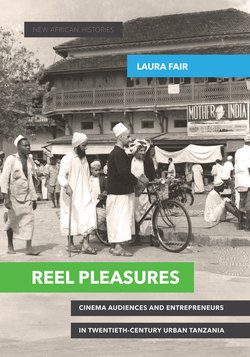

Читать книгу Reel Pleasures - Laura Fair - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

BUILDING BUSINESS AND BUILDING COMMUNITY

The Exhibition and Distribution Industries in Tanzania, 1900s–50s

THE ENTREPRENEURS who built the exhibition and distribution industries in East Africa were businessmen, and like their counterparts the world over, their aim was to turn a profit. But business cultures everywhere are also historically situated and socially constructed. In early twentieth-century East Africa, the capitalist profit imperative was tempered by local cultural norms and religiously sanctioned obligations that made sharing wealth and investing in community corollaries of individual accumulation. Wealth was revered—but all the more so when it was shared. “Big men,” esteemed women, and respected families earned their social status by financing cultural troupes, religious festivals, or large public parties that brought the community together. Privately investing in public infrastructure (such as wells, waterworks, schools, mosques, and hospitals) was another common means of redistribution. Immigrants and the children of immigrants abided by these customary standards as much as the native born did, for this was an effective way to signal their commitment to belonging and to foster social bonds in their new home.1

For the men who built the exhibition industry in Zanzibar and Tanganyika in the early 1900s, one critical factor in evaluating business returns was the degree to which a capital investment helped build a good city and put one’s town on the map. As of the 1930s, only nine towns were able to boast of regular film screenings (see map I.1). These towns were in their infancy at the time—a small fraction of their size and population today—and were built largely of impermanent materials such as mud and stick and thatch. Investing in a building like the Royal in Zanzibar, the Regal in Tanga, or the Tivoli in Mwanza signified a man’s belief in the solidity and prosperity of the future, as well as his commitment to the beautification of a town’s built environment. Cinemas were among the largest and most architecturally innovative buildings in any town, and bringing the latest global media to the community added a touch of cosmopolitan spark to local life. Building a public space where hundreds came together demonstrated one’s willingness to invest in urban civic and artistic culture.

The men who built the industry incorporated elements of preexisting leisure and business customs into cinema’s commercial culture. Like turning a profit, the desire to outdo a rival was a basic business motivation. But in East Africa, the rivalry between theaters was infused with elements from local song, dance, and football competitions. Leisure group competitions were at their most intense when a club had a known competitive rival, and the same was true for cinematic exhibition. Through innovative architectural styles, technological acumen, and the display of the best and most recent films, rival exhibitors continuously strove to win the contest for loyal fans, and moviegoers benefited as a result. This may sound like business competition anywhere, but in the small, face-to-face environment of East African towns, it took on a distinct quality. Business relationships between distributors and exhibitors also incorporated elements of the patron-client relations that infused nineteenth-century business and leisure networks. Building social capital and enhancing a reputation as a trustworthy, dependable individual were deemed far more critical to business success than amassing quick profits. And in the industry in Tanzania, unlike in some other capitalist cultures, the goal was never to eliminate one’s rival but rather to outclass him.

BUILDING HOMES AND INVESTING IN PLACE

The earliest displays of moving pictures were introduced to East Africa by merchants, traders, and sailors traveling the oceans aboard British and Indian vessels. By 1904, if not before, exhibitions of moving pictures had become an exciting and regular feature of urban nightlife in Zanzibar Town.2 Local audiences could never be sure when a man carrying a hand-cranked projector and a few reels of film along with his other goods would arrive, but when he did, word quickly spread.3 Little was required to muster a crowd other than finding a place to hang up a sheet as a makeshift screen: by nightfall, a sizable audience was virtually guaranteed. Given the public’s enthusiasm, what began as an itinerant sideshow quickly grew into a permanent venue with regularly scheduled displays.

Hassanali Adamjee Jariwalla began as an itinerant showman when he was barely twenty and went on to pioneer the formal industry in East Africa. Jariwalla was actually employed by a firm in Bombay as a cloth merchant and traveled by dhow on the monsoon winds taking goods from India to Madagascar and Zanzibar each year. On one trip, according to his grandson, someone in Bombay offered him films and a portable projector to carry together with his other wares,4 and just for fun, he took them along. Soon, he was providing itinerant shows when the dhow he was traveling on reached port, and the enthusiastic welcome that greeted his arrival each season encouraged him to start putting on regular shows. In 1914, he settled permanently in Zanzibar, choosing to make it his new home. That same year, he opened the region’s first semipermanent exhibition hall inside a khaki tent adjacent to the central market, in the neighborhood of Mkunazini. He named the theater the Alexandra, and Zanzibar’s Official Gazette proudly advertised that the latest releases from India, Europe, and the United States could be seen there each night. Within two years, Jariwalla was operating two such venues in Zanzibar, as well as a third in the Upanga neighborhood of Dar es Salaam.5

Business was brisk, inspiring him to draw up plans to transform his exhibition venues from makeshift tents into rock-solid picture palaces. He took what certainly must have seemed a crazy risk, investing his hard-earned savings from the cloth trade in erecting East Africa’s first luxurious cinema—the Royal Theater, which opened in 1921 on the site now occupied by the Majestic Cinema. The Royal was one of the grandest public buildings in Zanzibar and certainly the only piece of architecture of its stature devoted to entertainment.6 Designed by the British resident, J. H. Sinclair, who was trained as an architect, the theater was built in the Saracenic style popularized across the British Empire by those who sought to incorporate so-called Muslim domes and Indian arches into imperial design.7 Sinclair may have dictated the facade, but Jariwalla insisted on the content. The Royal was a large and modern theater on a par with the best operating anywhere in the world at the time. With room for nine hundred seated patrons, as well as box seats and a balcony, the latest projection equipment, and new releases from three continents, the Royal was as impressive as its name implied.8

Figures 1.1 a, b Alexandra Cinema, Dar es Salaam, c. 1916. Images courtesy of the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies Winterton Collection, Northwestern University

Why would a young South Asian merchant risk his savings by sinking everything into an unproven industry and an outlandishly expensive building in Zanzibar? To be sure, the crowds drawn to the moving pictures in the town seemed insatiable, and Jariwalla was clearly of an entrepreneurial spirit. But if it was possible to make people happy showing them silent films inside a tent, why invest something on the order of a million dollars to build a picture palace?9 This was Africa, after all. Wouldn’t a makeshift tent suffice? And when the average weekly attendance was five hundred patrons who paid less than ten cents for each ticket, how many shows over how many decades would it take to pay off the cost of construction, let alone turn a profit? Furthermore, how sure could anyone be in the 1910s that cinemagoing would be an enduring pastime—especially in East Africa, which was in the early, brutal years of imperial conquest? To comprehend the rationale behind building a cinema in colonial Tanzania, we need to see that investments of this type were about much more than monetary profit: they earned proprietors, townspeople, and even colonial officials valuable social and cultural capital.

Figure 1.2 Royal Cinema, Zanzibar, opened 1921 (renamed the Majestic in 1938). Photo by Ranchhod T. Oza, courtesy of Capital Art Studio, Zanzibar

All the men who built cinemas in Tanzania were either immigrants or the children of immigrants, but after settling in Zanzibar or Tanganyika, they invested heavily in developing not just business and commercial networks but also the physical, social, and cultural infrastructure of their towns. Sinking their capital literally into the ground spoke louder than any words could about their commitment to making East Africa home. The architectural history of the region is largely a lacuna, but Robert Gregory estimates that upwards of 90 percent of the cityscape in East African colonial towns—from private homes to markets, courthouses, and schools—bore the mark of immigrant Asian contractors, architects, craftspeople, financiers, and laborers.10 From private homes and shops to public buildings of many types, South Asians played a major role in giving East African towns concrete form. Privately owned buildings offered opportunities to display artistic style, architectural competence, and financial power.11 And cinemas, as monuments to the idea of a collective public sphere, enabled businessmen to demonstrate their commitment to building a beautiful town and a social community as well.

