Читать книгу Poacher - Kimon de Greef - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TWO

ОглавлениеThe neighbourhood where Shuhood’s family lived for generations was destroyed a few years after he was born. He still visits sometimes, an interloper among the retirees and tourists and uniformed naval staff who vanish through the harbour gates.

Simon’s Town was until the late 1960s home to more than 7 000 people designated ‘coloured’ by the apartheid government and then forcibly removed, under the Group Areas Act, to dormitory suburbs in Ocean View and across the Cape Flats. A close-knit Muslim community with roots stretching back to the slave trade was pulled apart, their homes knocked down or sold to white buyers and the mosque they worshipped at, spared demolition by the authorities, rendered into a visual anomaly: green minarets and cornices rising among bland seaside houses, as if deposited there by a strange tide.

As a young man, Shuhood used to pray at that mosque before poaching abalone in False Bay. When he finished, he would eat fish and chips on the jetty where his father had swum as a child. Much of his life has threaded through Simon’s Town, but the roots binding him there, if not fully erased, have been smudged out.

‘White people look at me here like: “What the fuck are you doing? You don’t belong,” he told me. ‘I think to myself: “No, you don’t fucking belong here. I’ve got a lot more right to be here than you. My birth certificate says Simon’s Town, place of birth”.’

By genealogy he has a stronger claim than most residents today. His great-grandfather, a stonemason, moved to Simon’s Town from Claremont in the late 1800s, marrying into an old Muslim family and by extension all the families connected to it—the fabric of what became known, over the decades, as the Malay Quarter. His great-grandfather’s surviving handiwork includes the moulded gates of Admiralty House, a naval residence that later became a national monument and, much later, a landmark for Shuhood to orientate by while diving abalone offshore.

Shuhood’s grandfather was also a builder—‘all my uncles and them were tradesmen’—and member of the Labour Party who once travelled to the Soviet Union on a worker’s delegation. ‘He looked like a white man,’ Shuhood said. ‘I’m dark, but my father and them are like you: green eyes or blue eyes, with fair skin. They say my great-great-great grandmother was Irish, O’Malley or something, but I can’t remember her name.’

Shuhood’s family had become moderately prosperous by the time of his birth, establishing in the Malay middle class. Among Shuhood’s uncles are lawyers and academics, stern Muslims all, who look down on him for becoming a poacher; one of them still refuses to speak to him at family gatherings. But instead of growing up in Simon’s Town with his relatives next door, Shuhood came of age in Grassy Park, where on the streets children from rougher backgrounds picked on him for being soft.

‘I was a good-looking laaitie, coming out of a middle-class family,’ he said. ‘With these underprivileged kids, I always had to prove myself.’

To hold his ground in the aftermath of apartheid’s urban purges, he acquired a new persona: unafraid of fighting anybody, quick with a knife. How much did this determine who and what he became? It is an impossible question to answer, even for him. ‘I’m where I am now because of decisions I made,’ he once told me. ‘I’m from a good family and could have done more with my life. This didn’t happen just because we were evicted.’

Another time, he said: ‘If we stayed in Simon’s Town I’d be in the navy or working in the docks now, like my people before me. I’d never have gotten mixed up with the gangs. Poaching? Maybe, maybe not.’

*

The Malay Quarter rose above the harbour in Simon’s Town, a cluster of whitewashed homes and cobbled lanes overlooking False Bay. Even before Shuhood was born, its final days were drawing near. The Group Areas Act, passed in 1950, forbade the existence of racially mixed neighbourhoods in South Africa, and it was only a matter of time before Simon’s Town became a target.

From its origins as a winter anchorage for the Dutch East India Company in 1743, the settlement had always been racially diverse, with slaves from China, Indonesia, India and across the African continent, including Khoisan people, living at close quarters with settlers from Europe. The town grew rapidly in the 1800s after Britain took control of the Cape and began building a naval base there, drawing an even wider mix of people. By the 1950s, the area had become a creolised port town, home to overlapping communities of white, black, coloured and Indian people—all four categories of the apartheid racial scheme.

