Читать книгу Reel Pleasures - Laura Fair - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

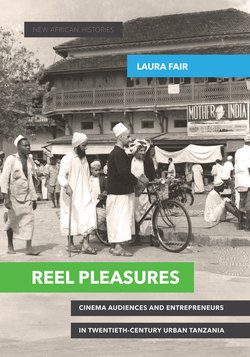

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

FOR GENERATIONS, going to the movies was the most popular form of leisure in cities across Tanzania. On Sundays in particular, thousands of people filled the streets from late afternoon until well past midnight, coming and going from seeing the week’s hot new release. Films from every corner of the globe were shown during the week, but on Sundays, it was always Indian films that stole the show, serving as the focus of these large public gatherings in city centers across the land. In the final hours before a screening, the scene outside the ticket windows could became crazy, as crowds of patrons jostled in desperate attempts to secure the last remaining seats. The meek and gentle often hired agile youth to fight to the front of the line on their behalf, and many later reminisced about the strategies these young men employed to score tickets in the face of such crowds: slinking along walls, crawling between legs, or forming human pyramids capable of catapulting companions to the front. In Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam, two towns with particularly avid fans, demand was so intense that a vibrant black market in cinema tickets burgeoned. At its peak, Dar es Salaam’s population sustained nine different cinemas with a Sunday capacity for nearly sixteen thousand fans, yet inevitably, some were turned away. From the early 1950s through the 1980s, black market tickets for films starring popular actors easily sold for two to three times the ticket window price in the final hours before the show. To avoid the unfortunate fates of those who waited until the last minute to secure a ticket, most people booked their seats well in advance. In towns across the country, many individuals and families even had reserved seats at a favorite theater, which they occupied each Sunday, week in and week out, for years on end. Going to the movies was a central preoccupation for millions and a significant way in which people enjoyed and gave meaning to their lives.

Films became the cornerstone of urban conversations as friends, neighbors, and complete strangers debated the meaning and artistic style of what they had seen on screen. On a continent where literacy was always the preserve of an elite few, films provided a narrative spark that lit debates that quickly engulfed a town. Audiences were never passive. Their active engagement with on-screen texts began inside the theater itself, where youth in the front rows frequently talked back to characters, sang and danced along with lovers in the film, and delivered punches and karate kicks to villains on the screen. Older members of the audience were typically far more reserved, saving their energy for the animated analysis that erupted during intermission and continued to escalate after the show let out. The skills of various actors and actresses were rated, the social worth and deeper meaning of their characters debated. For days, weeks, and sometimes months after a premier, people talked about the message of a film and its implications for their own lives. Generational tensions, the meanings of modernity, class exploitation, political corruption, dance and fashion styles, and the nature of romantic love were just a few of the topics films raised that people avidly analyzed and discussed. As Birgit Meyer has poignantly argued, films become hits because they give form to socially pervasive thoughts, dreams, and nightmares. Movies, she asserts, “make things public”—visible, visceral, material, and thus available for tangible public debate.1 On street corners and shop stoops in Tanzania and in living rooms and workplaces, people engaged both global media and each other as they sifted and sorted, weighed and deciphered, and determined what they did and did not like about the places, the people, and the styles they encountered on the screen. Whether you went to the movies or not, said many, there was no escaping these discussions. For much of the twentieth century, films were the talk of the town in Tanzania.

From the early 1900s, when the display of moving pictures first became a regular feature of urban nightlife in Zanzibar, local businessmen struggled hard to meet audience demand. Not only were they often pressed to accommodate more fans than their venues could hold, they also had to work hard to build dynamic regional and transnational networks of film supply to secure and maintain the enthusiasm of local audiences. A steady crowd could never be taken for granted; it had to be consciously and continuously fashioned. The men who pioneered and built the cinema industry were typically avid film fans themselves as well as knowledgeable entrepreneurs. They kept abreast of the latest global developments in the art, craft, and industry of film and exhibition, and they committed themselves to providing products and services that resonated with local aesthetic demands. The East Africans who ran exhibition and distribution had to keep their fingers on both the local and the global cinematic pulses simultaneously. Building on precolonial trade links spanning the Indian and Atlantic worlds, Zanzibari entrepreneurs in the twentieth century developed networks of global film supply reaching to India, Egypt, Europe, Japan, Hong Kong, and the United States. As a result of their efforts, Tanzanians enjoyed access to a far more diverse range of global media products than most audiences anywhere else in the world.2 Although Indian films were perennial favorites, each generation had different genres and national film styles that caught its fancy. During the colonial era—particularly along the coast—Egyptian musicals were nearly as popular as their Indian counterparts. Elvis, kung fu, and blaxploitation films were favorites of the young, postcolonial generation. Cowboys, from the American Alan Ladd in the 1940s and 1950s to the Italian Giuliano Gemma in the 1960s and 1970s, consistently drew a sizable young, male crowd. Globilization may have emerged in the late twentieth century as a new buzzword in academia, but the transnational movement of goods, ideas, and technologies has long been part of East Africans’ mental and material worlds. And in the case of celluloid, it was Tanzanians who were driving and directing these flows.

This book interweaves the local, national, and transnational. Some chapters offer close-ups illustrating the richly textured experiences of specific audiences and how they reworked particular films to give them meaning in individual and communal lives. Other chapters take a broader view, exploring how audience experiences varied across sociological categories, space, and time. And then there are the panoramic views that situate Tanzania within the context of twentieth-century transnational media flows and global cosmopolitan connections. Often, these local, regional, and global entanglements are brought together in a single chapter to highlight their interconnections. In other instances, such relationships are best revealed through paired chapters, one of which is more ethnographic or temporally and spatially focused, whereas the other tracks change over time. Audiences and entrepreneurs are the central characters in the story. Throughout, cinematic leisure and the political economy are viewed as two sides of the same coin; business and pleasure are intertwined. The changing social, cultural, and political context of exhibition and moviegoing is examined from the early colonial period through the socialist and neoliberal eras, demonstrating the importance of historical and political-economic context for understanding cultural consumption, leisure practices, and the relationship between media and audiences.

Films and moviegoing are the central focus of this book, but the bigger picture reveals much about key issues that have long been at the core of Africanist historiography. Gender and generational tensions and transitions figure prominently, as do states and the politics of development. The social construction of masculinities and the values and characteristics of a “good man” are examined in various contexts and across time. Cities and citizenship are also central. One prominent argument is that cinemas were major nodes of urban social and cultural life, places where urban citizenship was physically and discursively grounded. Theaters brought together young and old; rich and poor; male and female; Muslim, Christian, Hindu, and Parsi; and African, Asian, Arab, and the occasional European. After the show, they took their interpretations of the film onto the streets, where they engaged others in animated debates about the movie and its relevance (or lack thereof) to local lives and society. The most popular films provided viewers with material they could blend, bend, and refashion to speak to their own dreams and desires. The cinema was a space of encounters—a borderland if you will—where Tanzanians engaged with media cultures from across the globe and a diverse range of people from their own towns.

CINEMA, CITIES, AND COLONIALISM

By the late 1950s, Tanzania had more cinemas than any country in eastern and southern Africa—with the notable exception of South Africa—and one of the richest African and Asian moviegoing cultures on the continent. At the end of the colonial era, Tanzania boasted nearly forty theaters, the rough equivalent of all the theaters in French West Africa combined.3 Uganda had only twelve theaters, the Rhodesias (today’s Zimbabwe and Zambia) eleven, and Malawi a mere four.4 Every major Tanzanian town had at least one theater, and many towns had several. Kenya was a far richer colony, but it had only half as many theaters. What accounts for this disparity?

