Читать книгу Higher Love - Kit DesLauriers - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE DREAM COMES TRUE

ОглавлениеWhen Alta and I drove into Ophir, Colorado, for the first time on a late-April day twelve years before the Denali expedition, I craned my neck from side to side to see the tops of the mountains on both sides of the two-mile dirt road that served as the only western entrance to the narrow valley. They rose 4,000 feet straight up, and even when I leaned over the dashboard of my pickup to see, they could easily hide their summits from me.

Although I’d never been here, this valley with such high walls felt strangely like home, and before we’d even pulled into town, I had an epiphany. “We’re either going to live here for a long time or move someplace far away,” I said to Alta, who was on the front bench seat next to me. “Like Jackson Hole, Wyoming.” It wasn’t a plan, just a vision from out of the blue. I’d never been to Jackson Hole either.

We parked outside one of the eight houses on the former silver-mining town’s main street. It was a tiny, nicely renovated old miner’s cabin where I’d accepted a caretaker’s position for three weeks. All I was getting in return for the unpaid position was three weeks of living under a real roof and exploring this beguiling valley at 9,700 feet above sea level on the edge of a national forest in the San Juan range, and I couldn’t have been happier.

Alta and I didn’t waste much time settling in. I finished unloading the truck before dinner, and by the next morning I had a plan: Every day we’d walk up the Ophir Road and take a right onto the mining road or foot trail that lay just beyond the one we’d taken the day before. Up, up, up we’d go until either I ran out of time and had to go back and get ready for work as a waitress in Telluride or the trail disappeared due to neglect or dead-ended at an old mining site.

I’m continuously creating a map in my mind, and I feel compelled to fill in the blank spots on it. Maybe I have the explorer gene I read about in National Geographic. Or maybe I’m just irresistibly drawn to the unknown in general, despite the dangers it so often harbors. Whatever the case, by the end of those three weeks of daily adventure travel, we hadn’t missed a single trail in the arc of the valley above town, south to east to north, and I’d gotten the sense of place I was looking for. Another blank spot filled in.

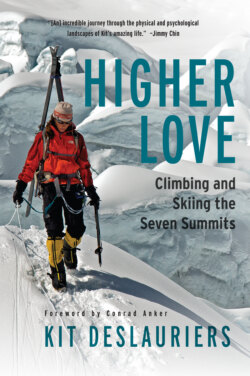

Kit and Alta above Ophir Pass, Colorado (Photo by Ace Kvale)

Alta and I also established a new partnership in that time. Because of his wolf instincts, he often ran ahead of me, but he knew we needed to stick together since we were all that each other had in the world. He didn’t want to lose me any more than I wanted to lose him. When he’d been off exploring for a little longer than I was comfortable with, I’d howl and within a minute he’d appear from the forest or from around a bend in the trail ahead with his head cocked and a panting, What’s up? smile on his face. Each time this happened, I felt like the most fortunate girl in the world to be able to run around the mountains with a wolf who would come when I called him.

Eventually, Alta began coming back to check in with me without being called. When it was on his own terms like this, instead of giving me a questioning look from the path ahead, he’d prance right up to my side and touch his nose to my hand or leg. I always acknowledged his check-ins with a “Good boy” or some wolf-speak—“ararr, ararr, rarr”—and gave him a rub on his head and a pat on the hindquarters to let him know he could go again.

By our last day of caretaking at the cabin, I knew we’d found a home in this valley and I headed for a house on the high side of town that I’d learned was a rental property. As a rule, turnover among renters was almost nonexistent in Ophir because the population was so small—120, to be exact—but I had everything to gain by knocking on the door at 8:00 a.m., Alta at my side. A man in his early twenties opened the door with a surprised look.

“Good morning. What’s the chance that you have a room for rent?”

His jaw dropped. “How did you know? Just last night I decided to join the Peace Corps and I’m leaving tomorrow. You can have my room. Your timing is amazing—I’ve been sitting on the acceptance letter for three weeks now. Come on in, let me show you around.”

Looking right at home while he waited for me on the front porch with a view of town and three 14,000-foot peaks to the west of the valley, Alta seemed as content about the prospect of living here as I was.

