Читать книгу Reel Pleasures - Laura Fair - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

THE MEN WHO MADE THE MOVIES RUN

OWNERS WERE not the only ones who accrued social capital from their connections to film. Cinemas were vibrant urban institutions made all the more dynamic by the often larger-than-life characters who brought the shows to life. Managers, ticket sellers, projectionists, and concession stand operators made the buildings hum, and reelers, human billboards, and black market sellers of cinema tickets—occupational categories that were somewhat unique to this part of the cinematic world—added local flare. Entire neighborhoods were known by the cinemas in their midst, and the men from a range of class and ethnic backgrounds who worked at these theaters were regarded by many as local stars. These men drew immense pride from their ties to the cinema and their ability to bring fantasy, drama, and pleasure to others’ lives. Sociability, commitment to community, professionalism, and pride in a job well done were hallmarks of being a good man in early twentieth-century East Africa. And working at a cinema or simply being affiliated in a tangential way allowed men to demonstrate these qualities before a large and appreciative audience.

It was the people who brought the buildings to life, not those who built and endowed them, who held the warmest spots in communal hearts. Their names were known by everybody in town. As one man said of his father, who worked as an usher at the Empire Cinema in Zanzibar in the 1950s, “Everyone knew [him]. If you walked with him you were constantly being greeted, ‘Eh Amir, how are you today? How is the family?’ Cinema was highly valued, so if you worked at the cinema you were popular and people respected you.”1 Many residents could also tell you where cinema workers lived and who their relatives were. Being able to situate these men within the elaborate nexus of the crosscutting social networks of urban life meant that one was better able to connect to power should the need arise for an extra ticket to a sold-out show or should young kids with no money hope to gain entrance by pressuring an “uncle” who worked at the theater to let them in for free.2 But it was not merely the power they exercised over goods in limited supply that brought them prestige: these men were loved because they gave the town a good time. Their charming smiles, twinkling eyes, and willingness to engage anyone and everyone in conversation about matters both grave and mundane added to their charisma. When I think back to my interviews and conversations with the men who ran the shows, engaging, generous, and joyful are the first adjectives that come to mind. At the time I met them, the industry was largely dead and the men were all well past middle age. I can only imagine how contagious their smiles and cheer were when they and the industry they ran were in their prime.

. . .

To make their cinemas a success, most theater owners had to employ from ten to twenty men. From a management standpoint, some positions were clearly more vital than others, but from the perspective of each employee—or even from that of a patron—they were all critical to a truly successful show. Beyond that, cinema workers added verve and vitality to the cast of characters that made up a town, coming as they did from various racial, religious, class, and communal backgrounds. When not at work, they were all interwoven into the wider tapestry of urban life, bringing news of cinematic happenings to their neighborhoods and likewise bringing their friends and families in touch with happenings at the central fixture of urban life.

House managers were certainly at the top of the management hierarchy in terms of responsibility, pay, and communal prestige. Owners often conceded complete control over operations to a trusted house manager, who was paid a respectable but not exorbitant salary to run the theater from day to day.3 Whether the house manager was given the authority to arrange bookings depended on his knowledge of films, his professional relationships with suppliers, and the degree of involvement and control maintained by the owner. But even if the manager was simply given a program of upcoming attractions to bill each week, he still had a lot to do.

Managers typically determined how many times to run a given film, and if a movie flopped, they were the ones who had to scramble to fill its spot with something more enticing. They supervised advertising and made sure that movie posters were prominently displayed. They oversaw the selling of tickets, the collection of money, the keeping of books, and the delivery of daily proceeds to the owner or the bank. When the theater was closed, they ensured that it was properly cleaned, painted, and maintained. If the projector was broken, the sound system blown, the roof leaking, or the electrical lines down, it was the manager who had to locate and organize repairmen, tools, and supplies. The day of the show, managers greeted guests and made them feel welcome—and when throngs tried to push through the doorway, or ticket window lines got totally out of control, they fought to restore order. Often, they were responsible for things that were simply beyond their control. If a film did not run, if patrons were turned away, or if (heaven forbid), the theater had to be closed for major structural repairs, the house managers found themselves in deep trouble. Their greatest fear was not the wrath of the owner but the disappointment of the fans whose needs they could not meet. Because cinemas were central hubs of neighborhoods and towns, a manager whose theater was closed could not go to the market or get a cup of coffee without encountering endless questions about the status of repairs and the expected date of reopening. It was this pressure from mere acquaintances that could produce ulcers or drive a man near to collapse.

