Читать книгу “If we had wings we would fly to you” - Kiril Feferman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

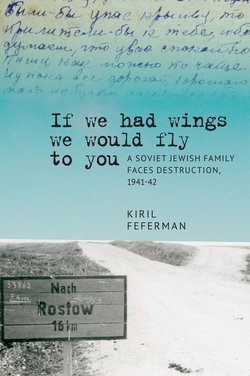

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1.1

The Ginsburg Family in the North Caucasus

The Ginsburg family came originally from Odessa, which was probably the most important trading center of the Russian Empire and a major harbor on the Black Sea. Home to more than 125,000 Jews in 1897, the city was a flourishing center of Jewish economic life from the second half of the nineteenth century.1 However, it was also a difficult place for many Jews to live in; most of them could only eke out a miserable existence in the city as small-time traders, shopkeepers, and workshop employers.2 They faced vigorous competition with one another—every third inhabitant of Odessa was Jewish—and with non-Jews.

The new generation of the Ginsburgs: the sisters Manya (Monya), Anna (Anya), Elizaveta (Liza), and their brother Efim, were born in Odessa between 1890 and 1897. It is likely that their parents (father Gedaliya and mother Hanna-Rachel) were frustrated by the tough competition and the need to provide for their growing family. It is also likely that they were scared into leaving Odessa, especially after the pogrom that broke out in the city in October 1905, which led to the murder of some 400 Jews—the bloodiest pogrom in the Russian Empire up to that point.3 As a result, Gedaliya and Hanna-Rachel took their four children and left Odessa, somewhere before 1912, probably soon after the pogrom.

The Ginsburgs chose to move to the city of Rostov-on-Don, situated only 800 km to the east of Odessa, where they managed to survive the turbulent years of World War I and the Russian Civil War. When they arrived in Rostov-on-Don, it already had a substantial Jewish population. The city, founded in 1749, had its own distinct history, including the history of its Jewish residents. It was a part of what we refer to today as the “North Caucasus,” all of which now belongs to the Russian Federation. The region first came under the sway of the Russian Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Russian penetration into these territories was met with occasional fierce armed resistance by the local inhabitants.4 Still, the Empire prevailed, and from the early 1860s onwards, the region was subdued.5

The settlement of Ashkenazi Jews in most of the North Caucasus region was generally prohibited, as the area was situated outside the Pale of Settlement.6 The only exceptions were the cities of Rostov-on-Don and Taganrog, which, until 1887, were part of the Ekaterinoslav guberniya (province), and thus part of the Pale. The first reference to a Jewish presence in the North Caucasus can be traced back to 1800, when ten Jewish meshchane (petty bourgeois) were registered as residents of the Rostov uezd (area).7 As the Russian penetration into the region brought peace and prospects for economic development, Jews began to flock to the North Caucasus. Their prospects were doubtless better in these territories than in the overcrowded Pale of Settlement. As of 1838, some 6,000 Jews were registered in the Ekaterinoslav province, constituting 0.59% of the total population. According to another source, 26,069 Jews were living in the province in 1864.8 In the same year, there were 289 Jews living in the city of Rostov-on-Don (3.1% of the total population). There were also Jews among the soldiers and kantonisty stationed in the Dimitri Rostovski fortress.9 Rostov-on-Don continued to attract Jews, and by 1866, their numbers had reached 2,500, almost 6% of the total population of the city.10 One of the most important Russian Jewish industrialists and bankers, Samuil Polyakov, was active in the area from the late 1860s onwards.11

Towards the end of Alexander II’s reign, the Tsarist government attempted to put an end to the semi-legal Jewish presence in the province. On May 22, 1880, the “Caucasian” parts of the guberniya were given to Oblast' voiska Donskogo (the Province of the Don Cossack Host), where Jews were explicitly banned from living and owning property. The new law was rigorously enforced, and all the Jews living in the region (which roughly includes the present-day Rostov district) with the exception of the two big cities, Rostov-on-Don and Taganrog, were expelled and sent back to the Pale of Settlement.12

The Tsarist government endeavoured to complete the expulsion of the Jews in 1887, when the area around Rostov-on-Don and Taganrog and the cities themselves were annexed by the Province of the Don Cossack Host. As a result, the residence and property ban was extended to include the Jews living in the two cities. Up to 10,000 Rostov Jews were due to be deported, but the decree was suspended after the Rostov City Council petitioned for its reversal on the grounds that it would be detrimental to the development of trade.13