Map I.1 Tanzanian cinemas

The relative degree of urbanization is one important factor that helps explain such variations. Zanzibar—the epicenter from which cinema spread throughout the region at the turn of the twentieth century—had the most urbanized population in sub-Saharan Africa, with more than 50,000 people living permanently in town long before the British Empire claimed the isles.5 The first records we have of cinema attendance indicate that by the mid-1920s, some 2,700 people were going to the cinema in Zanzibar each week, and in the neighboring isle of Pemba, a somewhat smaller but no less impressive 1,500 patrons took in a show weekly.6 According to historian James Burns, in neighboring Kenya and nearby Zimbabwe going to urban cinemas was largely unheard of among Africans at the time.7 In Kenya, less than 8 percent of the population was urban at independence, which partly explains why many Kenyans only began going to the cinema in the 1960s (and many actually never went at all). By the 1960s, one-third of Zanzibar’s population was living in the capital city; by contrast, only 2 percent of all Ugandans were living in Kampala.8 Moviegoing was an urban phenomenon.

Africans’ historical relationship to the city was an equally important factor impacting who went to the show and how often. Tanzanian towns with permanent cinemas in the 1920s—including fairly small ones such as Chake-Chake, Tanga, and Ujiji—existed well before European arrival on the continent: they had permanent populations who considered the town home; many residents who earned their living independent of European employers; and long historical traditions of large-scale, urban, public entertainment at night. When entrepreneurs began offering itinerant shows featuring moving pictures in these towns, crowds welcomed the new arrivals with the enthusiasm they historically extended to dhows pulling into port or caravans marching into a market square.9 Traders brought not only goods but also news, stories, music, dance, and other cultural styles from across the region and indeed the world. Urban residents of these trade-based towns had long been engaged connoisseurs of the cosmopolitan. Moving pictures were a novel form of cultural product in the first decades of the twentieth century, but urban residents appropriated them and made them their own just as earlier generations had done with Islam, the kanga, (cloth) or the msondo and unyago drums. After World War II, the number of cinemas in mainland Tanzania grew exponentially, as up-country entrepreneurs diversified their holdings and invested their capital assets to put their towns on the cinematic cultural map. The fact that cinemas sprang up all across the country illustrates the immense value Tanzanians placed on enjoyment of this cultural form. Local exhibitors delighted in their ability to bring global media products to local doorsteps and also in their capacity to bring their community together and their town to life at night.

All across the continent, people appreciated celluloid spectacle and drama, but the nature of colonialism, capitalism, and urban civic life was not always conducive to the growth of a vibrant moviegoing culture. The literature on screenings offered by colonial film units and mining compounds demonstrates that film and collective viewing were widely appreciated all across the continent.10 But as Odile Goerg’s 2015 book on commercial cinema in colonial French West Africa reveals, audience size varied greatly from town to town.11 It was not that Africans in Dakar, Bamako, or Cape Town did not appreciate this form of leisure as much as their counterparts in Tanga or Ujiji; the issue was having the opportunity to take in a show.

Settler colonies had stringent policies restricting Africans’ access to town. Urban housing was limited, and pass laws and police harassment constrained Africans’ freedom of movement at night. Many towns were also largely colonial creations. The Kenyan towns of Nairobi and Kisumu, for instance, were established by Europeans and relied on a largely migrant labor force. Structurally and administratively, Africans were made to feel as though they did not belong. In Nairobi, they needed a special, government-issued permit before they could buy a ticket to a show. A patronizing list of rules and expectations—detailing a dress code and mode of comportment while in a theater—handed out with the special pass also hampered Africans’ desire to go to a film.12 In the 1950s, as moviegoing blossomed in Tanzania, Kenya was largely under lockdown due to Mau Mau. One can only imagine that in the tense political climate of the Emergency—with more than fifty thousand Kenyans arrested in a single week in Nairobi during Operation Anvil—few were venturing downtown to see what was playing at the cinema. In Zambia and the Belgian Congo too, Africans were prohibited from entering commercial, indoor theaters until just a few years before independence.13 In many cities across the continent, mining compounds, colonial social centers, and church facilities served as the primary venues for Africans’ engagements with film.

Tanganyika’s status as a League of Nations Mandated Territory and Zanzibar’s status as a Protectorate, rather than as formal colonies, gave Africans in these areas a few more protections than those living in Kenya, Zimbabwe, and the Congo, but colonialism was never benign. Across the continent, official colonial opinion was that unless they were required for menial labor Africans belonged in the countryside. Most authorities were convinced that urban Africans were idle or lazy or, worse still, criminally inclined.14 Tanzanian officials were no exception. Efforts to “protect” the sanctity and security of the cities were constant. Africans had to struggle to make their housing legal, and common strategies for earning an independent living in town—such as selling food on the street, raising a few goats or chickens, hawking fish door to door, or selling beer and sex—were criminalized. Offenders were not only arrested or fined but also frequently returned to “where they belonged.” According to Andrew Burton, the capital city of Dar es Salaam was regularly hit by allegedly curative purges to cleanse the city of so-called undesirables.15 But despite official efforts, Dar es Salaam’s population grew, from approximately twenty-five thousand when the British took control from the Germans after World War I to nearly one hundred thirty thousand at the end of colonial rule.16 Colonial authorities had the power to criminalize African urban lives and livelihoods, but clearly, they could not control them.

In Dar es Salaam, Tanzanians also fought for Africans’ rights to go to the movies. James Brennan and Andrew Burton have written masterfully of Dar es Salaam as viewed and imagined by colonial officials and urban planners, where urban space was neatly divided into exclusive racial zones. The city center—where the cinemas were located—was officially outside the “‘African zone,” and any African found there by police after dark was subject to arrest.17 But thousands of Africans went to the cinemas in Dar es Salaam nonetheless, pursuing their pleasures as they desired and giving little heed to administrative imaginary lines. Cinema patrons and owners protested against colonial efforts to keep Africans away from the show, and within a few years of the British takeover of the territory, they had won certain concessions pertaining to Africans’ rights to the city (see chapters 1 and 5). By the 1930s, one of the few “legitimate” excuses Africans could offer to escape arrest when caught in the city center after dark was that they were coming from the cinema or escorting a friend home after a show.18 In other towns, however, African attendance was more constrained. One of the key arguments developed in Reel Pleasures is that cities have their own histories and cultures. Examining regional variations in cinema attendance allows us to see how and why Tanzanians’ experiences in cities differed, as well as how their relationships with urban space changed over time.

The nature of cinematic capitalism in Tanzania also enhanced Africans’ access to the show. All the theaters in the nation were owned by local businessmen. These entrepreneurs invested substantial sums of money building and outfitting their theaters; to make the venture profitable, they needed to sell as many tickets as possible, and many patently rejected administrative calls to restrict African attendance. Equally important, exhibitors lived in the communities where their cinemas operated. They established theaters as a sign of their investment in building social community and bringing people together through a shared appreciation of the arts. Providing attractive and enjoyable entertainment for their communities was a source of great pride. Excluding people because of race or class would have undermined these principles, as well as their bottom lines. At theaters run by industry pioneers, Africans comprised the majority of the audiences from the earliest days.19 In Tanzania, cinemas were independent enterprises, free of the constraints imposed by large exhibition and distribution chains. This too altered their relationship to people in the neighborhood. It was local customers, not distant corporate managers, who determined if a theater would succeed or fail.