In the years that followed, we lived the balance between freedom and safety that we’d struck on the trails around Ophir in our first weeks in town. From the moment he’d first climbed to the top of my head as a two-week-old pup, Alta had always sought out high places—it couldn’t have been any clearer that it’s what he’d been born to do. For him, freedom meant the freedom to go to the highest point he could. And as we climbed the nearby peaks, it was common for him to leave me wondering where he was for as long as a half hour as I scrambled behind him up mountains without trails. It wasn’t until I’d reached the saddle between two mountains, or a false summit, or even the summit itself that I’d finally see him again, contentedly sitting on his haunches and gazing into the distance, waiting for me.

The times when he disobeyed my calls—the times when he wasn’t willing to compromise in terms of the freedom that was his birthright—were rare. As deeply connected to me as he was, that couldn’t always compete with the lure of being where he belonged. He knew his place in life, and sometimes all he could do was follow his heart to that place.

Many years later, while I was trying to decide whether to commit to competing on the World Freeskiing Tour for a second time, I came to understand how Alta must have felt. Ultimately, it wasn’t about making a choice—it was a matter of simply doing what I’d been born to do. Just as it had been on Denali.

“Are you going to compete on the Freeskiing Tour again this year?” the man asked me as the quad chairlift carried just the two of us up the mountain on a perfect January morning of powder skiing in Jackson Hole.

I’d just met this friend of a friend less than an hour ago—an hour spent mostly immersed in deep snow with our group of six—and here he was jumping right into my mind.

With only a brief pause to wonder who this omniscient figure was, I let myself dive heart-first into the question I’d been musing about incessantly. Even as I’d been dropping into pillows of waist-deep snow that morning, the question had been eating at me. The first competition of the season was a week away, and because the World Freeskiing Tour is a points series, it’s important to earn some at each stop on the tour. If I were to compete again, I wanted to win again, but if I missed the first event, I might as well not show up for the others.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I mean, what’s it all worth? I won last year and proved to myself that I could do it. After all that time and energy, I still barely broke even with all my expenses.” The prize money for the women was about half of what it was for the men, and unless you won first place, you took a loss on the deal. The real money was in the sponsorships, and I didn’t have any that paid. “What for, then?”

I didn’t tell my new friend about the other conversations I’d been having with myself, such as:

Wouldn’t it be nice to go out on top?

What if you lose?

Kit, it’s pretty pathetic to think you don’t want to compete again because you might not win again. Just because you even thought that, you know you should do it.

Maybe you’re too old to keep playing around at the skiing thing, Kit. You just turned thirty-five, and even though you’re winning and skiing at the top of your game, the sponsors and the filmmakers don’t seem to notice you. It’s just not sexy to be older than the rest of them and married.

You have to figure this out soon. Sure, you’re automatically eligible to compete because you hold the title, but there aren’t many days left to decide.

As we passed two more towers on the Thunder Lift, I continued listening to the voices in my head, and my lift-mate appeared to digest my answer.

“You have to compete again!” he finally said. “I’ve never seen another woman ski like you. I’d like to sponsor you.”

My brain began to spin like a hard drive and took me back to the years when living my lifestyle of choice had made for hard times. I revisited my days as a waitress and a stonemason in Telluride. I had a fifteen-mile daily commute on mountain roads, and when my truck began misfiring, I realized it needed a tune-up I couldn’t afford. I asked the local mechanic to sell me whatever kind of spark plugs the six-cylinder engine used so I could do the work myself, and I borrowed the necessary wrenches and a spark-plug gauge from a neighbor. All set to make the repairs, I became nervous about my ability to do a job I’d never done or even seen done before, and I decided to skip the tune-up and go skiing instead.

Two months later, on a day off in February, I headed outside to load my skis into my truck and found that the snow was up to my waist and blowing sideways. With my ski goggles on, I shoveled a trench to my truck and dug it free. Shivering with my cooling sweat, I slid into the driver’s seat and turned the key. Nothing. Not even a misfire. I’d known this moment was coming, though, and as the first ski tracks of the day faded from my imagination, I resigned myself to the task. I opened the hood and attached a tarp to it, creating a lean-to shelter from the storm, and climbed into the engine compartment and taught myself how to change spark plugs so I could go powder skiing.

Then the hard drive spun me back to a campfire moment in the desert after a day of climbing sandstone towers. An impressive twentysomething climber named Sue Nott was visiting our weekend gathering in Indian Creek, and I wondered out loud how she could be so good at the sport. How could she always be on the road climbing instead of working to support herself? And why did she have such a nice truck? Someone whispered her story to me: A friend of her family had seen her talent as a climber and wanted to help her live her dream of being a professional climber, so he sponsored her (and paid for the truck).