The only population census conducted in the Russian Empire, in 1897, revealed the following statistical data regarding the presence of Jews (including Mountain Jews)14 in the North Caucasus: there were 15,978 Jews in the Province of the Don Cossack Host, 2,196 in the area of the Kuban Cossackdom, and 6,582 in the area of the Terek Cossackdom.15

According to the Russian population census of 1897, among all other nationalities registered in Rostov-on-Don, the Jews had the highest level of literacy for men (71.7%) and one of the highest for women (54.7%). Unlike in other parts of the Empire, in the city of Rostov-on-Don relatively many who professed Judaism declared that Yiddish was not their mother tongue. This was due to the presence of many Mountain Jews.16

The North Caucasian Jews led an intensive religious and social life. In 1864, the local authorities recorded the presence of eleven synagogues and twenty-four prayer houses in the Ekaterinoslav province.17 In the city of Rostov-on-Don, a soldiers’ synagogue was opened in 1872, and the main synagogue was also inaugurated at that time.18 In the 1880s, a Jewish hospital was opened in Rostov-on-Don.19 By the end of the nineteenth century, the Rostov Jewish community could boast several Talmudei Torah (Jewish primary schools), a Jewish public college for girls, and a Jewish college acting under the auspices of the synagogue.20

As elsewhere in the Russian Empire, many of the younger generation of Rostov Jews became dissatisfied with the Tsarist regime, and joined the ranks of the revolutionaries.21 In the second half of October 1905, a pogrom occurred in Rostov-on-Don, which also involved clashes between the Black Hundreds22 and revolutionary-minded workers and young people. Some 150 Jews were slaughtered in the pogrom, which made it the second bloodiest pogrom in the Russian Empire (after Odessa) before the Russian Civil war.23

The next landmark in the history of Rostov Jewry was the arrival in the city of the fifth Lubavicher Rabbi, Rabbi Sholom Dov-Ber Schneerson, in 1915.24 He spent five years there, until he passed away in 1920.

Contrary to what occurred in many other parts of the former Russian Empire, after the Bolshevik revolution in November 1917, the sympathies of at least the more prosperous local Jews were with the White Russians. On December 13, 1917, A. Alperin, an important local merchant, delivered 800,000 rubles that had been collected by Rostov Jews to the Ataman of the Province of the Don Cossack Host for the fight against the Bolsheviks.25

In the course of the Russian Civil war in 1917–1920, the Jewish population in the North Caucasus found itself largely under the control of the White Russian movement. It is well known that a considerable number of White Russian troops espoused strong anti-Semitic feelings (see further on). In spite of this, in the North Caucasus the situation remained under control, obviously because of the relatively strong rule of the White administration, and there were no reports of significant anti-Jewish excesses there.26 For some months, in the second half of 1918, part of the region, including the city of Rostov-on-Don, was occupied by the German army.27 On the whole, under White Russian rule, independent internal Jewish life continued during these years, with a particular rise in Zionist activities.28

With the advent of the Bolsheviks, anti-Semitism in the region did not disappear but largely went underground.29 Nevertheless, the infrequent reports published in a Rostov newspaper in 1929 depict vicious verbal attacks by local workers, who lashed out at their Jewish colleagues at the city’s plants.30 Still, the Jewish population in the region grew slightly in the period between the two World Wars, attracted by growing economic prospects and relatively plentiful food,31 an important factor in the Soviet Union at that time. On the eve of the Soviet-German War, the small Jewish population was concentrated in several large North Caucasian cities, with Rostov-on-Don having by far the largest Jewish population in the region. According to the 1939 Soviet population census, 27,039 Jews (5.3% of the total population) lived in Rostov-on-Don,32 while 33,024 Jews (1.1% of the total) lived in the whole Rostov District.33 In addition, 4,600 Jews were registered in Kabardino-Balkaria, 2,100 in North Ossetia, 7,600 in the Krasnodar territory, and 7,100 in the Stavropol territory.34

The region was noteworthy for its unique Cossack population, well known for its anti-Semitic mindset. The Cossacks participated in the deportation of Jews by the Tsarist army during World War I,35 and were actively involved in the pogroms in Ukraine, for example, in 1919.36 The Bolshevik anti-Cossack crusade37 (likely associated, one way or another, with the Jews, in the eyes of the local people in the region), included the Bolshevik onslaught on the Cossacks during the Collectivization period (presided over by Lazar Kaganovich, the only Jewish member of Stalin’s inner circle).38 The continuing anti-Semitic sentiment inculcated in the local people was latent, as it had almost no way to express itself, before the Germans occupied parts of the region. But it was significant, judging by the noticeable number of active collaborators and quiet denouncers in the North Caucasus during the German occupation.39 It was not all-encompassing, however, as evidenced by some manifestations of sympathy towards the Jews under Soviet rule before the German occupation in 1941–1942, and especially during the occupation.40