Elsewhere, the industry differed. In Dakar and Accra, the first cinemas were owned by Europeans, and they used both exclusive pricing and location to deter all but the most “civilized” from taking in a film.20 Only when ownership and location diversified did audiences diversify as well. In the settler colonies of South Africa, the Rhodesias, and Kenya, white capital dominated the industry, and segregation of facilities and audiences was the norm. By the 1920s, South Africa had more cinemas than the rest of the continent’s countries combined, but it took another thirty years before people of color had regular access to theaters in many towns. The South African exhibition and distribution industries were dominated by a white-owned monopoly, and according to David Gainer and Vashna Jagarnath, even when independent theater owners wanted to offer screenings for mixed or nonwhite audiences they were hampered by the monopoly’s control of films, not to mention the enforcement of apartheid.21 Small-town theater owners had only limited control over the nature of their own shows.

Mobility was central to many Africans’ conceptions of modernity and citizenship. With the end of colonial rule, traversing earlier social, physical, and economic boundaries became a source of newfound delight. Urbanites took great pleasure in walking through previously exclusive parts of town and spending late nights downtown. In Tanzania, urban populations also soared after independence, and going to the movies became one of the premier national pastimes (see chapters 4, 6, and 7).

FILM, SPACE, AND COLLECTIVE PUBLICS

This book builds on a long and rich tradition of African urban social, cultural, and leisure history that emphasizes the vitality and creativity of average men and women and their power to fashion their own lives. Generations of scholars have demonstrated how landless men, disgruntled wives, assertive teens, and even dutiful daughters traveled to towns across the continent in pursuit of particular goals and opportunities and how, despite the odds, they built not only personal homes and individual families but also communities and the social and economic institutions that sustained them. Today’s scholars take as an unspoken premise the fact that Africans shaped the physical and social structures of the urban environment. State officials may have deemed African housing or leisure activities illegal, but rarely did they succeed in keeping people from building, drinking, dancing, selling, playing music, or raising their children in town. This study adds to this vibrant tradition of scholarship by examining how cinemas—as a particular form of urban space—figured in these negotiations between authorities, entrepreneurs, and urban residents over the shape that Tanzanian cities would take. It also demonstrates how individuals and groups utilized cinematic space to create social and intellectual communities and bring joy to their individual and collective days and nights.

Going to the movies provided people with far more than a legal pretext for walking the streets after dark; it gave them a reason to inhabit areas beyond their immediate neighborhoods and a means of establishing both a physical and an emotional bond with the city at large. Walking through the streets on their way to a show with friends, family, and lovers transformed their relationships with urban space, binding people and place together with affective ties. As they laughed with friends on the way to the movies, wiped tears from their eyes outside the theater after the show, or filled alleyways with the sounds of filmic love songs, moviegoers transformed abstract urban spaces into places imbued with sensual, aesthetic, and emotional attachments.22 Theaters—and the urban streets in which they were enmeshed—became invested with tangible, deeply personal meaning. These residual affective bonds between people and place remained long after a fleeting show had passed. In the interviews I conducted for this book, recollections of nights at a favorite theater brought tears of joy and longing to many people’s eyes. Others smiled deeply and said, “That’s where I spent some of the happiest, most meaningful days of my life.” Cinema halls were not lifeless chunks of brick and mortar; they resonated with soul and spirit. They were places that gave individual lives meaning, spaces that gave a town emotional life.

Cinemas were considered by many to be the anchor of the community, and in fact, entire neighborhoods were frequently known by the cinemas in their midst. Urban landmarks, rather than street names and addresses, served to orient one around town. North and south, east and west meant very little to most; far more meaningful directionals in the capital city of Dar es Salaam were the Avalon, the Empire, the Odeon, the Amana, and the New Chox. These were points on urban mental maps that resonated; these were spots that everyone knew.23 In Mwanza, Dodoma, and Mbeya too, a visitor could ask anyone he or she met and be pointed to a family member’s house or a business in the vicinity of the Liberty, the Paradise, or the Enterprise. These were not banal, soulless spaces surrounded by acres of empty parking lots left lifeless after customers walked out the door. These were buildings in the heart of urban neighborhoods, deeply integrated with adjacent homes, schools, mosques, markets, and ports. Disparate urban spaces and people were linked together through the city’s cinematic beating heart.

Across generations, cinemas were central to community formation. It was there, more than at any other place in the city, that a diverse array of a city’s population came into contact. Going to the movies together in no way erased class, gender, race, or religious differences; indeed, at the movies many were forced to acknowledge the immense diversity among people in their town. But through the process of enjoying the same leisure activity and then talking about the same films at work, in the shops, and on the streets, urbanites created “in-commonness,” doing something much bolder than ignoring or eliding difference, creating something shared despite it.24 At the movies, older, established urban residents met on a weekly basis and many new urban immigrants were introduced to people who could help them find housing, work, and scarce materials of all sorts (see chapters 2, 5, and 7). These networks then extended into the larger physical and social landscape of the town, as those who gathered at the cinema returned to their respective neighborhoods and shared their new insights, friends, and connections with others who were sociologically more like themselves.

Boundaries of gender were also negotiated in the interest of attending the movies. In colonial urban Africa, public recreation was largely gendered male; cinemas were sometimes an exception to this general rule. Where cinemas were located, women’s historical relationships with urban space, as well as local cultural and religious norms, were decisive factors affecting female attendance at shows—and not just in Africa but across the globe.25 These issues are explored in detail in chapters 3, 5, and 7, with particular attention paid to how cinemas and cities were perceived across the country as well as how women’s attendance changed over time and varied according to the types of films screened. Typically, however, Sunday shows were family affairs in Tanzania. Everyone, everywhere, regardless of gender or age, attended these shows. Sunday screenings often gave women and children their sole opportunity to venture downtown. Along the coast, theater owners went a step further and responded to women’s clamoring for additional public leisure opportunities by offering gender-segregated, ladies-only (zanana) shows. There was nothing inherently immoral about moviegoing or watching films; it was the possibility of encounters with random men that threatened a woman’s respectability. The ladies-only shows provided women with the opportunity to enter the public realm without jeopardizing their reputations. These all-female matinees, attended by hundreds each week, were a blessing to women who otherwise found few patriarchally sanctioned opportunities to cavort downtown. In Zanzibar, women from the royal family joined with hundreds of less prominent citizens to watch Indian and Egyptian films. Such outings were the highlight of the week. Whether women lived in purdah or not, ladies’ shows gave them a chance to dress up, stroll through town, and make public space their own (see chapters 3 and 5). Thus, even being in purdah did not prevent women and girls from participating in the film-inspired debates that engulfed households, kitchens, and shops.

Cinematic content came to life in the city, further enlarging the networks of people brought and bound together through their engagement with film. One could spot other fans of a favorite star at the market or on the street if they rolled up their pants just like Raj Kapoor did in Awara (Kapoor, 1951) and Shree 420 (Kapoor, 1955); donned a hat like Dev Anand’s in Guide (Anand, 1965); or coifed their hair like Elvis, Geeta Bali, or Pam Grier. In the 1960s, two men who were utter strangers might meet at a shop because they were both in hot pursuit of limited, underground supplies of James Bond underwear with “007” emblazoned on the elastic band. Later, when they met again at a football match or on the city bus, they might nod and acknowledge that they had more in common than the obvious. Men who dared to sport “Pecos pants” (wide bell-bottoms) when such transgressions often resulted in public assaults by members of the Youth League or Green Guards or even a stint in jail signaled, as they walked down the street, not only their love of Guliano Gemma and Italian westerns but also their membership in a larger group of youth at odds with the socialist state’s efforts to control the most mundane aspects of life (see chapters 5 and 7).26 Across generations, fans adopted looks, stances, and language from the movies, but as they did so, the audience they had in mind for their performative engagement was always local. Adopting the latest in cosmopolitan fashion demonstrated their knowledge of global trends and at the same time conveyed their desire to set their own city’s style.