Since the men who built the cinemas were patrons not just of the arts but of sundry clients and extended family members as well, house managers were sometimes chosen simply because they were a son, a nephew, a client, or a close friend’s relative who needed a job.4 The patron-client ties that were forged at the cinema were often inaugurated by the poor and needy. Ally Khamis Ally’s relationship with his fictive-kin father is but one of numerous examples. In his sixties at the time of this writing, Ally was still commonly known as Ally Rocky, a nickname he was given as a child because he followed the proprietor of the Wete cinema, a Goan named Rocky, absolutely everywhere; people even teased him about being the Goan’s illegitimate son.5 But Ally ignored the taunts and bore the name of his fictive father with pride. He was fascinated by films, and eventually, his persistence at the theater paid off. While in his twenties, he was bequeathed the management of the Novelty Cinema in Pemba by his fictive father, making him one of the happiest lads in the land. Ahmed Hussein, a poor boy from Dar es Salaam, forged a similarly productive fictive kinship with Hassanali Kassum Sunderji, the eldest son of Kassum Sunderji Samji, who built the Avalon, Amana, and New Chox. Hassanali Kassum Sunderji was nicknamed “Chocolate,” shortened in daily parlance to “Choxi,” because of his love of the treat. His desire for the sweet things in life was indulged by his father, who reputedly allowed him to eat as much chocolate as he liked from the family store. Then, in the 1950s, Kassum Sunderji Samji also built his son a cinema to indulge his passion for film. The cinema was named the New Chox. Ahmed Hussein also had a taste for film, and from the age of ten or twelve, he hung out around the New Chox daily picking up soda bottles, sweeping aisles, or doing whatever chores he could to make himself modestly useful and thus earn admission to the show. At fourteen or fifteen, pesky little Ahmed was finally taken into the projection room, where he would learn his trade. Around town, he then became known as Ahmed Choxi, with his father’s name supplanted by that of his patron and the theater where he was now officially employed.6 As a projectionist, he earned more than double the monthly minimum wage, which was considered quite grand for a young man with only a fourth-grade education. A few years later, he was promoted to house manager of the New Chox, which made his parents exceptionally proud. Both Ally and Ahmed were adopted by men of different class, religious, and ethnic backgrounds from their own. But a love of movies bound them with their fictive fathers for life, allowing both boys to turn a childhood passion into a respectable adult profession.

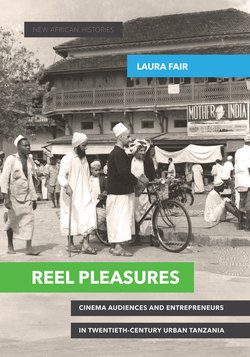

Figure 2.1 Ad for Mother India, Zanzibar Central Market. Photo by Ranchhod T. Oza, courtesy of Capital Art Studio, Zanzibar

House managers were nearly always avid film fans; in fact, most were the equivalent of walking, talking film encyclopedias. Typically, they were gregarious crowd pleasers, and more than one was considered quite the ladies’ man. Their skills were first and foremost people skills. Lacking business and accounting abilities did not necessarily make them bad managers. Being able to please a crowd and woo patrons was more critical to business success. A curmudgeonly accountant or even a manager’s mother could keep the books, but it took a big smile and a big heart to manage one of the central institutions of urban life. In more than one instance, a cinema was handed over to a party boy to manage, with the hope that his natural inclinations could be channeled in a respectable, responsible business endeavor. There were few better jobs for a man who loved to be the life of the party. “Not only did you get to watch films, but you got to meet people all of the time, make people happy and really get to know and talk to members of the community,” said one interviewee, Eddy. “Running a cinema was a business that was also a pleasure! Really it was pure pleasure, but you could earn a living off of it as well.”7

