Читать книгу Poacher - Kimon de Greef - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеLightning flashed at sea as the poachers cut across the flat water. Shuhood gunned the motor, steering towards the slipway with a massive haul of abalone. It was November 2006, four years into Shuhood’s poaching career and the point at which it began unravelling. Two mesh bags lay at his feet, leaking slime across the deck.

Riding with him were Shawn, a white diver he had been working with for several months, and Clayton, an old kreef fisherman from Saldanha Bay. They were returning to shore in Langebaan, a sheltered lagoon on the west coast, after diving illegally inside a restricted military zone across the bay. Following a few early snags, the operation had gone smoothly, and each diver stood to earn R10 000 for the evening. Even the thunderstorm had played to their advantage, its clouds blotting out the full moon as it rose but then discharging over the ocean, too far away to pose a threat.

Under different circumstances, Shuhood might have considered this a good omen, but from early on in the trip he had been unable to shake a sense of unease. Both his wives—an arrangement permitted by Islam—had been unusually anxious before he left, urging him to stay at home despite being accustomed to the dangers of his trade. Had he known where he was going, he said later, he would have listened to them, but he had only been partially informed of the plan.

It would be too late to back out when he found out what was expected of him.

A drug merchant in Vredenburg, a barren town of strip malls and bottle stores between Saldanha Bay’s industrial port and the whitewashed holiday homes of Paternoster, had cut a deal with some guards from a nearby military base. For a share of the profits, the guards would allow a crew of divers inside to hit reefs that had previously been off-limits—a refuge that had withstood the unrelenting hunt for abalone up and down the coast.

The merchant needed divers, but abalone syndicates were not yet established in the area. He reached out to a Cape Town contact, who passed the message to Shuhood. In debt again and eager to work, Shuhood, accompanied by Shawn, had caught a ride up to Vredenburg that week.

The thought of poaching abalone from military waters had appealed to him: it was novel and daring, precisely what was needed to get ahead in the game. Already Shuhood had dived with poachers across the country and travelled internationally, once, to harvest abalone for one of South Africa’s biggest syndicates. He was also out on bail for two separate poaching cases and could not afford to get caught.

But the guards were in on the job. Everything had been organised, the merchant promised. The payoff for working virgin abalone beds would be colossal. It was only when Shuhood learned that they would be diving in Langebaan itself—off the tip of the peninsula, beyond the Postberg wildflower reserve—that Shuhood’s assessment of the situation began to change.

He knew several divers who had tried their luck in the lagoon and been caught, losing their boats and equipment and wasting months, not to mention legal fees, grinding through the courts. The South African National Parks rangers—bokkies, he called them, after the kudu insignia on their uniforms—had offices less than a kilometre from the slipway, with a private jetty for their patrol boats. Langebaan had grown into a prosperous holiday town, with rows of villas and resorts facing the bay and an unending stream of leisure craft launching in the summer months. Most of the holidaymakers were white people, and most white people hated poachers. To Shuhood it seemed obvious: there was too much heat to dive safely. No quantity of abalone seemed worth the risk.

That night the merchant dropped them at a house with no furniture, set among anonymous rental properties on the outskirts of town. Shuhood sat up late with Shawn, swapping poaching stories, and by morning he found himself warming to the plan. Successfully navigating the illicit abalone trade requires accepting, and indeed seeking out, threatening situations, the trade ill-suited for levels of caution that most people would consider nominal. Viewed on a long-enough time axis, most threats tended to fall within tolerable limits for Shuhood.

He was in his thirties at the time, but looked much like he does today: muscular, a little below medium-height, with a bald head and straight Grecian nose. ‘It was a chance to do something different,’ he told me. The military base once more felt within reach.

The merchant brought them breakfast and drove them down to reconnoitre the water. He spoke at high pitch, wore drab clothes and in Shuhood provoked an irreconcilable conflict that had threaded through his poaching career. As an underworld businessman, the merchant had access to the capital and markets for smuggling abalone. As a drug dealer he was responsible for wrecking lives, profiting from a crime that Shuhood had considered, at times, to be punishable by death.

Mostly it was possible for Shuhood to isolate his work as a diver from the wider black market it fed into—including, at the very end, bulk swaps of abalone for tik and its chemical precursors—but when confronted by someone who straddled both worlds it was difficult to maintain the distinction.

The merchant had arranged the job and Shuhood badly needed cash, he decided. If he was a vampire who pumped drugs into vulnerable communities? Fuck him—and there were thousands more just like him.

