Читать книгу Poacher - Kimon de Greef - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

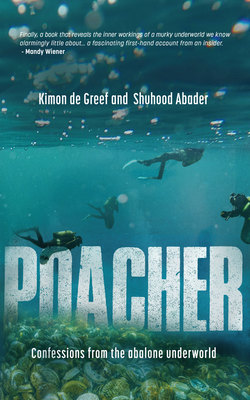

ОглавлениеShuhood Abader came to me with a book. He wanted help finishing it. For over fifteen years he had been an abalone poacher, lifting from reefs around South Africa a shellfish worth hundreds of dollars per kilogram in Asia. In prison he had begun writing about his life inside the trade—an entrenched criminal industry stretching from the Cape underworld to China’s luxury seafood market. After getting out, in 2008, he resumed poaching, but later sought to leave it behind. When I met him he was trying to get his manuscript published. Its title, he said, might be Confessions of a Poacher.

This is his account, augmented with my own reporting on the abalone black market. Along the way it is the story of a South African mollusc that became a marker of wealth halfway around the world.

A marine snail with a scooped shell, abalone is found on the coastlines of every continent except Antarctica. For more than 2 000 years it has been associated with status in China, first as a mainstay of royal banquets and more recently as an aspirational food for the middle class. One abalone species, found only in South Africa, developed a particular reputation for its size, flavour and value for money. It now faces commercial extinction—the point beyond which harvesting it will no longer be profitable for the legal industry—after more than two decades of relentless illegal fishing.

Many people are familiar with this poaching narrative: a legacy of outrageous decline, fuelled by greed and criminality. The creature known locally as ‘perlemoen’ and scientifically as Haliotis midae once smothered inshore reefs for hundreds of kilometres, in many areas packed edge to edge.1 Now traces of this abundance remain: small patches and scattered individuals that have escaped detection or are too dangerous to access. An item of natural heritage, adapted to South African conditions over millions of years, consumed locally since the time of the San, has been nearly wiped out.

It is divers like Shuhood who participated in this decline, crawling through kelp with metal levers to dislodge and eviscerate as many abalone as possible. The syndicates they supply have in the past 25 years smuggled out more than 50 000 tonnes of the shellfish, equivalent to some 130 million individual pieces. Reports of poaching appear in the news every month, blurring into each other. How and why the market for abalone operates, though—what drove its rise, what sustains it—remains largely absent from the public record.

Shuhood’s confessions throw light on this deeper story. Abalone has embedded as an underworld commodity and become a means for thousands of people to transcend conditions of poverty, if only fleetingly. Through the trade in abalone it is possible to read a social history of South Africa and the forces, often hidden, that govern life at its margins.

This is a book not about environmental degradation but about the circumstances, both past and present, that brought on the perlemoen’s demise.

*

Born into a family of artisans and professionals, Shuhood was cast among the children of Cape Town’s underclass by apartheid’s forced removals, hardening with them on the streets of a coloured township. He ran with small gangs and later violently opposed the merchants pushing drugs into his neighbourhood, becoming known for a reckless militancy. After being jailed for vigilantism, he was initiated into the 26s gang, entering the order of the Number that governs South African prisons. Upon getting out, like for many young men around him, a life of criminal enterprise beckoned.

But instead of embracing this path he tried to renounce it. The world of gangsterism was at odds with his beliefs as a Muslim. Still, he had young children to raise—eventually he would father seven—and a narrowing range of options. The choices he had made had incrementally constrained him, he felt, until by becoming a poacher he was locked in.

In pursuit of abalone Shuhood has been shot at, chased by car and by boat, blackmailed, robbed, and circled by sharks. He almost drowned on at least four occasions and once felt the thud of a fellow diver being struck by an outboard motor. To date at least seven men he worked with have died poaching abalone; dozens more have been arrested or developed drug problems. For years the threat of danger translated for Shuhood into adrenaline and a sense of brotherhood. These feelings later turned to resentment and fatigue.

Today he has little to show for his poaching life. With his second wife and their four young kids he rents a single room on the Cape Flats, a short distance from the streets of his youth. The kitchen measures three by two metres. It is crowded with the debris of a big family: school books, laundry, dishes, toys. An abalone shell serves as an ashtray. The children play in the yard or out front on the road, but no further, because the neighbourhood is not safe.