Managers were not the only employees who reveled in the ability to show the town a good time and be at the center of urban social life; nearly everyone I interviewed, from doormen to sweepers, stressed the pleasure and benefits they got from their associations with the show. One man who worked as a gatekeeper from the age of eighteen until he was thirty-five told me, “Really I did it just for the fun. It was just a pastime really, the salary was very little, but it was fun seeing all of the people coming and going. It was a great way to make contacts. I enjoyed it a lot!”8 Many stressed how they got to know everybody in town. “Everyone knew me,” said one man who worked at the Empress in Dar es Salaam, “and . . . many people came and begged me, begged me to help them get tickets to the show.” A man who worked at a theater in Moshi had similar recollections of his power and popularity: “I remember Andhaa Kaanoon [Rama Rao’s 1983 production, starring Amitabh Bachchan and Hema Malini]. If you could get people tickets to that one, oh people will kiss your feet! Oh I had so many friends, so many friends in those days.”9 “Oh yes, and the women,” said another, “they were the highlight of the job! Every beautiful woman in town knew my name.”10 Another doorman who considered himself quite the Romeo in his day echoed those remarks, “The ladies, the ladies were the highlight of the job. All dressed up in their finest and perfumed! And they all knew who I was.”11

To spread the word about their offerings, exhibitors often displayed movie posters at the central market or near a clock tower in the central business district, as well as at the front of their cinemas, and some played music outside their venues in the evenings to draw potential customers’ attention. From the earliest days, movie ads and showtimes were also featured in the English- and Gujarati-language press. But prior to independence, African literacy rates were limited, so if exhibitors wanted to ensure a large crowd, they took their advertising to where the people were and presented the information in a mode designed to communicate with the nonliterate. Thus, human billboards walked the streets of the central business district and the African neighborhoods, ringing bells, honking bicycle horns, or pushing carts festooned with posters and playing gramophone music from an upcoming Hindi film. As casual laborers, they were paid peanuts or simply offered free admission in exchange for their work. Managers did not really need to go to such lengths to garner a crowd, but they were often inundated with pesky young men eager to cement their association with the show: hiring some to walk around promoting movies was simply a way to get them out of the managers’ hair. But to hear the human billboards tell the story, they were as central to the organization as the Jariwallas or Talatis themselves! Their shows in the streets were yet another manifestation of the excitement and revelry the cinema added to urban life; their antics earned them accolades and fond recollections for generations to come.12

Figure 2.2 Human billboards, drawing by Dr. Juli McGruder, 2016. Based on a photo of advertising done by the Majestic theater, Tanga, in Showman 3, no. 3 (1954): 12, published by African Consolidate Films Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

Much less visible but arguably more central to the success of the shows were the projectionists. These men were typically far more reserved than managers, doormen, or walking billboards but no less revered. As Abdul, manager of the Majestic Cinema in Zanzibar, said, “Everyone, everyone wanted to be a projectionist. It was the dream of nearly every young man.”13 This job carried immense prestige because, in addition to being highly paid, it was—as trade publications described—“the heart and soul” of the show. Being a projectionist was highly technical and required a great deal of craftsmanship, mechanical ability, and engineering skill. The knowledge needed for the job increased exponentially over the years as films, projectors, and sound systems became more advanced. Only in the twenty-first century has this trajectory reversed, allowing one person to operate seven or eight multiplex screens with the touch of a few buttons. In the early years, projectors were hand-cranked, and films were rarely more than a minute or two long. Later, typical Indian movies ran for three hours and came on as many as thirteen reels of film, each of which had to run in order and be started as soon as the previous reel reached its end. It was incredibly easy to drop a reel of film or mishandle the take-up reel and end up with a tangled mess on the floor. Heaps of unspooled film were the nightmare of every projectionist but something nearly everyone encountered at least twice—once when he was learning to operate a projector and again when he was teaching the trade to someone else.