Finally, we should mention that the oppressive Soviet policies adversely affected the whole population of the North Caucasus, as they did the rest of the country. During the 1930s, some 42,000 Russian civilians were “repressed” (to adopt the Soviet term), that is, either shot down or incarcerated in the Azov-Chernomorsk territory (an administrative unit with the capital in Rostovon-Don, which existed from 1934 to 1938).41 The Cossacks, the Bolsheviks’ bitter enemies during the Russian Civil war, suffered particularly as a result of these policies.42 It is suggested that these policies affected local Jews, in a similar way to the rest of the population, but no worse.43

During the 1920s and the 1930s, most members of the Ginsburg family continued to live in Rostov-on-Don. It seems that following their relocation to a considerably more Russian and less Jewish city than Odessa, father Gedaliya changed his first name to Grigory, probably in order to improve his standing with his customers. But his wife kept her Jewish-sounding name, probably because she did not work outside of their home. However, we cannot rule out that this behavior also reflected the different attitude of the husband and wife to assimilation. Presumably they died in the 1920s or the 1930s, but we do not know when or how they died, for the correspondence does not mention them even once.

The only family member who was not living in Rostov-on-Don at the end of the 1930s was the youngest brother, Efim Ginsburg (1897–1973). The brother of the three aunts, he received almost every letter in this collection and managed to keep them in his possession during and after World War II.

Efim Ginsburg. 1930s. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archive.

His road from Rostov-on-Don to Moscow had been a very tortuous one. In 1921, Efim Ginsburg was imprisoned by the Soviet authorities on account of his “belonging to a socialist party,”44 as recorded in the database compiled by the Russian “Memorial” society. If we try to interpret this meager information, it seems most plausible that Efim Ginsburg (who turned twenty in 1917) had been affiliated with one of the Russian socialist parties (but not with the Bolsheviks or with Jewish Socialist parties) even before 1917. I assume that most likely he was a member of the Menshevik faction,45 or a Socialist Revolutionary party with their particularly high number of Jewish followers. This would account for his persecution by the authorities as early as 1921, that is, immediately after the Bolsheviks managed to consolidate their rule in Rostov-on-Don, at the end of the Civil War.

Unfortunately, there is almost no information about Efim Ginsburg’s life between 1927, when he was released from prison, and late 1939, when he resurfaced in the Ginsburg correspondence.46 So all we can do is to try to conjecture how he spent those years. The likelihood that the Soviet security agencies would have left him alone and that he was not hounded or discriminated against in that period would seem low. It is highly unlikely that Efim Ginsburg’s socialist past would have been entirely erased from police records.47 Formally, the rights of all those suffering from legal disenfranchisement were reinstated according to the 1936 “Stalin” Constitution.48 But, in fact, people with such backgrounds were the first on the list of those targeted by the largest wave of the Big Terror in 1937–1938, and the odds were high that Efim Ginsburg would not have survived.

Yet he did survive, and this begs for an explanation. There were some, albeit minor, exceptions to the aforementioned trends in the Soviet policies. Some members of Socialist parties were able to change their banners and join the victorious Bolshevik regime. One of the most prominent examples is Andrei Vyshynsky, who, in 1917, as a minor official, signed the Provisional Government order to arrest Lenin. He formally switched allegiance from the Menshevik party to the Bolsheviks only in 1920, but was, nevertheless, able to rise to prominence in the Soviet Union, becoming a Chief Prosecutor in 1935–1939 and the Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1949–1953. Certainly even Vyshinsky knew that such a stain on his reputation could never be entirely removed. Presumably, this was the reason why he was particularly compliant in his dealings with the Soviet leaders, especially the security chiefs.49

In Efim Ginsburg’s case, whatever his path during these turbulent years, by the end of 1939 (when he received the first letter from his family), he was living legally in Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union, which indicates that all previous charges against him had been formally dropped by that time. And yet, it seems obvious that he spent those years in constant fear, as did his family. This would account for the fact that, when the correspondence began, Efim Ginsburg was living separately from the rest of the family and probably had not communicated with them for many years. It may be the reason why the first letter in the correspondence (not analyzed in this book) was sent in late December 1939,50 the year when the wave of terror after the Great Purges subsided.51 Possibly, the Ginsburgs had decided that conducting a correspondence would no longer jeopardize the Rostov branch of the family, especially Volodya Meerovich, the highest-ranking member of the clan.