Figure I.1 Jaws Corner. Photo by Sabri Fair, December 2014

Films were also physically inscribed on urban space. Jaws Corner is certainly one of the more enduring examples. Jaws Corner is a well-known baraza, or neighborhood spot where men meet, drink coffee, play board games, socialize, and debate local and world events. This corner, where six major streets intersect in the narrow, winding way of Zanzibar’s famed old town, had long been a major meeting spot. In the 1970s, the area was renamed by a group of young men after they watched the blockbuster hit Jaws (Spielberg, 1975).27 The following day, they painted the first shark on a wall and christened the area Jaws Corner. Forty-some years later, this area is still referred to by that name, and the symbol of Jaws is still regularly repainted on the walls of the buildings to mark the territory.

Jaws Corner powerfully illustrates the complex ways global film products are interpreted, inscribed, and given meaning at the local level. Like audiences across the globe, these young men in Zanzibar were thrilled, scared, and fascinated by Jaws, one of the first movies to successfully employ mechanical stunts. The film became a global cult classic, filling theaters on return runs not just in the United States but also in South Africa, Australia, and Tanzania.28 When Jaws made a two-day repeat run at the Majestic in Zanzibar in 1978, it filled the theater with a midweek crowd of more than twenty-five hundred fans, marking it as one of the most popular Hollywood films ever screened in the isles.29 Some of the young men who established Jaws Corner were fishermen; others swam regularly at the nearby waterfront. They teased and terrified each other, screaming “JAWS!” or humming the infamous tune that foreshadowed the shark’s attack while they worked and played in the water.30 They engaged each other as well as anyone who stopped for coffee or a board game at this busy corner in debates inspired by the film. Was Jaws real or fake? Could a shark really chomp a boat in half? How did those fishermen in the village of Nungwi, known for catching the sharks regularly sold in the market, manage? What mistakes did the old fisherman in the film make that resulted in his defeat? Did Zanzibari fishermen have better strategies for outsmarting the fish?

But these young men who painted Jaws on the walls of their baraza and pestered everyone with their incessant questions about how to defeat a shark also had some big local fish in mind. According to people I interviewed, Jaws was a fitting metaphor for political life in the isles. Like many in Zanzibar in the 1970s, the lead character in the film was a fisherman who had to use his wits to stay alive and remain a step ahead of his adversary. He had to be constantly prepared for an unexpected assault and continually rethinking strategies and new ways to maneuver. Although this character was killed in the end, he provided the knowledge and inspired tenacity that allowed his younger compatriots to defeat the shark.

Many residents and shopkeepers in the neighborhood of Jaws Corner were targeted in the pogroms that wracked the isles after the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution, and relations between actors of the state and neighborhood residents have been tense ever since. The trauma suffered by families, friends, and neighbors in the 1960s was kept from healing by regular assaults, both petty and grand—a situation that has persisted to the present day. The founding members of Jaws Corner were politicized by the initial attacks on their community, and many have been harassed, arrested, and imprisoned over the years. Jaws Corner eventually became synonymous with vocal opposition to the ruling political party. In the topography of urban place-names, it became a landmark, an emblem of a collective resolve to kill the monster who attacked the defenseless. In the 1990s, during the early years of multiparty politics, Jaws Corner was one of the first public spaces associated with the opposition Civic United Front (CUF), and often, there were more posters for CUF in the vicinity of Jaws Corner than there were in the rest of the city combined. For decades, then, Jaws has served as a local metaphor for the relentless, bone-crushing power of the state. But like Quint, the rugged fisherman and less-than-noble hero of the film, those who inhabit Jaws Corner refuse to concede to naked, terrorizing power. They have resolved to defeat the beast or die trying.

CAPITALISM, SOCIALISM, AND RACISM

Examining the role of Tanzanian entrepreneurs in building, running, and sustaining the cinema industry provides a necessary counter to broad-based stereotypes of Africa as a continent in need of external aid to foster economic development. In this book, we see instead men who recognized an opportunity and ran with it. They provided a service their townspeople clamored for and earned a respectable living in the process. Like the wealth of literature on the African “informal economies” that burgeoned in the 1970s and 1980s, this study highlights how local businesspeople mobilized vast local, regional, and transnational networks to meet local demand. By illustrating how Africans have continued to provide for their own most important daily needs—from housing materials to food, clothing, transportation, and leisure—this literature recognizes and gives credit to the plethora of small-scale entrepreneurs who have built the continent.31 Historians have given renewed attention to studies of business, and literatures on the “varieties of capitalism” have burgeoned, but to date, these varieties include few people of color and even fewer from the African continent. Historical studies of business and capital in Africa are necessary to illustrate how economic change has occurred over time, how cultural matrixes impacted business practices, and how individual and communal values structured the accumulation of profit. Neither capitalism nor socialism is a fixed system; both change over time and vary across cultures. And no economic system exists without the individuals who bring it to life. This examination of the cinema industry in Tanzania over the course of the twentieth century allows us to see the concrete ways individuals in specific places and times influenced the forms that capitalism and socialism took, illuminating variations, inconsistencies, and contradictions that force us to rethink the norms presumed by economic isms.

The men who built the exhibition and distribution industries in Tanzania during the first half of the twentieth century were businessmen, of course, but also showmen and civic boosters. Profit was important for them, but equally significant was the desire to enhance the splendors of urban life and show their friends and neighbors a good time. As chapters 1, 2, and 8 elaborate, returns on investment in a cinema were slow to materialize at best, but the personal satisfaction gained by sharing a passion for film and turning others into fans was immense. The admiration entrepreneurs earned by building beautiful, prized cultural institutions was also priceless. Colonial officials gave little attention to enhancing the aesthetic qualities of urban Africa, but the entrepreneurs who built theaters created architectural forms that were not just functional but also attractive, innovative, and inspiring. Cinematic capitalists wed their desire to earn money with an equally powerful desire to endow their community with an effervescent social, cultural, and built environment.

A related component of Tanzania’s cinematic capitalism involved building social ties and feelings of reciprocity between entrepreneurs and people in the community at large. In many parts of Africa, there were generalized expectations that economic power came with communal obligations. Precolonial chiefs accumulated wealth through taxes and labor, but if they wanted to be seen as legitimate political officeholders, they needed to redistribute some of the wealth they amassed; this was often accomplished through periodic feasts or alms to the destitute. This ethos was carried into the twentieth century and applied to capitalists. A “good businessman”—and certainly not all were good—shared his wealth via ritual gifts or endowments to public institutions. In his pioneering work on East African philanthropy, Robert Gregory notes that many of the first libraries, gardens, hospitals, and sports grounds to welcome members of all races in colonial East Africa were financed by gifts from successful businessmen and their families.32 Cinematic entrepreneurs gave to their communities by building places where people came together to find pleasure. They also gave to individuals—and particularly children and youth—by letting them into the shows for free. Cinema seats were a commodity to be sold, but the passions and ethics that guided many entrepreneurs pushed them to share rather than to hoard. Selling a seat was certainly the most preferable option, but an exhibitor made no money by letting a seat go empty—yet he earned social capital as a good man if he gave it to someone with pleading eyes and empty pockets. In the words of Bill Nasson, who was well ahead of his time in writing about the significance of local theaters to community life in African towns, this was “penny capitalism with a chubby face,” where cinema owners represented family-owned businesses deeply integrated into the social fabric of urban neighborhoods.33

