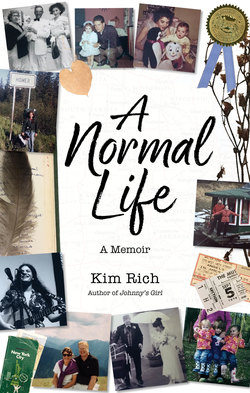

Читать книгу A Normal Life - Kim Rich - Страница 8

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Peaceful, Easy Feeling

By summer 1974, at just sixteen, I was ready to leave Alaska and go see America. My destination: Phoenix, Arizona.

I picked Arizona because of a new friend named David Ray.

David was in Anchorage for a brief stay before flying to Phoenix, after working a season at a remote Alaska fish processing plant. A mutual friend introduced us because David needed a place to stay and there was room at my house.

A few years older than me, David took to me like a big brother. Of average build, David had long brown hair he wore down or in a ponytail, was soft-spoken and easygoing, and spoke warmly of his hometown and the American Southwest.

David had heard me talk so much about my dream of going to the Lower 48 that one evening he pulled me aside. He talked about his parents and an older sister and her family who all lived in Phoenix. He said I’d have a place to stay, and more than that—a home with him and his family.

He then did something I’ve never forgotten—he pulled out a $100 bill.

I was floored. That was a huge amount of money to a teen at the time.

“This is to help you get down there,” he said.

I promptly put the money in my bank account and used it later to help pay for my trip.

I WAS ALSO DRAWN TO ARIZONA and the desert by the fact that nearly all of my favorite bands or singers had songs about the area. I wanted to stand on a corner in Winslow, Arizona, as singer/songwriter Jackson Browne had written.

My plan was to hitchhike down the West Coast with a friend named Greg, the older brother of my eighth-grade boyfriend, who had moved to the San Francisco Bay Area with his mom a couple of years earlier.

Greg was going to see his family. Our itinerary called for flying to Seattle then going from there.

We had a big send-off the night we were to catch our red-eye flight. In the handful of grainy-looking color photographs that still exist, we’re with the dozen or more friends who showed up to say goodbye. We all looked like hippies, with flowing hair, flannel shirts, blue jeans, and hiking boots.

We all posed for one photo; others show Greg and me preparing to walk down the jetway to board our plane. In still another, I am alone on a padded vinyl bench, writing in my journal. I do not look happy. Perhaps whoever took the photo interrupted my writing, or maybe I had already had the first of many fights with Greg.

Our plan was to fly to Seattle then hitchhike to San Jose, California, where Greg was headed to join his brother and mom. On the way, we stayed at a youth hostel in Eugene, Oregon, where I visited a friend at college.

That first trip emphasized the distance I felt between my Alaska home and the rest of America. Years later, my film director friend John Kent Harrison, a Canadian by birth, quoted a fellow Canadian about growing up above the contiguous forty-eight states: “It was like living in the attic of a house having a party.” And boy, what a party. Everything about America fascinated me, and it still does.

Anchorage International Airport, Summer 1974. While waiting to catch a red-eye to Seattle, I took some time out to scribble in the journal I kept at the time.

Greg and I turn around for one last shot before boarding our flight.

That trip introduced me to the vast natural beauty of California, a state I have seen more of than Alaska, in part because most of Alaska is not accessible by road. Over the years, I’ve driven the coast highway from Oregon to Los Angeles, and I’ve driven straight through the middle on I-5. I’ve spent time in Northern California, in the redwoods around Mount Shasta. I’ve driven to Lake Tahoe, visited a friend’s farm in the mountains around Ukiah, gone to the wine country, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, Santa Cruz, Pismo Beach, Santa Barbara, and so on. Sometimes, it all blurs together.

But I have distinct memories of that first trip, including our first night in Northern California. We made it to Redding and got a hotel room. After settling in, I turned on the late-night TV news. The weather announcer reported the temperature was one hundred degrees.

One. Hundred. Degrees. At midnight.

I ran outside and looked up at the stars. Never before had I experienced one hundred degrees. At midnight. I loved it.

I’ve long joked that my bones are made of permafrost, the part of the Arctic ground that never completely thaws. In Alaska, if it’s dark, it’s always cold. If it’s warm, it’s always light. To be warm—even hot—in the middle of the night was an entirely new sensation to me.

Days later, at a party with my old boyfriend and his friends in San Jose, I stepped outside again to take in the night heat. As I stood there, I could hear Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” blasting from inside. In the mid-1970s, that song got played late in the night at every party.