In the parking lot one of the guards was waiting to take them across the water. The men followed him onto a semi-inflatable vessel, or rubber duck2, with a 30 hp motor, too small for fleeing patrols. Past fishing groups and jet skis they drew into the bay, crossing a line of red and white buoys marked: ‘Military zone. Keep out.’ Their destination, Donkergat, a former whaling station, had been a base for one of the South African Army’s special-forces regiments since the 1970s. Now it was a haven for abalone, the guard said.

But Shuhood had learned to be sceptical of non-poachers who spoke on such matters. He asked Shawn, who had brought a dive mask, to jump in and take a look. Surfacing less than a minute later, Shawn held up two giant shellfish.

The reefs right beneath them, he said, spitting out his snorkel, were packed.

Back on shore that afternoon, the merchant introduced them to Clayton, who would work as their bootsman, or deck assistant, keeping watch while they were underwater and helping haul up their bags. Shuhood thought him ‘a simple Simon,’ he told me; later that evening his suspicions would be confirmed. This time the merchant would stay behind, co-ordinating the pickup with a taxi driver he had hired. The guards would ensure that no patrols troubled the divers, keeping in cellphone contact with the merchant.

At 10 pm, everyone was ready.

With scuba tanks and torches the divers launched again, Shuhood holding the tiller. Saldanha Bay was a bright smear behind the hills; further to the left, the Langebaan peninsula was dark. As the shore receded, its lights playing over the water, Shuhood felt the engine stutter. He opened the throttle to avoid it cutting out. He knew from experience that this could lead to serious trouble, and had no intention of getting stuck in a faulty craft.

The engine coughed again and he let it stall, dialling the merchant. ‘Ons kannie gaan nie,’ he said, whispering even though they were far from shore. ‘The motor’s fucked.’

The first fish landed on the deck while he was speaking, bouncing and flipping at his feet. It was pale silver, slightly bigger than a sardine. Then the surface erupted and there were splashes all around them: harders, or mullet, trapped illegally by fishermen from Langebaan. A local staple, salted and dried into bokkoms, the species had been overfished, with strict catch limits imposed by the government. Locals had seen this as an attack on their livelihoods, and in defiance they had continued setting their nets.

The men on the boat felt some solidarity with their fellow fishers, but were also alert to the opportunity of salvaging a wasted night. Honour between strangers runs thin in the abalone trade, with each failure a chance for someone else to get ahead. Clayton knew a man who would buy the fish from them, he said, and without hesitation they began pulling in the nets.

The wide silence of the lagoon was broken by harders flopping onto the deck. Then a different sound floated across the water: the swish of oars as a wooden rowboat drew nearer. Someone swore at them. The vessel appeared from the darkness, with four fishermen pulling hard. ‘Who knows what they would have done had they caught us,’ Shuhood wrote. When they were metres away he yanked the engine once more, and it shuddered to life.

The merchant was waiting for them at the slipway. They hooked the trailer to the minibus and drove off. On the road back to Vredenburg two policemen stopped them: the trailer’s lights weren’t working, and they radioed a traffic officer to come issue a fine.

In the meantime, the cops ‘had a look around the boat’ and saw the ‘dive equipment and a few harders lying on the deck,’ Shuhood wrote. ‘They then shone the torches on the three of us at the back of the taxi.’ The divers had not even climbed out of their wetsuits, and were still wet. The policemen did not say anything: for catching fish, or whatever else the men had been doing, they seemed prepared to look away.

Had they known it was perlemoen the men were after—one of the most criminalised substances in the Western Cape, trafficked for enormous profits by underworld cartels—it is unlikely they would have been as lenient.

The traffic officer arrived, wrote a fine for R500, and escorted the men home.

*

The motor’s fuel pump had a hole in it. The next morning, a Sunday, the merchant had it repaired. From boats to diving rigs, much of the gear in the abalone trade is cobbled together from used or damaged parts. Entire economies exist for stolen engines. Wetsuits, from kneeling on sharp reefs to shuck abalone, wear out at the knee.

At 5 pm the crew met at the slipway to launch again. The parking lot was thronging, with bakkies queuing to tow boats in and out of the water. The divers hid their gear beneath a large tarpaulin, sure that they had avoided scrutiny. Once more they passed the military buoys and rode into the cove, where they pulled on their rigs and jumped in.

The water was clear and calm: perfect for diving. In every direction Shuhood could see abalone stuck like hubcaps to the rocks. It was a sight that he had once been used to, but not seen for a long time. The spots where he had started poaching had depleted fast as divers raced one another to pull sacks of the shellfish out. Here was what shallow waters once looked like right around the coast, wrapping from Saldanha Bay to the Eastern Cape: abalone as the dominant reef organism, feeding on algae and jostling slowly with its neighbours for space.

