Читать книгу “If we had wings we would fly to you” - Kiril Feferman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

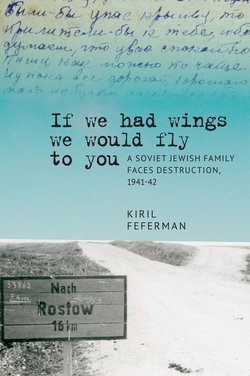

This book is about one Jewish family, which was swept away by the Soviet-German War, the German invasion of Soviet Russia and the Holocaust—the Ginsburg family. The study draws largely on the letters that the members of the family sent to Efim Ginsburg, who was living in Soviet Central Asia. The letters cover a time span that was crucial for Soviet Jewry, stretching from the start of World War II to the murder of almost the whole Ginsburg family in August, 1942, during the Holocaust. The letters touch on many themes, including the wartime atmosphere, the correspondents’ worsening living conditions, and, of course, the crucial question of evacuation.

The evacuation of Jews from the North Caucasus differed from the evacuation (of Soviet citizens, including Jews) from many areas that were quickly overrun and occupied by the Germans at the beginning of the Soviet-German War. Over many months, from 1941 to 1942, the frontline between the German and Soviet army positions remained static in this region. This allowed more time for the Jews living in the region to decide whether or not to relocate; significantly, this period provided an opportunity for the Jews to create written records, such as correspondence, which enable us to examine their decision-making processes. However, most such correspondence was lost in the maelstrom. The collection of Ginsburg letters preserved in the Yad Vashem Archives in Jerusalem is one of these rare records, as it sheds light on one Jewish family’s long period of hesitation about evacuating from their home in Rostovon-Don. I have employed this rich collection of Ginsburg family letters to illuminate the plight of the Jewish population of the North Caucasus, as Jewish family members deliberated and argued amongst themselves, over and over again, and finally made the fateful decision—whether to stay in their familiar local area, or to leave.

At the time of the German invasion of the USSR, the Ginsburgs, a Jewish family living in the city of Rostov-on-Don in southern Russia (the Russian gateway to the Caucasus), numbered eleven people, spread over three generations. Among the adults there were six women and three men, several of whom took part in the correspondence. The only member of the Ginsburg family living away from Rostov-on-Don was Efim Ginsburg (1897–1973). He was the recipient of almost every letter in this collection, and he managed to hold on to the collection and keep it safe, during and after World War II.

The Rostov-on-Don Ginsburgs (in fact, the family split up several times, but always remained close to the city) badly miscalculated the events of 1941 and 1942; they stayed in the Caucasus region and perished during the German occupation in the summer of 1942. Vladimir (Volodya) Meerovich, the sole family member from the Rostov-on-Don branch who wasn’t murdered with the others, had been drafted into the Soviet army before the German attack on the Caucasus in June 1942; he survived until mid-1943. When he learned what had happened to his family, he began to take personal revenge on the Germans, by participating in some reckless reconnaissance raids. Life expectancy in these army units was extremely short.

The changing tides of the War had a direct impact on the correspondence. We can glean from the letters the unmistakably gloomy and deteriorating atmosphere, which was increasingly evident as the German armies approached the North Caucasus region the first time, from late summer to fall, 1941, and again in the summer of 1942. In contrast, the letters written in the early summer of 1941 and in the winter to spring of 1941–1942 are optimistic, citing both the real and imagined triumphs of the Red Army. Written in a country known for its keen interest in the inner thoughts of its citizens, these letters also could be read with an eye to the Ginsburgs’ fear of the Soviet censorship, real or exaggerated.1 Viewed from this perspective, the book sheds new light on the limits of what was permissible under Stalin2 or, framed more broadly, on the principles of communication between people in the USSR.3

This communication revolves around one main issue that permeates all the letters—evacuation: that is, if, when, and how the family should leave their home city, in order to evade capture by the Germans. It should be remembered that, in ordinary situations, people do not abandon their homes—it takes the direst of circumstances to convince them to leave. If someone has no way back, for one reason or another, he becomes a refugee.4 On their way to a new life, refugees may cross borders, and, in case of hostilities, even front lines, ceasefire lines, etc.