I was an Alaska-raised girl standing in California, where I was born, listening to a rock band from Alabama. The moment was not lost on me. It was one of my first lessons in the power of music as a unifying experience.

Later that trip, Greg and I spent a long, hot day hitchhiking to Santa Cruz to go to the boardwalk and ride the Giant Dipper, the wooden roller coaster. That was all we talked about on the way, but once there, I looked up at the rumbling monster and declared “no way” was I getting on. I repeated this all through the long line, right up until I managed to make myself step aboard.

What happened became a life lesson: I loved it. I loved it so much that when the ride ended, I asked if I could go again.

Ever since, whenever I find myself balking at something—any new adventure, project, or life transition—I tell myself it’s like standing in line at the Giant Dipper. It’s all fear and anxiety and caution, and then you just do it.

AS PLANNED, Greg stayed behind in California and I took a bus the rest of the way to Phoenix.

From the moment I arrived in Arizona by bus from California, I was hooked. I loved the hot desert climate. I would bask, if only momentarily, in the end of summer’s excessive heat. In October, a friend called from Anchorage to describe the winter snow and cold. I was still wearing shorts, and it was seventy-plus degrees.

One of the few downsides of the desert was scorpions. I learned to hate them after staying with friends at an old farmhouse on the outskirts of Phoenix. When I arrived and was shown to my room, I noted something odd about the twin bed.

“Why are the legs sitting in glass jars?” I asked.

“So the scorpions can’t climb up into the bed,” my host said.

I dreamed of giant scorpions every night after that. I slept fitfully, clutching my bedcovers in the fear that they would fall to the ground and the scorpions would find their way up to me.

Soon, I had plenty of other things to distract me. Arizona was the center for much of the New Age/hippie/Eastern mysticism/Eastern religious thinking seeping into American popular culture. In the mid-Seventies, Arizona offered new ideas about everything from what to wear to what to eat, believe, and read.

In just a few months, I was wearing all white: long gauze skirts, white peasant tops, and sandals, almost like a yogi. I tried fasting for days on only apples. I’d never been so miserable, and it was years before I could eat apples again.

I began practicing yoga with Lilias, Yoga and You, a TV show on PBS hosted by Lilias Folan. My friends and I hiked in the mountains surrounding Phoenix at night, under a full moon.

It was a time when hippie men began apprenticing in the silver and turquoise jewelry trade as the state’s many large and small turquoise mines experienced a boom. I came to appreciate the different kinds of turquoise and Native American culture and arts and crafts. I learned to enjoy desert ecology and nature. I found those in Arizona had the same affinity for wild places that my little hippie-ish (at least in dress) friends and I did in Alaska.

Throughout the remainder of my teens, I traveled between Arizona and Alaska. I slowly developed a style of dress and an attitude that said “hippie.” Inside, though, I was still very much your all-American teenager.

My friends and I talked about living on a commune, where we would bake our own bread, make our own pottery and dishes, grow our own food, and milk our own cows. In addition to being essentially a calling for all hippies from that era, to a city kid like me who had never lived a rural lifestyle, this seemed a romantic notion.

When I say “all-American teenager,” I mean I didn’t fall for the hippie belief in free love. I now like to joke that such a thing was only an excuse for ugly guys to get girls to sleep with them. I still believed in saving myself for that special someone.

I once watched in horror at a party when suddenly someone announced “orgy time,” and a bunch of young men and women began taking off their clothes and running around the house naked. I left.

I believed in what other young teens believed in: love, rainbows, and maybe unicorns. In Arizona, that didn’t change. It wasn’t as if guys were beating down the door to ask me out. I considered myself attractive, but I was never that interested in male attention. I was pretty smart and terrified of the opposite sex. While I had lots of crushes, none went anywhere.

I think my hesitation stemmed from having a father who sold sex. I grew up around women who were victims of the sex trade and nude-dancing business. Although some of them were intelligent and quite nice, and a rare few were college graduates, I knew that most were trapped in a life they hadn’t chosen. That wasn’t going to happen to me.

I found the hippies and the idea of getting back to nature appealing. It was a trend, but given what I grew up with at home, it made sense. It was my rebellion against my father’s lifestyle and the exploitation at the 736 Club. In Arizona, I experienced a personal renaissance. I also discovered Be Here Now, the 1971 book on spirituality and meditation by Western-born yogi and Harvard professor Ram Dass.

PHOENIX WAS ALSO the largest city I had ever lived in (aside from Los Angeles when I was an infant). Every major rock or popular music act came through. To a teenager who practically worshipped contemporary music, Phoenix was heaven.

