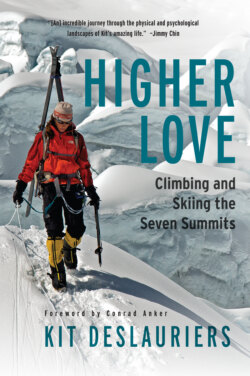

Читать книгу Higher Love - Kit DesLauriers - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

“YOUR PASSPORT SURE

WILL BE FULL”

ОглавлениеWith money to spend on skiing, life was different. For one thing, instead of driving our van home twelve hours from Kirkwood, California, like we’d done the year before, this year Rob and I could fly back after the final event of the World Freeskiing Tour and catch closing day at our home mountain in Jackson Hole. After I stood on my last two podiums of the season, one for second place at the Kirkwood comp and the other for winning the overall 2005 Women’s Freeskiing World Championship title, I hopped into the rental car and off we sped to the Reno airport.

Indirectly, the money also improved my skiing. I skied better during my second tour than I ever had in my life, and I have no doubt that it’s because someone believed in me enough to make that investment. Having a sponsor was like having a constant source of affirmation. I even found myself calling him after a win before I called my parents.

On closing day, he hosted an après-ski party, and as Rob and I pulled up to the restaurant, I was tingling with excitement about sharing my success stories of the season with him. But I also felt nervous, like a traitor, because my immediate plans didn’t include much skiing. I was sure someone at the party, probably him, would ask me, “What’s next?” I cringed at the prospect of having to say, “I’m enrolled in a graduate program for a master’s in landscape design that starts in August at a school in Massachusetts.”

Actually, I’d been enrolled for two years but had deferred my acceptance so I could compete on the Freeskiing Tour. Having been raised to tell the truth, I’d been honest with the admissions officer the year before when I requested my second deferral: I told her I hadn’t imagined I could win the first time, and now I wanted the chance to do it again.

After that, I’d be ready. I’d have gotten it out of my system. They believed me because I believed it myself. After all, going to graduate school for landscape architecture had been on my five-year list for six years.

A small prestigious school, the Conway School of Landscape Design seemed to hold the key to my next career and lifestyle move. I wanted to build on the skills I’d developed during my twelve years as a stonemason, when I created outdoor spaces that were in harmony with nature. I loved the art form of building with rocks, and if I became a designer, I could have a profession that fit my values without having to lift all those rocks myself for the rest of my life.

“Why do I feel so nervous?” I said to Rob as we sat in our car in front of the restaurant. “How am I going to let him down?”

Ever since I’d met my husband six years earlier and he seemed to look right into my soul, I’d known I couldn’t conceal anything from him. I had the same feeling just then when he said, “How are you going to let yourself down?”

He was right, of course. I realized that I still wanted to ski full time even though I’d achieved my goal and won the Freeskiing Tour twice. I wasn’t done, but what was I going to do?

Rob released me from his knowing gaze, got out of the car, and led us inside, where I decided not to mention going back to school. Instead, we simply celebrated the successful end of another ski season and another Freeskiing Tour.

THE MORNING AFTER THE PARTY, I picked up the phone and made an appointment with Carol Mann, a soul reader I’d wanted to meet for years. If ever there was a time in my life when I needed a third informed opinion, this was it.

Never having done anything like this before, I had a hard time deciding what to wear to our meeting a few days later, a concern that turned out to be absurd. After welcoming me into her enclosed porch office in a historical home in downtown Jackson, Carol began our conversation by saying, “Here are my Kit notes.” Apparently, once I’d given her verbal permission to tune in to me, she went on to fill page after page of a yellow legal pad with my soul information—how often I’ve incarnated (and in what genders), why and when I choose to incarnate, what matters most to me. Once again, someone was looking right into me. It couldn’t have mattered less what I’d worn.

Her blue eyes sparkling, she jumped right in. “I want to invite you into planetary work, because that’s who you are. That’s why the small things lose interest for you even though they’re great in most other people’s view.”

Wow. She certainly nailed that. Things like having a normal job, planning for retirement, and starting a family had never been high on my list. I felt the urge to confide. “Everyone keeps asking me when I’m going to have kids, and I don’t know. I don’t even want to think about it right now, but society tells me I should. I’m thirty-five and have been happily married for five years. Is there something wrong with me?”

“Your way of knowing is direct navigating. You will suddenly feel and know that raising a child is an enormous contribution.”

Whenever I’d contemplated becoming a parent, I thought that would amount to turning my back on a big piece of myself that I hadn’t spent enough time cultivating. Hearing Carol say this gave me some confidence that I was making the right choice. And that confidence seemed to free me to do some direct navigating right then and there. I suddenly felt and knew I would have two children before I turned forty. So there was still time. No need to embrace the pressure that others had been putting on me.

