Читать книгу A Normal Life - Kim Rich - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

The “Hey, Wow, Man” School

I arrived home in the early spring of 1975. I had swapped Arizona’s sun and heat for Alaska’s gray skies and breakup, when winter’s snowfall turns to slush and mud.

I felt disoriented at first; picking up and leaving Phoenix wasn’t easy. Back in Anchorage, I had to find a place to live. I had no car—heck, I didn’t even know how to drive. I bounced between staying with my guardian, with a friend’s parents, and with a group of young people in Mountain View, one of Anchorage’s poorer neighborhoods.

The group house seemed like a good idea at first. My friends were all staying together in a broken-down house that was more or less a shack. A couple of the guys living there were in a garage band. They set up their instruments in the living room, where they practiced and played for nearly nightly parties.

The place was small, crowded, and dirty. I hated living there and soon began to become disenchanted with hippies—although it would take a few more years before I abandoned the concept altogether.

Eventually I settled into living with the Dodges or the Johnsons. That fall, I enrolled in Steller Secondary School, Anchorage’s alternative public school. Years later, I would refer to Steller as the “Hey, Wow, Man” school. Even so, it wasn’t quite as hippie-ish as the so-called Free School some teens had created in Anchorage, where it seemed all they did was drive around together in an old van. Steller was named after eighteenth-century German scientist and explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller, who had extensively mapped Alaska’s flora and fauna.

Steller was founded by civic-minded parents and veteran educators who wanted something different—a place where students learned to love learning. The school philosophy emphasized self-learning. Steller was right in line with an educational movement occurring across the country. Parents disenchanted with a traditional education worked to create schools that mirrored the youth-oriented counterculture that had begun a decade earlier. They viewed informal education—or, as they came to call it, “open education”—as an answer to both the American education system’s critics and the problems of society. The focus on students learning by doing resonated with those who believed that America’s formal, teacher-led classrooms were crushing students’ creativity.

At Steller, that meant calling teachers by their first names, forming a student-led government to deal with discipline issues, and letting teachers create any classroom environment they wanted as long as the state-mandated curriculum was covered. Students could come and go from classrooms without hall passes.

The more relaxed atmosphere seemed perfect for me. It was at Steller that I learned to love learning. I constantly discovered new fields of interest and new paths of knowledge to follow.

As much as we really learned, sometimes independent study courses got approval when they probably shouldn’t have. For one such independent study program, a girlfriend and I tried to teach ourselves “ground school” in order to learn to fly. Ground school. Two teenagers teaching themselves ground school. This was somehow approved.

My friend and I would meet in the hall, sitting on the floor together, trying to read aloud a textbook on aerodynamics. We used our hands to demonstrate the principles of airflow, air pressure, and lift around an aircraft’s wings. It got so hard and so boring that it was all we could do to keep from falling asleep. After a session or two, we dropped the class for something else.

ABOUT 150 MIDDLE and high school students attended Steller. Many came from Anchorage’s upper-income homes or families with long histories. They were the sons and daughters of politicians, community leaders, and otherwise civic-minded families.

“We had a school uniform,” a friend from Steller quipped. Just about everyone wore hiking boots, belted jeans or corduroy pants, and waffle Henleys or flannel shirts. Back then some students, mostly males, carried buck knives; I used to joke that they were prepared should a wayward moose enter the building during hunting season. Actually, we weren’t hunters, or even Eagle Scouts or Girl Scouts ready for a campout. I suppose the knives were for popping open a beer at high school parties.

I took philosophy, music, art, and US government. Once standard high school core classes were covered, students could propose their own course of study. For my government class, my classmate Sigrid and I decided to pursue a project that would explore which agencies owned or managed Alaska’s lands. Whoever owned these lands—the federal government, the state, Alaska Native groups, or private owners—was and still is a hot topic in Alaska. Alaska did not achieve statehood until 1959, and when I was in high school, the state was still selecting the lands it was granted through the Statehood Act. Sigrid and I went around interviewing the heads of state parks, those who oversaw federal lands, and directors at the Bureau of Land Management. It was an important topic to us, since most of my classmates were outdoorsy. At Steller, I discovered a life of mountain climbing, cross-country skiing, and all-night bonfires.

My class of 1976 was the school’s second graduating class. We had about twenty students. We were, without a doubt, the Dazed and Confused generation, like the kids in Richard Linklater’s film set on the closing day of the 1976 school year.