Figure I.2 Sultana Cinema in Zanzibar, c. 1953. Photo by Ranchhod T. Oza, courtesy of Capital Art Studio, Zanzibar

Situating the business history of exhibition and distribution in Tanzania within a larger context highlights that there was nothing inherently generous about the cinema industry at large; the varieties of capitalism that permeated the business varied immensely across the globe, the continent, and even within Tanzania over time. In the United States, exhibition, distribution, and production became a vertically integrated industry dominated by a small oligarchy of players in the 1910s and 1920s. Indeed, five large monopoly producer-distributor-exhibition chains controlled 75 percent of box office receipts in the nation by 1930.34 In Britain, the industry was not quite so integrated, but three major exhibition circuits (Gaumont, ABC, and Odeon) controlled the rights for the first-run releases of all the major studios.35 In Australia and South Africa, vertical integration of distribution and exhibition also held sway. In South Africa, the industry came under the monopoly control of Isador William Schlesinger, an American-born Jewish immigrant who relocated to Johannesburg in 1894. Schlesinger made a quick fortune in insurance, real estate, and citrus before turning his attention to building an entertainment empire that eventually included film production as well as print and broadcast journalism.36 In 1913, Schlesinger began buying up South African theaters. He then moved to consolidate the seven independent suppliers of film in South Africa into one organization in which he was the dominant partner.37 He continued the process of centralizing the industry through the 1940s. According to David Gainer, by the time of World War II Schlesinger controlled the first-run release of nearly all the major British and American studios in South Africa; in addition, he owned the vast majority of the most lucrative theaters in the country and had exclusive distribution contracts with all but twenty of the four hundred cinemas outside the major metropolises.38 He also made valiant and repeated efforts to monopolize distribution across the entire African continent.

In South Africa, independent theaters and film importers had no chance against the economic and political power exercised by Schlesinger’s monopoly. He made a sport of forcing men out of business if they dared challenge his power to determine what films they screened or the terms of their rent.39 According to Gainer, if an exhibitor ever dared to show a film provided by an independent importer or did not follow the screening schedule set by Schlesinger, he would be “starved” of product until he left the business. Others were denied films because they dared to purchase new projectors from someone other than Schlesinger, who dominated equipment sales in South Africa as well.40 Even two of the major powerhouses from Hollywood—Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and 20th Century Fox—fought lengthy, costly, and largely unsuccessful battles to break Schlesinger’s monopoly. By the late 1930s, both studios capitulated to Schlesinger’s terms, finding it more profitable and easier to work with him than against him. Together, “The Big Three” came to control 90 percent of the South African market, leaving little room for importers of films from India, continental Europe, or elsewhere.41 The monopoly capitalism and vertical integration of the Gilded Age was on full display in the cinema industry in many corners of the globe.

But the monopoly model was not the only way to organize the industry. Denmark, for one, took an aggressive stance against vertical integration, legally banning related practices in 1933.42 There, distributors were explicitly prohibited from owning cinemas. In India too, individual proprietorships held sway. In neither case did the lack of consolidation hinder the development of robust film production and exhibition industries. Actually, India has always rivaled, if not exceeded, Hollywood in terms of the number of films produced. By the mid-1920s, Indians were producing 100 films a year, a figure that grew to 300 per annum by the 1950s and peaked at more than 900 a year by 1985.43 The number of exhibitors, distributors, and producers in India was similarly large. By the late 1940s, there were more than 600 producers actively making films. In the 1990s, the number of producers was beyond count. As film distribution consolidated in the United States, it democratized in India, growing from 11 distributors in the 1920s to more than 800 in the 1940s to over 1,000 by the late 1950s.44 Exhibition has also been historically characterized by independently owned enterprises. In the 1950s, there was just a single vertically integrated production-distribution-exhibition company in India, but it controlled less than 1 percent of the nearly 4,300 permanent cinemas in the nation.45

Given the large number of distributors and independent exhibitors in India, the profits derived from ticket sales were much more widely shared there than in countries where the industry was monopolized by a few key players. The diversity of distributors in India also afforded greater power to exhibitors, giving them more room to negotiate for better films and film-rental terms.46 In India, exhibitors have historically enjoyed the most stable and consistent profits in the industry, whereas in the United States and South Africa, distributors swallowed the lion’s share of earnings. Block booking, a system whereby exhibitors were required to take a large number of low-quality films for the privilege of securing each hit they wanted, was a standard practice in the United States until outlawed in 1948, and it was a common element in Hollywood and South African international contracts for much longer than that.47 Exhibitors worked essentially as the servants of big distributors rather than as autonomous entrepreneurs. Today in India, Denmark, the Netherlands, and a host of other countries, independent theaters screening films from a range of producers and various national cinemas remain an important part of local and national cultural economies. Clearly, political and economic policies shape not only industrial forms and the accumulation of capital but also leisure and cultural options.

The exhibition and distribution industries in Tanzania occupied an intermediary zone between the Indian and American models and changed somewhat dramatically over time as new political regimes, guided by different economic goals, rose to power. During the colonial era, both the exhibition and distribution industries were run by independent, local entrepreneurs. With but a few exceptions, all the theaters in the nation were individually owned and run by local men who lived in the towns where their businesses operated. As in India, the state paid little heed to the development of these small enterprises. So long as the theater owners abided by fire codes and adhered to censorship rules and regulations, the state did little to govern, direct, or restrict how the industry developed. The colonial state considered most small businesses in Tanzania too petty to bother with, and cinemas, shops, fishmongers, and carpenters operated largely beyond the official gaze. Although colonial officials surely noted the large numbers of people streaming in and out of the cinemas each day, they somehow could not even imagine that it might be worth their while to tax admissions or business profits. There was a duty imposed on films as they entered the country, but no official attention was ever paid to what these films earned once imported.

The situation changed radically with independence. Rather quickly, the cinema industry was brought under state control. Movie theaters continued to be individually operated, but the buildings themselves were nationalized, in 1964 in Zanzibar and 1971 on the mainland. In the 1960s, the socialist state became increasingly directive about all aspects of the national economy. The 1967 Arusha Declaration marked the official beginning of the nationalization of key industries, banking, and trade. The following year, film distribution was formally nationalized. The impact this had on film imports and what was seen by urban audiences was less significant than those familiar with socialist film policy in the Soviet Union or Cuba might imagine, but the profits gleaned by monopolizing distribution were enormous (see chapter 8). Net profits recorded by the Tanzania Film Company Ltd. (TFC) grew from just under 400,000 shillings (TSh) two years after incorporation to nearly 8 million in 1985, a twentyfold increase in a fifteen-year period after adjusting for currency devaluations.48 Oddly, the nature of the industry came closest to the American and South African monopoly models of vertical integration under state socialism. Structural changes allowing for a concentration of capital were deemed good for socialism. Meanwhile, political rhetoric vilified cinematic entrepreneurs as bloodsucking, alien capitalists because nearly all the men in the business were of South Asian descent.