I got a copy of the concert schedule for one of Phoenix’s landmark venues, the Celebrity Theatre, a round theater with a revolving stage and intimate setting. Everybody I listened to on the radio seemed to be coming through Phoenix the winter of 1974–75. I decided to stay.

As my original Arizona contact, David, had promised, I found a home in Phoenix. David’s older sister had invited me to stay with her, her husband, and their young son. They lived in a small apartment that had only one bedroom, and yet they put me up on their couch that fall.

When that arrangement got to be too much for all of us, I met a beautiful high school sophomore who decided I was to be the sister she never had. In keeping with the times, Donna had changed her name to her chosen yoga name, Anandha Moon. I met her at a George Harrison concert in Tucson, where David took her for their first date. I was dumbstruck when I first saw her—lithe, with hip-length straight brown hair and large almond-shaped eyes, wearing a button-down 1940s-style jacket and long skirt. She was the most beautiful girl I had ever seen.

As if the meeting and the concert weren’t enough, that night my two companions and I camped overnight outside Tucson. I had no idea where we were going. We arrived at a campsite way after dark. Somehow, we managed to pitch our tent, unroll our sleeping bags, and fall asleep.

In the morning, when I awoke and stepped outside, I was stunned to see that we were in the middle of Saguaro National Park. All around were towering saguaro cactuses standing like soldiers at attention.

It wasn’t long after that meeting that Anandha convinced her family to let me live with them. That fall, I enrolled in the neighboring Maryvale High School. Because I had arrived late, I had to wait a few weeks for the quarter to end before I could begin classes. I went to the school library every day because I was afraid I would fall behind. There, I read magazines, books, whatever caught my interest. And I wrote, one essay after another. I wrote and wrote.

Once in school, I was invited to join the school newspaper—probably because I was new and enthusiastic and one of my teachers who advised the paper liked my work in class. Before long, I was one of its main reporters and writers. I not only did news copy, I wrote poems and essays, including one love poem for the Valentine’s Day issue. Looking back, it’s pretty embarrassing to read; if nothing else, I had the passionate, overwrought heart of a teen girl.

There, at Maryvale High, with its handsome campus of interconnecting indoor and outdoor halls and walkways, I got to be a carefree teen again. There, I thrived. I developed a couple of crushes—one on a quiet, handsome boy named Buck, and another with curly, shoulder-length hair named Barry. The former I helped get a poem published in the newspaper while the latter talked about finding me “hot.” It was hardly the image of myself that I cultivated. I also became friends with the editing staff of the newspaper, and they invited me to their homes. To all at Maryvale High, I was just another teen—no one knew about my dad or what he had done for a living or what had happened to him. I felt free of that yoke, and an amazing thing happened: I earned straight A’s in every single class. My English teacher liked one of my essays so much that she even entered it in a state competition representing the school.

My Maryvale High School ID in Phoenix.

Many of my fellow students were bored in school. I was gung-ho simply because I had experienced the absence of school, which was far more boring. I learned then that showing up was everything; just doing the work and showing some enthusiasm impressed the teachers. From the student newspaper advisor to my ceramics teacher, I got nothing but encouragement, support, and a strong belief in myself, at least for a time. I excelled and I thrived.

To the delight of one devoted art teacher, I decided to build a tall rope urn in the shape of a fish. I found a photo of an ancient Egyptian clay work with the most gorgeous turquoise-blue glaze. I was determined that my fish vase be the same color. The teacher must have worked with me for weeks to recreate a color from the time of the pharaohs.

I discovered country rock music and Linda Ronstadt, and thus began a love of singing and the desire to sing professionally.

I began to sense that I would live a life in the arts, though I wasn’t sure exactly what I would be doing. Somewhere along the way, I even began to think I might end up living in a utopian society.

Anandha had friends who purchased a large chunk of land in central Arizona. Others, including Anandha, bought into what was simply called “The Land.” They held meetings to plan an eco-friendly lifestyle on the wild piece of property, hoping to build homes someday for themselves, their friends, and their families.

I would go with Anandha to The Land meetings. I’d walk home from school in my long, white gauze skirt and peasant blouse, savoring the sun and heat.

That alone was a stark contrast to the life I knew in Alaska.

I should have stayed in Phoenix. But I didn’t. Like any teen, I was impulsive. By the spring, I was homesick. I’m not sure how I got the money—possibly from my mother’s Social Security benefits that had been coming for me since her death—but one day, on a whim, I flew home to Alaska.

Anandha and her daughter Rhianna at The Land.