Carol interrupted my musing. “What would you like your legacy to be?”

What? Really? I was already thirty-five, but isn’t a legacy something to be pondered at least a little later in life?

Actually, Carol was on to something. This was the big question. The issue of having children had been the hors d’oeuvre, and now we were on to the main course: If kids weren’t next for me, what was?

“You have an opportunity to expand the scope of your influence. Your soul’s essence is balance—balance in body, mind, and spirit. Your soul is part of creating the nature aspect of this planet. This may sound outrageous”—she smiled—“but the job you serve on a big-picture level is planetary park ranger. Not a park ranger for a little park. Your relationship is with the planet.”

She’d done it again. Right into me.

“Planetary ecology is the planetary level of balance. Human ecology is the individual personal level of balance. You are involved with both.”

The resonance of those words brought me to tears. Actually, I already knew what I wanted to do next, but it was so outrageously big that I hadn’t known whether I should allow myself to think about it. Ever since reading Seven Summits, though, I’d felt the dream growing, whether I allowed it to or not. Over the months, the term high-altitude trekker kept popping into my head. In the book, Dick Bass had made a clear distinction between what he does and what hardcore mountain climbers do, and my mind kept returning to the fact that snow-covered mountains that don’t require elite technical climbing skills should also be skiable. If they aren’t too steep for trekkers and the snow lines aren’t bisected by the rock and ice that beckon hardcore alpinists, why not? If a trekker could trek the highest peak on each of the seven continents, why couldn’t a skier ski them?

Going back to school to get a master’s in landscape design would be a perfectly acceptable way to experience and share my connection with the natural world, but I suddenly knew that acceptable wasn’t enough for me. The direct navigating that Carol had referred to was already guiding me.

“If you don’t access the bigger picture, you are limiting what can come in,” Carol said. “Planetary is your scope. Think bigger.”

I did have a planetary dream that was so big I hadn’t dared share it with anyone. It was time to find out what it was like to go after it.

THE DAY AFTER MY SESSION with Carol, the sky in Jackson was a grimy gray, and the mood of the town was a perfect match. Most years this is what April 15 is like, with the ski lifts closed for the season and everyone on a cortisol downer that follows the adrenaline rush of a hundred days spent experiencing the bliss of flying down the mountain on skis. There’s still a lot of snow in mid-April, but usually the conditions are changing from winter to spring and skiers switch focus to mountain biking or rock climbing someplace drier and warmer than forty-two degrees. We call it the off-season, and I tended to go through serious withdrawal at the start of each one. But this April 15, I was consumed by the information Carol had given me and allowed myself the space to think bigger like she’d suggested. Outside my window, the ghost town that Jackson Hole had become overnight was so quiet that I could hear myself breathing as I sat at my computer and opened my mind to the possibilities. How big is big anyway? Is it as big as I thought it was? As big as . . .

At over 29,000 feet ASL, Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world. I’d thought fleetingly about skiing it several years before, but without giving myself permission to access the bigger picture, it had seemed too far-fetched. But now, on April 15, 2005, a day after a soul reader had given me permission, skiing Everest seemed not only reasonable but necessary. This is what I was supposed to do next. It was as clear as the fact that getting my master’s in landscape design wasn’t what was next.

As if my fingers were way ahead of my brain, I found that I was Googling information on Everest and the other five of the Seven Summits I hadn’t skied yet. On some level, I must have known that if I were really going to tap into the biggest-picture truth of what I sensed was my destiny, I had to think in a way no one else ever had. My mind scrambled for information: When is the best time to ski them? Is it even possible? Is there snow on all of them at some time of year? And, almost as important as any of these logistics, could it be done in a short amount of time? Direct navigation had told me I would have two children before I was forty—I had less than five years to climb and ski six more mountains and give birth twice.

Clearly, efficiency was going to be crucial, and I spent the next several hours planning an Everest expedition, since it would be the most complicated one. Not knowing if anyone had ever skied from its summit, I Googled “skiing Mount Everest” and found links to stories about Yuichiro Miura’s daring 1970 speed-skiing descent from the South Col (a saddle 3,000 feet beneath the summit) and Megan Carney’s 2003 ski attempt. Carney was a highly accomplished ski mountaineer and psychologist from America who’d spent years honing her skiing skills in the French Alps and winning several extreme ski competitions before trying Everest. While she wasn’t successful in her attempt to summit, I’d heard stories of how tough she was, and based on dispatches from her autumn 2003 trip posted on the Berg Adventures website, I surmised that once the climbers had been acclimatized and were in position to summit, they just didn’t have the right conditions.