The fact that Efim (and, in a wider sense, the entire Ginsburg family) belonged to the circle of those oppressed by the Stalin regime certainly sheds a special light on the correspondence. By all accounts, the family members were predisposed to be particularly cautious in putting their “deviationist” (that is, different from the officially approved) thoughts down on paper, to a greater extent than ordinary Soviet people. It is a big question, whether and to what extent their experience was so unique, given the vast number of people who suffered from Stalinist repression.52 But in any case, it adds an additional and extremely important layer to the considerations of the Ginsburg family members as to whether they should flee or not, and what to include or avoid mentioning in their letters.

We do not have any information about Efims’s profession. The letters only allude to his important position and his being appreciated by his superiors (at least, in the eyes of his sisters). As the correspondence never mentions his wife or children, it seems most likely that he was not married and had no children at the time of the Soviet-German War. It indeed looks plausible, given his apparently turbulent prewar years. In July 1941, he was evacuated from Moscow to Omsk.53 Then he was evacuated for a second time, from Omsk to Alma-Ata (now Almaty in Kazakhstan).54 The sad irony is that, since he did not die in the Holocaust, there was no one who could submit any information about him, apart from several small biographical details released by his widow, Ida, in the file submitted to Yad Vashem in 1989.

Towards the end of the Soviet-German War, Efim Ginsburg returned to Moscow. He married Ida Markovna Dektor sometime after 1943. Ida was a philologist, speech therapist, and translator. She taught at the Institute of Literature. The only thing we know about Efim’s postwar pursuits is that in the 1960s “he wrote books on technical issues.”55 In 1973, only ten days after the end of the Yom Kippur War, the couple left the Soviet Union and immigrated to Israel. According to a handwritten note added by Ida Ginsburg-Dektor to one of the Ginsburg letters, he was granted special permission to take the entire correspondence with him abroad,56 which was an unusually big concession for the Soviet authorities to make. The couple made their home in the city of Ramat Gan, where Efim died in 1973, only two months after arriving in Israel. His widow donated the vast correspondence that he had conducted with those members of the Ginsburg family who were murdered during the Holocaust to the Yad Vashem Archives in Jerusalem, in 1989. All my attempts to find Ida or any children they might have had, or any other member of his family have proved futile.

At the start of the Soviet-German War, the Rostov branch of the family numbered ten people, was made up of three generations. Among the adults, there were five women and three men, one of whom died a natural death in the fall of 1941. There were also two children in the family. The older generation was represented by three sisters. (The information about their husbands is also presented in this study.)57 As can be seen from their correspondence, the three sisters thought of themselves as elderly, although by modern standards they were only middle-aged. This was because life expectancy in Soviet Russia was much lower than what is customary today in the developed world. In 1939, it was 49.7 years for women and 44.0 for men.58

1) Manya (Monya) (née Ginsburg) was born in Odessa in 1890 to Gedalia and Hanna-Rachel; she was married to Pinchas (Pinya). She was Tamara Meerovich’s mother. She was murdered by the Germans in the Rostov District in August 1942.

Monya was the oldest family member. (We do not know her married name, so for the purposes of our book we will also refer to her as a Ginsburg, which was certainly her maiden name). She was not employed in 1941–1942, and mainly kept herself busy looking after her grandson, Grisha. She didn’t take part in the correspondence with Efim.

2) Anna (Anya) Greener (née Ginsburg) was born in Odessa in 1893 to Gedalia and Hanna-Rachel; she married Avraham Greener (1890–1942),59 also from Odessa. They had one daughter, Tsylya, who married David Pinchos, and one granddaughter, Anya.

Anya Greener. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

Anya, the second sister, was sluzhashchaia (“functionaire” or “employee,” in Soviet parlance). During 1941–1942, she did not work and was mainly in charge of the house and of buying food for the family. Anya almost never signed the letters sent to Efim, but her sister Liza, who appears as the principal correspondent from this part of the family, repeatedly emphasized that the letters were written by both sisters. She was murdered in the Rostov District in August 1942.

3) Elizaveta (Liza) Chazkewitz (née Ginsburg) was born in Odessa in 1895 to Gedalia and Hanna-Rachel; she married Boris Chazkewitz, and worked as a pharmacist.

Elizaveta (Liza) Chazkewitz. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

Liza, the third sister, had no children. She had a profession, pharmacist, with which she could earn her living and even support her sister Anya, and sometimes even other members of the family. Liza was very actively involved in the correspondence. From the letters, it is clear that she always acted together with her older sister Anya, which gave them a high standing in the interfamilial relationship. She was murdered in the Rostov District in August 1942.

