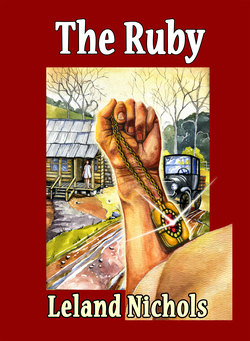

Читать книгу The Ruby - Leland Nichols - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER THREE The Accident

ОглавлениеAlthough it was late April, the early evening air was cool. On top of the decaying house, a chimney made from fieldstone spilled smoke, filling the air with the pleasant fragrance of a wood burning stove. As the truck continued up the lane toward the house, Dorian saw that the yard was mostly barren, naked of grass, and littered with ancient car parts and rusted farm implements. The farmhouse had deteriorated horribly over the years from neglect; the pointed roof sagged at the center and most of the wood shingles were more or less rotten. The house, as with most of the outbuildings and barn, was in need of repair or replacement. On the weathered and unpainted front porch, a woman in her mid-forties sat in a padded rocking chair holding a small child. She was Billie’s mother. Her head was in motion, her eyes following like searchlights as Billie, with her strange passenger, drove past. Four other children, stair-step in age, played in the dirt below the porch.

The truck continued across the yard alongside a barn with a weathered cupola. The remnants of several abandoned bird nests hung from the openings in the vent. Billie notched the throttle down, and the old Ford backfired like artillery fire, with a puff of smoke tumbling from the back. Finally, they came to a stop in front of a machine shed near the barn, in a patch of shade. The air was thick with the smell of oil, grease and dry rusted metal.

Billie stepped out of the truck, removed the blossom from her hair and placed it on the floorboard next to the gear shift. She held out her hand to Dorian. He took her rough, slender fingers in his hand, and side by side, they strolled toward the shed. Dorian scanned the area, a disappointed look on his face. Clearly, he had, in his naïveté, misjudged the situation badly.

“Your father’s not a geologist, is he?”

“I don’t think so, he jes’ farms,” she said.

They walked together toward a machine shed where a middle-aged man and two younger men were attempting to repair an overused, gas-powered tractor with iron wheels. Tactfully, Dorian withdrew his hand from hers as they approached.

“This here is Pa, and two of my brothers,” Billie said.

Dorian greeted them with a nod. He looked at Billie’s father, Clyde, as he crawled from under the tractor.

Clyde was in his mid forties and wore dirty, blue-denim bib overalls covered with spots of grease and oil. Sweat darkened the front of his shirt. A stain of dried tobacco juice was clearly visible in the whisker stubble on his chin. With brown nicotine stained fingers, he took off his hat and brushed the sweat from his eyes with the back of his sleeve. He was singularly tall and thin, not an overweight man by any means, the result of making a living through hard labor and strenuous toiling in the fields. He had worked this two-hundred-forty acre tract of land most of his life. It was a hard-working farming life, caught up in hard economic times. Long years ago, the railroad boom had brought its lines through the area because of the vast lumber mills and lead mines. However, the right of way through the property had been sold a few decades earlier before he had bought the land, unfortunately for Clyde’s family.

As Clyde lubricated a rusty section of bolts with an old long-nozzled, pump-handled oil can, he glanced over his shoulder at Dorian, looked away, then looked again in a quick double take. His gaze shifted to Billie as he wiped his palms on his thighs. Angrily, he said, “Billie, effen I’ve told ya once, I’ve told ya a thousand times, we don’t need any travelin’ salesmen ’round here.”

“His car broke down. He ain’t sellin’ nothin’.”

“You git on in the house and help yer ma.”

“But, Pa…”

“You heard me.”

Billie turned and walked toward the house. She glanced back over her shoulder at Dorian. Perhaps a last look before her father sent him away.

“We don’t take kindly to strangers snoopin’ ’round these parts. There ain’t nothin’ you need here, so be on yer way.”

Clyde was always troubled by the presence of strangers, and he did not trust them, mostly because of the moonshine still he operated in one of the hollows behind the house. He always suspected any stranger on his property, fearing that they might be Federal Revenue officials that could close down his operation and send him off to jail.

“I was hoping you could help me,” Dorian said.

Clyde ignored him and went on about his business.

“You see, I have a problem,” Dorian continued.

Clyde looked around on the ground, then at the shed, and said, “Sonny, fetch that long piece of pipe over there.”

Sonny was Clyde’s oldest son. At twenty years old, he was a rugged young man, stout as a bull with big arms and broad shoulders as wide as a door frame. Most of his size was sheer muscular mass. In his jaw, he had a large lump of tobacco that made quite a bulge on the side of his face. Sonny’s real name was also Clyde; being the first born son, he was given the name of his father. But he did not like being called “Junior”. Because of that, and so there would not be any mix-up when their name was brought up, they had decided to call him Sonny.