Fire was also an ever-present threat. Film was coated with nitrates and highly flammable, and until quite recently, the light that illuminated the pictures came not from a bulb but from a flame burning just behind the celluloid. It was extremely easy for the film to catch fire if it was not in continuous motion. If a film combusted and the operator was inattentive, a fire could quickly get out of control, potentially burning the entire building to the ground. Indeed, the earliest and most elaborate municipal fire regulations often emerged from quite legitimate fears of fire at moving-picture shows—which was as true in Chicago and Birmingham as it was in Zanzibar, Mwanza, and Dar es Salaam. Usually, projectionists were equipped with buckets of water, blankets, or fire extinguishers, and most learned a variety of tricks for putting out a fire before it spread. But the nitrates on the film produced nitric acid when burned, so even if a man managed to save a cinema, burning film harmed his lungs. Fortunately, most projectionists were quite skilled operators, and no one I interviewed had ever seen such a fire.14 A much more common threat was the malfunctioning of the carbon rods used to produce the flame that illuminated the celluloid. Every projectionist I spoke with mentioned how fickle and problematic carbons could be, and they emphasized the skill required to maintain just the proper distance between the two rods to produce the precise amount of illumination required. Readers might recall watching videos of old black-and-white films, where the picture fades to gray or even black and then returns with vivid luminosity: this is what happened if a carbon burnt out and a new one was installed but not properly adjusted.

A young man learned how to run a projector, handle film, and adjust carbons by serving as an apprentice to a skilled projectionist. Every theater had a gaggle of youth eager to learn the trade, and managers often had to set limits on the number of people allowed in a projection booth. A boy given the honor of entry into the projection room would spend years simply watching the professional at work, picking up knowledge as time went along. If he was lucky and trusted, he then advanced to working as a rewinder, using a separate machine to put a finished reel back onto its original spool. If he was paid at all, he might earn sixty-two shillings a month, compared to the four hundred shillings earned by the projectionist, but many times, his only payment was simply the social cachet that came from sitting next to the projectionist or maybe free admission for his siblings and friends.15 The position of assistant projectionist was the next step up the professional ladder, where one earned half as much as a full-fledged operator. The assistant could be trusted to keep the reel running or even start the next reel while the projectionist stepped outside to smoke a cigarette or nodded off for a nap. Being left in charge like that was a huge sign of professional maturation—and a huge responsibility. If a film jumped the sprocket, the gate tension slipped, or a splice broke, the projector could jam or the film could flutter into a pile of spaghetti in no time at all. There was no hiding such mistakes from the projectionist, for he would be roused from his sleep or his smoke by angry cries from the audience lamenting his incompetence or shouting evil things about his mother and the dubious circumstances of his conception.

In many cases, the only way an assistant projectionist could become an operator was through the death or retirement of his boss or through relocation to a town that was opening a new cinema and had no one to run its machines.16 Suresh Solanki began his training in Tanga at the Majestic. Over the course of his five-year apprenticeship, his salary increased from half of what the cinema spent on rat poison, when he began, to one-third of what the full-time projectionists made, when he was promoted to assistant projectionist. His family then took over the management of the Plaza Cinema in Moshi, near Kilamanjaro; Solanki moved from the coast to join them and at last became a full-fledged operator there.17 Had he remained in Tanga, he might never have advanced to the status of a projectionist—a job men coveted for life.

The talents required of a projectionist went well beyond running a machine and included splicing and editing film as well. Considerable skill and a steady hand were required to make a straight and clean splice, and since few projectionists in East Africa owned a splicer, most relied on a simple razor blade to make their cuts. Care had to be taken to join a film so that missing parts were unnoticeable, and sprocket holes had to be aligned to ensure a consistent feed. In addition, emulsion had to be gently scraped off the film and a special cement applied before the two pieces were carefully joined and then held together until the glue dried.18 If not properly done, a splice would result in considerable disruption for the viewers, or it could cause a film to jump the sprocket and unravel, jam, and start a fire or damage the machine. And if a projectionist forgot to use a black marker to cover the sound track on the back side of the film, the audience would also be subjected to annoying audio thumps when the splice fed through the machine. Poorly joined films caused projectionists innumerable headaches. Splicing required adjustments to tension on reels: if the tension was too tight a splice might break, bringing an unwelcome intermission at a key moment of dramatic tension in a film. Cutting and splicing made projectionists the local technical and creative equivalent of film producers.

Censorship of films was routine during the colonial and postcolonial eras, and it was extremely common for certain types of scenes to be deleted, which of course required frequent splicing. In the colonial era, scenes depicting violence, juvenile crime, “unladylike” behavior, nudity, drunkenness, lovemaking, or the ridicule of Europeans—along with nearly a dozen other censored subjects—had to be cut. The particulars changed somewhat during the postcolonial era, but the list of forbidden visual fruit remained long. Given that there was often only a single print of a film circulating in all of East Africa and that Zanzibar, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, and many regional towns all had their own guidelines and censorship boards permitting and excluding different material, every projectionist had to be adept at splicing, joining, and fixing botched jobs done by others.19 The last projectionist to show a film in a region governed by a censorship board had to reinsert all the parts that had been cut before the film was passed to others in the regional circuit. By the time a print had completed the circuit, it was often a cut-and-glued mess. Projectionists did sometimes have fun with splicing, joining miscellaneous cut parts from various films on hand into an original montage of sex, nudity, and violence to entertain fellow workers or friends on rainy days.