Shuhood began working, popping the creatures loose with a lever. He and Shawn had decided not to shuck their catch underwater, instead planning to exit the military area and work more safely on the boat. Their pouch bags filled quickly, the abalone clinging to one another as they dropped inside. Some were older than ten years and had spent their entire lives on the same set of rocks. Their feet left circular patches as the divers lifted them off: negative images, outlined by algae and encrusting corals, that would inch inwards until another abalone slid over to claim the space.

When Shuhood’s bag was full, he signalled a throat-cutting gesture to Shawn. Time to return to the top.

They had gathered over 100 kg between them, worth R40 000 or more on the black market. Before diving any longer, they had to make sure that the merchant would uphold his side of the deal. Too many times Shuhood had been short-changed by buyers and accomplices, the cash slipping away without explanation. In the poaching economy this left no recourse other than violence, and Shuhood wanted no more of that.

Dusk swept over the lagoon, lighting the sky amber, then purple. It was dark when they finished shucking, tossing the empty shells over the side. Shuhood’s wrists ached from the repetitive strain of prising loose the meat. On the horizon the storm broke, flickering behind the clouds. The men dived back in to rinse the slime from their bodies and turned back towards shore.

‘It was completely dark now and the little boat was helped along by the incoming tide,’ Shuhood wrote. ‘Neon lights could be seen in the distance and faint music could be heard coming from a local pub.’

Waterproofed inside two condoms, his cellphone buzzed in a pouch on his wetsuit. It was the merchant, his voice difficult to make out through the rubber.

‘How far are you?’

‘Amper a kilometre. Is the taxi there?’

‘No. I’ll tell you when it arrives.’

Shuhood cut the engine and drifted towards a small island opposite the slipway. Unknown to him, fifteen men with night-vision gear were watching from bushes beyond the parking lot: policemen, fisheries inspectors and bokkies, including one of the rangers who in 2002 had caught Shuhood in his first poaching bust.

Shuhood felt his phone vibrate once more. The taxi pulled up to the ramp.

He wanted to stash the abalone at the island and come back for it later, his usual method for evading arrest, but the merchant had arranged the pickup. There was no time to change the plan. Shuhood started the motor and crossed the channel, watching for signs of danger. Another boat was blocking the slipway and Shawn jumped into the water to run the bags ashore. Something was wrong: without warning the taxi sped away. The merchant reversed his car down to retrieve the boat; they would dump the abalone afterwards if necessary.

As the poachers struggled to lift the vessel, two Afrikaans men in shorts and flip-flops sauntered over.

‘Makeer julle ouens help?’ (‘You guys need some help?’)

Then there were torches in their faces and guns flashing in the glare. Watching the cops run onto the tarmac, Shuhood knew, he wrote later, that he was ‘fucked’.

*

Around the time of Shuhood’s arrest, I was finishing matric exams and preparing to begin a marine biology degree. It is difficult to imagine a life further from Shuhood’s, though our homes lay less than 10 km apart. People often say that Cape Town is a small city, though its population is close to four million. Rather, it is a big city composed of segments that seldom intersect, an apartheid vestige that produces strange distortions of time and space.

The station-deck taxi rank is like a patch of the townships grafted onto the city bowl. Kalk Bay can feel closer to Tamboerskloof than to Langa, even though it is nearly three times as far away. Shuhood moved through many of the areas I frequented—Sea Point, Simon’s Town, Kommetjie—but his world was in most respects invisible to me. It was abalone, in the end, that brought us together.

The abalone black market cuts through a parallel Cape Town, its co-ordinates reprojected on a different map. Fishing settlements separated by hundreds of kilometres lie adjacent to each other, connected to cookhouses on remote smallholdings and gang strongholds on the Cape Flats. The Chinese restaurants of Sea Point bump against abalone warehouses in Paarden Island, with Port Elizabeth’s poaching subculture off to the side. My own orbit through Cape Town had once had no contact with these landmarks.

It is a shuttered perspective of the city I will never get back.

*

After making off with tonnes of abalone and being punished with only minor fines, Shuhood’s luck, finally, had run out. For a moment he thought of rushing back into the water to swim for safety, but he barely even knew where he was.

‘Had I known the area I would have taken my chances,’ he wrote, but instead he allowed the police to shackle him and lead him to the van. The ranger he recognised was standing at the back door, watching police photographers document the arrest.

‘Here comes my favourite customer,’ he said as Shuhood was thrown inside. ‘You never learn, do you?’ The ranger had driven up from Cape Town that evening when the boat had been spotted launching. Now, catching a poacher he had been chasing for years, he could scarcely contain his delight. Three times he had seen Shuhood get away, most recently less than a year ago; this time, with more than 100 kg of abalone in his possession, it was almost certain that Shuhood would be locked up.