When my brain was saturated with information, I walked away from the computer and thought back to my session with Carol. She’d cautioned me to avoid getting caught up in human drama, trauma, and especially melodrama, because whenever I’m around people who don’t believe in me, I tend to lose faith in myself. She said that I was highly attuned emotionally and that the downside of that is being susceptible to swings that could knock me off balance. For me to have the greatest clarity, I needed to maintain my emotional balance. “It isn’t about you not feeling emotions,” she said. “It’s about you allowing them to flow through you.”

In light of this, I decided to be hyper-careful about sharing my dream with others. This was a private journey, not a public challenge. And I wanted to keep it that way, at least until the journey was completed. The question was, where to begin? Besides Rob, who could I share this dream with who would be only positive and supportive, with no room in their lives for holding on to fear, anger, or hatred? I’d read online that Carney had felt completely supported by Wally Berg, who’d organized her Everest expedition through his company, Berg Adventures. As a woman doing things that most people don’t think are possible, I carefully vet whether someone’s energy is supportive of me or whether he thinks I’m harebrained. Berg had believed in Carney, and that was a good sign. I picked up the phone and called his home office in Canmore.

“Are you planning a trip to Everest soon?” I asked.

“Yes, for autumn 2006,” he said. “We have some people interested.”

“Great. My name is Kit DesLauriers and I’d like to be on that trip. I’m planning to ski from the top.”

There was a brief pause and I wondered if Wally was Googling me. “I led an expedition in 2003 where Megan Carney attempted the same feat,” he said. “I think it’s totally doable.”

We discussed a few more details, all of them positive, and then I hung up feeling almost numb. It didn’t feel real. I’d put the process in motion. I’d allowed myself to think big, and I’d come up with an even more ambitious list of goals than the one I’d been pursuing since Rob and I first played “the game.” Yes, I’d wanted to climb an 8,000-meter peak, but now suddenly I was on a course for the top of the world, to try to ski it. And I couldn’t believe it felt so right—exciting and comfortable at the same time, as if I’d been walking this path ever since reading Dick’s book.

Meanwhile, back on Earth, there was work to be done. Thanks to Wally’s support, Mount Everest was on my calendar for autumn 2006, and somehow I had to fit the other summits around that. So I dug into the handwritten notes, bookmarked pages, and printed articles strewn across my desk and the floor.

First I learned that Vinson Massif, Antarctica’s highest peak, can be skied only in late November or early December (Antarctica’s summer) because it’s the only time that the logistics company flies to that part of the continent. I put it on my calendar for 2005.

Aconcagua, in Argentina, also looked best in late November into December. Given its proximity to Antarctica, I wondered if I could do it right after Vinson Massif. I scribbled a reminder to keep an eye on the snowfall during the Southern Hemisphere’s approaching winter season.

Russia’s Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe, was on the North American seasonal calendar and would be best skied in early June just like our big peaks here in the Tetons. Perfect—how about kicking things off with Mount Elbrus six weeks from now? Without another thought, I emailed John Falkiner, who had skied Elbrus by the standard southern route and had long wanted to explore the seemingly unskied remote north side. And after the expedition that Rob, John, and I had shared on Siberia’s Mount Belukha in 1999, I figured he’d agree that the north side of Elbrus was another adventure we needed to have.

Kilimanjaro, in Tanzania, presented a special problem: It seemed that skiing it wasn’t exactly legal. I found YouTube videos of a few people making some ski turns on Kili under the radar, though, so it was possible. But then there was the expense of flying to Africa. I could potentially fly to Tanzania from Russia after Elbrus to keep costs down. I penciled it in for the end of June.

Last on my planning list was Kosciuszko, in Australia. Dick had left it for last in his quest, but that was one thing I wanted to do differently, since, at only 7,000-plus feet ASL, that summit would be anticlimactic. It also didn’t have snow on it for much of the year, and if it had a season, it seemed to be August and September. Hmmmm, in September 2006 I’d be climbing Everest, so unless Kosciuszko were a stop-off on my way to Nepal—which could cut into my high-altitude focus—it would have to happen in 2005. Note to self: Figure out how to schedule my stonemasonry season so that I have a break between projects to escape to Australia for a secret ski week in early September.

Finally, with a loose game plan in place, it was time to share it with the person I’d promised to share my life with. The one who’d asked, “How are you going to break it to yourself?” when I said I might put skiing on the back burner to get my master’s degree. I was in my office and he was fixing lunch in the kitchen, just down a short hallway. I took a deep breath.

“Hey, Rob,” I hollered. “I have a crazy idea. I think I’m going to ski the Seven Summits.”

Silence.

Just when I thought he must not have heard me, he poked his head through the open doorway and smiled. “Your passport sure will be full,” he said.

“Do you want to come with me?”

“I don’t know, but make sure you invite me for Everest. I’ve always wanted to ski that one.”