We had nothing in common with the Baby Boomer generation that immediately followed World War II. We didn’t participate in the rebellion of the 1960s; we didn’t march against the Vietnam War; none of my male peers faced being drafted to go to war. By the time we graduated, the Vietnam War was over.

Our cultural rallying cry didn’t come so much against anything but more for something. That something became being outdoors in every fashion and form we could think of: hiking, cross-country skiing, mountain climbing, or getting on the water—usually freezing cold water.

LOOKING BACK, I see many ways I might have died exploring Alaska’s vast wilderness. I knew some people who did. Somehow, my friends and I survived, although given some of the risks we took, we were lucky.

One overnight winter camping trip set a group of us—about three or four guys and two girls—on an overnight trip that involved crosscountry skiing to Whittier, a small coastal community on the other side of the Chugach Mountains to the east and south of Anchorage.

About sixty miles from the city of Anchorage, Whittier sits on a canal off Prince William Sound. The only land access is via the Alaska Railroad, through a nearly two-and-a-half-mile tunnel.

One of the guys in our group was in a full leg cast.

Our plan involved getting dropped off at Portage Glacier, a popular tourist destination on the highway about two miles away from the tunnel.

Allow me to repeat myself: it was a train tunnel. As in, only a train. In a tunnel. Not a pedestrian walkway, not a road, not a known or encouraged route. It was illegal to walk through the tunnel unless you were an employee of the railroad.

I’m also sure that during the winter months, the train did not keep a regular schedule going in and out of Whittier. In other words, we had no idea if or when a train would come through while we were in the tunnel.

Our trip began well, with an easy ski to the tunnel entrance. Once there, we took off our skis and opened a door meant only for railroad employees. Inside it was pitch black. No lights. We all had flashlights or headlamps, and it was these that guided us down the tracks, with our skis and poles slung over our shoulders.

The walking was perilous. Here and there mounds of ice had formed on the dark tracks where water dripped inside the tunnel.

I don’t remember if I had been in on the planning of this trip or if others had meticulously planned the excursion. All I know is that I blindly went along. Once inside the train tunnel, I was terrified that a train might come along.

As I walked, I looked to either side of the track, trying to gauge if there was room for us to stand against the wall and not be hit by the sides of a train. It didn’t look like it. In my mind, I practiced splaying my body against the wall, making myself as flat as I could, hoping not to be dragged off.

Fortunately for us, no train came that day, and we reached the other side safely. But our troubles had just begun.

The wind was so strong when we left the tunnel that it knocked us over like matchsticks. We retreated back inside to figure out what to do. The original plan had been for us to ski into Whittier and find a place to camp. But the town was several miles down the tracks, and every time we tried to step outside and put on our skis, the wind would knock us down.

We decided to trek to the side of the tunnel to find a spot to build a snow cave and camp. Leaving our skis and poles in the tunnel, we stumbled along the lower slopes of the mountain, trudging like mountaineers on Everest: Step. Stop. Brace. Step. Stop. Brace.

What we had not prepared for was how deep the snow was around Whittier, which receives an average of nearly 270 inches of snow a year. It snows so much there that walls of snow regularly cover the first-story windows of homes.

Eventually we came to a jagged tree that offered a slim buffer to the winds. There, we set up camp. We didn’t have tents, so we dug out under and around the tree and covered the whole contraption with a piece of plastic sheeting.

The Ritz, it was not.

We did have a small propane stove to heat food and drink though. Once inside our makeshift shelter, we were warm enough to take off wet outer layers and hang them on a string tied across the top of the shelter and relax in our long underwear. Our space roomed three comfortably. Maybe four. But five of us? We somehow managed to crisscross our sleeping bags and eventually go to sleep.

The next morning, after thawing clothing that froze on the clothesline overnight, we broke camp and decided to try to get into town again. One of our party, the guy in the leg cast—the least likely to get ahead—struck out on his own. By the time we got to the tunnel to retrieve our skis, he was long gone.

Some of us tried to ski along the snow-covered tracks. Every few feet, the wind would knock us down. Eventually, we took shelter in a small, abandoned wooden building.

There, I cried. My fingers and feet were frozen and hurt. After resting a few minutes, we decided to go back to the tunnel and regroup. Once there, we warmed up. God only knows what we thought we were going to do next.

Then, deep inside the tunnel, we saw a tiny, bright light. As we stared at it, it got bigger and closer. Something was coming down the tracks. Fortunately, it wasn’t big enough to be a train.

Like a knight in shining armor upon a white horse, a railroad worker riding a white Polaris snow machine pulled up to us and stopped. He was a young and friendly guy who might have encountered people like us before. He told us to stay put. He went into town, and a short while later, he pulled up outside in a pickup truck.