The religious traditions and personal experiences of many South Asian immigrants helped generalize expectations that financial success came with communal obligations. Many early immigrants were from regions prone to drought, famine, and debt. Most had fled because they had few other options. A common trope in the stories of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century immigration is the young man, perhaps barely in his teens, who arrives in East Africa poor and alone. He is saved from abuse and the vagaries of life only by the generous intervention of some kind soul who takes him in; provides food and shelter; gives him a job; and helps him mature into a solid, successful, and respected man.12 In fact, a number of poor immigrant boys became some of the wealthiest and most powerful men in East Africa. And according to individual and communal narratives, they never lost sight of where they came from. Personal experience both inspired and obligated them to help others.

In neither India nor East Africa did the colonial state invest substantially in health, education, or social welfare. Consequently, such obligations fell largely on local communities. South Asians built many formal and informal institutions for fund-raising and communal development; the annual tithe of 10 percent of one’s income collected by Shia Ismailis and Bohora Ithnasheris for communal investment was but one expression of the strong commitment to social improvement. These acts of philanthropy were, of course, just as fraught with struggles over class, gender, and religious norms and decorum as benevolent donations by the Fords, Rockefellers, or Gateses, but they were still critically important for feeding the hungry, healing the sick, and housing the poor. They also reinforced the conviction that financial success came with communal obligations. Many of the first public hospitals, clinics, and maternity wards in East Africa were built and endowed by successful South Asians, as were some of the best public libraries, the first universities and preschools, sports stadiums, social halls, cultural centers, and public parks. In many instances, these institutions were the first of their kind serving all, regardless of race, religion, or class.13 By making charitable gifts, endowing public institutions, and supporting critical social welfare institutions, individuals and families displayed their wealth, demonstrated their generosity, and enhanced their own social standing as patriarchs and communal elders. Through generous giving, they acquired blessings in the afterlife and social power in the here and now.

Cinemas were certainly not charities like orphanages or medical clinics, but they were nonetheless treasured gifts to the community: they healed souls, opened minds, and provided aesthetic and emotional nourishment for old and young alike. They were, to be sure, businesses first and foremost. But investing in a business enterprise that simultaneously provided a social good was a culturally and historically specific ideal of prudent spending. The men who built East Africa’s cinemas were typically of much more modest means than those who endowed the universities and hospitals, yet in giving what they could, they too sought to endow their communities with cultural facilities. Cinemas were also frequently given over to charity organizations for fund-raising events, further demonstrating the owners’ commitment to philanthropy. As early as 1920, for example, Jariwalla was dedicating the proceeds from various evening shows to charity, a tradition that was followed by proprietors up through the 1980s. Exhibitors were also known to dedicate proceeds to fledgling political parties or public institutions, including the police, schools, and sports teams. In addition, owners and managers frequently allowed local social groups to utilize their facilities rent-free for music, dance, and theatrical shows.14 Charitable donations enhanced the personal and institutional bonds between theaters and the people of the town.

PROJECTING MODERNITY, TECHNOLOGICAL SOPHISTICATION, AND COSMOPOLITAN CULTURAL STYLE

The social capital that came from having a cinema accrued to the community at large as well as to the proprietor. One recurring theme across the hundreds of interviews conducted for this project was that having a cinema of any kind, especially one as beautiful and impressive as the Royal, dramatically enhanced the cachet of a town and, by extension, the prestige of its people. Haji Gora Haji, a poet and film fan from Zanzibar who worked as a sailor on a jahazi (sail-powered cargo boat) in his younger days, described the status he and his crewmates enjoyed as Zanzibaris when they docked in “sleepy backwater towns” along the coast where few had ever witnessed the wonders of moving pictures. The two main islands comprising the Zanzibar archipelago, Unguja and Pemba, boasted six cinemas during much of Haji’s life, making it the equivalent of a regional cultural Mecca.15 Coming from a place with so many cinemas also gave young, economically poor but culturally rich Zanzibaris, Haji among them, artistic license to weave enraptured tales of evenings at the moving pictures for adoring crowds—tales that allegedly inspired others to stow away onboard boats headed to Zanzibar.16

Like picture palaces erected elsewhere in the world, the architecturally opulent theaters built in East Africa were intended to serve as spectacles and as sources of visual pleasure in and of themselves. At a time when the vast majority of Tanzanians lived in mud-and-wattle homes and almost no one had electricity, entering such a monument to modernity thrilled patrons nearly as much as the film entertained them. Going inside these glorious buildings evoked luxury and delight. As one woman said of the cinema in Tanga, “The Majestic was a classy theater, a truly chic, modern space. You felt elegant simply going in. Everyone dressed in their best clothes. You wanted to dress up, dress for your part, because the theater was such an elegant place.”17 Remarking on the Majestic Cinema in Zanzibar, one man recalled, “The building itself was astonishing, truly modern. When it opened our whole neighborhood felt proud. It was really something to be able to say you lived next door to the Majestic.”18 Another man made similar comments about the opening of the Sultana Cinema at the other end of town. “I was only a dockhand at the port, a day-laborer. You know, a man of little consequence or stature,” he said. “But I remember when the cinema opened and my son was so proud. He kept telling all his friends that his father worked next door to the cinema [laughing]. It was like I built the place or something.”19 The general public claimed cinemas as their own and drew personal pride from their affiliation.

The architectural grandeur and names of the cinemas built in the first half of the twentieth century articulated the owners’ perception of their towns’ parity with cultural capitals across the world, as well as their commitment to enhancing residents’ stature as fully engaged cosmopolitans and discerning cultural connoisseurs. Names such as the Globe, the Empire, the Alexandra, and the Metropole captured this sense of global cosmopolitan connection. The name Majestic was given to several picture palaces built along the coast, communicating each benefactor’s sense of the grand, dignified, and aesthetically sumptuous contribution his theater made to the town. Paradise too was a popular name, evoking the heavenly, delightful nature of the experience afforded patrons once they stepped inside. There was also the Regal, the Empress, the Sultana, and the Elite. Proprietors and citizens alike had strong feelings that the names given to local theaters needed to convey the splendor and importance of the buildings and of the people who lived nearby or went inside.20 In the early twentieth century, East Africans who patronized theaters such as the Royal, the Empire, or the Majestic suffered no illusions of inferiority or backwardness, and indeed, the owners and managers of these fine picture palaces did all they could to ensure that the patrons in their towns, no matter how big or small, felt thoroughly “first class” while they were at the show.

The white colonial elites were just as proud to have a theater in their town or territory. The British resident of Zanzibar was obviously inspired by the opportunity to draw plans for the Royal, and he proudly attended the grand opening and made a habit of treating visiting dignitaries to a film. Zanzibar may have been just a small crumb in the great scheme of the British Empire, but it was the only place between Egypt and South Africa with a picture palace in 1921.21 When Jariwalla’s second picture palace, the Empire, debuted in Dar es Salaam in 1929, it was opened by the governor of Tanganyika, who entered on a red carpet to the applause of white dignitaries and the fanfare of the army band. Colonial officials took delight in cutting the ribbons at cinema openings, and press coverage of these events was extensive. Film screenings were also big events for the European community. The Tanganyika Standard covered one such event at the Avalon in Dar es Salaam in 1946. Attended by the governor of Tanganyika, the screening was described as “the most brilliant social function held in the center of town for many years.”22 A few years later when the Avalon was refurbished, the mayor spoke at the grand reopening, noting how venues like the Avalon provided him and others with an immense sense of civic pride. White journalists frequently emphasized how these modern cinemas served as proof of the tangible rewards of colonial development

Figure 1.3 Christmas/New Year’s greeting card from colonial Zanzibar. From the personal collection of Asad Talati