4) Boris Chazkewitz, born in 1893, was married to Liza Ginsburg; he died in Rostov-on-Don in September 1941.

Boris Chazkewitz. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

Although he signed one letter, together with his wife, we know nothing about him, except for the fact that his health deteriorated dramatically in late summer 1941. He had to go on working, despite his illness. He died of natural causes on September 18, 1941, that is, two months before the first German occupation of Rostov-on-Don.

Anya and Liza were not evacuated from Rostov-on-Don in 1941; they survived the first German occupation of the city (November 21–28, 1941). They remained in Rostov-on-Don until July 1942, when the entire family moved to the village of Rogovskoe in the Rostov District, situated more than a hundred kilometers from the city. They were murdered there, after the Germans occupied the area in August 1942.

The younger generation was represented by the Meerovich and Pinchos families.

5) Tamara Meerovich was born 1913 in Rostov-on-Don to Pinya and Monya. She was married to Vladimir (Volodya) Meerovich and was the mother of Grisha. Tamara worked as a book-keeper.

Tamara Meerovich. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

Tamara was actively involved in the correspondence, after she was evacuated from Rostov-on-Don in October 1941 together with her mother and son and the Pinchos family, first to the town of Budennovsk in the neighboring Krasnodar territory, and then, in late December 1941, to the slightly more remote city of Ordzhonikidze (now called Vladikavkaz), the capital of the Autonomous Republic of North Ossetia. Prior to her departure, it seems that she decided that the letters sent by Efim Ginsburg’s sisters, Anya and Lisa, reflected her own point of view well enough or—this seems to be more likely—she did not wish to publicly voice her disagreement with her aunts, in order not to upset her uncle Efim.

Tamara was employed and was able to provide for her family. She stayed in Ordzhonikidze until early June 1942, when she returned to Rostov-on-Don. She was murdered, with the rest of her family, in August 1942, in the village of Rogovskoe in the Rostov District.

6) Vladimir (Volodya) Meerovich, date of birth unknown. Volodya was married to Tamara Meerovich and was the father of Grisha.

Vladimir Meerovich, Tamara, and their son Grisha. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

Volodya was employed in a relatively important position in one of Rostov’s plants, and was probably a member of the Bolshevik Party. In November 1941, he defended Rostov-on-Don fighting in the ranks of the so-called “Extermination Battalion.”60 Then he was evacuated, together with his plant, to the nearby city of Ordzhonikidze. In early March 1942, Volodya and his plant were evacuated back to Rostov-on-Don. On April 21, he was conscripted into the Red Army. His last letters show that he was still alive in April 1943. He received information about the fate of his family before he was killed in action against the Germans in mid-1943, apparently intent on avenging their murder.

The Pinchos family consisted of:

7) David (Dod or Doda), born in Rostov-on-Don in 1912, was an “employee” (sluzhashchii). He was married to Tsylya Pinchos and was the father of Anya.

David Pinchos. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

David served in the Red Army from fall 1941 to spring 1942. He was released from the Army in spring 1942 due to his very poor health. He returned to his family in Rostov-on-Don and was murdered with the others in the Rostov District in August 1942. He was not involved in the correspondence.

8) Tsylya, born in Rostov-on-Don in 1914 to Avraham and Anya Greener, was married to David Pinchos, and was the mother of Anya.

Tsylya Pinchos. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

Tsylya seems to have had no formal profession, but took occasional side jobs as a tutor. She was evacuated with her daughter, together with the Meerovich family, first to Budennovsk, and then to Ordzhonikidze. She returned to Rostov-on-Don in early March, 1942. She was murdered in the village of Rogovskoe in the Rostov District in August 1942.

The youngest generation consisted of the two Meerovich and Pinchos children.

9) Grigory (his formal name, which the family never used. He was usually called Grisha) Meerovich was born in 1936 in Rostov-on-Don and murdered in the Rostov District in August 1942.

10) Anna (her formal name, which the family never used. She was usually called Anya, or Anechka) Pinchos was born in Rostov-on-Don in 1935, and was murdered in the Rostov District in August 1942.

Ania Pinchos. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Hall of Names.

On October 13, 1941, several days before the Germans seized Rostov-on-Don, Tamara Meerovich, her son Grisha, mother Monya, and her cousin Tsylya Pinchos with her daughter Anya were evacuated from the city by train to Budennovsk in the Ordzhonikidze District, situated some 580 km to the south-east of Rostov-on-Don.