Economic factors bring an additional dimension to this story, creating a constant and nuanced interplay with “life and death” factors. The greater the danger threatening potential refugees, the less place economic considerations played in their decision-making, responding to immediate threats. Other refugees made their decisions more as a strategic choice, that is, not in response to immediate threats, and as a result, they often avoided being trapped in a dilemma between “life and death” factors and economic calculations. Still, all those who considered evacuation had to reckon with the fact that they would incur many expenses due to their flight and subsequent resettlement, resulting in their impoverishment.

The flight of Jews from the Soviet Union’s western regions into the interior, in the initial phase following the German invasion in June 1941, placed them in the category of refugees, as broadly defined above. Generally speaking, Jews who remained in territory under German rule faced the danger of physical extermination, but this is knowledge we only possess a posteriori. Soviet Jews considering flight could not acquire any definite and direct facts about what awaited them under German occupation. The physical destruction of Jews began only after June 22, 1941, and the Germans did their best to keep it a secret. Jewish flight from the deadly reach of the Germans should be viewed against the background of the Soviet evacuation program. This was a large-scale state-run project, aimed primarily at safeguarding the Soviet military industries and the manpower they employed from being taken over by the Germans. These state employees, often with their families, were evacuated, by government orders, to the country’s hinterland; there were also Jews amongst this group. In addition, there were others who were ordered by their local employers to continue working, even until the last days of Soviet rule. With the exception of these two categories, all the others had to decide on their own whether or not they wished to join the evacuees, and to act accordingly. It was on them that the evacuation program had the biggest impact, by creating a certain psychological climate. This amounted to a paradox, as the totalitarian Soviet regime, preoccupied with its own survival, left masses of people to decide for themselves. Thousands of individual Jews had to make the fateful decision, alone, whether or not to leave their home and seek shelter elsewhere.

For residents of Rostov-on-Don, this decision was based on what they thought about the course of the Soviet-German War, and the likelihood and danger of German occupation of their city. Their perceptions were influenced in turn by the news they were hearing and reading, which was often a function of how the Soviet media presented such information. The Soviet media, an important, and often the only official news supplier, was not regarded as trustworthy by many Soviet people. However, its coverage created a certain climate, as did the specific measures that the local authorities implemented (even though we do not know for certain how the population, Jewish and non-Jewish, interpreted what they heard and read). These factors affected the decision of individual families about whether to stay or to go, along with other factors, such as age, gender, family situation, employment status, opportunities for evacuation, and the procedures to be followed, as well as fears about the dangers involved in the evacuation process itself. The Ginsburg letters, although written to pass censorship, do mention at least some of the factors that they were considering in determining what to do.

It could be anticipated that Soviet reporting would be confusing, as it reflected Soviet ideological maxims, including the claim that the Germans targeted all groups under their domination, not only the Jews.5 Likewise, it could be expected that the Soviet media would be torn between the mutually exclusive goals of calming the public and raising people’s spirits, by providing news during the War while not sowing panic.

But probably the most crucial question concerns the reliability of the Soviet media in the eyes of its consumers, and most specifically, in the eyes of potential evacuees. By the outbreak of the Soviet-German War in June 1941, the Soviet media was widely viewed as the most important instrument of propaganda, but not as a reliable supplier of news.6 In order to gain the confidence of its audience, or to put it simply, to make people believe its reports, the Soviet media definitely needed more than just to exercise a monopoly in supplying news; its news had to look credible to the Soviet people. Given the dubious reputation of the Soviet media in the eyes of many Soviet people, it is likely that the Jews had to rely on their ability to read “between the lines” in order to grasp the hidden messages, and especially to understand the course of the War. On the whole, as long as they perceived the situation as being relatively stable and did not view it as a clear mortal threat, then “conventional,” that is, cost-benefit considerations played an important role in the decision-making of some Jews regarding evacuation.7 But, once the situation became or seemed to become critical, economic factors were increasingly dismissed, and then Jews fled or attempted to flee, irrespective of all other arguments.8

With the benefit of hindsight, a contemporary reader might surmise that the correct answer to the dilemma confronting Soviet Jews in the threatened areas as to which would have helped them decide the best time to escape was to leave when the situation remained relatively calm, there was no disorder, personal property could be sold at a good price, and the Soviet evacuation program, not yet overstrained by an excessive influx of refugees, still functioned properly. The ideal destination for the evacuees would be one that offered a relative abundance of food and a milder climate, connections that could lead to employment, or, more broadly, help refugees survive there economically, and finally, was far enough away from the German armies.