We loaded our skis and our shivering selves into the back, and he drove us into Whittier. Our rescuer took us to his house, where we camped on his living room floor. Later that night we reunited with our friend in the cast, who had successfully skied all the way into town.

When it was time to go home to Anchorage a day later, we bought tickets on the train.

THAT WAS MY LAST winter camping trip, but not my last attempt at wilderness camping.

One summer in high school, I went with two friends (including one who had been on the ill-advised ski-through-the-tunnel fiasco) to Denali National Park. The park is home to Mount Denali, the tallest mountain in North America at 20,320 feet.

Sigrid, Kim, and I got to the park and picked up our backcountry permit. It would allow us to leave the only road through the nearly ten-thousand-square-mile park and designated wilderness area. That road is ninety-two miles long.

Aside from a fall lottery that allows some lucky motorists to get a pass to drive into the park, most of it is strictly off limits to motorized vehicles of any kind. A yellow school bus, then and now, takes tourists on a long, slow ride through the park all the way to Wonder Lake.

The bus dropped us off at our designated camping area. To assure no disruption of the wildlife in the area—wolves, grizzly bears, and dozens of other types of animals—only so many backcountry passes are issued at any given time.

We felt lucky to get ours the moment we stepped off the bus. Shaggy tundra and bright wildflowers and rippling streams unrolled before us. The mountains we had traveled through on our way to the park suddenly looked like foothills beside massive Denali. There is no view like it on earth.

Our drop-off point was on a high ridge with a gentle slope that went down to a braided river. Carrying heavy backpacks, we easily descended the slope to the bottom of the river valley that runs through the park. We wore our hiking boots but had nothing waterproof for wading through the shallower parts of the river.

We walked up and down, leaping from sandbar to sandbar, as we made our way across. But at one point, there were no more areas we could jump over. We would have to wade across what seemed to be a nonthreatening and slow-flowing branch of the river.

We discussed our options: get our boots and clothes wet or go barefoot and, well, in our underwear. We hadn’t brought shorts of any kind, nor perhaps a dry change of pants.

With summer evening temperatures on the cool side, we opted to keep our clothing dry. We stripped off our boots and pants, threw them in our packs, and began to wade through the water.

I discovered, as anyone who has ever crossed rivers and streams in Alaska in summer knows, that the water was freezing cold. Bitterly cold. Painfully cold, as if you are being stabbed with a thousand knives. You feel you can’t breathe. You just might die.

Or, in our case, die of embarrassment. As we began our crossing, we turned to see that another park bus was stopped on the road high above us. The bus drivers usually stop to allow tourists to photograph wildlife. Using our binoculars, the three of us realized that the tourists all seemed to be looking in our direction.

We looked around. Could there be something nearby? A moose? A bear?

Nope.

We realized the tourists were looking at three teenage girls in their underwear crossing a small stream of water that turned out to be no higher than our knees.

Oh well, we figured. Not much we could do about it anyway, and besides, it was unlikely there was anybody on that bus who knew who we were. Once on the other side of the stream, we dressed and continued on our way.

We spotted a small hill where we decided to camp. As we approached, we saw something even more alarming than our earlier misadventure. A sign read: PRIME GRIZZLY BEAR RESTRICTED AREA. Or habitat. Or whatnot. The message was clear: our backcountry permit area was right next door to GRIZZLY BEAR HABITAT RESTRICTED AREA.

We knew this meant employing all the bear-deterrent camping rules we had learned from one of the park rangers. We had to prepare, eat, and store our food far from our tent and sleeping area. Somehow, we got the idea that we should also bury our food containers and eating utensils deep in the ground. (We thought this was safe. It didn’t seem to occur to us that bears have great noses and big claws for digging.) For extra measure, we decided to leave the clothes we wore that day with the buried food, which meant changing outside. For those who aren’t familiar with this kind of terrain, there are few to no trees.

We would have felt clever and prepared had we not forgotten two critical things: matches and, most important, mosquito repellant. The former meant we didn’t eat any cooked food that evening. The latter meant that we had to swat mosquitos madly while eating and burying and running to get inside the tent, followed by zipping up the door quickly and then frantically slapping and killing as many mosquitos as we could.

Aside from such moments, our camping spot was perfect. As with all of Denali National Park, the vistas are huge and the landscape epic, like one of those nineteenth-century wall-size paintings of the American West.