The racist rhetoric of the postcolonial era paid no heed to the facts that not all Asians were capitalists and that capitalists came in immense varieties. The South Asians who immigrated to East Africa were diverse in terms of religion, class, caste, and region of origin. There were also huge variations in the relative degrees of economic success they achieved in East Africa. Some rose to become the captains of industry, but others worked as dhobis (clothes washers) whose daily labor earned them little more than their daily bread. As Richa Nagar has pointedly argued, racial stereotypes often erase the class diversity found within the South Asian communities of East Africa.49 Post-colonial racist rhetoric lumped all Asians into the category of dukawalla (petty, conniving shopkeepers) or economic saboteurs, completely ignoring the class and personal diversity within the Asian community: neither all Asians nor all shopkeepers were greedy racketeers.50 The literature on minorities in East Africa tends to emphasize racial antagonisms between Africans, Asians, and Arabs. Fueled by the racism of the nationalist era, the historiography has sought to explain why East African minorities have been stigmatized as “blood enemies,” to quote James Brennan, stereotyped in political discourse and journalistic accounts from the independence era as ruthless exploiters, slave traders, and foreigners who did not belong.51

There were certainly Asians and Arabs who exploited Africans economically or whose actions aided imperial or subimperial conquest. And extrapolating from these cases to entire populations served the political interests of many early African nationalists. Vilifying minorities, political leaders from Zanzibar, Tanganyika, Uganda, and to a lesser degree Kenya were able to craft a common enemy and distract attention from other concerns. This discourse fueled racial antagonisms, hatred, and assaults. In Zanzibar, in addition to the thousands of Arabs who were murdered, the Asian population of the isles dropped from 18,000 to 3,500 due to persistent assaults in the first decade after independence.52 Many initially joined family and friends on the mainland, but after the Acquisition of Buildings Act of 1971 nationalized property, tens of thousands once again felt compelled to move on.

The personal and collective impact of racism directed at Tanzanian Asians was enormous, but it is also only part of the picture regarding Asian experiences in Tanzania. Equally important were the personal bonds and social networks that allowed immigrants to transform foreign soil into home. By and large, cinema owners were not, to use Gijsbert Oonk’s term, settled strangers—people who lived within African communities but not among them and who remained, even after generations, somehow “other.” Cinema owners and managers were individually named and personally known by nearly everyone in their communities. They were recognized for their individual foibles, quirks, passions, and acts of kindness. As critical members of their local social community, they were deeply integrated, not segregated, and perhaps this helps explain why the vast majority of cinema owners remained in Tanzania long after their buildings were nationalized and most of the Asian population had left the country. Like those who fled between the 1960s and the 1980s, these men endured immense personal and communal trauma. They watched as homes and businesses were seized, daughters and sisters were raped and forcibly married, fathers and sons were imprisoned, and most of their family and communal members went into exile. But for reasons that even they have difficulty explaining, they could not leave. This was home.

I refer to the men who built and ran the cinema industry as they considered themselves: Zanzibaris and Tanzanians. This is not to deny their status as minorities descended from immigrants but to emphasize how they worked to build institutions where anyone who wanted it had access to a seat and to foster communities where people mobilized not only around difference but also around what they had in common. The literature on Asian and Arab immigrants and minorities in East Africa is paltry, given the size of these communities and the fact that they have lived in the region for some two hundred years.53 It is also surprising how dominated the literature is by images of othering minority populations. Our failure to fully examine the diversity of immigrant experiences in Africa, combined with the preponderance of studies emphasizing conflict, has granted normativity to the racism of nationalist rhetoric. Reel Pleasures elucidates how South Asian immigrants and their children developed not only businesses but also social and cultural institutions that built bridges rather than divides.

Socialism, like capitalism, is both an ideology and an economic system that exists only because human beings animate it and bring it to life. Socialists, like capitalists, also come in many different colors and stripes. The political economy of the cinema industry changed enormously after independence, but different actors within relevant state bureaucracies and ruling parties had varying interests that were often at odds. These complexities and contradictions are explored in chapter 6 in the context of the state-owned drive-in theater and in chapter 8 where struggles between industry bureaucrats and others are highlighted. The state was no monolith, nor was the party all-powerful. Socialism had different meanings and measures, and individuals invoked the term with particular outcomes in mind. Race also had little bearing on political predilections. There were Asians and Arabs who were staunch socialists and Marxists and many Africans in the postcolonial governments who were neither. Being a self-described Marxist also did not necessarily mean that one disavowed cinematic pleasure or even Hollywood: a leading comrade in the Tanzanian Defense Force was known by his self-chosen nickname, Tony Curtis, and Hafidh Suleiman, a hard-line member of the Revolutionary Council in Zanzibar, adopted the nom de guerre Sancho after a villain he idolized in Italian westerns.54

The study of moviegoing allows us to hear variety in the voices of postcolonial socialists and see the complicated and divergent ways in which rhetoric and reality intertwined. If some of the narratives presented here seem contradictory, that is because they were. The world is messy, and history no less so. You will not find the straight lines and neatly mapped socialist world depicted in James Scott’s Seeing Like a State here.55 Examining postcolonial cinema policy is more like looking through a kaleidoscope. Every time you turn the lens, you see a different image, distinct but entangled in some difficult-to-discern way with the images before and after. Socialists did not all agree.

CINEMATIC MODERNITY AND MOVIEGOING: GLOBAL TWENTIETH-CENTURY PHENOMENON

This book focuses on the issues and practices that made the business and pleasures of moviegoing in Tanzania distinctive, but it is vital to recognize that in many ways the Tanzanian experience was also part of a much larger global phenomenon. All too often, Africa is ignored or marginalized in studies of worldwide developments. The continent is consigned to the “global shadows,” as if Africa were tangential, rather than central, to the unfolding of truly global experiences.56 This exploration of the cinema industry in Tanzania destabilizes historiographies of underdevelopment and depictions of Africa and Africans as always scrambling to catch up to the rest of the world. Instead, we see that Tanzanians’ experiences were actually commensurate with global trends in technological appropriation, the rise of commercial public leisure, and engagement with transnational media flows. From enraptured nights enveloped in the cocoon of a picture palace in the early twentieth century to midcentury evenings in the family car at the drive-in to late-century retreats to the couch to watch a video or DVD on the family television, Tanzanians’ film watching was in step with both the aesthetic and the technological standards of the time.

Films and stars that took other regions of the globe by storm were equally popular with Tanzanian crowds. Charlie Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy delighted silent-movie audiences everywhere. In the 1950s, the superb acting and impeccable production values of Raj Kapoor’s films ensured sell-out crowds not just in India and Tanzania but also in Russia and Turkey.57 By the 1960s, Elvis Presley was the hottest thing around, and youth from Mexico City to Melbourne, Memphis, and Moshi flocked to the theaters to see his latest moves on screen, which they then emulated on hometown dance floors.58 A decade later, Bruce Lee was the world’s leading screen icon among young moviegoers, including those in East Africa. In the 1980s, the disco craze took the world by storm. But from Tanzania to Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong, it was the dance moves of India’s Mithun Chakraborty, who starred in Disco Dancer (Shubash, 1982)—not those of John Travolta or the Village People—that inspired. As Brian Larkin has persuasively argued, twentieth-century media cultures were transnational phenomena with multiple, shifting metropoles.59 We can only understand transnational media by appreciating Africans’ roles in making them truly global.

The mechanical technology of moving-picture display was nearly identical across the world, yet how this technology was negotiated as a social practice was incredibly diverse. Technology is always imbedded both in space and in society. To say that moviegoing was a global twentieth-century phenomenon is not to say that it was the same everywhere. James Burns’s recent book on cinema across the British Empire brilliantly reveals some of the key similarities and profound differences in the cinematic experience during the early twentieth century.60 Likewise, Lakshmi Shrinivas’s House Full and Sudha Rajagopalan’s Indian Films in Soviet Cinemas profoundly destabilize Western moviegoing habits as the norm. A host of factors affected the social practices of exhibition and moviegoing. I situate the Tanzanian experience within this global context.