Tanzania exhibitors continually strove to enhance the physical pleasure of patrons and improve the associated pleasures afforded to passersby. Jariwalla’s first effort to update his khaki tents in Zanzibar came in the form of Cinema ya Bati, a permanent structure built of corrugated tin. The building, which had previously served as a potter’s warehouse, was located on the poor side of town, across the bridge from the central market, in Ng’ambo (literally meaning “the other side”). The building was more permanent than a tent but far from regal. Inside, it was stifling hot during most of the year, and patrons sat on the floor. This was a step up from a tent—but only a small one. Jariwalla knew he and his town could do better than Cinema ya Bati. Thus, he began negotiating with the British resident of Zanzibar and designing plans for the Royal Theater—which would be built just down the street from the colonial court and the home of the resident. As World War I drew to an end and the Tanganyikan mainland fell from German to British hands, he also upgraded his exhibition venues in Dar es Salaam. There, he retired several of his khaki tent venues and moved the projection equipment to renovated buildings renamed the New Cinema and the Bharat (later the Globe). These venues were solid but small, seating only two hundred and three hundred patrons, respectively. Again, his vision was grander than the available architecture. So in 1929, he opened a second picture palace, the Empire, which was built in the Victorian style and was located, like the Royal, adjacent to the commercial and administrative centers of power. The Empire accommodated nearly six hundred patrons and quickly became a node of urban social life in the Tanganyikan capital.23 Like the Royal in Zanzibar, the Empire in Dar es Salaam was a rare public space drawing all ranks of urban society—from the British governor to the average urban resident—into the same place at a time when colonial policy invested heavily in reifying difference and segregating space by race and class.

During the 1920s and 1930s as theaters spread across the land, Tanzanian proprietors worked hard to provide their communities with the most up-to-date and technologically sophisticated experience possible. Few theaters erected in these years were as impressive as the Royal or the Empire, but exhibitors did the best they could given their resources and the size of their towns. Most entrepreneurs began small. The first theaters in every town were tents, converted storerooms, or parts of warehouses. Regional differences in entrepreneurs’ rates of capital accumulation and patrons’ wages and access to cash impacted the timing and extent of upgrades. In Tanga, the tents used for exhibition were replaced in 1929 with two permanent theaters: the Regal Cinema and the Novelty Cinema.24 In Pemba too, makeshift venues were replaced with permanent theaters at that time. By 1931, Pemba had three cinemas, one in Wete and two in Chake-Chake.25 Nearly as soon as synchronized sound films hit the market, Jariwalla upgraded his equipment to accommodate “talkies.” By 1932, both the Royal in Zanzibar and the Empire in Dar es Salaam featured the latest sound films. Three years later, striving to provide the most recent films to the widest public, Jariwalla also upgraded the projection equipment at the Globe to accommodate talkies.26 Keeping up with trends in global technology and style was a hallmark of the cinema industry from its earliest days.

Shavekshaw Hormasji Talati was another Zanzibari cinematic entrepreneur who dedicated himself to bringing the latest cinematic technology and the best in global films to East Africa. Born in Zanzibar in 1889, he retired from the colonial civil service in 1932 and purchased the Cinema ya Bati from Jariwalla. The cinema would provide Talati with a little income after retirement, said his son, and it would help him stay active and engaged in the community.27 After a few years of running the theater, it became clear to Talati that commercial cinema had financial potential, but he also realized that if his business was to grow and prosper, he needed to upgrade to sound and modernize the viewing experience for his patrons. So in 1939, Shavekshaw Hormasji Talati partnered with three other small businessmen from Zanzibar—Abdullah Mohammed Thaver, M. S. Sunjit, and Manilal Madhavji Suchak—and opened the Empire Cinema in Zanzibar, adjacent to the main city market. Being men of fairly modest means, they leased an old stable in a prime location and converted the interior to accommodate four hundred seated patrons. The structure afforded no room for a balcony, but what the partners’ renovation lacked in physical attraction it made up for with cinematic style. The Empire featured first-rate projection and sound equipment and easily competed for customers with the more ostentatious Royal (which had been renamed the Majestic in 1938 when a new owner, Hassanali Hameer Hasham, purchased it from Jariwalla). Making the most of their personal and business connections, the partners quickly gained a reputation for bringing some of the best and most recent films from India, Egypt, Europe, and the United States to the isles. Thaver, for instance, had connections to the Egyptian film world that rivaled Jariwalla’s in India; through the 1960s, Thaver was recognized across East Africa as the source of the best Arabic-language films in the land.28 Actually, it is a wonder that the men were able to secure any films at all, given that they opened their theater and struggled through the first years of operating a new business just as World War II was heating up and global shipping lanes were closing down. But succeed they did, and from the modest beginnings of screening silent films inside a corrugated iron godown where patrons sat on old gunnysacks on the floor, these partners became, over the next two decades, the premier exhibitors and distributors in Tanzania.

Crowds thronged to the Empire in Zanzibar, and many consistently rated it as their favorite cinema, but the owners had grander visions for their town.29 A converted barn simply did not live up to their idea of a modern cinema. The Empire lacked a balcony, which by the 1940s many patrons considered essential for theatrical savoir faire. The absence of a balcony also made it difficult to accommodate the sultan and his family, who wanted to see more movies but required semiprivate seating at public screenings. The high-class films the partners screened also frequently attracted crowds that exceeded the available seating capacity. Thus, by war’s end the owners were organizing to build a larger, more striking venue than the Empire. Ideally, they wanted to build on the site of the former Cinema ya Bati, opposite the main city market, as the spot had sufficient frontage to allow the theater’s architecture to “impress passersby.”30 They also wanted a site that was equally accessible and inviting to Africans, Arabs, Indians, and Europeans and that could accommodate patrons arriving by foot, bicycle, bus, and private automobile. The spot adjacent to the Darajani Bridge would have been perfect, but it was never approved. It took five years of struggle with the colonial authorities to finally agree on a site. This group of showmen refused to build the small, merely functional cinema the administration deemed adequate for Zanzibar; they insisted on erecting a classy, modern theater in a prominent part of town.

While negotiating with planning authorities and other officials, the partners temporarily rented a facility from the colonial government, at the newly constructed Raha Leo Civic Center on the outskirts of town. But from the beginning, this venture was plagued with difficulties and endless professional compromise. The partners were interested in running a proper business that would cater to the local demand for good films and thus turn a profit. The colonial officials, by contrast, tried to control and contain the venture and make it fit with their own visions of a cinema appropriate for Africa and Africans. The partners had to negotiate hard for the right to screen 35 mm commercial films, rather than merely 16 mm educational materials. They also fought administrative efforts to subject films previously screened at the Empire to additional censorship in order to make them “appropriate” for the largely African audience attending Raha Leo. Beyond that, colonial administrators tried to limit the number of nights per week the theater could operate as well as the hours of operation, two additional points on which the partners refused to budge.31 The authorities ended up conceding on nearly every point in these negotiations, but it was exasperating for the partners to have to argue what seemed obvious: if you planned to open a theater or run a business of any type, you had an obligation to give your customers the best available—otherwise, they would look for better options, and you would fail.

The partners ran the cinema at Raha Leo for less than three years because in many ways it remained utterly below the standard they and their public demanded. Opening night foreshadowed the difficulties that would be faced by the partners: shortly after the first film, King Kong (Cooper, 1933), got rolling, the electricity failed, leaving the audience in the dark for more than an hour. The electricity started and then failed, started and then failed, frustrating everyone and potentially damaging new and costly projectors. By the time the power was restored, the crowd was in an uproar, and most people demanded their money be returned. Inadequate electrical service continued to plague Raha Leo throughout the cinema’s remaining years, for the government flatly refused to upgrade the service to the degree required. In addition to losing money every time they had to cancel a show because the electricity failed, Talati and his partners lost face before their audiences. As owners of the Empire with plans to build a new picture palace for Zanzibar, Talati, Suchak, Sunjit, and Thaver had reputations to uphold, so they got out of their lease with the colonial government as soon as possible and forged partnerships with other East African Asians committed to running a proper enterprise.