A good projectionist was not only an artist and craftsman but an engineer as well. Maintaining and repairing a set of projectors was no simple job, especially in a region of the world where spare parts were nearly impossible to find. Because the first line of defense against costly and time-consuming repairs was proper maintenance of the machines, a good projectionist “coddled his projectors like his babies,” I was told.20 Machines had to be cleaned, adjusted, and oiled daily. Mirrors and lenses needed to be spotless, and the distance between the mirrors and the aperture had to be precise; otherwise, the projection would be distorted. Tensions on rollers, valves, and springs had to be checked and adjusted. Amplifiers needed to be regularly cleaned of cockroaches, since, for some reason, the bugs found them to be extraordinarily suitable places for building nests. But no matter what a man did, his equipment eventually broke down. Consequently, in addition to understanding how his equipment worked, a projectionist had to be able to tell a metalsmith or electrician precisely how to fix it. Simply going to the store to get a new part was out of the question, and if a new one needed to be ordered, it could be weeks or months before it arrived on the next boat. There were no trained projector technicians because there were not enough cinemas in the region to support such specialization. So managers and projectionists had to be jacks of all trades.

Ally Khamis Ally, mentioned earlier, was a precocious child and an avid movie fan, and having weaseled his way into the projection room in Wete as a youth, he delighted in helping the projectionist find both the cause and the cure whenever equipment broke down. When he was a grown man, he managed two cinemas in Pemba and also ran a repair shop fixing radios, sound systems, appliances, televisions, water pumps, small engines, and of course projectors.21 As an engineer, Ally traveled as far as Tabora and Bukoba to help other managers modify and fix their machines. Often managers were forced to take their equipment to a local fundi (repairman), who typically specialized in auto or bicycle repair. “Every time something went wrong you had to hunt around and get it fixed under a mango tree. You know how it is, local, local,” said one manager, Nitesh. “If the guy is good, it will work. If not, your parts are in worse shape than when you started out.” Nitesh’s troubles were compounded by the fact that the theater he ran in the 1980s was the only one in the country that had Soviet projectors, making the odds of finding original spare parts next to impossible. Most theaters had some model of British Kelly projectors, and parts were frequently interchangeable with only slight modifications. One man with an auto repair shop regularly fixed the projectors for the Shan theater in Morogoro, and for him, modifications were no problem: a sprocket was a sprocket, a shaft a shaft. Length and thickness mattered; what it went into did not. In exchange for his services, his family members got complimentary tickets to the movies whenever they wanted.22 It helped that he, his father, and his uncle had all worked in the projection room at the Majestic Theater in Tanga before moving to Morogoro to open the auto repair business in 1954.

. . .

One did not have to be wealthy, highly educated, or technically skilled to benefit from the social capital that came with being affiliated with the show. Small vendors, black marketers, and concessionaires—men who otherwise may have remained small fish in a very big urban pond—became, according to them, central movers and shakers in town. Dozens of men attached themselves to every local cinema. These relationships were mutually beneficial but typically informal and unpaid. Part of the social capital owners and managers acquired resulted from their ability to provide a space where others could create opportunities for themselves. They did not necessarily condone or get involved in all that took place outside their doors, but they tolerated and even welcomed it because it added vitality to cinematic life. The streets outside theaters were humming most of the day and at least half of the night, and the owners and managers generally appreciated the buzz. People gathered there to look at movie posters, share news, drink coffee, and peddle their wares, making the theater a vibrant node of urban life.