If official sources did not suffice, Soviet Jews had to turn to indirect sources of information. Consequently, Jewish refugees moving into the Soviet-controlled area and talking about the German persecution of Jews appeared to be the most trustworthy sources of information. Indeed, Jewish refugees who fled from the German-controlled part of Poland (they came into the Soviet Union from September to December 1939), and those escaping from the western regions of Soviet Russia (after the German invasion of the USSR on June 22, 1941) could share with Soviet Jews what they knew about the various forms of anti-Semitic persecution, including sporadic killings.9 But, as mentioned above, they could not tell the Soviet Jews about the all-encompassing genocide of the Jews in their homeland because it only began after June 22, 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

But not every Jew contacted the refugees. Some were discouraged from doing so by Soviet admonitions against spreading alarmism. Furthermore, at times the influx of refugees would cease, if the frontline stabilized. When the flow of information coming from the refugees was cut back, and the role of other informal sources for one reason or another also decreased, the result was an information void. In such a situation, the proportional influence of the Soviet media would increase once more.

Viewed from a general perspective, this book considers the many factors affecting the Soviet-Jewish evacuation to potentially safer Soviet territories, far from the danger of German occupation, during World War II: the availability of information, individual discretion and consideration of outside factors, the effects of spontaneous relocation, and new local hostilities. Another key factor was what the local authorities did or did not do to encourage or facilitate evacuation. Finally, the big question is what evacuation opportunities and resources were available in Rostov-on-Don (and who could take advantage of them, and how), which could be another source for documenting patterns of flight.10 While focusing on the evacuation of one Jewish family, the book considers their situation as a case study of the larger issues involved in evacuation. The Ginsburgs’ personal deliberations and reflections and their recurring hesitation are set against the background of major wartime events in their region and in their home city of Rostov-on-Don, between 1941 and 1942. These events included the abrupt change from a peaceful life to destitution as a result of the German bombardment, the German capture of Rostov-on-Don in November 1941, its subsequent recapture by the Red Army, which held it for seven months, and the fall of Rostov-on-Don to the Germans, once again, in July 1942.

The major points of the book are to describe the Holocaust and the Soviet-German War through the Soviet Jewish lens.11 The book seeks to find an answer to the painful question that haunted the pitiably few survivors from this family: why didn’t the Ginsburg family escape to safety? Unlike Leningrad under siege,12 Rostov-on-Don was not encircled and it was possible to leave the city, during most of the period under study. Who bears the responsibility for this family’s fatal decision not to leave, in 1942, while they still had the chance? During that time, the German genocidal actions against Jews became known, and indeed some Jews were killed when Rostov-on-Don underwent the first brief German occupation, in November 1941. Although the Ginsburgs could have left the city before the first German attack, they did not do so. They conveyed their feelings and assessments of their situation, in letters to a relative who was living in a safe territory. The rich collection of correspondence between the members of the Ginsburg family helps us to understand their seemingly illogical decisions, and, more generally, to study some of the basic issues confronting Jews in a world threatened by a German invasion: the availability (or lack) of information, the attitudes of local authorities and local population groups, the changing tides of war and the knowledge of the mass murder of other Jews, the impact of these factors on individual Jews and their families, and, lastly, the fateful and difficult decisions that they themselves had to make.

Until recently, scholarship—whether Western, Jewish, or Soviet/Russian—has ignored the personal experiences of Jewish refugees in the wartime Soviet Union. The studies made of the evacuation have mainly been based on the official Soviet documentation.13 In recent years, more studies have been published, analyzing the experiences of evacuees sent to remote Soviet regions, far away from the battlefields of the Soviet-German War.14 Refugees who were transferred to these areas were not directly threatened by the German onslaught. The experiences of refugees who were living in the areas that faced an immediate German threat (or who escaped from one threatened zone into another) are usually only mentioned in passing.15

One reason for this is that the question of evacuation or escape is one of the more elusive Holocaust subjects because the process is difficult to trace and analyze. The events resulting in Jewish flight were kaleidoscopic because Jews in immediately threatened regions often had to make critical decisions within just a few hours, based on a spontaneous reaction to dramatic events, such as the news of a German land offensive in the area, or the experience of German bombardments. As a result, few refugees left written records of their experiences in real time. Those fortunate enough to reach a safe haven, far from the threat of the German army, endured enormous hardships along the road, which often dominated the saga of their flight. Unfortunately, little information is available in the official records of Jewish escape into Soviet territories that were safe from the danger of German attack.