In the first half of 1942, the two evacuee branches of the family returned to Rostov-on-Don. In March 1942, Tsylya Pinchos was the first to go back, with her daughter Anya. On June 2, 1942, Tamara Meerovich, with her son and her mother, returned to Rostov-on-Don from Ordzhonikidze. In the first half of July, they moved to the village of Rogovskoe in the Rostov District. They were murdered there during the German occupation in August 1942.

Grisha Meerovich and Anya Pinchos, 1936–1937. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archive.

1 On the general history of the Jews in Odessa, see Steven J. Zipperstein, The Jews of Odessa: A Cultural History (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1985).

2 Jarrod Tanny, City of Rogues and Schnorrers: Russia’s Jews and the Myth of Old Odessa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 30.

3 On this pogrom and more generally on the strained relationship between Jews and non-Jews in Odessa in the years preceding the pogrom, see Caroline Humphrey, “Odessa: Pogrom in a Cosmopolitan City,” Ab Imperio 4 (2010): 27–79.

4 See, for example, Firouzeh Mostashari, On the Religious Frontier: Tsarist Russia and Islam in the Caucasus (London: Tauris, 2006); Russian-Muslim Confrontation in the Caucasus: Alternative Visions of the Conflict between Imam Shamil and the Russians, 1830–1859, ed. Thomas Sanders, Ernest Tucker, and Gary Hamburg (London: Routledge Curzon, 2004).

5 For example, Timothy K. Blauvelt, “Military-Civil Administration and Islam in the North Caucasus, 1858–1883,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 11, no. 2 (Spring 2010): 221–255.

6 The Pale of Settlement was the area where Ashkenazi Jews were specifically permitted to live in the Russian Empire. Non-Ashkenazi Mountain Jews, who were regarded by the Imperial authorities as native peoples (gortsy), were permitted to live in the North Caucasus region, where they generally did not face the restrictions applied to Ashkenazi Jews. However, after 1887 Mountain Jews also experienced a deterioration in their standing. Ekaterina Norkina, “The Origins of Anti-Jewish Policy in the Cossack Regions of the Russian Empire, Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century,” East European Jewish Affairs 43, no. 1 (2013): 62–76.

7 Mikhail Gontmakher, Evrei na donskoi zemle. Istoriia, fakty, biografiia (Rostov-na-Donu: RostIzdat, 1999), 20.

8 Ibid., 20–21.

9 Ibid., 22.

10 Ibid., 23.

11 Ibid., 25–28.

12 Ibid., 29–31.

13 Ibid., 41–42.

14 The Mountain Jews were a small ethnic group, originally made up of Persian Jews, but much influenced by the surrounding peoples of the Caucasus region. See, for example, Sasha S. Goluboff, “‘Are They Jews or Asians?’ A Cautionary Tale about Mountain Jewish Ethnography,” Slavic Review 63, no. 1 (2004), 113–140.

15 Sergei Markedonov, “Evrei v oblasti voiska Donskogo v kontse 19—nachale 20 veka,” in Trudy Vtoroi molodezhnoi konferentsii SNG po iudaike—“Tirosh” (Moscow: Sefer, 1998), http://www.jewish-heritage.org/jr2a18r.htm, accessed November 30, 2011.

16 Gontmakher, Evrei na donskoi zemle, 59–61.

17 Ibid., 20–21.

18 Ibid., 23.

19 Ibid., 38–39.

20 Ibid., 49.

21 Ibid., 55–56, 75–76.

22 The Black Hundreds (in Russian—Chernaia sotnia) was a vaguely defined Russian nationalist movement that started during the First Russian Revolution (1905–1907). It was vociferously anti-Semitic, and its members took an active part in pogroms against the Jews. On this movement, see Walter Laqueur, Black Hundred: The Rise of The Extreme Right in Russia (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1993).

23 Ibid., 109–111.

24 Andrew N. Koss, “War Within, War Without: Russian Refugee Rabbis during World War I,” AJS Review 34, no. 2 (2010): 239–240.

25 Kratkaia Evreiskaia Entsiklopediia (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1994), vol. 7, 402–404.

26 Markedonov, “Evrei v oblasti voiska Donskogo.”

27 It seems that from the Jewish perspective, the German occupation of the region in 1918 brought about calm and relief from pogroms or from fear of pogroms. On the military aspects of the German drive to the region, see Reinhard Nachtigal, “Krasnyj Desant: Das Gefecht an der Mius-Bucht. Ein unbeachtetes Kapitel der deutschen Besetzung Südrußlands 1918,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 53, no. 2 (2005): 221–246.