Men earned their livings and built their reputations through their affiliations with the show in myriad ways. Those who sold peanuts, fruit, coffee and dafu (coconut juice) outside the theaters made claims about how their connections to the cinema put them at the center of the town’s social life. They had front-row seats to the evening promenade, and no rumor, scandal, or accomplishment passed them by. They also had ample opportunity to chat with men from all walks of life and thus expand their social networks of people with people. The man who sold coffee outside the Cine Afrique in Zanzibar in the early 1990s said that, the area in front of the cinema was an attractive venue for making sales and getting to know folks he otherwise would not encounter. Haji, whose uncle sold fruit and dafu outside the Majestic in Zanzibar, said that the connections his uncle made through the cinema later helped Haji himself secure credit to open a small shop.23 Haji’s family was poor, and even if all his father’s brothers had pooled their resources, they still could not have mustered the capital required to open a regular store and help the young men in their family get started in life. But in the course of a casual conversation outside the cinema one night, Haji’s uncle mentioned the family’s conundrum, and one of the wealthy men who regularly stopped for coffee after prayers offered to supply the money they needed. Over years of mingling with men on these barazas (seats or regular hangouts) in Zanzibar, I witnessed firsthand how the personal connections made there helped men negotiate the familial, legal, bureaucratic, and political trials and tribulations that life threw their way.

Black marketers were another group of men who attached themselves to the show in an informal way that allowed them to earn a living and simultaneously helped the theater earn prestige, for black market sales enhanced a venue’s cachet. Though black marketers often came from poor families and had only a rudimentary formal education, they amassed incredible esteem, and often, they literally held other people’s fates in their hands. A thriving black market for cinema tickets existed in Dar es Salaam from the early 1950s and well into the 1980s.24 In Zanzibar too, avid fans would pay whatever it cost to be part of the opening-day crowd for hot new Indian releases. Markups varied depending on the stars and the films, but patrons were so insistent on seeing these shows that black marketers found they could easily charge two, three, or four times the face value of the tickets they held. I spoke to several men who lived their entire adult lives—building homes, raising and educating their children, and clothing their wives—on nothing other than what they earned from selling cinema tickets on the black market. Khamis told me he could readily make in one evening as much as the monthly minimum wage for an unskilled laborer; he also recalled earning more in a weekend than most people in Dar es Salaam earned in a month. Rashid said he earned between thirty and one hundred shillings a month as a casual laborer in Zanzibar, but he could make two or three thousand shillings in a single day if he held sought-after tickets to a popular film. And it was his earnings from dealing in black market tickets, not his regular wages, that allowed him to build a home. Msafiri claimed that one of his friends earned enough from one movie to put a new roof on his house.25 As Kasanga said of black marketeering, “This was a great job! It was pure joy. It is rare to find work that is both profitable and highly enjoyable. How many lines of work are there where you make a very good living while hanging out with your buddies, watching a movie or two each night, and taking Monday and Tuesday off?”26

Working as a black market dealer in cinema tickets was also a highly prestigious way to earn a living. According to the men who sold these tickets, people respected their ingenuity and adored them for providing a way to see popular shows without having to fight the crowds at the ticket window. Those who wrote to the newspapers complaining about black marketers clearly disagreed, of course, yet the homes of ticket dealers were urban landmarks, almost as well known as the cinemas themselves, said the traders. People dropped by all the time to get tickets for upcoming shows or seek advice on which film to see. Black marketers had many friends, and if they had unsold tickets, they gifted them to those who would otherwise not be able to go. It was like the film Robin Hood, observed one black marketer: “We took only from the wealthy, redistributing cash and tickets to those of us who were poor.”27

Being a black marketer was a skilled job, and like projectionists, these men often learned their trade by watching others or working as an assistant to a professional in their youth. Kasanga began learning the trade when he was in the fifth grade. His school was next to the Cameo in Dar es Salaam, and at the time, the government was in the midst of one of many short-lived, futile efforts to curb the black market. Under the new rules, each patron was limited to purchasing ten tickets, so one of the black marketers enlisted some schoolboys, including Kasanga, to purchase tickets on his behalf. Since the boys were tipped generously for their efforts, Kasanga made a habit of helping the man out and learned from him when, where, and how to buy and sell. When he finished seventh grade, the highest level of schooling completed by most Tanzanians in those days, he took up the trade in earnest, buying and selling tickets on his own. For the next thirty years, that was his principal form of employment.