Figure I.3 Dar es Salaam Cinema ads. Sunday News, May 8, 1966

At the turn of the twentieth century, moving-picture technology was a revolutionary invention. It mesmerized audiences the world over. Inventors in the United States, Germany, and France were all experimenting with different ways of displaying moving pictures in the 1890s, but the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, are generally credited as giving birth to “cinema” with their first public display of moving pictures on a screen in Paris, in 1895. Unencumbered by patents and pushed by demand, the new technology quickly enveloped the globe, as regional artisans and inventors built on and combined various initial designs.61 Photography itself was fairly new, having been refined only in the late 1870s, and many who went to see moving pictures at the turn of the century had actually never even seen a still photograph. The ability to seemingly capture people on film was deemed magic; watching people and objects move on a screen was spellbinding. When editors of the East African Standard ran a two-part article explaining what a moving picture was and how it worked for their English-speaking, literate audience in 1911 and 1912, the obvious assumption was that few of their British readers had yet experienced this novelty themselves. Though itinerant shows were by then somewhat common in caravan towns and ports in Tanzania, isolated British settlers living on rural farms in Kenya could only imagine what such a spectacle was like. The technological mysteries of moving pictures remained unfathomable to many, even for those who had seen films. In 1917, the swadeshi “father of Indian cinema,” Dhundiraj Govind Phalke, made a short documentary, entitled How Films Are Prepared, to educate the public. He included footage from some of his earlier features as well as shots illustrating the physical and technical processes involved in making these films. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Europeans, Africans, and Asians all marveled at this new technology with equal delight.62

Quickly, however, moviegoing grew from an utter novelty to a mass form of leisure and one of the most popular “cheap amusements” found in burgeoning cities across the world. During the first decades of the twentieth century, urban populations exploded, and mass entertainment was born. Initially, the mass in mass media did not refer to a message pegged to the lowest common denominator; it referred to the huge publics that gathered to see a show. Nickelodeons—so named in the United States because of the nominal fee required to go inside—spread like wildfire in American cities in the first decade of the 1900s as millions of new urban immigrants flocked to the show.63 A similar phenomenon could be found in China, Japan, Thailand, Iran, Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia, Lebanon, Singapore, Jamaica, and India.64 By the time of World War I, overflowing nightly shows were just as common in Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam. The fact that the first films were silent and thus intelligible no matter where they were shown aided the spread of moving pictures. The standardization of film technology and projection equipment furthered the ease with which films circulated: it made no difference, technically speaking, whether the films imported into Zanzibar were produced in India, France, Japan, or Britain. The cheap cost of entrance—typically just a few pennies—made it possible for the working poor in cities from Calcutta to Chake-Chake and Chicago to indulge in an evening’s delights at the moving pictures.

The thrills and spectacles offered by this new visual medium were not its only draw; equally enticing was the ability to vicariously travel to exotic places and explore new surroundings, to access news and information, and to learn about people and customs different from one’s own. Again, readers must appreciate the limited availability of other forms of mass media at that time. Prior to the 1920s, radio broadcasting was extremely limited even in Europe, and many people in the world did not gain access to wireless transmission or affordable receivers until well after World War II. Newspapers and magazines were relatively inexpensive sources of news and information, but most of the world’s population was not literate, making access to print media irrelevant to most. American journalists frequently referred to movies as “the workingman’s college” and lamented that more people got their knowledge of the world beyond their doorsteps from film rather than newspapers.65 In Tanzania too, the desire to learn about new people and places and see how others lived was one of the common reasons respondents cited when asked why they went to the show. An old Swahili maxim said, “Travel to learn/open your mind.” Film offered a slice of the traveler’s vision to those who never left home.

Movie houses also offered patrons access to modern splendors and delights. Inaugurated in Europe in the 1910s, picture palaces swept the globe in the 1920s as the industry sought to cultivate a “higher-class” audience and distance itself from the urban working classes who comprised the majority of viewers during its first two decades.66 Picture palaces evoked glamour and opulence, encouraging patrons to identify with the dream world on the screen.67 I grew up hearing stories from my great-aunt and great-uncle about their adventures dressing in their finest clothes and taking the streetcar downtown to the Tivoli Theater or the Chicago, while courting in the 1930s. For them, these were rare adventures, and their reminiscences focused on the exotic: the opulent theaters with their gilded ornamentation and antique statuary, as well as the extravagant use of electrical lighting—three thousand bulbs in the marquee that spelled Chicago and the largest chandelier in the world in the theater lobby—all of which was a world away from their working-class tenement and single-bulb daily life. Going to the movies allowed them not only to see films but also to physically and emotionally experience a life of affluence and plush indulgence, if only for a short time.

East Africa’s first picture palace, the Royal, opened in Zanzibar in 1921, the same year that the Tivoli and the Chicago debuted. (See fig. 1.2.) Following global aesthetic standards, Zanzibar’s picture palace encouraged patrons of every class to enter a space where they too were royal. According to Mwalim Idd Farhan, a teacher and musician from Zanzibar who attended the theater in his youth, “The way you were treated at the cinema made you feel proud, like you were someone. Just being in the building made you feel like a Sultan.,” He added, “At home we had no electricity, or even a chair. The cinema was lit up both inside and out, and the chairs were upholstered, something unknown to us Swahili back in those days.”68 The American movie moguls A. J. Balaban and Sam Katz, who operated the Tivoli, the Chicago, and one of the first national chains in the United States, would have been proud of the theatergoing experience in Zanzibar. In the 1920s, they were among the first in the United States to inaugurate an elaborate corporate policy of treating moviegoing patrons as kings and queens, which was part of their effort to attract wealthy and middle-class audiences to the picture show.69 Mwalim Idd recalled that “at the cinema everyone was treated like royalty. You had an usher, like a servant, who politely guided you to your seat. He called you sir or madam, and made certain you were comfortable. Nowhere else were you treated so grand.” The fact that the Royal also boasted box seats for the sultan of Zanzibar’s large extended family and the British resident’s entourage further enhanced the feeling of moviegoers like Mwalim Idd that there, if nowhere else, they were experiencing the same indulgence as the wealthy and powerful.

Prior to World War II, movie theaters were among the rare public venues where working-class and wealthy patrons encountered each other and enjoyed the same entertainments as relative equals. Few places in the world were as democratic in this regard as the United States, where patrons all paid the same price for a ticket and sat wherever they chose—so long as they were white.70 In Britain, India, and Tanzania, theaters—like ships, trains, and other public amenities—were divided not by race but by class. The elite typically occupied the balcony, if there was one, and paid substantially more for a ticket. “Second-class” patrons occupied the rear of the main floor, and the poor sat closest to the screen. Such seating arrangements allowed middle-class and elite patrons to maintain their sense of propriety, while simultaneously giving the poor and working-class patrons the satisfaction of knowing that they were traveling the same journey and arriving at the same destination, for a fraction of the cost. Despite—or perhaps because of—divisions by class within the theaters, cinemas were one of the few public places that brought patrons from residentially restricted neighborhoods and clearly distinct class backgrounds into the same space. Whether the cinema was in Bombay, India, in Bukoba, Tanzania, or in Bristol, England, it was while waiting in the queue for a ticket, milling in the lobby, or buying concessions that many encountered the most diverse cross section of people from the town where they lived.71 Exposure to the novel and foreign—on screen, in the city, and within the crowd—was part of the thrill of any adventure at the cinema during these early years of mass commercial leisure.