This presented the National Party, elected just a few years earlier, with a microcosm of a bigger challenge: how to unstitch centuries of natural drift between different racial groups and forge homogenous, geographically distinct neighbourhoods in the country that they had come to rule. Their solution wrested Cape Town from being South Africa’s most integrated city in 1950 to its most segregated less than thirty years later—a condition that has largely persisted since the end of apartheid, locked in place by the highways and railways laid down to keep people apart.

In the process, according to the social geographer John Western, one in six coloured people were expelled from their homes, compared with just one in 666 whites.

The first proposal for enforcing Group Areas legislation in Simon’s Town appeared in a local paper in 1959. It included provisions for allowing coloured and Indian residents to remain living there, but was replaced, five years later, by a new plan reserving the entire town for white people.

‘Representatives from the Roman Catholic, Anglican and Methodist churches, the Mosque Trustees, Ratepayers Association, Chamber of Commerce, the Black Sash local branch, various sporting bodies and clubs, and all the non-white organisations’ came together to oppose the announcement, wrote Barbara Willis, a prominent activist, in a paper she presented at the 1968 Black Sash Durban conference.

The committee sent submissions to the Group Areas Board, collected signatures for a petition and raised money for legal action ‘to put the case for the united townspeople,’ Willis wrote. At a public hearing in 1965, ‘there was no objection from any section of the community or from any racial group against each other,’ only sworn testimonies from residents who saw no need for segregation. But on 1 September 1967 ‘the guillotine fell’ and the entire municipality was designated a white area.

Remonstrations to the national minister of planning were unsuccessful. The first removals would take place within a year. In a letter to the Argus soon afterwards, Willis’s husband, Humphrey, a local councillor, proposed erecting a gravestone in the middle of town:

Simon’s Town is dead—murdered by the Group Areas Act. It will, of course, continue as a collection of buildings in which people work but the spirit of the place is departed … A living entity has been destroyed. What have those who perpetrated its destruction given in its place? Nothing—a blank. Therefore, let the place be renamed ‘Blancville-by-the-sea’. And you can spell it as you like—Blanc, Blank or Blanke. They all mean the same—a town without a soul.

*

Shuhood’s mother, Rosa, had already felt the squeeze of forced removals by the time of Simon’s Town’s demise. She had grown up in South End in Port Elizabeth—among the first neighbourhoods razed in the apartheid government’s quest for racial segregation.

Set in the heart of the city, on a low hill above the harbour, South End was home to ‘English and Afrikaans-speaking Caucasians, Malays, Coloureds, Indians, Chinese, Jews and a mere handful of Africans,’ writes Yusuf Agherdien in South End, Then & Now, a book juxtaposing historical photos of the suburb—brick row-houses, crowded streets—with the vacant fields that replaced it.

The cleared land is still visible from the air today: a scrubby wasteland, only partially filled in by new buildings, punched out from the urban grid. Rosa lived there once, one of fourteen siblings, with a large extended family within walking distance. She was twenty years old when she met Shuhood’s father, a carpenter for RH Morris Builders renovating the Provincial Hospital down the road. He was lodging with an aunt of hers, had blue eyes and pale skin, and was, she thought, the most handsome man she had ever seen. Marriage followed quickly—his family drove up for the wedding—and when his contract ended they decided to move back to Simon’s Town, taking a small cottage two doors away from his parents.

‘The stoep looked right over the sea. It was so beautiful and blue. And the mountains—it was amazing,’ Rosa said.

From their doorway it was a three-minute walk to the Simon’s Town harbour, where local fishers sold their catch, including perlemoen.6 There was no vehicle access to their home and they parked their car, a Ford Zephyr with orange seats, on Jubilee Square, trekking up the steps with their groceries. At first Rosa was homesick, but the community she’d moved to was very similar to her own. There were old families—Manuels, Bakers, Slaamies, Fakiers, Appelbys, Jenkinses—connected to each other through marriage, binding over generations into a kinship network that soon welcomed her in.