When the Jews considered the pros and cons of their flight from potentially threatened Soviet territories, they also had to take into account their ability to overcome numerous obstacles, including the attitude of their employers and the authorities in charge of issuing the necessary authorization. Another aspect of evacuation involved the need for the Jews to mobilize all their financial resources, an essential step in preparing properly for a long journey with an uncertain ending. Ideally, nothing valuable would be left at home, since there were no guarantees that they would be able to return to the same property, and because people anticipated that evacuation, although formally a free-of-charge state program, would nevertheless turn out to be an expensive undertaking. To cope with this problem, the preparations for evacuation involved converting their savings into easily movable valuables. In addition, although few people still owned their own homes in the Soviet Union,16 the fate of the property (whether the evacuation would affect their eligibility to move back in again when they returned) weighed heavily on potential evacuees.

There was also the necessity to plan in advance for the care of people with special requirements, such as children and the elderly, to prepare for cold winters (procuring warm clothes) and economic uncertainties (it was worth taking items such as sewing machines, which would help their displaced owners find part-time work and survive in the future). Finally, evacuation proved to be largely a women’s concern because an ever-growing number of men had been called up to the army. So the women had to figure out whether and how they would be able to organize their own and their dependents’ evacuation.

It should also be realized that evacuation was not a guaranteed recipe for survival during the War. The advancing Wehrmacht troops sometimes forestalled the Jewish refugees, many of whom perished sooner or later in the German-occupied territories. Other causes of death were German bombs dropped on the trains carrying evacuees, starvation and illness when on the road and at the places of destination. Even the below-minimum supplies of basic food and commodities supposedly guaranteed and provided by the Soviet state were frequently unavailable. As a result, landlords, merchants, those involved in transporting the escapees, robbers, and many others exploited the Jewish evacuees’ plight. However, in spite of all these problems, it should be clearly recognized that the evacuation did give the Jews a chance to survive, which they would not have had if they had stayed in the areas occupied by the German army.

In terms of the book’s structure, I have set the scene with three background chapters. In chapter 1.1, I have briefly outlined the history of the Jewish presence in the North Caucasus, from their first settling in the region to the outbreak of the Soviet-German War in 1941, interwoven with the prewar history of the Ginsburg family. In chapter 1.2, I have analyzed the movement of civilians in the wartime Soviet Union, focusing on the movement of evacuees into the North Caucasus.17 Chapter 1.3 gives an overview of the murder of Jews in the North Caucasus during the German occupation. However, the occurrences in the city and District of Rostov18 have been interwoven in the chapters that directly refer to the Ginsburg family correspondence. By the same token, other relevant topics, such as the warfare taking place in various parts of the region and evacuation from the North Caucasus are integrated in the analysis of the Ginsburg family correspondence because the family explicitly discussed these subjects.

There are one hundred and sixteen letters in the Ginsburg correspondence, and also many unsorted pages. Some of the letters are long, covering many pages, containing discussion and information, and expressing the writers’ emotions; others are condensed on postcards, where much had to be put on just one small page; there are also telegrams, with the briefest information. All the letters, except for the telegrams, were handwritten in Russian. From this collection, I selected and translated ninety-nine items that seem to best illustrate the themes of the book. Furthermore, some letters have not been translated in their entirety—often I only selected parts of the letters for translation. What guided me in the selection process? The most basic consideration is that the letters are extremely repetitive. One of the main explanations why they sent so many letters, sometimes more than one on the same day, is that the senders were not certain, and justifiably so, that their letters would ever reach the addressee. (The other explanation is probably the repetitive style favored by the authors themselves.) Although it is no doubt important for readers to know that some themes were particularly recurrent in the correspondence, reproducing all the letters would—in my opinion—make the book difficult, if not impossible, to read. In addition, in a small number of cases, it was impossible to identify the author and/or the date of the letters. Basic information about all the letters, including those not translated for the book, can be found in a list of the letters, at the end of the book, before the Bibliography. This information is also present in footnotes scattered throughout the book, in the most appropriate places, chronologically.