The men were taken to the police station and transferred, a few days later, to the Hopefield court, a single room with a small holding cell at the back. The evening before the trial, after days of silence, Clayton, the fisherman, spoke up.

‘There were people at the slipway. They watched us launch,’ he said. When Shuhood heard this, he ‘really moered that motherfucker,’ he told me. ‘He knew the whole time we were in trouble and didn’t say a word.’

From the start the trial went badly. The investigating officers had found out, from the bokkies, that Shuhood and Shawn were each out on bail for two poaching cases, meaning there was little chance of them getting out until the verdict. The prosecutor was pushing to charge the men as a poaching syndicate, pointing to the involvement of the merchant.

Within fifteen years the abalone trade had grown into an integrated black-market industry, with smuggling networks extending right across the country. Now the authorities were looking to impose tougher penalties. All four men were denied bail and remanded to Malmesbury prison while the case dragged on.

Shuhood had been in jail a decade before for a different crime, in the process becoming a member of the 26s gang. That, and the merchant’s status as a drug lord, protected the men against ‘the nastiness you read about in the papers,’ Shuhood wrote. The prisoners in the crowded cells left them well alone.

Soon enough, the merchant got out on R50 000 bail, swearing to ‘perform miracles’ and have the case withdrawn, but six months later the men were still before the magistrate. ‘Deep in the back of my mind, I knew the game was over for me,’ Shuhood wrote. In early 2007, he was found guilty of poaching and sentenced to 16 months.

He was 32, with five young children. Both his wives had given birth during the trial, their daughters separated in age by just a month. His first wife, Nuraan,3 had come to visit him in prison, lifting the baby behind the ventilation glass. ‘I thought to myself that no man should see his newborn children for the first time under such conditions,’ Shuhood wrote. His second wife, Fatima, had been forbidden from visiting by her father, and it was only after being driven to Cape Town one day—he had to appear for an older poaching court case—that Shuhood got permission to see her at home.

The wardens escorted him to the Ocean View apartment they shared, refusing to remove his handcuffs. Fatima cried as she placed their daughter against his chest. ‘I choked back the tears and I knew it was time for me to throw in the towel,’ Shuhood wrote, though it would be years until he finally did.

By the time he was found guilty for the Langebaan bust, his old cases had been struck off the roll, leaving him eligible for bail again. Before starting his sentence, he wanted to visit his family—unshackled this time—to say goodbye. The magistrate, known to the poachers as ‘Oom Jan,’ appeared to give his consent, asking Shuhood’s lawyer if he would pay bail that same day.

‘I used the lawyer’s phone in court to phone my wives and tell them the good news,’ Shuhood wrote. ‘They were very excited and started making plans for the homecoming.’

Putatively behind the scenes to fix the bail fee, the magistrate walked in again. He had changed his mind, he said: Shuhood was to remain in custody and start serving his sentence immediately.

‘I’ve been shot and stabbed more than once, but a more cruel thing than that no one has ever made me go through,’ Shuhood wrote. ‘I just sank down on the bench, dumbstruck.’

He began writing about his poaching life later that year at the suggestion of someone he met during visiting hours. A frans inmate,4 not part of the Number, had people coming to see him one day. Without protection he would have his besoek stolen—gifts like cigarettes or sweets—on his journey back to the cells. For a share Shuhood accompanied him. A middle-aged coloured woman was waiting for them behind the glass barrier.

They got talking and she asked Shuhood what he’d been locked up for. With nothing to lose, he told her about the bust. She happened to work at a local publishing house; people would be interested in his story, she said. Hearing that there might be money involved, Shuhood began working, but it was impossible to focus in his crowded cell.

It was the start of Ramadan and the Muslim inmates had been grouped together; Shuhood held the position of amir, or leader. Over a perceived slight towards Islam, a fight had broken out with the wardens. When the Muslims were split up again Shuhood asked to be transferred to the isolation ward, usually reserved as punishment for more severe misbehaviour. His request was granted. A warden found him an ancient black Olivetti typewriter to work on. Then all he had to do was write.

It was a project for which he had no frame of reference. He had never kept a journal nor paid close attention to the words he used. The last proper writing he had done was at school. Now, in a cell measuring two metres by two, he found the task extremely difficult, sometimes reworking single paragraphs for hours at a time. He tore up his mistakes and threw scrunched pages across the room. When the typewriter ribbons ran dry he broke pens to re-soak them, staining his hands and the concrete floor. His progress was slow but he kept writing, studying tafsir, or critical interpretations of the Qur’an, in between. ‘It was my best experience in prison,’ he told me. In the end, he wrote every day for seven months.