During World War II, they took what was then a rare legal step for East African businessmen: they incorporated into a limited company, Indo-African Theaters Ltd. This allowed them to protect their families and personal property from liability for any calamities at their theaters, and moreover, it enabled them to seek other investors with capital to build proper, modern cinemas and secure business loans from banks.32 The Zanzibari founders of Indo-African had the entrepreneurial spirit and technological knowledge to advance the cinema industry in East Africa, but as civil servants and small shopkeepers, they lacked the capital to turn their vision into reality. They saw great market potential in the Tanganyikan town of Dar es Salaam, whose population and wealth grew substantially during the war. They approached Kassum Sunderji Samji, a politically prominent and economically successful Ismaili businessman in Dar es Salaam, and offered him a share in Indo-African Theaters. Kassum Sunderji was a known film fan who made something of a habit of attending the cinema after evening prayers. He recognized the need for an additional venue in the mainland capital in the 1940s, so when the partners of Indo-African approached him, he readily agreed to finance their expansion to Dar es Salaam. He funded the transformation of a godown near the port into the Avalon Cinema, which he leased back to Talati and his partners to run.

Figure 1.4 Avalon Cinema, Dar es Salaam, c. 1945. From the personal collection of Asad Talati

Kassum Sunderji was precisely the type of partner the men from Zanzibar needed to expand onto the mainland: he was wealthy and had liquid assets on hand; he was politically connected and well regarded by Europeans, which would help in getting building plans approved; and he was the head of the Ismaili community—a man with a well-deserved reputation for marshaling resources to support public infrastructure and charitable institutions. He personified the rags-to-riches success story that generations of South Asian immigrants passed on to their children and grandchildren. He had left his family of cowherds in India at the tender age of fifteen. Alone and uneducated, he immigrated to Dar es Salaam in the 1890s, where he found work as a shop assistant with a German company. After the war, he opened his own shop, catering to European tastes for cheese, chocolate, alcohol, and other imported goods. He did well financially and politically. He became the president of the Ismaili Council of Tanganyika and was made a count by a close friend, the Aga Khan. He was also appointed as an unofficial member of the Legislative Council by the British governor in the 1940s, another rare honor in those days.33 Having a prominent business, religious, and political leader in their group allowed the owners of Indo-African Theaters to quickly and dramatically expand their operations. With World War II still roiling, their business brought a bit of comfort to the citizens of Dar es Salaam. They opened the Avalon in 1944 with the premier East African screening of Random Harvest (LeRoy, 1942), a film about a British officer’s dual lives and loves induced by shell-shocked amnesia, starring Ronald Colman and Greer Garson; the movie was nominated for seven Academy Awards and represented the high-caliber films the Avalon became known for offering.34

Map 1.1 Cinemas of Dar es Salaam city center

Map 1.2 Cinemas of Dar es Salaam and key neighborhoods

The accolades Kassum received from his connections to the Avalon spurred him to finance the building of two additional cinemas in Dar es Salaam in the 1950s: the Amana and the New Chox. According to his son and his projectionists, Kassum’s affiliation with the Avalon significantly enhanced what was already a very solid reputation, making his name known to even wider segments of the population. The New Chox, like all theaters, was multiracial, but it came to be regarded as the premier cinema for the European community in Dar es Salaam, featuring films that catered to that crowd.35 The Amana, located in the African suburb of Ilalla and adjacent to the football stadium, was the only theater ever built during the colonial era away from a city center. Kassum Sunderji’s goal in financing the construction of the Amana, his son reported, was to provide a lower-priced venue where the urban poor could take in a film. At the opening of the Amana, Kassum argued that cinema was “a necessity of modern times” that should be available to all. Unlike the colonial authorities who built Raha Leo, he was fully committed to providing Africans on the outskirts of the city with a first-class venue, complete with a grand balcony seating 250 patrons. Enthusiasm for the Amana was overwhelming. Attendance at the Wednesday night opening was estimated at more than 1,000, well exceeding the theater’s generous seating capacity of 750.36 And when films were not being shown, the facility doubled as a community center and social hall.

In up-country towns, building a cinema enhanced a benefactor’s self-esteem and buttressed his family’s social value at least as much as it did along the coast. One benefactor, known as Mr. Khambaita, told me with pride about his escapades designing and constructing the Everest, which opened in Moshi in 1953 when he was a mere lad of twenty-nine. “I built the Everest all by myself! It is 60 by 40 feet without any I-beams. Myself I built that! It was quite an architectural feat for the time, and it is still standing in the center of town,” he declared, positively glowing as we spoke.37 From the age of thirteen, when he still lived in India, Khambaita regularly went to the movies, and he became an avid reader of film magazines. During the war, he joined the British service as a construction contractor and was sent to Tanganyika. He had extended family in Moshi and decided to stay after the war, in large part because he managed to convince his elders, who had a transport business and auto repair shop, to invest a small fortune in building the Everest. As a civil engineer, he oversaw the construction of countless buildings in future years, but none made him feel as accomplished as an architect or as proud as a citizen as his work on the Everest. And as for Khambaita’s family, though they had long been well known in Moshi, they acquired regional fame after the Everest opened. “People would come from fifty, even seventy miles, to see a movie on Sunday!” he recalled. “They waited all week for that day! On Saturdays too, farmers would come. Instead of just doing business, they could now bring their families. For women and children who spent nearly all their time on the farm it was wonderful to come to town and enjoy entertainment.”

Figure 1.5 Everest Cinema, Moshi, opened 1953. Photo by the author, 2005

Back in the 1920s, Moshi had had a venue for the occasional screening of silent films, and it acquired a dedicated theater, the Kilimanjaro, by 1940. But like many of the earliest cinemas, that was a small, makeshift affair in a converted garage, and neither the venue nor the films attracted a particularly enthusiastic crowd. This changed dramatically after the war. In the early 1940s, Moshi’s population and economic stature grew as the town became a regional trade and transport hub. This growth in turn spurred local entrepreneurs to invest in new venues for public leisure. The Plaza Cinema opened in 1947, followed by the Everest in 1953 as already described. Thus, in just a few years the seating capacity at Moshi’s cinemas increased from under two hundred to nearly one thousand. The new structures were bold and beautiful, and the proprietors knew enough about film to select movies that would attract a crowd. Khambaita, for example, drove each week to Nairobi for other business and to pick out English films from the stock of Warner Brothers and MGM. He made a similar trip twice a month to Mombasa, where he loaded up his 1-ton truck with general goods in the morning and stopped by the warehouse of a film supplier to pick up Indian films in the afternoon.

Figure 1.6 (above) Playhouse Cinema (later renamed the Shazia), opened 1947, and (right) Highland Cinema, opened 1961, both in Iringa. Photos by the author, 2005

. . .

After the war, the number of cinemas on the mainland mushroomed, as countless people endeavored to elevate the social and cultural status of their up-country towns and shake off their collective status as “country bumpkins” woefully behind their coastal cousins. The vast majority of the cinemas that eventually spanned Tanzania were built in the late 1940s and early 1950s. What is truly astounding is not how widespread the desire for cinematic entertainment was but the degree to which local entrepreneurs were willing to invest in meeting the demand. Of course, many of the cinemas built up-country were substantially smaller than those along the coast, averaging between 450 seats in bigger towns and 250 seats in smaller locales. But then, many of these up-country towns were tiny in comparison to Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam. Bukoba, Mbeya, Musoma, and Shinyanga, for instance, all had urban populations that barely reached three thousand in 1948.38 And though many other towns saw their populations double or even triple between the 1930s and the end of the war, the populations of Lindi, Morogoro, Dodoma, and Moshi numbered only eight thousand each. Nonetheless, families like the Khambaitas—infused with postwar optimism and confident that a cinema would modernize the town and advance its stature as a regional economic, social, and cultural hub—invested their capital in putting on a show.39 And indeed, the bright lights and spectacles of the cinema drew endless numbers to the center of town. Businessmen who invested in building a cinema saw slow returns from ticket sales, but the social capital they amassed certainly exceeded any they might have garnered by opening a dry goods store.