Black marketers needed to know more than just what seats to buy and how many tickets to hold; they also needed to know about films and stars and how to read trailers and film posters if they were to accurately gauge what they should buy or how much they could charge. Like most everyone in the industry, these men adored film and had been avid connoisseurs since they were children. But black marketers realized there was often a difference between their personal preferences in film and the tastes of the urban crowd. “You had to be skilled and knowledgeable to appreciate which ones would make for good business,” said Taday. “Just because it was a hit in America did not mean it would be a hit in this town. You had to know what people liked.” Dar es Salaam was the best market in the nation by far, and a serious black marketer there might hold two hundred tickets for various films at different theaters each week. Each show was a gamble, but skill allowed a man to hedge his bets. “Sometimes you would lose your money,” said Kasanga, “and on those days we would eat cassava [a cheap starch] without any fish. But other times you would win. Losing and winning was all part of the job. The most important thing was not to lose your capital. So long as you kept your capital safe it was all ok.”28 Typically, he added, he had most of his tickets sold before the day of the show. If not, on show day he went down to the theater, where people would fight to get their hands the few remaining tickets. Khamis preferred the presales to the frantic scrambles in the final minutes before the show; he recalled having to buy a new shirt after the debut of The Rise and Fall of Idi Amin (Patel, 1980) because the crowd outside the Avalon was so frantic for tickets that people tugged at him until his shirt was in tatters.29 Few men in Dar es Salaam had the honor of being fought over, and it was a testament to his knowledge and skill that he had tickets to such a popular show.

Anything the censors attacked or tried to ban also became an instant hit with the urban crowd and was likely to be a sure winner for black marketers. In 1949, No Orchids for Miss Blandish (Clowes, 1948) was banned by some but not all local censor boards in Tanganyika, resulting in specially organized bus excursions from one town to the next for fans anxious to see the banned gangster film.30 In the early 1970s, The Shoes of the Fisherman (Anderson, 1968), starring Anthony Quinn and Laurence Olivier, was banned, allegedly because the Chinese, who were then building the Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) railroad in Tanzania, objected to the film’s portrayal of their regime. But somehow, Shabir, the manager of the Empress, was able to convince the censors to allow the movie to be screened for a charity show. He recollected, “Once the film had been banned, but not for the charity show, people went crazy to get tickets. The normal price of a ticket was ten or fifteen shillings, but the black-marketeers were selling them for one thousand shillings instead. Can you imagine? This was the early 1970s, one thousand shillings was a lot of money! Our eyes bugged out of our heads.”31 The charity did well with its sold-out show, but the black marketers did better yet.

James Bond films were also huge hits with the audience—and maligned by the censors, who found them to be crass Cold War propaganda. From Russia with Love (Young, 1963) was banned on the mainland and in the isles in 1964, but it was later released as From 007 with Love after extensive pressure from exhibitors and James Bond fans caused the censors to relent. Black marketers also scored, for nothing boosted a film’s popularity with urban crowds like the censors’ wrath. The following year when Goldfinger (Hamilton, 1964) was released, all the tickets were sold within hours, but before the film was screened, the censorship board banned it. Dar es Salaam was in an uproar. For more than two weeks, letters to the editor in the national press were filled with scathing attacks on the censors, making letters complaining about the black market for tickets seem pale in comparison.32

Black marketers operated independent of cinema owners and managers, but they shared many elements of the capitalist ethos that permeated the industry at large. For one, they strove to be the best at what they did and competed—in a good-natured way—against others in the business for the right to be recognized for their success. They also helped each other out in a bind. If someone lost all his capital, others would chip in to help him get started again. If another hit the jackpot, he shared with his fellow black marketers and other friends to celebrate the success. “If one of us won big we would all shout, ‘Hey, today he is going to slaughter a goat and feed us all!’” said Khamis, and rather often the man actually did.33 If a man was ill and could not get to the theater on the day tickets went on sale, others bought up tickets for him. If police came around and tried to interfere with sales, they all pitched in to offer a sufficient bribe or a few tickets to make the police go away. And on the rare occasion when a man landed in jail for dealing in black market sales, the others pooled their resources to bail him out and make sure his case never made it to court. Just how many men earned their livings selling black market cinema tickets during the colonial era is unclear, but published estimates put the figure at twenty to thirty. By the 1970s, according to men in the trade, there were six or seven known dealers in Zanzibar and nearly fifty in Dar es Salaam.34