bills just went unpaid until six months later, when I finally left the house once and for all.

How I hated that house. I would have friends drop me off down the street so no one could see where I lived. I felt depressed about my life, and why not? I was a fifteen-year-old girl, full of angst and self-loathing, with a toilet that had stopped working in the house’s only bathroom.

Fortunately, it was the middle of winter, and the temperatures were below freezing. My response to the toilet problem was to scoop the toilet bowl contents into a mop bucket using an old kitchen ladle. Then I’d take the slop to the carport on the side of the house and set the bucket there to freeze. Later, I’d dump it upside down and do it all over again, leaving the frozen and growing blob of sewage to sit there until the spring thaw.

This could have gone for days or weeks. I don’t recall. Ironically, I was a clean kid. Before my dad disappeared, I had always kept our house tidy.

SOMEHOW, I MANAGED to get up every day and go to school for my tenth-grade classes at East High School. My bus was full of African-American students from Fairview, Anchorage’s largely black neighborhood.

I was scared to death the first time I got on the bus. I had no friends from the neighborhood, never had any. Fairview was full of government housing projects and low-income housing and some modest, working-class homes. Many of my fellow East High students on my bus were streetwise; like me, many were veterans of lousy childhoods.

One day, I mouthed off to the bus driver over something. That drew the attention of one tough black girl who intimidated me. But after that, she decided I was all right, and we sat together from then on.

At school, I kept my head down in class and did my work. I enjoyed art class the most, where a kind teacher named Bonnie, with long, blonde hair and a gentle nature, looked after me.

When home, I did what teens do—I listened to music a lot and talked on the phone. I recall listening over and over again to Neil Young’s two albums Harvest and Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

I’d sing along to the former; the latter certainly described life at the new 736 Club, home to wayward teens.

I might not have made it through those months if not for my best friend at the time, Dean.

Dean and I began hanging out in middle school. I was friends with his younger sister, René, and became close to their family: their mom, Sue, her husband, Bernie, and two adorable little brothers, who I would sometimes babysit.

Then and for years after, Sue was like a mom to me; René, a sister; and the younger boys were like my little brothers.

Dean had dark hair worn in a short ponytail. He was handsome, with a little air of mystery, having spent some time in a juvenile facility for some minor behavioral issues.

I initially had a crush on him, as did many girls. But until my late teens, when we went out for a short while, we were always just friends. Good friends.

In 1973, Dean’s family moved to Seattle, and he went to Oklahoma to live with an older brother. Dean was half Cherokee Indian on his mother’s side. If he graduated from high school in Oklahoma, he could go to college tuition-free, he told me.

But then he learned my father was missing. One day, I heard a knock on the door, and there he stood.

He came back to stay at the house that fall until he couldn’t miss any more school and had to go back.

It was a relief to have someone I could rely on in that house.

That Thanksgiving, Dean’s mother had a friend stop to check on me and deliver a turkey. I was embarrassed when I let him in. For the first time, I realized how deplorable the place looked. That nice man didn’t even blink. He just smiled and gave no indication of the horror he surely must have felt seeing me alone in that house full of debris and neglect.

THERE WERE MOMENTS that winter when a normal life seemed possible. For Christmas, Dean’s family bought me a ticket to spend the holiday with them in Seattle. It remains a cherished memory. Sue and Bernie bought René and me a generous number of matching gifts, including clothing and jewelry. It was one the best Christmases I had ever had.

When I turned sixteen in, friends planned a birthday party for me. They created a restaurant-like atmosphere in the living room of the 736 Club, complete with a waiter and a home-cooked meal.

But the real Sweet Sixteen party was the one I planned.

Some of the Lost Boys, as I now call them (some of whom were girls), had moved on from the 736 Club, but I had plenty of friends in high school. Somehow, I got the notion that I would screen the film Woodstock for my birthday. This was back before videos were available, but I learned I could rent the actual film (which came in several reels) and a projector from a local company that rented educational films to schools.

Some friends and I hung a white sheet across a wall in the large living room at 736 and then watched in amazement as an overflowing crowd showed up. The living room became a sea of teens from all over town crowded wall-to-wall throughout the two-story house. It was like any teen party scene held at a teen’s home, except in this case the parents weren’t merely away; they were never coming back. That cold night in February, we—the youngest of the Woodstock generation—partied like it was 1974.

Dean “Andy” Mathis, hunting in Oklahoma, mid-1970s. Dean was my best friend my freshman and sophomore year of high school. He and his family were like my own before and after my father’s death.

Me and René, Dean’s sister and my best friend since seventh grade. This photo was taken in their home in Seattle in 1973, when they brought me down for Christmas. René and I remain close.

