Читать книгу Higher Love - Kit DesLauriers - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THIS TIME FROM THE TOP

ОглавлениеMonday, May 24, our twenty-second day on the mountain, we woke to the alarm at 5:15 a.m. In a Vicodin hangover, we looked outside the tent to see incredibly calm, clear skies.

“I can’t believe it!” I said.

We scrambled to get ready and were just a little behind schedule when we climbed out of camp at 7:15 with our three trail-breaking recruits behind us. Sleeping patterns aside, it’s hard to get moving early in such cold temperatures.

We climbed fast, weaving in and out of the sun’s shadow line as we crested the short section of fixed lines at the top of the headwall. Reaching the 17-camp zone took four hours this time, after having taken five hours just days before. We sat for a moment to drink tea as our partners for the day passed us, and I cached the thermos there when we were finished.

Just before 2:00 p.m., we reached the 18,400-foot elevation of Denali Pass and caught back up to them so that we could swap leads breaking trail again. Over the next hour, Rob’s pace slowed and the weather deteriorated just enough to be annoying without being dangerous. The sky turned from blue to white. While the visibility diminished to the point where we couldn’t distinguish between the snow and the horizon, at least the wind didn’t kick up like it had been doing for weeks. Once we reached the Football Field, a plateau at 19,500 feet that’s actually much larger than a football field, I ran into an entirely different kind of trouble. While having your husband declare his love for you at the top of his lungs might not seem to be a sign of trouble, that’s how it started.

“I love you! I love this life!” Rob said. “Isn’t this amazing? I’m so happy!!!”

“Yeah, it is amazing,” I answered. But that went without saying. Though Rob is a positive person, this was a little extreme.

He stood rooted to the mountain looking like he had no plans for moving forward. “Aren’t you happy, Kit? What’s wrong with you? I love you so much and I’m so happy!”

I gave him a peck on the cheek and searched his eyes for some explanation. He looked normal. Because I was spooked by this new attitude, I faked the enthusiasm that I guessed he was looking for and hoped it would get him moving again. “I’m so happy, too! I love you, too!” My heart raced. I’d never seen this behavior in anyone before. I turned away and regarded Pig Hill above us, and then I started climbing into the white clouds that had settled in.

“How can you not be happy, Kit?!” Rob shouted behind me. “I love this! We’re about to summit Denali! It’s so beautiful and I feel so much love!”

By now the beauty was barely visible. The fog had blocked our views of the summit and the surrounding peaks. When I turned around, I saw that Rob still wasn’t moving. I suddenly recalled from my wilderness emergency medical training that euphoria can be a symptom of hypoxia, oxygen deprivation that hinders normal functions like cognition and staying warm. We should go down right now. If it gets really bad, I have the rope in my pack and I guess I could tie him in to it. But what if he resisted me? Though he hadn’t taken a fall anywhere, he was behaving as if he’d suffered a head injury, and while he wasn’t being combative, I was afraid he might.

I walked back toward him along the Football Field. “Rob, I am very happy, but we still have a long way to go,” I said gently. “It’ll probably take us another hour and a half to summit if we keep moving. I think you’re having a reaction to the altitude and maybe we should go down.”

“You don’t get it! I’m fine, I don’t need to go down. I am just so happy that I need to tell you and I want you to be happy, too. This is amazing!”

I was no longer spooked, I was scared. If I turned around and went down, would he follow me or would he stay up high and maybe even go for the summit alone? Given that possibility, I couldn’t leave him. I just hoped I wouldn’t have to get the rope out. That would be a clear signal that although our survival depended on cooperation, we’d moved deeply into one-against-the-other territory.

“What’s your problem?” he yelled. “Aren’t you happy, too?”

I had to make a decision. By now we’d wasted half an hour on this game and it was already 4:00. If Rob didn’t start moving soon, I’d have to figure out how to get him to go down without even trying for the summit first.

Determined to go up if at all possible, I opted for the tactic of climbing toward the summit and seeing if he would follow me this time. And to my tentative relief, once I put enough distance between us, he did. Constantly but discreetly looking over my shoulder, I slowly kicked steps up the snow on the steep section of the summit block, and at the summit ridge I stopped and waited.

At the top of Pig Hill, two of the climbers who’d started the day with us were on their way down from the summit. “My husband is acting really weird and I’m scared,” I told them. “Will you tell him he needs to keep moving?”

They looked at each other and then at Rob, who was several paces behind me. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” one of them said. “He looks fine to me.”

There wasn’t time to go into detail before Rob would be in hearing range, so the other climbers went on their way and all I could do was stay calm on the surface and hope we’d make it without further incident.

When Rob reached the top of Pig Hill, he started on a whole new soliloquy about our beautiful life, and no amount of hyperbole on my part seemed to satisfy him. So, nervously, I just continued climbing.