Their lives revolved around the mosque, built in 1926, that today mostly stands empty, tucked behind the Main Road coffee shops and clothing boutiques. Up the hill lay a kramat, or shrine, for two Indonesian imams, exiled to South Africa in the eighteenth century. At the Seaforth Cemetery—beside sections for war victims, Boer prisoners of war, Russians and Italians—was a Muslim burial ground. (The kramat is still there, incongruously wedged among expensive houses, but the burial ground has been destroyed by vandalism.) During Ramadan, children filled the streets before sunset, delivering gifts of food between families preparing to break the fast. When Eid came, the muezzin’s prayers rung out until dawn.

The mosque’s imam, Mohammed Baker, was widely respected as an Islamic scholar, and had published the first Afrikaans translation of the Qur’an in 1956. Three years later, he addressed the Group Areas Board when their intentions for his hometown became clear.

‘My father and his father and his father’s father were born and bred in Simon’s Town,’ he told them. ‘We have been there for 200 years. I will lose my birthright—my ancestors were the first people to settle in the area. If I move to Bonteheuwel, I will become nothing, merely a number. They have no hospitals, no police station, no church, no school. A man can be subjected to such disintegration that he will lose his spirit.’

Rosa’s family began losing their homes in South End in 1965, a year after she had moved away. ‘Group Areas started in PE and spread down here,’ she said. ‘It was traumatic. We lived right near the beachfront, but they said we were too black and we had to leave. They pushed us right out to Galvandale, which is now the so-called coloured area. And they started with Cape Town a few years later.’

Among the first and most visible targets for the apartheid town planners was District Six, the flattened residential neighbourhood that still scars the city’s slopes. From the late 1960s more than 60 000 of its coloured residents were ejected to new housing projects on the Cape Flats, joined by thousands more families from other ‘black spots’ identified by the apartheid government: Salt River, Observatory, Mowbray, Claremont, Wynberg, Tokai, Bergvliet, Plumstead, Constantia, Bishopscourt, Simon’s Town.

‘You had to get accustomed to the neighbours,’ said Rosa, who in 1972 relocated to Grassy Park with her husband and two children. ‘Group Areas threw the people out and they just had to come.’

‘When you meet a coloured person in Cape Town,’ Shuhood told me once, ‘you don’t ask, “Where are you from?” You ask: “Where are your mense from?” Your people. We speak about the old places, not about Hanover Park and that.’

Most of the evicted Simon’s Town residents moved to Ocean View in Kommetjie, another freshly poured housing project that would soon devolve into a ghetto. At first the hillside settlement was called Slangkop, or ‘Snake Head,’ a name that so distressed the new arrivals that they began referring to it as Upper Fish Hoek. Before long, officials renamed it—bringing to mind, one imagines, both the lost view of False Bay and its more distant Atlantic replacement.

The government’s plans for Ocean View included schools, an old-age home, playgrounds, a cinema, a shopping centre, a community hall and several churches, but none had been completed when evictions began. Many never would be.

‘Street lights are not yet functioning because they have run out of cable and the only telephone is in the Housing Supervisor’s office which is closed at night,’ wrote Barbara Willis in 1968, several months after some 70 families had already moved across from Simon’s Town. ‘There are no halls, no library and no police station, and there is already some hooliganism there, and also a shebeen or two.’

The local MP had tried to get a police station built or, failing that, a smaller satellite post, but was refused on both counts.

When given notice under Group Areas, families had three months to vacate their homes and accept whatever new housing the government offered them. Alternatively, they could state, in writing, that they would find new accommodation for themselves. But Cape Town was already beset by a severe housing backlog—there were 12 000 names on the waiting list for rental housing in 1967—so most people did not consider this an option.