From that moment on, I’d dreamed of having someone believe in me enough to sponsor me. More accurately, I dreamed of being worthy of sponsorship.

When the disk drive stopped spinning, I was back on the Thunder Lift, and a wave of joy was rushing through me. If this stranger was going to give me money to ski, then what I wanted to do with my life was actually OK. Not just OK—it had purpose. It was worthy of making it my profession.

Instead of sharing these musings, all I could muster was, “Can we put the bar down?” I thought I might pass out and fall off the lift.

“I want you to not worry about money,” he said. “Don’t sleep in your van in winter just to compete. I want you to buy the plane ticket, rent a car, book a hotel, and don’t share a room. Just go out and win.”

“You’re serious?”

He nodded.

“That’s amazing. Thank you.” It sounded so insufficient, but I had no idea how to properly acknowledge such a gesture. I was still trying to comprehend it. “Um . . . what should I do in return?”

“Do the right thing. If someone asks you to meet with a girls’ afterschool program, for example, I hope you’ll say yes.”

That’s it? “Of course I would. I’d love to.”

It was the stuff of a twenty-two-year-old’s dreams, and for the next few hours the thirty-five-year-old’s self-protection mechanism didn’t allow me to fully believe it would actually happen until he stopped by our house after the chairlifts closed. With my stomach a jumble of excitement and Rob watching in astonishment, the man who was about to become my secret benefactor put a check made out to me for a lot of money on our kitchen counter. “Spend it on skiing,” he said. Then, reminiscent of St. Nick laying his finger aside his nose, giving a nod, and rising up the chimney, my benefactor walked out the front door, straddled his motorcycle, and drove off, leaving a trail of fairy dust that only I could see.

I WON THAT FIRST EVENT of the Freeskiing Tour at Whistler/Blackcomb a week later, and I was on my way to another win at the second event in February when my health suddenly became an issue. It was a three-day competition at Snowbird, Utah, that also served as the US Freeskiing Nationals, and I was sitting in first place when I woke up on the final day with congested sinuses, a sore, swollen throat, and a severe case of sleep deprivation. I’m not prone to getting sick, but this virus wasn’t to be denied. I just had to give in and acknowledge that it had taken hold after lurking for the past two days. But what I only slowly realized was that I didn’t have to give up. As I lay there, I thought about everything I’d invested into being in that place on that day, how fortunate I was to be the reigning champion, how I was in first place because of the score I’d earned on the first run the day before, how I was competing for the second year because I wanted to and because I’d thought it would be pathetic not to compete just because I was afraid of not “going out on top.” And I thought about the positive teachings of my favorite sports psychology book, Chungliang Al Huang’s Thinking Body, Dancing Mind, and pictured myself at the starting gate on Mount Baldy and skiing an aggressive, flawless run. Ultimately, I realized I didn’t need to be a victim of my virus. I could still give every bit of myself to my ski run that day, mentally and physically. There was everything to gain.

Rob had arrived the evening before so he could be there for the finals, and as I walked over to the coffeemaker in our hotel room, I said to him over my shoulder in a raspy, barely audible voice, “Do you know what?” He laughed at the sounds I could hardly make and mimicked me in response. “No, whaaat?”

I turned and looked at him. “I can win this thing.”

He smiled. “Yes. You can.”

Adrenaline helped me to temporarily forget about my condition during my finals run. Luckily, flying down a 2,000-vertical-foot slope without hesitation takes less than two minutes, and I skied it perfectly. The points showed that I’d won the event, but then in a move not uncommon when the skiing conditions are beautiful and the competition stiff, the judges decided to amp up the crowd with a “super final.” The top five men and women would head back up the mountain to ski another run, and the score from the super final would be factored into the overall standings.

A wave of exhaustion washed over me, I felt cheated out of my win. I’d given everything I could for three days despite my illness, and I was fatigued to the point of depression. In the grip of the natural cortisol downer that had followed my final-run adrenaline rush, I just wanted to go back to the hotel, lie on the bed, and watch TV.

I tried to rally the other skiers to resist the super final. Though the others had a chance to improve their positions, they could also make a mistake and crash and end up lower in the standings. But while it was clear that no one really wanted to muster the intensity it takes to ski all-out again, one by one I watched them head for the tram to get ready to make that super-final run. There was nothing for me to do but grab a free Red Bull from the competitors’ tent and follow.