28 Oleg Budnitskii, “Evrei Rostova-na-Donu na perelome epokh (1917–1920),” in Rossiiskii sionizm: istoriia i kul′tura (Moscow: Evreiskoe agentstvo v Rossii, SEFER, Dom evreiskoi knigi, 2002). Cf. Oleg Budnitski, “The Jews in Rostov-on-Don in 1918–1919,” Jews and Jewish Topics in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe 3, no. 19 (1992): 16–29.

29 On one of the few examples of an open manifestation of anti-Jewish sentiments (directed against Mountain Jews), see Lyudmila Gatagova, “Caucasian Phobias and the Rise of Antisemitism in the North Caucasus in the 1920s,” The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 36 (2009): 42–57.

30 “Na bor′bu s antisemitizmom,” Molot (Rostov-on-Don), December 14, 1928 and January 16, 1929. Quoted in: Gontmakher, Evrei na donskoi zemle, 167–168.

31 The emphasis here is on the word “relatively.” Soviet famine in the 1930s also struck at the North Caucasus, albeit arguably on a lower scale than elsewhere in the country. Brian J. Boeck, “Complicating the National Interpretation of the Famine: Reexamining the Case of Kuban,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 30, no. 1/4 (2008): 31–48. Cf. Andrea Graziosi and Dominique Négrel, “‘Lettres de Kharkov’: La famine en Ukraine et dans le Caucase du Nord à travers les rapports des diplomates italiens, 1932–1934,” Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique 30, nos. 1–2 (Janvier–Juin 1989): 5–106.

32 Vsesoiuznaia perepis′ naseleniia 1939 goda. Osnovnye itogi (Moscow: Nauka, 1992), 24, 26. According to German sources, in Rostov there lived from 200,000 to 300,000 civilians. Andrej Angrick, Besatzungspolitik und Massenmord. Die Einsatzgruppen D in der südlichen Sowjetunion, 1941–1943 (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2003), 561.

33 Evgenii Movshovich, “11 avgusta—60 let tragedii v Zmievskoi balke,” Shma (Rostov-na-Donu) 7, no. 36 (May 15–July 24, 2002): 3. Cf. Vladimir Kabuzan, Naselenie Severnogo Kavkaza v 19–20 vekakh: etnostatisticheskoe issledovanie (St. Petersburg: Izd-vo “Russko-Baltiiskii informatsionnyi tsentr BLITS,” 1996), 209.

34 Including Mountain Jews. Distribution of the Jewish Population of the USSR 1939, ed. Mordechai Altshuler (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, Center for the Research of East European Jewry, 1993), 13–15.

35 John Klier [as Dzhon Klir], “‘Kazaki i pogromy’: Chem otlichalis′ voennye pogromy,” in Mirovoi krizis 1914–1920 gg. i sud′ba vostochnoevropeiskogo evreistva, ed. Oleg Budnitskii (Moscow: ROSPEN, 2005), 55–56, 59–60.

36 Peter Kenez, Civil War in South Russia, 1919–1920. The Defeat of the Whites (Berkeley: University of California, 1977), 172. Cf. Iosif Shekhtman, Pogromy Dobrovol′cheskoi Armii na Ukraine: K istorii antisemitizma na Ukraine v 1919–1920 gg. (Berlin: Ostjüdisches Historisches Archiv, 1932), 31, 76.

37 Elena Khachemizova, Obshestvo i vlast′ v 30-e—40-e gody XX veka: Politika repressii (na materialakh Krasnodarskogo kraia), PhD diss., Maikop, Adygeiskii gosudarstvennyi universitet, 2004, 44–107.

38 E. A. Rees, Iron Lazar: A Political Biography of Lazar Kaganovich (London: Anthem Press: 2012), 110–111, 113, 121.

39 Feferman, The Holocaust in the Crimea, 427–435.

40 Ibid., 438–441.

41 Evgenii Zhuravlev, Kollaboratsionizm na iuge Rossii v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny (1941–1945 gg.) (Rostov-on-Don: Izd-vo Rostovskogo universiteta, 2006), 22–27, 42.

42 Natal′ia Bulgakova, Sel′skoe naselenie Stavropol′ia vo vtoroi polovine 20-kh—nachale 30-kh godov 20 veka: Izmeneniia v demograficheskom, khoziaistvennom i kul′turnom oblike, PhD diss., Stavropol, Stavropol′skii gosudarstvennyi universitet, 2003, 17–18.