Shuhood’s writing began as a possible means of earning money, but spilled out into a wider reckoning that has not yet ended. ‘There’s a certain sadness that it’s come to an end,’ he told me. ‘And that anxiety now—how am I going to fill the gap? There isn’t something to replace it.’

*

My own journey into the poaching world had different origins. In 2012 I was studying a Conservation Biology masters at the University of Cape Town and needed a thesis topic. Serge Raemaekers, a researcher in the geography department, was hoping to profile the rise of abalone poaching in Hangberg, the fishing community above Hout Bay’s harbour. I saw an opportunity to step beyond what I knew, and said I would try. I spent the next seven months visiting Hangberg, meeting dozens of people involved in the trade. I had no investigative experience but came away with a lesson: behind every conservation story is a human one.

The work was disorientating. When I was a child, my family lived on the other side of Hout Bay, in a neighbourhood that was almost exclusively white. Hangberg lay within sight of our home, its grey flats and shanties rising against the Sentinel Mountain. I had only ever passed through, tense and self-conscious, to hike or watch big-wave surfing at Seal Island. There were few other reasons for people from my neighbourhood to go there; this is how spatial apartheid works. Returning for research opened a new point of entry, changing how I thought about the place I had grown up in. Becoming a journalist afterwards, I continued to write about poaching.

Like Shuhood, my life had changed course with abalone.

*

The abalone spends its adult life peeping out over a muscular foot. Its tiny face has eyes on yellow stalks and a puckered mouth with two tentacles. Pressed against a glass aquarium—like at the Chinese restaurants that sell live abalone in Cape Town, ostensibly farmed but often purchased from poachers—this mouth looks strangely expressive, as if it is gasping, or flung open in song. Because of its face the creature is easier to identify with than, say, a mussel, but this does not in the least bit trouble divers like Shuhood.

Inside the mouth is a rasped tongue called a radula. Up close the radula resembles a thin strip of sanding paper, equipped with neat rows of miniature teeth. The natural diet of the abalone consists of kelp and other seaweeds, which it methodically abrades with its tongue. The residue passes through its digestive tract, foul-smelling and bitter. ‘First thing you do after shucking a perlie,’ Shuhood said, making a quick movement with both hands, ‘is twist off the guts.’

The shell grows in a clockwise spiral, a row of ventilation holes perforating its leading edge. Its shape is described by the scientific name shared by all abalone species: Haliotis, Latin for ‘sea ear’. The outer surface is rutted and grey, the inside pearlescent and smooth. ‘Perlemoen,’ the Afrikaans name for abalone, is derived from the Dutch for ‘mother of pearl’.

There is an exquisite beauty to the shell, used since ancient times for jewellery, yet it is the flesh of the abalone, and chiefly its broad foot, that has made it so valuable. Prepared correctly, abalone is tender, with a delicate, buttery taste. This has drawn it into the crosshairs of human desire and produced a bizarre offshoot of global resource capitalism: a smuggling epidemic of snail feet, for displays of social rank.

*

It happened that Shuhood had joined the abalone trade in Hangberg, where I had studied it, and when we met it was possible for me to fact-check much of what he told me. We agreed that I would expand on what he had written, making me both his co-author and interrogator.

It has not been possible to verify every detail of his narrative, but in dozens of attempts I have not found a single discrepancy. (‘You’ve asked me that three times now,’ he once said to me, when I tried to winkle a sensitive bit of information. ‘I have to,’ I answered, and he laughed at me.)

His manuscript forms the spine of this book. Where possible I have quoted directly from his memoir, seeking to preserve his voice with only minor edits for clarity. I have distinguished between quotes from his book (with ‘he wrote’) and from interviews (with ‘he said,’ or similar). He has read and commented on every chapter. The royalties we will divide 50/50.

As equal partner of this project Shuhood has had greater agency than most subjects of nonfiction; this has been both challenging and an opportunity to explore a more participatory approach to storytelling. I have pushed him on aspects of his life that he did not want included, but that I felt were important. Some of these battles I lost. For the purposes of our account he gave me everything I needed.

This is the story of Shuhood Abader and his hunt for abalone on the South African coast.

Shuhood Abader is a pseudonym. Names for his family members, former poaching accomplices and other figures from his past have also been changed.