The increasing number of cinemas on the mainland was part of a much larger pattern of urban infrastructural growth across East Africa in the 1940s and 1950s. I was repeatedly told by interviewees that “a lot of people made a lot of money” during the war, and after it was over, many converted their liquid cash into solid investments in property. The downtown areas of urban centers across the region exploded with new commercial, housing, and office construction, and a few people invested in building spaces for public entertainment. In some towns previously considered sleepy backwaters, businessmen either established cinemas for the first time or built up-to-date facilities to replace makeshift theaters that already existed.40 Like early investors along the coast, they hedged their bets and incorporated additional options in their designs. Thus, should a theater flop, which never really happened, the auditorium was constructed so that it could easily be converted into a storage facility or garage. Office suites and retail facilities were also integral components of building designs. Theaters along the coast incorporated office space as well, but the cinema was always the heart of the building and the main reason it was constructed. But in Moshi, Arusha, Mwanza, Iringa, Morogoro, and many other regional towns that blossomed in the 1950s, the pressures for office and retail space were nearly as intense as the demand for modern theaters. Building design thus catered to the multiple demands of the town, while simultaneously allowing investors to diversify their holdings. In these regional towns, the rent earned from office and retail space and small restaurants housed in the same building as the cinema often exceeded the theater proceeds.41

Figure 1.7 Metropole Cinema (later renamed the Shan), Morogoro, opened 1953. Photo by the author, 2005

Asian businessmen and traders generally avoided putting their savings in an established bank at that time, preferring to hide their cash, loan it to others, or pool it in communal savings societies until they had enough to do something substantial.42 Prior to the nationalizations of the 1970s, when Asians in Tanzania and Uganda lost most of their property, real estate investments were considered grounded and relatively secure. They also tended to earn rates of return that surpassed the interest offered by banks.

A fair amount of the capital used to finance the construction boom of the 1950s was acquired from the “illicit” trade and transport of food, clothing, and other items deemed nonessential by colonial authorities in the preceding years. As the British turned their attention and resources toward the war effort, steamers and railways were requisitioned to transport military supplies, materials, and personnel. East Africans’ notions of essential commodities often differed substantially from those of the British and included rice, cloth, matches, and kerosene, all of which were rationed by the state. Private traders stepped in to fill the void between consumer demand and official supply, and soon, alternative forms of transport, supply, and finance moved goods between East Africa and India, Arabia, China, and Japan. The dhow trade in and out of East Africa made a resurgence during the war, and men with lorries moved goods throughout the continent.43 Some dhows docked at established ports, where their cargoes were subject to standard duty rates, but many used smaller landing stations to avoid paying taxes. There, they were met by men with private motor vehicles who transported goods for export and traded them for imports. The risks in transporting goods across the ocean were steep, and the consequences for being caught “smuggling” on land were great; combined with a general shortage of goods, this translated into high black market prices. Individuals willing and able to provide transport earned handsome profits, and by war’s end, they had substantial cash reserves.44 Many of the men who built up-country cinemas after the war earned their capital by operating lorries and buses or by providing spare parts and mechanical services for those who did. Such contributions to the urban built environment served multiple economic, social, and political purposes. They also served to cleanse somewhat dubiously earned cash.

The families who built the cinemas that opened in regional towns were at the center of dense social networks built around the show. Theaters were social institutions that brought life to the town and the region: they were where people went to see and be seen, to share news and gossip, to make connections and solidify potential deals. In the adjacent restaurants, offices, and snack bars or on the benches in front of the theaters, individuals with both problems and opportunities came together to share their thoughts, flaunt their successes, or seek counsel and support. As their hosts, the Khambaitas and other proprietors brought in not only money from ticket sales but also contacts and customers for the families’ other businesses. Through the cinema they not only secured contacts for themselves but shared their knowledge, gossip, and connections with those who came to the show, thus further enhancing their position as people with people.

COMPETITIVE RIVALRY: TECHNOLOGY, FILM, AND STYLE

The entrepreneurs who built and ran East Africa’s cinemas aimed to demonstrate their knowledge of global cinematic and technological trends, as well as their commitment to bringing the best films and facilities they could to the citizens of their towns. Their efforts were spurred in part by innate predilections but certainly enhanced by local business and entertainment cultures, where friends and patrons insisted that proprietors live up to expectations and rivals always pushed them to do just a bit more. For centuries, East Africans had prided themselves on acquiring the latest, the hippest, and the most up-to-date commodities circulating the globe.45 The growth and expansion of the cinema industry created a new venue for expressing this inclination, and changing cinematic technologies, architectural fads, and communal standards kept owners from resting on their laurels. To keep their customers coming back to the show, they had to invest in frequent updates to stay on the cutting edge of their industry. The costs of maintaining a cinema—and thus a reputation—intensified dramatically in the 1950s due to the combined effects of new cinematic technologies, larger amounts of capital in the regional economy, and the entry of new rivals into the industry.

The introduction of sound at the Royal Theater in Zanzibar in 1932, just a few years after the new technology debuted, was symbolic of East African entrepreneurs’ commitment to running world-class theaters and keeping their customers abreast of technological developments. Hassanali Jariwalla did not really need to upgrade to talkies in 1932; in fact, it took most of the 1930s for the majority of theaters in North America, Europe, and India to be outfitted with sound, and the demand for silent films in Zanzibar was showing no sign of decline. At Cinema ya Bati, the antics of Charlie Chaplin remained incredibly popular through the 1930s, frequently drawing sellout crowds. (Charlie Chaplin became such an icon that the term chale was adopted into Kiswahili to denote a joker or clown and is still used today.) Issak Esmail Issak was one of many who recalled the indelible mark Chaplin left on island audiences. On walks during the 1950s, a young Issak noted that his grandfather pointed to the former location of Cinema ya Bati every time they crossed the bridge, proudly proclaiming, “This is where I saw . . . the great epic Raja Harischandra [the first Indian full-length feature film (Phalke, 1913)] and the mustachioed tramp Charlie!”46 Mwalim Idd and Haji Garana were two others who fondly reminisced about flocking to the silent films with other children at Cinema ya Bati, where admission was a mere two cents.47 Asad Talati, whose father purchased the cinema from Jariwalla in 1932, recalled that the silent films continued to attract large numbers of patrons, including many adults, for years. Action and adventure films and the slapstick comedies of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were widely adored, and many people identified Fearless Nadia, a circus performer who became the first female action star of Indian film in Hunterwali (Wadia, 1935), as one of the most popular personalities of that generation.48 But regardless of the ongoing allure of silent films, Jariwalla knew that talkies were the wave of the future, so the proud provider of the first picture palace in East Africa installed synchronized sound as soon as the equipment was available.

Indo-African Theaters Ltd. exemplified entrepreneurs’ commitment to operating with the latest technology and the most impressive architectural style during these early years. In the 1930s, Talati and his partners transitioned from silent films to talkies, and after their initial efforts with the Empire in Zanzibar proved successful, they began pursuing options to build a larger, more modern building in town. After five years of wrangling with the colonial administration to get their permits, Shavekshaw Talati and his partners took out a thirty-year mortgage to build the contemporary theater they felt the Zanzibari public deserved. (See fig. I.2.) The Sultana opened on New Year’s Eve in 1951 with John Payne’s Tripoli (Price, 1950); this was followed on Sunday by Sargam (Santoshi, 1950), starring Raj Kapoor, Rehana, and Om Prakash.49 The crowd at both shows exceeded the available six hundred seats, inaugurating the box office melee that would be a defining feature of filmgoing at the Sultana for the remainder of its existence. Opening ceremonies were graced by the British resident and the sultan, who publicly expressed their gratitude to the investors for adding such a sophisticated institution to local life. Talati also spoke at the opening, saying that it had been his dream for years “to open a theater in Zanzibar as up-to-date as those in Dar es Salaam.”50 But within a year, the Sultana was rendered nearly obsolete by new developments in cinematic technology, requiring the partners to invest even more capital to maintain their status as premier providers of cinematic entertainment, not proprietors who were willing to shrug and tell their clients that last year’s model was good enough.