Sonny turned and picked up a large piece of pipe about eight feet long. His muscles bulged from his open shirt as he heaved the heavy pipe. He kept looking at Dorian, studying him from the ground up. There, in front of him, was a very strangely dressed person, like nothing he had ever seen before.

“Put it right dare, under the axle,” Clyde said. “Andy, git over here and help yer brother.”

Andy was sixteen, a tall, gentle-looking young man, meek and mild, somewhat childlike and shy. Slender-framed, he walked with a limp, and had only one useful arm. He carried the other arm clutched at his side; it was smaller and narrower, with limited movement, the hand locked in a ridged position pointing straight down. He was a cripple since the age of two and, unknown to himself or his family, a victim of polio.

Andy pulled a sliver of twig from his mouth and joined his brother and father beside the tractor. Sonny slid the piece of pipe under the rear axle to use as a pry bar. Clyde rolled a large stone under the tractor to use as a fulcrum, as Sonny positioned the pipe as a lever. Sonny and Andy pried one side of the tractor off the ground. Clyde crawled under the tractor, a wrench in his hand.

Dorian moved closer to Clyde, who was lying on his back tugging at a rusty bolt under the tractor. “I’m a stranger here, just passing through.” Dorian squatted down, looking at Clyde working away under the tractor. “If I could just take a few moments of your time?”

“I got my own problems. Fields to plow, no ’quipment to work with, and not enough time to do either.”

Sonny looked down at Dorian, becoming distracted by the unusual clothes the stranger was wearing. Suddenly, with the sound of rock crushing, then a dull metallic thud, the pry bar slipped. Sonny, unconsciously, put his hand on the rolling bar to steady it on the rock, pinching two fingers on his left hand that had become lodged under the bar. With a wince, he withdrew his hand and looked at the jagged wound. The flesh was torn, rather than being cut cleanly. The agony of pain registered on his face.

Clyde managed to roll out of the way barely in time, as the tractor slammed into the ground. He got to his feet, shooting Andy an angry look.

“Damn it, Andy, I told ya to help yer brother!” Clyde was always hard on the boy, not knowing, or not wanting, to accept his limitations.

He watched as Sonny backed away from the tractor, moaning with pain. Sonny slung his badly bruised hand up and down, and then cuddled it next to his body, clutching the torn finger tips. He gritted his teeth and doubled over in pain.

Clyde shouted furiously, “See now what ya done?”Clyde strode over to Andy, and in a fit of violent anger, slapped him open-handed across the face. Andy stumbled under the hard blow. He looked meekly at his father, blinking rapidly, his head almost touching his chest.

“Sorry, Pa.”

“Look here what ya done to Sonny.”

“I done all I could.”

“You could do a lot better, effen ya weren’t so damn lazy.”

His anger spent, Clyde stepped over to Sonny and put his hand on his shoulder. “Are ya hurt bad, son?”

“I’m alright, Pa, the pry bar got me. It weren’t Andy’s fault too much.”

“Get on in the house and warsh up,” Clyde said.

Sonny headed for the house as another of Clyde’s daughters approached them.

“Pa, supper is ready,” she said, tugging at the neckline of her thin summer dress.

“Alright, Amber, in a minute.”

Amber was eighteen, flower-like, with light-brown hair braided on both sides, fastened at the ends with strips of cloth. She was an overwhelming beauty, with a touch of wildness in her face. She made eye contact with Dorian and grinned mischievously at him, taking her bottom lip between her teeth, studying him.

Clyde turned to walk toward the house and noticed that Dorian had not left yet. In a somewhat exhausted manner, he looked Dorian in the eye and said, “Sorry, boy, I ain’t got time to help ya.”

Dorian turned to look at the lonely road, which seemed to lead to nowhere. He felt he had lost contact with the only people he knew, feeling cold and alone again. He glanced back at Amber again to find her green eyes still staring at him, a small smile parted her lips.

Amber perked up, her bright eyes set against a suntanned face, kept Dorian in their sight, “You can’t jes’ send him away without eatin’. Can’t he stay for supper?”

Clyde mumbled to himself, “Damn outsiders, comin’ ’round here tryin’ to git everything I own.” Then he cleared his throat and said, “Be on your way.”

“I won’t trouble you anymore,” Dorian said, as he turned and walked toward the road. “Thanks, anyway.”

Clyde took off his cap and raked a hand through his hair. He became tentative, as if having second thoughts as he watched Dorian leave.

“Car broke down, huh?” he called.

Dorian turned and faced him. “Not exactly.”

“Well, we ain’t got much, but you can come in and join us if ya like, before ya leave.”