43 Dissertations written in the North Caucasus by local researchers do not mention a noticeable Jewish presence among the regional power elites in the 1930s. Aleksandr Savochkin, Massovye repressii 30–40-kh gg. 20 v. na Severnom Kavkaze kak sposob utverzhdeniia i podderzhaniia iskliuchitel′noi samostoiatel′nosti gosudarstva, PhD diss., Vladimir, Vladimirskii iuridicheskii institut Federal′noi sluzhby ispolneniia nakazanii, 2008. Cf. Khachemizova, Obshestvo i vlast′.

44 I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer of this book for providing me with the clue as to where to search for Efim Ginsburg’s background during the prewar period. I contacted the Russian “Memorial” society, which gathers information on former members of Socialist parties in Russia. They had a couple of lines devoted to Efim Ginsburg and finally they were able to confirm that indeed we were talking about the same person.

45 On the Menshevik path in the Russian Revolution, see, for example, Abraham Ascher, “The Mensheviks in the Russian Revolution,” Zmanim: A Historical Quarterly 27/28 (1988): 38–53 [Hebrew]. On the Socialist Revolutionaries, see, for example, Marc Jansen, A Show Trial under Lenin: The Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries, Moscow, 1922 (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1982).

46 The only exception is few photos dating 1932 and 1936, which either featured Efim or were addressed to him.

47 David R. Shearer, Policing Stalin’s Socialism: Repression and Social Order in the Soviet Union, 1924–1953 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), especially pp. 158–180.

48 Golfo Alexopoulos, Stalin’s outcasts: Aliens, citizens, and the Soviet state, 1926–1936 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003), 170–174. Disenfranchisement in the Soviet Union entailed a ban on participation in elections. It also meant receiving a reduced amount of food coupons, or not receiving them at all, a ban on certain types of employment, etc.

49 Valentin Berezhkov, Kak ia stal perevodchikom Stalina (Moscow: DEM, 1993), 226.

50 Letter from Liza Chazkewitz in Rostov-on-Don, December 26, 1939, YVA: O.75/324, pp. 3–4.

51 See, for example, Michael Parrish, The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939–1953 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996), 1–51.

52 On the restrictions on communication under Stalin, see for example, Kindler, “Famines and Political Communication in Stalinism,” 255–272.

53 On the evacuation to Siberia, see, for example, Vo imia pobedy; evakuatsiia grazhdanskogo naseleniya v Zapadnuiu Sibir′ v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny v dokumentakh i materialakh, ed. L. Snegireva (Tomsk: Izdatel′stvo TGPU, 2005), vol. 1: Iskhod; Kristen E. Edwards, Fleeing to Siberia: The Wartime Relocation of Evacuees to Novosibirsk, 1941–1943, PhD diss., Stanford, CA, Stanford University, 1996.

54 On the evacuation to Kazakhstan, see, for example, Kaganovich, “Evreiskie bezhentsy.”

55 Shulamit Shalit, “Mne rekomendovali vziat′ psevdonim. (Mark Kopshytser, 1923–1982),” http://berkovich-zametki.com/2005/Starina/Nomer9/Shalit1.htm, accessed March 12, 2016. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewer of the manuscript who gave me the clue to search for Efim Ginsburg in this publication.

56 No date, YVA: O.75/324, p. 406.

57 See the section “August 1942” for details of when and how the members of the Ginsburg family were murdered.

58 Boris Urlanis, Rozhdaemost′i prodolzhitel′nost′ zhizni v SSSR (Moscow: Gosstatizdat, 1963), 103–104.

59 Although in the information submitted to Yad Vashem, Efim Ginsburg’s widow wrote that Avraham Greener had perished in 1942 during the Holocaust in the Rostov district, there is no reference to this in the correspondence.

60 Extermination (istrebitel′nyi) battalions were established in accordance with the decree of the Council of People’s Commissars from June 24, 1941 “On the protection of enterprises and institutions [against enemy spies and saboteurs] and the establishment of extermination battalions in the endangered areas.” Their members (both men and women) were selected from people considered to be ideologically reliable. They underwent a short military training, and their service was regulated by the Military Code of the Red Army. At the same time, they continued with their usual employment. Several times a week (as the front line moved nearer, this frequency increased) they gathered for training and at night they guarded sensitive establishments, carrying their weapons. When the Germans approached the city, some of the extermination battalions participated in the fighting, while others formed the nucleus of future partisan units. On the extermination battalions in the North Caucasus, see Elena Nikulina, Istrebitel′nye batal′ony Stavropol′ia i Kubani v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny: 1941–1945 gg., PhD diss., Pyatigorsk, Piatigorskii gosudarstvennyi lingvisticheskii universitet, 2005.