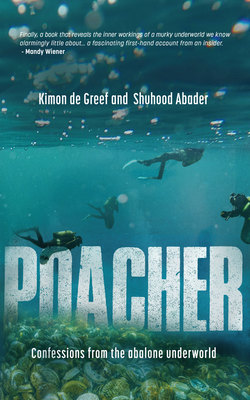

The book took form: two parts, with a prologue and epilogue, totalling more than 70 000 words; by the time we met he had begun working on a sequel. Book One began and ended with the bust at Langebaan, enclosing a circular narrative that spanned Shuhood’s rise and fall as a poacher. (I have attempted to follow his structure in this book.) From the prologue: ‘I wrote every word of this book from within the walls of prison, and this is not a book about prison and neither is it my life story, I’d rather say it’s a chapter of my life as a man who chose abalone poaching as a means to provide for his family.’

It ends: ‘Almost every day the media is rife with stories of “abalone bust” or issues related to it, and if you have ever wondered about this booming black market business and the type of people who supplied it, I suggest you continue reading. This is my story.’

*

In 2008 Shuhood was released on parole after spending more than 18 months in prison. On the outside, he contacted the publisher to show her what he had written. But she had quit the industry following a family bereavement, and was no longer interested in manuscripts. Undeterred, Shuhood ran a Google search of publishing houses in Cape Town and contacted Tafelberg, the first result that came up.

An employee read his manuscript and promptly rejected it. Shuhood was unrepentant about his crimes, the reviewer wrote. Without major revisions, there would be no prospect of bringing it to market. Crushed, Shuhood shoved his carefully typed pages with handwritten corrections in the back of a closet, where they would sit for nearly ten years.

Early in 2017, he resolved to try again.

I had just signed with Tafelberg to write a book on illegal trades, but was struggling with chronic fatigue following overlapping bouts of tick-bite and glandular fever, contracted while reporting on dagga farming in the Eastern Cape. My mouth filled with ulcers and my brain fogged up. Twice I fainted without warning, once concussing myself on a friend’s floor. I was in no position to traverse the country looking into sensitive stories—rhino poaching, illegal gold mining, trades in rare plants—and decided, around the time of my 29th birthday, to focus on abalone, a black market I had been studying off and on for half a decade and that operated much closer to home.

Completely by chance, Shuhood walked back into the Tafelberg offices less than a month after I requested to switch projects, carrying his manuscript in a plastic packet. My editor mentioned to him that another writer was interested in abalone. He looked me up and sent me an email that same week.

This is what I received, unedited, on 13 April:

Hi my name is Shuhood I have not heard about you until today, I am a abalone poacher since 1996 and in 2007 during my imprisonment I wrote my story is it possible that you could contact me regarding my manuscript that is due for review at the publishes I would highly appreciate any kind of your professional input/assistance. My contact no is ********** or email me at this address. Regards Shuhood

We met at Kenilworth Centre, a grim mall on the outer rim of the southern suburbs, facing across the M5 to the Cape Flats. It is a different node of consumer culture to the Cape Town malls of my youth. Muslim men in flowing thobes push laden trolleys from Game. The freestanding stalls in the corridors sell fidget spinners and vape accessories, not tourist curios (the Waterfront) or manicures and jewellery (Cavendish Square). White shoppers are in lower proportion. The facilities are plainer and more utilitarian, designed less for leisure than channelling people through.

Shuhood was waiting for me in the food court, wearing Aviator-style sunglasses and a black fez. The manuscript was in a backpack at his feet. We spoke for more than two hours. Keeping track of what he said was like drinking from a fire hydrant. Stories rushed from him, rendered with a precision I had never encountered in a subject. He remembered how the sky had changed colours sixteen years before as he drove a haul of abalone into Hout Bay; how the first time he had seen abalone harvested at night the shells had glowed with phosphorescence.

But he did not want me to write about him. Rather, he wanted help rewriting a conclusion for his book, working in the remorse his original reviewer had requested. Remorse, to me, seemed beside the point, with an inside view of the abalone black market on offer, but I asked to read the manuscript.

Its raw detail was astonishing. Missing from the sketches—boat chases, near-drownings, shark scares—were two elements, I thought: Shuhood as a character and a contextual frame for understanding the trade from which he made a living. I made a case for working together and gave him as many reasons as possible to refuse it. The royalties would be less than he had hoped for.5 The project would take months to complete. I would need to interview him, meet his family, rummage around in his past.

To my surprise and alarm, he said yes.