Dorian smiled back at him, “Thank you. I’d be glad to join you.”

They started to walk across the yard, and Amber hurried to Dorian’s side, taking his hand as they went toward the house.

Billie and her mother prepared to serve supper as the family entered the kitchen. Billie wiped her hands on her apron as her mother opened the white enamel oven door of a black, wood-fired range with heavy chromed trim. She pulled out a cast-iron muffin pan of hot cornbread. Billie removed the stove lid, and a plume of carbonaceous smoke rose to the ceiling that tumbled and rolled to find the boundaries of the room.

Dorian came up to the kitchen’s screen door as Clyde’s nine children scrambled for a place at a large kitchen table bare of a tablecloth. Everyone except Dorian settled around the table, none of them taking the time to first wash their hands before the meal. Andy tried to get in a chair, but was bumped aside by a smaller child who took the seat. He limped across the floor to another place at the table. Amber was the last family member to come to the table. She had removed the braids from her hair, which now flowed loose half covering her cheeks. She smiled impishly at Dorian as she went through the kitchen.

Clyde looked across the room at Dorian, who was still standing in the doorway, the heel of one foot propped against the screen door, holding it partly open.

“Come on in, boy, have a seat. Yer let’n the flies in,” he said.

Somewhat hesitantly, Dorian walked around the table, taking a seat at the table in front of the cook stove. The straw-bottomed chair creaked as he sat down. The cast-iron range, still hot from cooking, gave off a metallic scent and radiated a gentle heat on the back of his neck.

Billie and Amber both scrambled to get into the chair next to Dorian. Amber got there first, and Billie tried to nudge her away.

Billie looked pleadingly at Clyde, “Pa, she’s in my chair. I always sit here.”

“No you don’t, Billie. You lie like a dog,” Amber said.

“Git up, Amber and let yer older sister sit there,” Clyde said.

“Ah, Pa. You always take up fer her.”

“Go on, git up.”

Pouting, Amber got up and walked around the table to take a seat right across from Dorian. Beaming, Billie sat next to Dorian. They began to pass bowls of food around the table. Ma carried a plate of fried meat to the table and set it down beside a plate of biscuits, well-packed with home-churned butter.

“Cooked up a mess of rabbit,” she said. “Andy went an’ shot it this morning.”

Clyde looked at Dorian and said, “Yer name’s Door’n, right?”

“No, Dorian,” he said quietly.

Clyde handed Dorian the plate of fried rabbit. “Here, boy, have some Hoover pork.” Clyde smiled briefly at this, chuckling to himself and said, “Well, Door’n, yer not from these parts, are ya?”

“As a matter of fact, I’ve traveled a long way.”

“Ya ain’t wanted by the law or nothin’ like that, are ya?”

“No. Nothing like that.”

“You don’t say much, do ya? Where ya from?”

“Actually, quite a ways from here. Uh… you’ve probably never heard of it.”

Clyde studied Dorian a moment. “A long ways, huh? What I’m tryin’ to figger out is, you travelin’ these dusty roads and ain’t got a speck of dirt on ya nowheres,” he said thoughtfully, stirring his coffee.

Dorian knew that a lot of explanations were due, but he considered it best to say nothing and continued to pick at his food, not knowing how to respond. After a few moments, he continued to eat.

There was no logical explanation, no way to answer. He remained silent, hoping the issue would end there. Clyde stared at him. He grinned as Dorian looked up.

“So, your car broke down. It still happens, but they make cars better than they used to. Years ago, when I was young, my father would drive all the way to town, but someone would have to go and pick ’im up. They’ll never be able to replace a horse, he used to say.”

Dorian smiled at Clyde’s remark and continued to eat. After a time, he looked up again, noting that Clyde was still studying him.

“Looks like you ain’t done a day’s work in all your life,” Clyde continued, and gave Dorian a quick wink.

“What makes you say that?” Dorian said, unsure what to make of the gesture.

“Them hands is jes’ like a young woman’s, and ya ain’t got no suntan, like ya never been outdoors. Wearin’ them fancy duds; ain’t no one ’round here dresses like that.”

“They’re just some old clothes I picked up.”

“Old?” Clyde said, as he laughed out loud. “I’d like to see yer good clothes.”

Amber and Billie both giggled.

“Maybe he’s a movie star, Pa?” said Amber. “He sure be handsome ’nough for one.”

“Quiet down, Amber,” said Ma, not raising her eyes from her plate. The younger children started to laugh, but stopped short as they saw the expressions of disapproval on Ma’s and Pa’s faces. Dorian squirmed in his seat, not pleased about being the center of attention. Finally, he decided to get to the point. “The truth is, I need a ruby. I can’t continue on until I get one.”