In 1953, 20th Century Fox released the first CinemaScope picture, accompanied by stereophonic sound. Shot with a new type of lens, CinemaScope inaugurated panoramic filming, which all the major studios then adopted in various forms. The use of these innovative wide-angle lenses allowed for more encompassing views. They also produced an illusion of three-dimensionality, making patrons feel they were part of the action. But to display CinemaScope, one needed new, expensive projection equipment as well as a significantly wider, concave screen. The use of multiple microphones during filming, required to capture a more dispersed subject, led to the development of stereophonic sound. This too required changes to a theater’s sound equipment and numerous additional speakers. Almost immediately after opening their cinema, the owners of the Sultana updated all their equipment, at a substantial cost. And while they were at it, they decided to transform the facade of the building too, eliminating some of the Saracenic elements that had been insisted upon by the colonial administration’s chief secretary, Eric Dutton. In addition, all the original chairs, which had been locally produced, were replaced with spring-loaded, upholstered seats imported from the United Kingdom. Ultimately, more than TSh 400,000 (or over $57,000) was spent renovating the Sultana.51 A commitment to excellence came at a cost.

“Keeping up with the latest” and good-natured competition were key elements of the capitalist ethos permeating East Africa’s exhibition industry. When Hassanlai Hameer Hasham purchased Zanzibar’s Royal Theater from Jariwalla and renamed it the Majestic, he vowed to do all he could to cater to the tastes of “the modern public.”52 With his rivals showing silents in a tin shed or even talkies in a venue half the size of the Majestic, he felt secure in his place at the apex of the local cinematic economy. But by the 1950s, the original picture palace of East Africa was some thirty years old and was now being challenged by the Sultana. He needed to modernize or risk losing customers to the new venue, so he and his manager installed new projection, sound, screen, and seating equipment. Unfortunately, just before the theater was to reopen in 1954, an electrical fire destroyed the entire building, resulting in a loss of at least $140,000 (or more than $1.2 million in 2016 dollars). Undeterred by the calamity, Hassanali Hameer Hasham rebuilt the Majestic from scratch. He redesigned the exterior to reflect the modern era, replacing the earlier Saracenic architecture with art deco elements, and infused the interior with panoramic projection, screen, and stereophonic sound.53 The new theater comfortably sat 750, and it boasted a large, steep balcony with seats for 200.

Figure 1.8 Majestic Cinema, Zanzibar, c.1956. Photo by Ranchhod T. Oza, courtesy of Capital Art Studio, Zanzibar

Letters to the editor in the Tanganyikan press show that by the 1950s, audiences expected theater management to keep them entertained and to offer the latest cinematic technology—and if the managers fell behind, patrons were not afraid to publicly call attention to their failings. Throughout the 1950s, few subjects garnered as much consistent attention in the newspapers as cinemas, films, and the moviegoing experience. Although many articles heralded the opening of new cinemas, the introduction of 3-D films and screens, or expensive renovations, letters to the editor tended to feature complaints about all manner of problems, including broken chairs and “substandard” seating, poor lighting, failed sound, scratched films, delayed start times, and extended intermissions. Audiences in regional cinemas lamented local owners’ reluctance to accommodate CinemaScope and stereophonic sound. Feeling relegated to second-class status vis-à-vis their coastal cousins, they complained bitterly about watching endless repeats of releases made before production studios switched to the new technology or, worse still, viewing new releases but having large portions of the picture flow over the walls, audience, and ceiling. Some owners tried a local, less expensive fix by switching from a 35 mm lens to a 70 mm one, which at least contained the image to the screen, but the projection quality was not nearly as good as CinemaScope. Like the owners of the Sultana, many of the men who owned up-country cinemas had only recently built and outfitted their venues, and they found it frustrating to abandon nearly new projection, sound, and screen equipment—and expensive to replace it. But to protect themselves from charges of incompetence in the national press, they made improvements as soon as they could. Their earnings, their status as patrons of community leisure, and their personal reputations as top-notch businessmen all depended on their willingness to invest in the new technology.

The introduction of CinemaScope projection and stereophonic sound inaugurated something of an arms race in Dar es Salaam. In 1954, the Odeon and Avalon were vying for the title of “the first CinemaScope in East Africa”—a title won by the Avalon and proudly displayed in its corporate logo.54 Less than a decade after opening the Avalon in 1944, the investors in Indo-African spent $56,000 to secure the title. They installed CinemaScope projectors, a new screen, and stereophonic sound incorporating fifteen speakers. They also added upholstered seating, enlarged the legroom between rows, increased the number of balcony seats to 239, and enhanced the ventilation and air-cooling equipment. It took nine agonizing months and another $140,000 to refurbish the Avalon, but the owners were determined to do the job right. They also renovated the facade of the theater to make it look more modern and less like the godown that it once was.55

Figure 1.9 Business letterhead of the Avalon Cinema, Dar es Salaam

Rising to meet the challenge, Hassanali Hameer Hasham, owner of the Majestic Cinema in Zanzibar and the main competitive rival of Indo-African, opened the Empress Cinema in 1954, just a short walk away from the Avalon. Built and equipped at a cost of $420,000 (or roughly $4.2 million today), the Empress was the largest theater in the nation, accommodating 793 patrons—47 more than the refurbished Avalon. The Empress also bragged of the largest balcony in Tanzania, with room for 330 people in widely spaced and deeply terraced rows.56 Of course, the Empress also featured CinemaScope projection, a wide screen for both CinemaScope’s panoramic films and the latest 3-D features, specially designed acoustic ceiling tiles, and multiple speakers for stereophonic sound. According to the European press, however, its crowning glory was a functioning air-conditioning system, indicative of the owners’ determination to assure every aspect of their patrons’ comfort. Even the European population of Dar es Salaam applauded the owners for their attention to detail, comfort, and design.57 Such competition guaranteed access to films and venues that were every bit the equal of midcentury London and Bombay.

By the mid-1950s, adding an adjoining bar and restaurant to a cinema also became de rigueur for a modern leisure venue on the mainland. Despite the fact that many key investors and members of the moviegoing public were Muslim, nearly all the cinemas that were opened or renovated after the war featured a bar. The Odeon was the first theater in Dar es Salaam to serve alcohol, and according to some, this helped it retain its edge even when better pictures were shown at the Avalon and the Empire.58 When the Avalon was renovated, $70,000 was invested in building an adjoining restaurant and two bars. The Empress again one-upped its competitors, including two restaurants in its building as well as a large bar with a parquet dance floor that could be viewed by the patrons in the upper restaurant, adjacent to the cinema’s balcony seating. The bar provided an added enticement for Europeans as well as “modern” urban men, for they could fulfill their gendered obligation by taking the family out to see a movie but then excuse themselves to join others who found the bar more entertaining. It was not uncommon in the 1950s for Muslim men to mix business and pleasure in venues where alcohol was served: being open to others’ social drinking was one of many signs of being modern.