Despite a huge group of teens doing what teens did at parties like this—play music really loud and drink alcohol—the cops never showed up. That was probably because the house sat in an area partially zoned for commercial development: Al’s Body Shop was across the street, the Tesoro gas station where I worked was next door, and Mark’s Drive-In was on the corner. There were no neighbors to disturb, no neighbors to watch us—or watch out for me.

CLEARLY, AT SOME POINT, I needed rescuing. Eventually, the cavalry showed up.

One day late in the school year, I was called from class into the counseling office to find a beautiful woman with stylish blonde hair dressed in a fur coat and in no way looking like what she was—a state social worker.

Her name was Michael Giesler and she saved my life that day. She told me my seventeen-year-old stepmother had called their office, saying I was a delinquent. Considering the source, they knew that might not be true, but they did realize at last that no one knew what was happening to this sixteen-year-old orphan.

It wasn’t long before I had a court-appointed guardian to help with legal affairs, medical and dental care through the State of Alaska, and a clothing allowance. I was assigned to live at the homes of friends of my choosing.

Aside from the social stigma of my dad’s businesses and death, I must have been a pretty good teen. Or they didn’t know better. A friend once noted that I was the perfect houseguest: I always picked up after myself, dove in with cleaning, left any room better than I found it. She surmised I learned that after being a guest in so many homes.

I don’t think she meant that was a good thing.

I had little oversight, I guess, because unlike many teens in state custody, I didn’t get in trouble. I was easy to manage. Beginning the spring of 1974, I had several families whose homes were opened to me, then and forever after: Floyd and Hazel Johnson, Marianne “Mike” and Earl “Red” Dodge, and Rod and Donella Bain.

It wasn’t as if things were quiet at their homes. The Dodge and the Johnson families each had six children; the Bains had four. They were solid homes where the dads worked outside the home and the moms were housewives. But the women were, then and now, role models to me. All were smart and adventurous for the times. Hazel Johnson was a World War II army vet (rare for women back then), a member of the League of Woman Voters, and a community volunteer who read voraciously. Mike Dodge had a bachelor’s degree in physics that saw its expression in her oldest son’s graduation from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Donella Bain was a kind and articulate person who didn’t seem concerned when her daughter brought me home one day to stay with them.

Earl “Red” and Marianne “Mike” Dodge. They took me in as a teen despite having six kids of their own.

Donella and Rod Bain, who helped care and house me after my father’s death.

Rod Bain was a school teacher and World War II hero, having been a sergeant in Easy Company—the “Band of Brothers” (part of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division) made famous in historian Stephen E. Ambrose’s 1993 book and the celebrated miniseries.

Floyd Johnson was a forester who had traveled with his family to Iran at one point for his work on reforestation. Red Dodge was then a captain with Western Airlines. Both these men were also World War II vets, and Dodge had flown dangerous bombing missions in the Pacific.

In addition, the state-appointed guardian was on hand to watch over my “business affairs.” He was a friend of a friend, a divorced father of two young children, and one of the most protective and important friends in this period of my life. Walt Morgan came from a longtime Anchorage family. He was an entrepreneur: he ran a bike shop, a janitorial service, a landscaping business, a commercial house painting business, and more. Throughout my teen and college years, I could always find work with Walt and later, whenever I needed it, a home and place to stay.

But more than anything, Walt was a devoted father, sharing custody of his two children with their mother. Some of my first lessons in good parenting came from watching Walt with his son and daughter.

Walt is one of the funniest people I know and a prankster who was always setting up elaborate jokes. When he sold his janitorial business, part of the deal said that he got the buyer’s luxury black sedan. As I walked downtown one night, the black sedan pulled up alongside me, the side windows came down, and as if it were a Mob hit, I was pummeled with snowballs.

Walt Morgan, my court-appointed guardian ad litem and friend who helped take care of me for years.

The Bains, Johnsons, Dodges, and Morgans became my foundation. I couldn’t have asked for better homes. No matter how many times I came and went, their doors remained open.

Maybe this, more than anything else, helped me grow up more or less the way I longed for—normal.

ONE RESULT OF THE Woodstock party was my introduction to a new group of people. I attended East High, but students from all across Anchorage showed up. One contingent was a group of shaggy-haired, casually dressed kids. They were into the outdoors, hiking, and crosscountry skiing. Their parents listened to folk music and the Beatles, were professionals and even politicians.

I felt instantly at home with this group. I was fond of my friends from East High, but with the death of my dad, I wasn’t drawn to the normal football game/prom/student government way of life. These new friends would take me in a different direction.

Not long after the Woodstock party, Bridget reappeared. I was living with the Johnsons when she called and announced that she had sold everything in my father’s house. Walt Morgan and I drove over to Twelfth Street, packed up my belongings, and left. I never saw Bridget after that, and I never again had to deal with the 736 Club.

It was a relief.