The first families to move to Ocean View had been categorised ‘sub-economic’ by the government, earning less than R60 per month, and had their goods transported from Simon’s Town by officials from the Department of Community Development—considered a gracious gesture at the time, as the law held residents responsible for their own removal costs.

‘A senior official helped, together with the Simon’s Town housing supervisor, and worked late into the night,’ Willis wrote. Families with chickens ‘were allowed to take them provided they killed one a week until all were consumed’.

*

Shuhood’s life as a poacher would wind through both Simon’s Town and Port Elizabeth. His first dives for abalone took place a few kilometres from his parents’ demolished cottage. The first time that he was caught poaching, he spent the night in the Simon’s Town cells.

Years later, diving behind the naval harbour one afternoon, he stashed his abalone to retrieve after dark and was walking back to the parking lot when he saw a man watching him with a strange expression. As usual, his response was to play it cool. ‘I greeted the guy like I had nothing to worry about, but he didn’t stop staring,’ he told me. ‘So I look down and there’s this fucking shucked perlie stuck to my wetsuit! Right in the middle of my chest! Broe, I got out of there quick.’

It is possible to detach an abalone from its shell without killing it, severing the muscle, but the shell never grows back. Shuhood had missed a step and the creature had clung onto him. It was, for him, an uncharacteristic mistake. He was known for delivering clean fish to his buyers: ‘Die Kaap se skoonste duiker,’ or Cape Town’s cleanest diver, they called him.

‘Some people work downright mossag. Messy, man,’ he told me. ‘Fish with guts in, and everything is just slimy. You can’t go to the buyer like that. Now you must pay someone to clean your shit properly. Some of the carriers do this—’ he bit the air with the side of his mouth. ‘Bite that guts, rip it, spit it out.’

Many times he returned to the same spot to poach. Penguins from the Boulders colony plunged through the water or watched him from shore. Further out, beyond the shallows, Shuhood knew, were great white sharks, but in the beginning there was no need to risk swimming there. Abalone plastered the reefs close to land, enclosed by thickets of kelp. Over time, as poaching grew worse, the abalone thinned, empty shells littering the seafloor. Shuhood was among a minority of divers prepared to go deeper.

‘If you swim out, that’s when you worry,’ he told me. ‘You try not to think. You’re always being aware, but if you think shark shark shark you’re not gonna get any work done.’

Using his dive lever as a kind of ice pick—stabbing it into the sand, pulling himself forward—he would crawl along the bottom, protected against being struck from below. On the deeper reefs were massive abalone that he called ‘buckets’.

‘There’s a prayer I said every day,’ he said. ‘Oh, Allah, protect me from the sea and the dangers of the sea.’

On a recent Saturday morning, Shuhood and I took a drive to Simon’s Town, cutting through the council flats near his house (‘the ghetto,’ he said) and merging onto the M5, one of the apartheid barriers separating the white suburbs from the Cape Flats. The highway passes Grassy Park, Lotus River and Lavender Hill—a very different approach to Muizenberg than the M3, the route via Constantia I have taken most of my life. Our paths through the city have been circumscribed and separate; without abalone, there would have been no reason for them to intersect.

On the way down the peninsula we stopped at some of Shuhood’s old poaching spots. We arrived in Simon’s Town at noon. A parking attendant waved us into a space opposite Jubilee Square, where sellers of African crafts waited for business. In the harbour there were a few small tour groups milling about, with adverts for kayak rentals and whale-watching trips strung up along the quay. Simon’s Town felt empty in spite of all the people there: a naval port crossed with a dour holiday town at the end of the railway tracks.

It was a mood that I had felt there long before learning about its Group Areas history—a strange vacancy. Blank.

We ate at the fish and chips shop. Shuhood told me a story about his father, as a child, bunking school to go swimming. ‘He was in the water alone when he saw this massive shark come into the harbour. He just made it up the stairs, then he sat here and watched the shark.’