The analysis of the letters written by the members of the Ginsburg family constitutes the bulk of this book. I have divided the letters into three parts: those written in 1941, 1942, and 1943. I have tried as far as possible to reconstruct the atmosphere in which the Ginsburgs wrote their letters. To this end, my comments following each letter provide perspective not only on the changing relationships within the family but, most specifically, on the changing course of the War, as it affected the region in which they lived. I have described military developments in the entire North Caucasus, which would have been of significance to the Ginsburgs, if they had known about them in real time, but which they may or may not have learned about from the Soviet media.

To provide a further perspective on the outlook of the Ginsburgs, I have interwoven their correspondence with other contemporary testimonies relating to this period. Although, in many cases, it cannot be established whether the Ginsburgs shared some or all of these views, these documents provide an important additional context. To this effect, I have also cited relevant secondary sources that were published between June 1941 and July 1942 in Rostov-on-Don and other North Caucasian cities to which Jews were evacuated. These sources include the central Soviet newspapers (Pravda and Izvestiya) largely available in Rostov-on-Don, as well the local Soviet newspapers published in the North Caucasus, most specifically the newspaper Molot (Hammer), which was printed in Rostov-on-Don.19

In an attempt to understand how the Ginsburgs’ perception of the events was shaped, I have also included other Soviet sources, indicating whether or not they would have been available to the Ginsburgs. Furthermore, in an attempt to present a relatively accurate appraisal of the strategic situation in the region, I have included contemporary articles from The New York Times and The Washington Post, expanding on the course of the War in the Caucasus. In many cases, these articles present a critical reading of Soviet and German military communiques, a unique and largely forgotten source of information on the course of the War. I recognized their value as a real-time source, even if they were not available to the Ginsburgs. To obtain a real-time update on the military situation in the region), first I had to strip off the layers of propaganda; I have commented on these communiques, as well as on all the other sources cited in the book.

In selecting which sources to include, I have given priority to the local media, assuming that, as a rule, the local population, including members of the Ginsburg family, were primarily interested in the news about their own locality. Furthermore, in many cases, the news from official Soviet newspapers did not reach them. Consequently, I have chosen local news (such as a report concerning fighting in the Rostov theatre) and major news from other sectors (such as a successful Soviet advance in some region other than the southern Soviet-German front). By the same logic, among publications from outside the Caucasus, I have selected only those that were of paramount importance in promoting Jewish awareness of the extensity of the German threat.

Where I have added information in the letters, for clarification purposes, I have used square brackets and italics. The word “Note” has been used where it refers to an official announcement by the Soviet authorities. The word “War,” on its own, has been capitalized whenever it refers to the Soviet-German War. Other references to war, such as “wartime” and “time of war,” are not capitalized.

As regards names, where the married name of the sisters is known (in the case of Anya and Liza), I have given both their married name and maiden name (in parenthesis) throughout chapter 1.1 and the first time that one of them is mentioned in the other chapters, and only used their maiden name (Ginsburg) thereafter. For all three sisters, I have given their formal first names followed by their diminutive names (in parenthesis) throughout chapter 1.1 and the first time that they are mentioned in the other chapters, and only used their diminutive names thereafter. However, where their names are mentioned in the footnotes, I have used “Liza Chazkewitz and Anya Greener,” as their letters to Efim are referenced in this way at Yad Vashem.

1 See, for example, Tat′iana Voronina, “Kak chitat′ pis′ma s fronta? Lichnaia korrespondentsiia i pamiat′ o Vtoroi mirovoi voine,” Neprikosnovennyi zapas 3 (2011): 162.

2 For example: Robert Kindler, “Famines and Political Communication in Stalinism. Possibilities and Limits of the Sayable,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 62, no. 2 (2014): 255–272.