Clyde laughed out loud once again, and said, “Yeah, you and everyone else. Hell, boy, for most folks ’round here, that’s prob’ly two month’s work. I figger it’s ’bout time for another farmer’s holiday. We’ll eat our ham and eggs, corn and wheat, and let them big wigs in the city eat their gold.”

The grin left Clyde’s face as he noticed Sonny seated across the table, his hand wrapped with a rag, massaging it and not eating much.

“Izzat botherin’ ya?” Clyde said.

“It’s still sore, Pa.”

“Yer gonna be useless like Andy effen ya don’t take care of yerself.”

Andy, although embarrassed by the remark, managed to force a meek smile.

Dorian ate, feeling glad the attention had been drawn away from him. But it was only for a little while, as Clyde asked him, “What do city folks like yourself do in the evening after dark? You are city folks, ain’t ya?”

“I suppose you could say that. We don’t do much of anything, really. Usually, we sit and spend our time reading and studying.”

“Reading? Guess you all got that electricity and lights to read by. You don’t know what it’s like bein’ without electricity. Out here, folks don’t have time for readin’. When it’s dark, ya can’t do much, ’less ya go coon huntin’.”

Sonny turned to Dorian, “Ever been coon huntin’?”

“You mean, raccoon? Well I…no, I haven’t.”

“Nothin’ to it. You jes’ follow the dogs. Ol’ Buck’s the best coon dog there ever was,” Andy said.

“The best damn coon dog there ever will be,” Clyde said, putting down his coffee with a crack. “Ain’t ever been one like ’im and never will be. Why, he can track a coon through creek bottoms, across rocky cliffs. Ain’t gun shy either; fired a rifle next to his ear, didn’t even flinch. Trick to it is, ya have to know how to train ’em. Ya always let the dogs fight with the coon, after ya shoot ’im out of the tree. That way, the dogs get their reward in the hunt and it helps trainin’. ’Course ya have to call ’em off before they tear the hide up.”

“How ’bout it, Door’in? Ya wanna go with us?” Sonny said.

“I don’t think the time is right. Them coons have lost their winter fur and the hides won’t bring nothin’ this time of year,” Clyde said.

Well, Door’in’ ain’t ever been coon huntin before. Jes’ thought we might break him in on how it’s done. We could just go to run the dogs?” Sonny asked.

“I don’t want you to go just on account of my being here,” Dorian said.

“I reckon you best not pack any coons tonight anyway, Sonny,” Clyde said.

Andy perked up, “I can help ya, Pa.”

Clyde frowned back at Andy. “Ya slow me down, boy.”

Ma said, “You ain’t been gittin’ any coons, no how. Ain’t no sense in goin’ out again, this late in the spring.”

“Ol’ Bucks been a-treein’. Them coons jes’ outsmartin’ the other dogs somehow,” Sonny said.

“It’s dem persimmon trees,” Clyde said. “I figured out if a coon climbs a persimmon tree, he gets that scent on his feet, and the dogs can’t track ’im no more through the woods.”

Ma chuckled to herself and said, “Well ya don’t have to worry ’bout havin’ too many to carry.”

“No harm in tryin’, I guess, but Andy’s worthless when it comes to carryin’ anything,” Clyde said.

“Maybe Door’n can go with us and help carryin’?” Sonny said.

Clyde took a plug of chewing tobacco from his bibs, biting off a piece. He turned to Dorian. “You doin’ anything after dark?”

Billie was concerned about the late hours involved with the hunting trip. She said to her father imploringly, “You can’t expect him to go huntin’ with you, then send him on his way in the middle of the night.”

Clyde paused for a moment and said, “So, he can spend the night in the smokehouse. The roof leaks, but that ain’t no problem, ’less it rains.”

“Well, yes, I suppose I can go on the hunt. I don’t see any harm in doing that,” Dorian replied.

Dorian knew he must be constantly mindful of the Principal Mandate, of not interacting with people, but in this case he felt he had no choice. There was nothing he could do for the time being, until he found a ruby. He reasoned he could go along and hope these people will eventually be able to help him. Besides, going on a coon hunt at night with a bunch of hillbillies far removed from civilization didn’t seem to present any significant problem. The experience might even prove entertaining. At least for now, he had a temporary place to stay.

Everything has turned out quite well, considering the possibilities, he thought. He now felt that he could obtain another ruby soon enough, and then be on his way to continue his mission. But unknown to Dorian, the time-traveler, he was stranded in a place where finding a suitable ruby would prove to be quite difficult. What surrounded him were the hills of the Missouri Ozarks in the midst of the Great Depression.

Dorian grinned to himself. It looked as if his luck has changed... or had it? How could things possibly get worse?