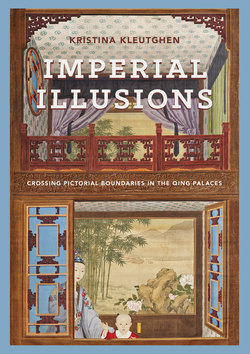

Читать книгу Imperial Illusions - Kristina Kleutghen - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеdrastic changes of Beijing’s harsh climate. Despite these near-complete losses, mapping even the few surviving scenic illusions and visual records of lost works illustrates the diversity of spaces in which they could be found (figures I.5a–b, I.6).

Regardless of their current location, scenic illusions must be considered relative to their original place and spatial context, which often can be reconstructed only textually.48 While the primary documentary source for scenic illusion production is the Wish- Fulfilling Studio archives, Qianlong’s poems are the key source for interpreting their meaning. Few of the approximately forty-three thousand poems credited to Qianlong are notable literary achievements, but they demonstrate how these sites themselves sometimes provoked the commissions, and more importantly reveal the personal meanings that he drew from the various sites and their paintings. Although Qianlong almost certainly projected a constructed self-image in poetry, his poems written for and about the architectural sites that contained scenic illusions, as well as those inscribed on or written about other paintings related to them, are consistently more personal than average. In addition, scenic illusions were sometimes commissioned to imitate others produced earlier and installed elsewhere, creating a chain of references and meanings that evolved with time and place and is often only visible in relation to Qianlong’s poetry. The poetry is therefore as inseparable from those sites as the scenic illusions originally installed there, and they function in concert to illustrate what the site meant for Qianlong.

As expected for most perspectival paintings, the space of each scenic illusion resolves only at a single vanishing point. It therefore has only one perfect viewing position, which also implies the presence of the imperial viewer at a particular position in the original space. Consequently, the physical experience of scenic illusions differs from traditional Chinese paintings in two ways. First, Chinese paintings typically prescribed neither a fixed viewing position nor a fixed angle of representation. Second, the portability of most traditional Chinese painting formats, and their transmission through multiple owners over generations or even centuries, indicates that site-specificity played no consistently meaningful role in producing a painting’s meaning for its owner. Through the painting- architecture relationship, which creates visual contiguity, linear perspective creates specificity of sight and site in the holistic viewing experience of scenic illusions.49 For scenic illusions, therefore, recovering the original architectural context and its meaning to Qianlong are essential to understanding how a painting originally appeared and what it meant.

When both versions of Spring’s Peaceful Message are considered specifically in relation to the significance of the Hall of Mental Cultivation, it becomes apparent that the hall, reserved as it was for the imperial residence and offices, was an entirely logical place for the emperor and his chosen successor to be together.50 The surrounding architectural context not only provided the visual frame that helped create the illusion, but, as the place of the emperor’s daily business, also encouraged the mindset necessary for interpreting the meaning of the painting. The hall became the center of imperial governance during Yongzheng’s reign, when he relocated the imperial residence and office suite from the