3 For example, Malte Griesse, Communiquer, juger et agir sous Staline. La personne prise entre ses liens avec les proches et son rapport au système politico-idéologique (Frankfurt a.M. [et al.]: Lang, 2011).

4 In this book, the terms “refugee” and “evacuee” are used interchangeably to denote all those Jews and non-Jews who moved out of the threatened Soviet regions, whether under a government-initiated program or independently, unless stated otherwise. By the same token, the terms “evacuation,” “flight” and “escape” are also used interchangeably to describe the ways in which people moved out of the threatened Soviet regions, whether under a government-initiated program or on their own, unless stated otherwise.

5 Karel C. Berkhoff, Motherland in Danger: Soviet Propaganda during World War II (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 134–166.

6 On Soviet newspapers in the 1920s, that is, during the stage framing this perception, see Matthew Lenoe, Closer to the Masses: Stalinist Culture, Social Revolution, and Soviet Newspapers (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

7 The emphasis here is on the words “relatively stable” and “some.” This does not mean that political and moral considerations in their deliberations were entirely non-existent. But several hundred testimonies, analyzed in my book (Kiril Feferman, The Holocaust in the Crimea and the North Caucasus [Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2016]), roughly half of them pertaining to the Caucasus, point to the overwhelming importance of economic factors when the Jews were discussing their motives for evacuation from this region.

8 Anna Shternshis, “Between Life and Death: Why Some Soviet Jews Decided to Leave and Others to Stay in 1941,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 15, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 478–479.

9 For example, Mordechai Altshuler, “The Distress of Jews in the Soviet Union in the Wake of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact,” Yad Vashem Studies 36, no. 2 (2008): 85–88.

10 Unfortunately, the archives in Rostov and Moscow can only provide fragmentary material, inadequate for establishing the dimensions not only which share of the evacuees the Jews constituted (comparing the relative number of Jews and non-Jews in the local population), but also of the general evacuation program in the city. It seems likely that most records were destroyed or lost during the two occupations of Rostov-on-Don.

11 Scholarship on this topic is rapidly expanding. See, for example, Arkadi Zeltser, “How the Jewish Intelligentsia Created the Jewishness of the Jewish Hero,” in Soviet Jews in World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering, ed. Harriet Murav and Gennady Estraikh (Boston, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2014), 104–129. Cf. David Shneer, Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011).

12 Vladimir L. Piankevich, “The Family under Siege: Leningrad, 1941–1944,” The Russian Review 75 (2016): 107–137.

13 For example, Albert Kaganovich, “Jewish Refugees and Soviet Authorities during World War II,” Yad Vashem Studies 38, no. 2 (2010): 85–121. Cf. Vadim Dubson, “On the Problem of the Evacuation of Soviet Jews in 1941 (New Archival Sources),” Jews in Eastern Europe 3, no. 40 (1999): 37–56.

14 For example, Albert Kaganovich, “Evreiskie bezhentsy v Kazakhstane vo vremia Vtoroi Mirovoi voiny,” in Alexander Baron (ed.), Istoriia, pamiat′, liudi. Materialy V mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii (Almaty: Assotsiatsiia “Mitsva,” 2011), 13–31. Cf. Zeev Levin, “Antisemitism and the Jewish Refugees in Soviet Kirgizia, 1942,” Jews in Russia and Eastern Europe 1 (2003), 191–203.

15 The notable exception is Shternshis, “Between Life and Death,” 477–504.

16 On the Bolshevik policies in housing question before the war, see Steven E. Harris, Communism on Tomorrow Street: Mass Housing and Everyday Life after Stalin (Baltimore, MD: The Woodrow Wilson Center Press and the Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 45–47, 49–52, 55–70.

17 We can only speculate on why this movement of evacuees into the North Caucasus happened: for example, none of the Ginsburg respondents observed this movement (highly unlikely), or they did not deem it worth mentioning in their letters (more plausible).

18 On this issue, see Christina Winkler, “Rostov-on-Don 1942: A Little-Known Chapter of the Holocaust,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 30, no. 1 (2016): 105–130.

19 For a brief overview of the Soviet newspapers during the War, see S. V. Shpakovskaia, “Sovetskie gazety v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny,” Voprosy istorii 5 (2014): 64–74.