After the war, discourses of modernization circulated widely in East Africa, spurred in part by the imam of the Shia Ismailis, Sultan Muhammed Shah, the Aga Khan I. Regarded as a liberal innovator on many social issues, he actively encouraged Muslim women to pursue advanced degrees, enter the workforce, and abandon the hijab in favor of Western dress. In East Africa, he also inaugurated numerous large-scale investments in public welfare, including health care facilities, educational institutions, and modern affordable housing. He owned numerous prize-winning thoroughbreds, and he was the father of Aly Khan, the third husband of the American actress Rita Hayworth.59 Presumably, he had no problem with the head of the Ismaili religious community in Tanzania, Kassum Sunderji, owning a cinema that featured a bar. Kassum, after all, made his initial fortune selling spirits and wine to Europeans, and that did not keep him from praying each day or donating generously to philanthropic endeavors. Practicality in business matters allowed him to fulfill his religious and social obligations. For those familiar with the competitive rivalry in Tanzanian football, dance, and music groups in the 1950s, the persistent one-upmanship that typified the business dealings of cinema owners surely strikes a chord.60

Of course, business rivalry centered on film and turning out the largest weekly crowd. When tickets for a theater’s movie turned up on the black market or when patrons had to be seated on soda crates in the aisles due to overcrowding, the reputations of the theater’s owners and workers blossomed; they and their public had scored. Authorities repeatedly chastised cinema managers for not working harder with the police to end the black market trade in movie tickets, but those authorities failed to realize how much black market sales augmented prestige.

In Dar es Salaam, the Empire might run Pyaar (Kapoor, 1950), featuring Raj Kapoor and Nargis, against the Avalon’s premier of Guru Dutt’s Baazi (1951), with heartthrobs Dev Anand and Geita Bali. The smaller Azania would counter with an Egyptian film such as Gharan Rakissa (Rafla, 1950) featuring Muhammed Fawzi and Noor el-Hooda, making it a tough choice all around for film fans on Saturdays and Sundays. In 1953, if the Empire in Zanzibar started the week with Ivanhoe (Thorpe, 1952), starring Robert Taylor and Elizabeth Taylor, the Majestic might counter with a tried but true offering of Samson and Delilah (DeMille, 1949), with Hedy Lamarr and Victor Mature. In general, theaters in Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam screened films within six to nine months of their opening in New York or Bombay, though credit, connections, or shipping difficulties sometimes resulted in a delay. The aim was also to open a new film at each screening, but if the new movie on hand could not compete with a rival’s offering, then managers pulled the best from available stock to remain competitive in the battle for the public’s affection and leisure spending. A film such as Samson and Delilah might have been five years old in 1953, but as chapter 4 shows, it had all the elements that Tanzanians prized in movies. As late as 2004, it still held audiences spellbound when screened on ferries running between Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar.

Despite their no-holds-barred rivalry in putting on the best shows and attracting the most fans, competing owners and managers maintained friendly professional and personal relations. If one man’s projectors went down, his rival would offer a spare to tide him over. If someone needed a film because his supplier sent him a dud, his competitor supported him with the best film he had available. Owners, managers, and workers from different theaters conversed frequently, sharing news about business and global industrial developments, national and community politics, local gossip, films, and their children’s studies. They shared laments and commiseration in their common battles with censors, customs officers, and municipal authorities. They invited each other to their children’s weddings and stood by each other at family funerals. And any worker from any theater could get a free seat or two at a rival’s place simply by showing up. All this gave the industry a particular character and appeal. For East African cinematic capitalists, being known as a decent human being was more valuable than pushing a rival to fail.

EARNING SOCIAL CAPITAL IN THE DISTRIBUTION AND EXHIBITION INDUSTRIES

Exhibition and distribution were always and everywhere mutually dependent, but there was no consensus on how the profits from ticket sales would be shared or what the nature of the social, economic, and political relationships between exhibitors and distributors would be like. Tracing the growth and development of exhibition and distribution in Tanzania illuminates how entrepreneurs built industries that supported profitable local businesses while adhering to local social values. Generating profit from the supply of films was, of course, a goal of distributors across the globe. The greatest profits came from screening each film before the widest possible audience, and because distributors and exhibitors had to share box office proceeds, the greatest returns to distributors came when they also controlled exhibition. In the United States and South Africa, the law allowed distributors to consolidate theaters under their ownership and monopolize film supply, making it difficult for independent alternatives to survive. Distributors in these places also maintained control over exhibitors by requiring them to sign contracts for exclusive supply, thereby precluding the showing of others’ films. These contracts typically lasted for years and often committed an exhibitor to accepting certain quantities of low-grade product for every hit provided. Vertical integration, hostile takeovers, “block booking,” and harsh legal contracts may have comprised one way of organizing these businesses, but this model was flatly rejected by industry pioneers in Tanzania.

Though profit making was always the focus of the East African cinema business, it never eclipsed the importance of having a reputation for honesty and doing right by others as a basis for securing credit and making sales: business was a personal, not a contractual, affair.61 There was no monopoly on distribution; rather, a plethora of players—some large, some small—brought in a diverse range of films, and exhibitors had the ability to search for the best product and the best terms. And because there were no excessively large conglomerates controlling exhibition, distributors had to cultivate clients to get their films screened and earn back the money they spent on obtaining prints and securing the legal right to distribute product in a given territory. No one ever starved another man out of business by refusing to give him good films, nor were there any hostile acquisitions. On the contrary, as both distributors and exhibitors the Tanzanians involved in the industry actively helped others get involved. Culturally specific standards of capitalism and manhood demanded that those with means help those without.

From 1900 through the 1950s, the economics of the exhibition and distribution industries had more in common with nineteenth-century East African patron-client relations than with American or South African cutthroat capitalism. In Tanzania, each party had duties and obligations, and business relations were often couched in ethical terms. Several prominent distributors supplied the majority of the films, but they did not monopolize first-run screenings within their own theaters, passing them along to rivals only after most people in town had seen a film. Instead, the aim was for each theater in the nation to be a first-run venue. Only when supply was exceptionally restricted or when a film was so popular that fans demanded to see it again and again did theaters screen shows for a second or third time. Typically it was owners and managers who requested to run a repeat, not a distributor who made the determination as a means of punishing someone with a film that would flop. Profit-sharing arrangements also reflected a recognition that exhibitors and distributors were mutually dependent. Through the 1950s, box office returns were split evenly between them, rather than having 70 percent or more go to distributors as happened where monopolies or oligopolies prevailed.

. . .

When Hassanali Adamji Jariwalla began importing films for display in Zanzibar, he was already a trader enmeshed in networks handling the finance, supply, and distribution of cloth from India across East Africa. The early film import, distribution, and exhibition business was built upon these established patterns. Many of the South Asian traders who immigrated to East Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century started their businesses with no money. Personal connections or membership in a particular religious community secured them an advance of goods with which to begin trading.62 Wealthier merchants advanced goods to trustworthy clients, who paid for the merchandise only after it was sold. Typically, payment was due after thirty, sixty, or ninety days, but “payable when able” agreements were not uncommon.63 In this way, those with little or no capital could get a start in business, and more established merchants and manufacturers could expand their sales territory and thus their profits while simultaneously enhancing their reputations as benevolent patrons. Although Jariwalla was an established cloth trader, he was a novice when it came to importing and showing films. Initially, he took limited risks and invested only a small amount of capital. He purchased several hand-cranked projectors, which were reasonably priced by the 1910s and available from manufacturers in India. A small piece of white cloth or an old boat sail served as the screen at his early shows, and the dark tropical night was the auditorium. Jariwalla was fronted his films by suppliers in Bombay, and he paid for them only after they were screened. He provided projectors to others up-country, to whom he also advanced cloth and films as new supplies arrived. He was reimbursed for the films and cloth according to whatever terms he and his partners agreed on.64

In the 1910s, Jariwalla received his prints from Ardeshir Irani and Abdulally Esoofally, owners of Alexandra Company in Bombay.65 By that time, Jariwalla was showing some fourteen different short films each week, changing his program every Wednesday and Saturday, so he really needed a top-notch supplier.66 He chose well when he partnered with Irani and Esoofally, who were industry pioneers of incredible magnitude. Like Jariwalla, Esoofally had begun with traveling exhibits and then established regular tent venues in Bombay. In 1914, he partnered with Irani, and four years later, they opened a picture palace named the Majestic, at a time when there were only a handful of permanent venues in all of India. Irani and Esoofally purchased their prints—even of American films—from secondhand outlets in Britain that supplied most of the British Empire.67 But Irani was not content with showing foreign films, and he quickly expanded into production. His studio grew into one of the best in India. Irani produced nearly 250 films over the course of his life, including the first Indian talkie, Alam Ara (Irani, 1931).68 Jariwalla did business with the best, and the East African audiences benefited.

