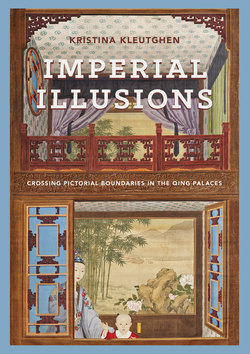

Читать книгу Imperial Illusions - Kristina Kleutghen - Страница 32

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеit is likely that few scenic illusions depicted him; otherwise more would have survived.52 Surviving in situ therefore adds another layer of significance to this rare scenic illusion portrait.

Crossing Pictorial Boundaries

The sheer volume, meticulous detail, and general incorporation of Western techniques in High Qing court painting as a whole encourage the viewer to treat them as realistic and representationally accurate, making it easy to succumb to Qianlong’s pictorial presentation of himself and his reign. Depicted more often than any emperor before him, he adjusted his presentation relative to the various roles he played for contemporary audiences and how he wanted posterity to perceive him, rendering his pictorial identity both discursively and historically mobile.53 Such control over his perceived image is epitomized by the fact that in 1795, after reigning for sixty years, he formally abdicated the throne in favor of his son Jiaqing (r. 1796–1820) as a filial gesture to avoid surpassing his grandfather Kangxi’s sixty-one-year reign. But he retained control of the empire until his death in 1799, not even vacating the imperial residence in the Hall of Mental Cultivation. Yet the depictions of Qianlong’s many accomplishments in paintings do not always measure up against the truth of events during his reign, which laid the foundation for the “destructive nexus of social disintegration and economic decline that would lay waste to so much of Chinese society in the 1800s.”54 Qianlong may not have left the empire better off than when he inherited it, but court painting produced under his patronage suggests otherwise.

Where this carefully constructed image fractures, revealing something of the real man who was emperor, is in scenic illusion paintings. Scenic illusions and their specific messages differ markedly from the rhetoric and propaganda of the emperor’s carefully controlled presentation in the majority of Qing court paintings. Originally installed in some of Qianlong’s most private spaces, scenic illusions offer his personal (and even secret) thoughts on the major issues of his reign, including empire, ethnicity, identity, longevity, and legacy. Although perhaps not all of the original scenic illusions were as intensely symbolic as those that have survived, and some level of imperial rhetoric is always involved, these works are extant largely because of their personal connection to this emperor who had them installed in spaces that were important particularly to him. The specific circumstances of each painting’s production link them to different moments in the imperial biography, a connection strengthened by the relationship of each work to places deeply meaningful to Qianlong, such as his retirement compound and personal art connoisseurship studio, which were preserved even centuries after his death.

Beyond the personal connection to Qianlong in scenic illusions, institutional, perceptual, and semiotic frames that are not immediately visible also affect the paintings and their meanings.55 Scenic illusions were influenced as much by Qing imperial culture as they were by the literature, political events, artistic trends, and popular interests of