That night, as we settled into our sleeping bags, we devised our own bear-deterrent plan. If any of us awoke in the night, we were to peer outside and either yell “Bear!” if we saw one or yell anyway to scare anything in the near vicinity.

We all slept fitfully that night, being near the grizzly bear habitat restricted area. At one point in the middle of the night, I dreamed not of a bear but of a large spider, slowly descending from the top of our tent. I leaped up and slammed my hand down to kill it, yelling loudly.

Immediately, Kim popped up and cried, “Bear!” Then she lay back down and kept sleeping. Sigrid and I, now both awake, just looked at each other. Then we closed our eyes and also went back to sleep, or something like sleep, under the Alaska summer night sky that never gets dark. We hoped the bears next door would stay put.

IN THE SPRING of 1976, I graduated high school. At Steller, we made our own graduation gowns in the style of wizards’ robes, with hoods and long trumpet sleeves. They were made of beige or white cotton or gauze. We decorated our robes in everything from batik to applique. I tie-dyed mine.

About twenty students were in my class that year. Our graduation was held in the gym/cafeteria at Steller. I think we all spoke a few words; I remember saying only, “No more homework!”

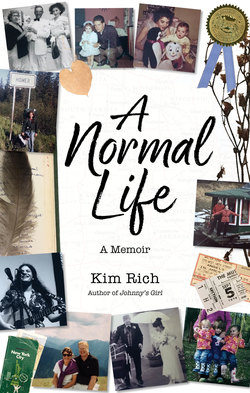

My graduating class at Stellar Alternative School. (Photo courtesy of Alaska Dispatch News)

A photo of our graduating class, of young men and women in long, flowing hair and long, flowing robes, has always reminded me of a painting of Jesus’s apostles.

That, of course, may have been the point. We eschewed all things that were part of conventional and traditional high school life—sports, homecoming, and prom. The girls didn’t wear makeup, and the guys didn’t get haircuts and, in some cases, didn’t shave. I look at photos of me from this period of my life, my hair down to my waist, and think, Would someone please give that girl some hair care products?!

In a way, we were like the apostles that spring, minus a leader. Our figurehead was the entire state of Alaska and the outdoors.

The only time I ever engaged in vandalism was after a night of high school partying. A group of us drove out to South Anchorage, to the site of the first-ever overpass/on-/off-ramp constructed along the only highway south of town.

We sneered at this latest development. On the green sign next to the northbound on-ramp, one of our group jumped out and spray painted the word “Los” above the official “Anchorage.”

Los Anchorage, as in Los Angeles. One meager on-/off-ramp. Is there a statute of limitations on misdemeanors?

THIS WAS ALSO the era of garage rock bands and the worship of rock band musicians, and I was not immune. If a guy played guitar, had long hair, and even vaguely resembled, say, George Harrison, I was smitten.

For a while, about the time I graduated high school, I had a boyfriend who played bass. The more hippie-ish of my friends and I would go to hear bands in our standard rock concert outfit—long cotton skirts, hiking boots, and peasant blouses.

During those days I met two brothers who had come to Alaska from Rhode Island. One of them dubbed me and my friends “little pioneer women.” He once tried to describe what it was like coming to Alaska from the East Coast. At home, his idea of wilderness was the view from a hill above a freeway with nothing but forests or fields as far as the eye could see. But Alaska’s wilderness was almost beyond comprehension.

I wasn’t sure I understood, but the summer after I graduated high school, I decided to hit the road again to explore the rest of the world.

My bass-playing boyfriend wanted to go to Jamaica because of the growing popularity of Bob Marley and reggae music. I had no such desire. I was willing to go as far as Rhode Island, where I had friends.

We rode the state ferries through Southeast Alaska, flew, hitchhiked, and took buses. From the Pacific Northwest, we went across Wyoming, then into Nebraska, where I still remember the most generous people who opened their homes to us for overnight visits. Iowa was where I began asking, “Is this the Great Plains? Is this?”

At one point, we stopped for lunch at a Howard Johnson’s. I picked up something off the table—a condiment, perhaps—and was amazed that it had been manufactured right there, in the town we were passing through. In Alaska, nearly everything comes from somewhere else.

Along the way we reached a small farming town and stopped in a café. The place was filled with regulars—farmers and retirees, old men dressed in coveralls. I felt all eyes on us hippies. I was a little intimidated but more enthralled by what seemed like the all-American scene of middle America.

Later, we hitchhiked amid tall cornfields. A family in a station wagon picked us up—a mom, dad, son, and daughter. I can’t recall their names or where they were going, but I was floored by their courage and openness. They were friendly and talkative and kind. I can’t imagine anything like this happening today, but in the summer of 1976, it was still possible.