Film viewing was a collective form of entertainment, and the collective sense of engagement was enhanced by the fact that it seemed nearly everyone was watching—and then talking about—the same film. Opening day frenzies generate a lot of buzz the world over. But in this regard, the Tanzanian experience diverged from the global standard in several important ways. First, Tanzanian audiences took their obsession with being part of the opening day crowd to the extreme. No one with the means to attend would ever agree to be turned away on opening day. Long-standing coastal social conventions of wanting to claim attendance at the biggest and most elaborate public gatherings—be they weddings, dance competitions, or football contests—parlayed into public excitement for filmgoing. Moving-picture technology was incorporated into a long-established cultural milieu that placed immense social value on being able to say that you were part of the largest social gathering around. Local exhibitors and distributors played with and into these desires; most films were screened for only one day or maybe two. Thus, if you wanted to see a new film, you needed to see it the day of its premier—otherwise, you would likely miss it entirely. People paid close attention to the coming attractions; if a film by an applauded director or featuring a popular star was announced, news quickly traveled through the town. If rumors spread that tickets for the most prized seats were selling on the black market, everyone rushed to the ticket windows to book while they could, rather than risk being left out of the party.

Tanzanian exhibitors and distributors had to innovate on more standard industrial practices in order to meet the demands of these large and insistent audiences. In India, Europe, and the United States, first-run openings at numerous theaters were made possible by the simultaneous release of hundreds of prints of a new film. But in East Africa, importers and distributors could rarely afford to buy more than one print. African ingenuity, agility, and ability to make the most of a limited situation saved the day. Depending on anticipated demand, Tanzanian distributors and exhibitors would agree to release a new film in two to four of the largest theaters in a given town simultaneously. By staggering start times by twenty minutes and employing “reelers”—agile men with well-tuned bicycles who sped reels of film from one venue to the next—multiple theaters could run a premier using a single print. At the time, films were wound on a series of small reels, each of which contained roughly twelve minutes of run time for a given production. Indian films, which were the only ones ever “reeled,” typically consisted of nine to twelve reels. As each reel finished at the first theater, it was quickly rewound and handed over to a reeler, who hopped on his bicycle, raced through town, and delivered it to the second theater in line. The second theater would then send its first reel to the third cinema in the line, after starting the second reel that had just arrived by bicycle from the first cinema. All nine to twelve reels of a film would be sped around town in this way.72 Moving-picture technology may have been somewhat standardized across the globe, but it required the ingenious application of indigenous tools to overcome local constraints when operating in Tanzania.

In most respects, however, Tanzanian exhibition practices were commensurate with global standards of technological sophistication and modernity. Local exhibitors brought talkies, CinemaScope projection, spring-loaded seats, air-conditioning, and stereophonic sound to their theaters as soon as they were able to do so, often within months of an innovation’s debut in New York or London. The latest global architectural trends were also featured at movie theaters in East African towns. Cinematic entrepreneurs consciously built dynamic regional and transnational networks to keep abreast of the world’s latest developments in the art, craft, and industry of film and exhibition, and they were committed to giving local audiences access to the best product they could possibly deliver.

The glamour and sophistication exuded by the film industry accentuated East African entrepreneurs’ innate predilections for using their businesses to project not just films but modernity, elegance, and style as well. Modernity was a prominent discursive and developmental category of the twentieth century, as important in Tanzania as anywhere in the world. But how the modern was defined, measured, valued, and imagined was open to considerable debate. Drawing on a rich Africanist scholarship exploring the contested nature of modernity, successive chapters in this book illustrate how differently positioned historical actors conceived of the modern; how they imagined and gave form to their place within it; and how, to cite Lynn Thomas, they used the term to make political claims for inclusion or articulate visions of “new—often better—ways of being.”73

Figure I.4 Plaza Cinema, Moshi, c. 1947. From the personal collection of Chunilal Kala Savani

SOURCES AND METHODS

My first waged job, when I was thirteen years old, was working as a ticket and concession stand girl at a small local theater. Years of working at this theater clued me in to the fact that a lot more goes on at the show than watching films. This was where uptown girls met downtown boys and relationships crossed the tracks, often behind parents’ backs. Bold young couples sneaked upstairs to the baby cry room—a soundproofed enclosure with seats and a large glass window looking out on the screen—to make out. Teens too young to purchase alcohol found willing buyers among the slightly older men who hung out at the adjacent hot dog stand. Those with cars, tricked-out bicycles, and hot stereos to sell positioned themselves on the streets outside the theater to take full advantage of the crowd. Adults probably socialized and made deals too, but none of us teens paid much attention to them. The owner taught me how to sell a single ticket over and over again, but it was only while doing this research that I came to appreciate how critical such acts of subterfuge were to the economic survival of American small exhibitors. The mysteries of projection were also first revealed to me there, although our projectionist was gruff and rather creepy and deemed us girls unworthy of learning the trade. But the older girl who filled in for the owner each Monday, his sole day off, more than made up for the creepy projectionist. She spiked the orange fountain drink with gin for employees and let us dance in the lobby after the patrons were gone. She also took me to my first rock concert, Bruce Springsteen’s, and later helped me learn how to drive. My job at the theater later spurred me to ask Tanzanian cinema employees not only about the movies they screened but also about the characters they worked with and the people in the neighborhood they got to know from working at the show.

Data gathered from beyond the traditional archive form the bedrock on which this book is built. Interviews turned my attention from the films people went to see to what going to the movies meant and how people made use of films in their own lives. Kiswahili terms such as mshabiki (fan, fanatic), mpenzi (lover), or mteja (addict) were often used by people to describe their relationship both to particular genres of film and to the filmgoing experience in general. A surprising number of Tanzanians went to the movies at least once a week, and many self-described fans went two times a week or more. I also sponsored an essay contest by distributing flyers, in English on one side and Kiswahili on the other, outside schools, businesses, and bus stops. Respondents were able to write on one of eight different prompts. My fantasy was that this exercise would inspire young people to talk to their elders about the past, but in neoliberal Tanzania literate youth scoffed at the paltry prize money I offered. Older people, however, responded enthusiastically, providing detailed descriptions of nights at the drive-in, fashions borrowed from films, and the place of moviegoing in their lives.

Places are containers of memory; as Annette Kuhn has beautifully shown, memories have topography.74 Walking down memory lane might be a cliché, Kuhn argues, but getting people to take such steps is incredibly useful to the oral historian, providing a pathway into the past. In her own study of moviegoing in 1930s Britain, Kuhn found that encouraging respondents in their seventies and eighties to speak of walking to the cinema had the effect of transporting them back to their early years. In the process, films became situated in a larger network of physical, social, and emotional experiences. Setting the scene in this way gave events and facts a context, without which there would have been no purpose for recall. In the United States, nursing homes have recently started making extensive use of music from years gone by to revive the memories of patients plagued with dementia. The sound stirs regions of the brain that trigger physical, mental, and emotional ties to more vibrant times in elders’ lives. My own research revealed that memories of the cinema and moviegoing were surprisingly vivid for many Tanzanians, which I suspect is because such memories activate and draw on so many different parts of the brain. Thinking back to significant films triggered visual, aural, sensual, emotional, and physical recollections for many respondents. Thus, memories of the drive-in made more than one person salivate because the drive-in was intimately connected with a favorite food that was consumed only there. Others began to sing or dance while recalling a particular Egyptian or Indian film. And several cried and many laughed in remembering the antics of a partner, sibling, or age-mate with whom they went to see films. Memories of moviegoing were often powerful because they were not just about a film but also about the emotional relationships that were forged—between families, peers, and lovers—in the process of going to the show. Cinema memories went well beyond celluloid. They were infused with sensuality and affect; they were poignant, sentimental, and nostalgic.