After lunch, we crossed the road and climbed the stairs to the mosque. ‘One of my aunts used to live here; an uncle lived there,’ Shuhood said, pointing up and down the lane. ‘Some people stayed longer than us.’

With his parents he would visit the Malay Quarter each year for Eid, driving through to other family in Ocean View afterwards. Before leaving, they would go to where their old home had once stood.

‘My father would tell me, “This is where we lived,” and I didn’t understand what he meant. I was like, “But why don’t we live here anymore?” And he’d say, “I’ll tell you another time.”’

We walked down Thomas Street, a narrow road with views of the harbour. A car slowed and the driver turned to look at us. At another stairway, Shuhood stopped.

‘We lived somewhere here,’ he said, ‘but the houses have all changed.’

*

Rosa lives today on the Cape Flats train line in one of the middle-class coloured suburbs that hug the outer edge of the M5. She is in her seventies and hard of hearing. Shuhood would often visit her before going diving, and when he left she’d watch his WhatsApp profile until he was back online. ‘Oh, but I used to worry! That’s when I knew he was safe.’

Her house is small, with a peeling fence and covered stoep. She rents rooms in a backyard Wendy house to Zimbabwean lodgers who enter and leave through a side gate. Her youngest son, a heroin addict who stays clean for months before relapsing, sleeps in the second bedroom sometimes; recently Shuhood was threatening to throw him out.

The first time I visited, a week after meeting Shuhood, I was expecting a more distressing set of circumstances. Shuhood had told me by WhatsApp that he was ‘tikking’ at his mother’s house, but he meant typing the sequel to his manuscript—on a borrowed typewriter, hunched over in the kitchen—not getting high.

On a December weekend in 2017, Rosa went for a drive down the peninsula with two friends. By chance they ended up in Simon’s Town just before the noonday prayer, and at Rosa’s suggestion they parked on Main Road and climbed the concrete steps. It was her first time inside the building in more than 20 years. ‘It brought back so many memories,’ she said. ‘You get that sad feeling, you know? I thought to myself: “I should have still been here. I should have still enjoyed coming to this mosque.”’

On the way out she looked at the square where their car once stood and the harbour where children from the neighbourhood used to swim. It was as if she was switching between two views of the same place.

‘I wish my grandchildren could have grown up there. I wish that my own children could have enjoyed what those other children did,’ she told me. ‘When I go to Simon’s Town now, I could cry.’

*

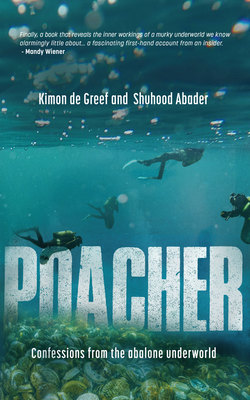

It is in South Africa’s chinks and fissures that the illicit abalone trade has taken hold. Forced removals took place less than two generations ago. Legacies of dispossession that began long before apartheid are still playing out. Not everyone who inherits this history turns to a life of crime, but by any measure the likelihood is far greater.

As a teenager in Grassy Park, Shuhood wore his hair spiked and dressed sharply: Pringle shirts, Navada slacks, Crockett & Jones leather shoes. The black market was not an abstract concept but operated in front of him on the street. The Americans fought for turf with the Junky Funky Kids, extorting local businesses and peddling buttons (mandrax) and dagga. It was the mid-1980s and South Africa’s criminal economy was still parochial, hemmed in by trade sanctions and the hard borders of the apartheid state. A decade later it would spring open to the global underworld, with the same gangs at war with each other. Abalone, among the Cape’s most valuable commodities, had become embedded at the system’s nexus. The preceding steps, meanwhile—the systemic dislocation of millions of people—were blurred from view, absorbed into the city’s built environment. Blancville conformed to the white city. If you type into Google’s search box ‘Simon’s Town Group Ar—’ today the auto-fill suggestion is ‘art group’.