We met a lone female college student who drove us most of the way through the rest of Iowa before we turned north through Minnesota and headed toward my mother’s hometown of Ironwood on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

I ENTERED IRONWOOD with great trepidation. The three years I had spent there between the ages of six and nine were painful at best. My parents had split up, and my mother would spend her few remaining years in and out of mental institutions. But like any place you go back to as an adult, all things that once seemed enormous feel somehow small with time. So, too, were my difficult memories.

I was happy to see my mother’s family and felt a sense of belonging, of my roots. I found that my memories of life with my Italian grandmother, once alienating and harsh, were now engaging and quaint. The hill by her house that had been such a long climb was nothing to an eighteen-year-old.

I looked up what childhood friends remained, or their parents. I was struck with how much I liked the place and the people.

I remembered that when I was a little girl in Ironwood, there was one family that had a son, Bobby, who was older than me. My memories of him were not good. He would bully me again and again. He liked to trick me into getting on the bench swings of the old metal swing sets. He’d swing the entire thing so hard and high that it seemed the entire swing set would topple over. I would scream and cry in fear.

Bobby was the boy who wouldn’t let me take refuge in his house as a thunderstorm approached one day. In Ironwood, you could see storms approaching on the horizon, all dark, low clouds and menace. I hated thunderstorms and was always fearful my grandmother’s house would be struck by lightning.

That day at Bobby’s, he had given me no choice but to run all out for my grandmother’s house across a large field. I may never forget that day, out in the open in a full-on thunderstorm, getting soaked in the downpour. Terrified.

Now that I was all grown up, I looked forward to confronting that little SOB Bobby.

Bobby’s mom was named Stella. She, like the rest of the families that lived in Jessieville just outside Ironwood, had been a friend to my mom and to me.

When I arrived, Stella and Bobby’s younger brother greeted me warmly. Then we waited for Bobby to arrive.

“Bobby loved you so much,” Stella said. “He still talks about you and always wondered what happened to you.”

Huh? Are we talking about the same Bobby here? I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Should I tell her what he had done to me? What my memories were?

I decided against it. Then Bobby walked in the door. He practically had tears in his eyes when we hugged. He was handsome, polite, and soft-spoken.

I don’t know if I ever told him of my memories of growing up with him. I might have been too shocked to think of what to say. What would be the use of dragging up bad memories? I just let it go.

During that trip, I visited my mother’s gravesite for the first time. She was buried in a downtown plot with her parents, my grandparents Marietta and Paulo Chiaravalle. I suppose that was the right place for her, and I took some comfort in that. But her headstone gave Chiaravalle as her last name, with no mention of Rich.

I thought that someday I would go back and buy a new headstone and include her married name. I have yet to do that.

AFTER MICHIGAN, I headed east to Rhode Island to meet up with the friends I had met in Alaska. My bass-playing boyfriend and I had parted ways, so I continued on alone.

In Rhode Island, I experienced another first. My friend and I took a day trip to Block Island, a popular vacation area. At one point, I stood in the surf for a photo. My friend yelled at me to turn around, and just as I did, I was overcome by a wave of water. For the first time ever, I tasted saltwater.

I had made my way across the entire continent. It was time to go home.

THAT FALL, MANY of my classmates from Steller headed for Ivy League or other storied private colleges in New England. Others chose schools that specialized in arts and crafts, or unique trade school programs, such as a wooden-boat-building school in England.

Initially, I wanted something akin to my experience at Steller, so I found an alternative music program at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington. However, my life took another turn.

Someone wrangled me into volunteering at the State Democratic Party headquarters.

It was 1976, the bicentennial of the nation’s birth. Jimmy Carter was running for the presidency. Young people were energized by his campaign. I’d been accepted to college, but I deferred my admission as I got swept up in my first and last foray into politics. What I got for my volunteer time was the promise of a job in Juneau as a page in the Alaska House of Representatives.

After Carter’s win in November of that year, I packed my bags and moved to Juneau with little money and little idea just how hard such a move would be.

It was the middle of winter. I arrived in a small town that was cut off from the rest of the world except by plane or boat.

I have needed knee-high rubber boots two times in my adult life: in Juneau and in New York City. Both have bitter rain and snow storms. Of all the places I have been, both have the most expensive housing, and people are willing to live in the most God-awful places. And despite the massive size difference between the two—Juneau had about twenty-five thousand residents in the late 1970s, and New York City over seventy million—both seemed to be the center of the universe.