In finals and super finals, runs are in the opposite order of the standings, which meant I would again go last. As the others chatted until it was their turn, I hung back from the start, which had been moved even higher up the mountain to make the super final a bit of a different course. When no one was left on top of the mountain but me and the person in charge of counting down the start, I sideslipped into position, buckled my boots a little tighter than normal, and stared into the fifty-foot rock face to the skier’s left of the starting gate.

It wasn’t a premeditated focal point, but in it I found stillness and I discovered myself appreciating the beauty of the boulder’s composition. Before long, though, the sore-throat tightness that had become worse throughout the day vaulted into my awareness. I knew I’d be in trouble if I skied with that thought in the front of my mind, so I repeated to myself what I had said that morning: “I can win this thing.” Immediately, I could see past the sickness—I could see myself skiing a winning run—and I knew that if I held on to that vision, the virus wouldn’t rule my physical performance.

Just then the announcement came over the radio that the judges were ready, and the starter asked me how I was doing and if I was ready. As feverish chills made me shudder, I moved into position in the starting gate and smiled.

“I am ready,” I said in the small croak of a voice that I had left, “and I can win this thing.”

And I did. After executing some huge high-speed turns and a pair of twenty-foot jumps, I entered the most perilous part of the course with only 800 vertical feet to go. It was covered with hundreds of punjees—the tops of ten-foot trees that are almost buried in the snowpack—waiting to ambush skiers crazy enough to venture into this maze on a forty-five-degree slope. The day before, I’d gotten tripped here on a practice run and tumbled to the edge of a sixty-foot cliff, stopping only because I had the composure to grab for the bare treetops every time I flipped uncontrollably, each tree slowing me just enough to stop at the edge. So I thought twice—at least—before attempting it again. This was where I could win it, though, by acing the all-important degree-of-difficulty category, and that was the deciding factor. With the punjees coming at me fast, I made precise turns and pole plants, almost like bunny hops, picking myself up and landing again without touching any of the sharp treetops. Now all that was left was to set up for the finale.

At the top of a towering cliff that was way beyond anything any of us women were willing to chuck ourselves off, I made a swooping turn to the right and three more tight turns down through the rocks to my takeoff. With hands perfectly poised in front, I skied my biggest air of the day—thirty feet—picked an untouched pillow of snow, and landed softly to the deafening roar of the crowd.

It was exactly as I’d visualized: nearly perfect.

BECAUSE OF MY ILLNESS AND because I always felt a little out of place at the freeskiing after-parties since I was ten years older than most of my competitors and married, Rob and I decided to go out to dinner alone that night at the restaurant on the top floor of the Cliff Lodge. When we walked into the Aerie Lounge, we were seated by the window adjacent to Snowbird owner Dick Bass and his son, Dan. Rob had met Dan at the awards ceremony, and they picked up their conversation where they’d left off and soon incorporated Dick into the mix.

Dick had given a speech at the ceremony, and he proved just as eloquent in casual dinner conversation. He wondered aloud about me, and whenever I could croak out an answer, he drew a parallel between the philosophical approach I take to my sport and the approaches he saw among climbers during his bid to become the first person in the world to climb the “Seven Summits,” the highest mountains on each continent.

When we finished dinner, Dick insisted we join him in his private office, also on the top floor of the Cliff Lodge, so he could show us his plans for Snowbird. As much as I wanted to go back to our room and sleep heavily, we joined him around an oblong, highly polished conference table upon which sat a model of Snowbird as he envisioned it in the future. With more tram access to mountains higher and farther away and a summer business centered on body, mind, and spiritual wellness, it was a dream worthy of a man as magnanimous as Dick Bass seemed to be.

I didn’t see Dick again before we left, but as we checked out of the hotel early the next day, the clerk handed me a signed copy of Seven Summits, the book that Dick had written with Rick Ridgeway. As the competitions of the 2005 season went on into spring, Seven Summits was always on my hotel bedside table right next to Thinking Body, Dancing Mind. While reading it, I took note of how Dick called himself a high-altitude trekker as opposed to a hardcore alpinist type of climber, and I began to wonder if maybe I could climb and ski those same peaks that he’d “trekked.”

By the time I finished the book, the idea was speaking to something primal in me. Dick had climbed Denali before he dreamed up the idea of the Seven Summits, and I’d climbed and skied Denali the year before with Rob. I’d written on my life-plan game card that I wanted to climb an 8,000-meter peak; now I was feeling an undeniable pull toward the rest of these high places.