At times there were undulations where I couldn’t see Rob and I worried for his safety, but stopping anywhere short of the summit would have only meant I’d have to waste precious time while he took a break to rant again. This had become an agonizing pace and we simply didn’t have time for this game anymore. So I walked slowly up the ridge, continually glancing back at Rob. Sometimes I paused to wait for him to get closer, but I never wanted to let him get within earshot. Just close enough that he knew I wasn’t abandoning him, just far enough to silence his outbursts.

When I reached the top, the poor visibility created the sensation of being inside a jug of skim milk. I could see only as far as the start of the Football Field below. Although I was elated on one level, I was also intensely concerned about us and the recent twist of events. It was 7:15 and we’d been climbing for exactly twelve hours. We had a 6,000-vertical-foot ski descent ahead of us, and my husband was acting like someone on Ecstasy.

I took my skis off my pack, switched from glacier glasses to goggles, added a down jacket to my layering system, and generally prepared myself to ski. My plan was to ski off the summit almost as soon as Rob arrived in order to head off another bizarre encounter, but when he arrived at the summit ten minutes later and saw me ready to push off, he was clearly agitated.

“You weren’t going to wait for me? I can’t believe you! I’m so happy and you’re so mad.”

“No, Rob, I’m not mad. This is wonderful. It’s just really late. It’s after seven and we’re on top of Denali. We’re only halfway—we have to get down.”

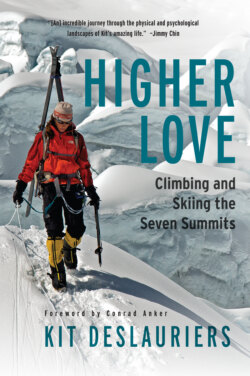

Kit on Denali’s West Buttress, 2004 (Photo by Rob DesLauriers)

As he began to make the transition to his skis, the third climber from our original group arrived. He was the last person who would summit that day, and this was my last chance to have someone else try to talk sense into Rob and maybe break the spell he was under.

“Thor, help me,” I pleaded out of Rob’s earshot as Rob bent over to step into his ski bindings. “Rob is acting crazy and I think it’s the altitude. Can you talk to him and tell him how serious this is and how much we need to keep moving?”

When he looked at me as if I were the one whose mental state was in question, I realized how little these other climbers knew us.

“I’m not saying anything,” he said. “I have no idea what’s going on or who’s actually having trouble.”

“OK,” I said, just barely able to wrap my mind around his viewpoint. I was starting to feel like I was mentally hanging by a thread, too.

Soon after Thor started back down the ridge on foot, we began our ski descent, which proved only slightly dangerous off the summit block. Wind-slab conditions caused small releases of snow as I made ski cuts down and left, down and left to position myself above the runout of the Football Field. Normally I have to watch Rob’s technique carefully to see if he’s having to adjust to difficult conditions, but off the summit of Denali he was clearly skiing in survival mode, although being a world-class skier, his survival mode was equivalent to most people’s standard ability.

After descending Denali Pass and returning to 17,200 feet at the entrance to the Rescue Gully, Rob seemed almost entirely normal again, but just in case, I decided not to bring it up yet. The entrance to the couloir of the Rescue Gully held hard blue ice at the top and was every bit of fifty degrees in steepness. We talked about pulling out the rope for a belay, but it was almost 9:00 at night and decided against it. Besides, it was only me who thought I might want it.

The recent snowstorm had done little to make the conditions at the top of the gully less slick, but this time I didn’t have the luxury of backing down and saying, “I don’t care about skiing the mountain.” I did care and I had to stay strong for both of us. It wasn’t over yet and I still felt like I had to lead the way.

When I looked into the couloir, there was a small amount of new snow on top of the same blue ice with the same jagged rocks poking through it as when I’d inspected it a week before. I hadn’t even wanted to down-climb it then, and now I was going to ski it. What I do is a lot about risk management, and this was one of those moments.

If I only do it once, then the chances of an error are less than if this were my second time. Maybe I’ll use my ice axe for this upper part.

While that thought may have justified the caution I’d shown last week, today I had to face the conditions that were still less than ideal if I was going to make a complete ski descent.

Can you really do this, Kit? What if your ski edge slips on the ice? What if it gets caught up on a shard of rock and you lose your balance? It’s a long way down, 1,500 vertical feet before it opens wider to the glacier below, and the crevasses down there would swallow anything.

A few deep belly breaths helped expel some of the doubt, and as if I were observing myself from a distance, I saw clear images of the intimidating lines I’d skied during the World Freeskiing Tour just months before. This objective bird’seye view helped me assess the risk and realize that if I could do that, I could do this. So I harnessed the empowered feeling I’d experienced after skiing those lines with conviction and sidestepped through the rocks that guarded the entrance to the Rescue Gully.