The cost of a print was finite, yet returns from that print could expand exponentially in proportion to the number of people who paid to view it. Irani and Esoofally increased their profits by advancing secondhand prints previously circulated in India to Jariwalla, who in turn tried to circulate these same prints as widely as possible within East Africa. To meet the demands of the local cinemagoing audience and satisfy his own need to boost returns, Jariwalla operated several theaters from the earliest days. In the 1910s, he quickly expanded from one khaki tent in Zanzibar to two, with a third in Dar es Salaam. He then sent his films to other tent venues in Pemba, Tanga, Moshi, Tabora, and Ujiji. (See map I.1.) When he upgraded to more solid structures, he replaced his Zanzibari tents with the Royal and Cinema ya Bati and his tent in Dar es Salaam with the Bharat and the New Cinema, eventually replacing these with the Empire. A short while later, he helped his son build the Azania (which would be renamed the Cameo), a modest venue with seats for some three hundred, built on top of what had been the city dump.69 In the 1920s, there was also another small theater in Dar es Salaam, run by Hassanli Nurbhai and located on Kisutu Road.70 None of these cinemas accommodated even half of the patrons served by the Empire, but they remained important venues, permitting Jariwalla to circulate the same films that opened at the Empire before a wider audience. To boost his earnings further, he expanded into potentially lucrative markets in Kenya. A year after he opened the Royal, he began construction on a modest cinema in Mombasa—the Kenya Kinema, which opened in 1923. Four years later, he opened the Alexandra in Nairobi, which he leased to associates to run.71 By the time he opened the Empire in Dar es Salaam in 1929, he was operating six theaters in three territories. For reasons that remain unclear, Jariwalla later pulled out of Kenya as a direct investor, but he continued to be a prominent mentor and supplier for other Asians who entered the industry in subsequent years. As other proprietors came into the market, he rented his prints to them after screening them in his own theaters, beginning the circuit in Zanzibar.

In the early 1930s, Jariwalla updated his two picture palaces, the Royal in Zanzibar and the Empire in Dar es Salaam, to show talkies; although this was great for local audiences, keeping them engaged with the latest developments in the industry, it made his distribution business significantly more expensive. Now, Jariwalla needed to import two types of prints, one featuring synchronized sound and another for theaters that could only show silent films. In the early 1930s, distributors across the world were facing this same conundrum. The best theaters in the largest urban markets updated to talkies by the middle of the decade, but many small-town and rural theaters took years to make the transition. Most studios therefore produced dual versions of their films, one with sound and one without. Jariwalla imported both types of films, beginning his circuit in Zanzibar, where silent films were screened at Cinema ya Bati and sound films premiered at the Royal.

For Jariwalla and many of the entrepreneurs who entered the industry in the ensuing decades, cinema was a side business, a way to indulge and share one’s passion for film and earn a little extra money in the process. But by the 1930s as the East African industry began to take off, Jariwalla partnered with another Zanzibari, Hassanali Hameer Hasham (commonly known as Hameer Gozi, from the Kiswahili ngozi, meaning “skin,” because his main line of business was trading in hides). Hameer harnessed additional networks with producers in India to augment Jariwalla’s supply. These films were screened first at the Royal (renamed the Majestic in 1938 when Hameer bought the theater from Jariwalla) and then sent to Jariwalla in Dar es Salaam, who screened them at the Empire or Azania before releasing them to other exhibitors across East Africa. Ideally, a film would be paid for entirely through screenings at the Majestic in Zanzibar and the Empire and the Azania/Cameo in Dar es Salaam; then, revenue generated through screenings in other men’s venues would accrue as profits. Jariwalla could have consolidated his hold on the industry in the 1930s by building a vertically integrated business along the South African model, but he did not do so. Instead, he supported others getting their start in the industry, including three men who would become major players—and competitors—in the 1940s and 1950s: Hassanali Hameer Hasham, Mohanlal Kala Savani, and Shavekshaw Hormasji Talati. Hameer Hasham later returned the favor, further strengthening the patron-client ties that bound the families together: he appointed Jariwalla’s twenty-one-year-old grandson, Shabir, as manager of the Empress Cinema in Dar es Salaam. Good deeds (and bad) were recalled, repaid, and reinvested over generations.

Figure 1.10 Mohanlal Kala Savani (Samji Kala), founder of Majestic Film Distributors Ltd. and Majestic Theaters, Tanga. Photo courtesy of his son, Chunilal Kala Savani

Mohanlal Kala Savani was an early entrepreneur in the cinema industry in Kenya who began as an importer of five to ten films a year into East Africa and within three decades became the key link in a family-firm chain that distributed Indian films to every corner of the world.72 But like Jariwalla, he started out quite small. He followed his brother from Gujarat to Mombasa in 1918, with only a few shillings in his pocket. Like legions of other young South Asian men at that time, he was deemed trustworthy by someone with capital in Bombay and was employed as an East African agent, receiving imports of flour and dry goods from India and forwarding them across East Africa. By 1925, he had amassed enough capital to start trading on his own. He switched from foodstuffs to textiles and, with a prod from a friend in Bombay, movies too. He had no theater of his own but screened the occasional films that arrived by clearing space in a storeroom near the port. He then passed the films on to those with cinemas, such as Jariwalla, whom he knew because they both dealt in cloth. By 1935, Mohanlal Kala Savani—commonly known as Samji Kala—had saved enough money from his cloth trade to indulge his lifelong fantasy of opening a proper cinema. With advice and support from Jariwalla, he built the Majestic Cinema in Mombasa, which he rented to Jariwalla’s protégé, Hameer Hasham, to run. Although Samji Kala obviously saw potential in the industry, according to his son all his friends thought he was insane for squandering ten years of hard-earned savings on an enterprise dedicated to projecting fantasy and providing entertainment.73 But like others who took the plunge and invested their capital in building a theater when returns were far from guaranteed, he built modestly and in such a way that the seats could be removed and the structure converted into a godown if the cinema failed. In the 1930s and 1940s, Samji Kala focused his energies on the cloth trade; film remained a pleasant diversion but only a modest source of income.

In these early years, box office receipts were split—as they were in India—with most of the proceeds going to the exhibitor. East African exhibitors kept 50 percent of gate takings, and the remaining fifty percent was shared equally between the supplier in India and the middleman who linked Indian suppliers with East African exhibitors. Samji Kala recognized that he could earn significantly more from each print he imported if he controlled more theaters, but he could not expand for several reasons. For one, he was still quite young in the 1930s and did not have the capital to build more than a single theater. Then too, the political and economic situation in Kenya impinged on the development of a vibrant moviegoing culture among the Asians and Africans who were the primary audience for the films he imported. Members of both groups had difficulty freely walking the streets of the city center, especially in Nairobi. In the 1930s, white businessmen, all integrated with the Schlesinger organization out of South Africa, also owned the main cinemas in Nairobi—the Empire, the Capital, and the Playhouse—and restricted Asians’ ability to open other venues. The best that Samji Kala could do was to lease the Empire, along with the Green Cinema next to the New Stanley Hotel, to show Indian films. And the only time when white owners were willing to concede their space to Asians was on Sundays, when Europeans were supposed to be devoting the day to church and family.74 So in Kenya, Sundays were when Indian films were screened and nonwhites went to the show. Only on the eve of independence, in 1960, was Samji Kala finally allowed to open a cinema in Nairobi, the Kenyan city with the largest and most economically empowered population.