Once in it, I made myself focus on the move ahead instead of the expanse below. The waning light and the clouds that encompassed us helped me to keep my view on the turn ahead, and I adopted my approach to technical moves. Just do what’s right in front of you, Kit. When an ice bulge in the middle of the couloir felt like it wanted to push me into the overhead rock wall on the left side, I made a careful kick turn, switched the ice axe to my right hand and the ski pole to my left, and sidestepped down twenty vertical feet until I reached a patch of snow that had been deposited on top of the blue ice. After holstering my ice axe and pulling my second ski pole from its special spot on my back, I made a few turns on the “relaxed” fifty-degree angle and backed my ski tails up to the rock wall on the left to wait for Rob.

Rob made it look a little easier than I had, but he took the same level of care, and with bursts of four or five ski turns at a time before resting our burning lungs, we leapfrogged down the rest of the couloir. During each rest, we scanned the crevasse field below for a way to ski through it that would reconnect us to the normal climbing route near the gaping bergschrund, where the glacial ice was separating from the steep mountain. Occasionally, some ski tracks were visible from a group that had passed through earlier in the day, but in the waning light nothing was obvious, so we worked together by shouting things like “Go right!,” and “Hole here!” Rob’s speech had become as fluid as his skiing by now, and I was no longer worried about the trouble we’d experienced up high.

We carefully navigated the crevasses until we skied over the biggest one, the bergschrund, and from there it was like a low-angle powder field until we got back to 14-camp. It was 10:00 and we immediately collapsed in our tent for a deep sleep.

On the morning of May 25, our twenty-third day on the mountain, we rehydrated and packed our gear. The pilot won’t come to pick up a climber at the 7,200-foot base camp until the ranger on patrol there makes the call verifying that the climbing party is indeed ready. Exit from the mountain is on a firstcome, first-served basis, and we wanted to get our names in the queue as soon as possible. A lighter load meant an easier descent, so we pulled the same trick as the Don’t Worry Be Happy team had and gave our extra food and fuel to anyone at ABC who would take it.

Having had experience with skiing rescue sleds during my stint on ski patrol in Telluride, I figured we’d be faster if we put only a little gear in our packs and the bulk of it on one sled, tied the second sled on top of it, and then worked together to ski our load down. Rob agreed, so we attached a rope from the back of his climbing harness to the sled, and as he skied away and pulled the sled behind him, I skied holding the tail rope and pulled tension on it whenever a brake was needed. This technique required great communication skills, because with all the crevasses and side hills to negotiate, we needed more space to get down the mountain than the narrow footpath made by other climbers. Fortunately, by this point Rob and I were a dialed team. We’d been to the top of the mountain in a single push from 14-camp to the summit, navigated the altitude euphoria that had threatened our survival, and successfully skied down. Now, with Rob’s mental function fully restored, we simply had to cooperate in order to get to the bottom of the mountain, and that’s what we did, making it from 14-camp to base camp, 7,000 feet below and ten miles away, in less than five hours.

Receiving the extra food and fuel from the Don’t Worry Be Happy team had worked out brilliantly for us, allowing us to comfortably stay on the mountain for longer than we’d planned, but giving it all away again on the morning of our final descent didn’t turn out to be such a smart move. It was snowing too heavily for planes to fly into base camp on Kahiltna Glacier, and we’d be staying there for longer than expected. The “ounces, ounces, pounds” mantra had backfired—Rob and I had almost no rations left.

On the evening of our second day at base camp, I finally poked my head out of our tent, and good fortune was waiting just outside.

“What’s up, Kit?” said one of the guys we’d met at 14-camp. “I haven’t seen you in two days!”

“My mom always told me, ‘If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all,’ so I’m trying not to, but I’m really hungry.”

He laughed and ducked into his tent, and when he returned he was carrying two packages of dried soup mix and two small pieces of chocolate.

“Oh, thank you! Are you sure?”

“No problem,” he said with a smile. “Your mom was right, but we’ve missed seeing you around camp.”

Rob and I had been fortunate to climb and ski the mountain in our own personal style, so sitting still at the end of it with almost no food for a day or two was a small price to pay. It was just part of working with the mountain. There were no more endless questions in my head about what to pack on the next climbing rotation, when to leave camp, or whether I should make more water. I was content to read a book or simply stare at the yellow nylon fabric of the tent ceiling and think of almost nothing.

On the third morning at base camp, the mental break ended when it was our turn for a flight back to Talkeetna, but when the pilot arrived he asked us to make one last decision. The new snow on the low-elevation glacier was so wet and heavy that for the Cessna 185 to get off the ground, something—or someone—had to be left behind. The plane could take only one of us and our gear or both of us and no gear.

Which do you think we chose?