Читать книгу The Ruby - Leland Nichols - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER FIVE A New Way of Life

ОглавлениеDorian was awakened at the crack of dawn by the sound of a freight train rumbling down the tracks, blowing its whistle. He swung his feet over the side of the bed, looking around the room. Unwillingly, he got up and started putting on the borrowed clothes, glancing out the window. The morning air was fresh and clean. Across the road in the valley, a dense mist hung in the air, a thin, translucent fog. A delightful morning, bright and fine, the eastern sky glowed pink, the red streak of dawn extending to the horizon. A rooster crowed from a fence in the barnyard.

He walked unsteadily to the washstand to wash his face. An old kerosene lamp with a cracked chimney, a chipped pitcher and a bowl had been placed there early in the morning while he slept, along with a razor and shaving mug. He thought that perhaps Billie or Amber had bought the things for him before they began their morning chores. He poured a glass of water from the pitcher and drank it down slowly. Putting water into the bowl, he bathed his face in the cool, refreshing liquid. There was the usual dawn chorus of the birds, as Dorian stepped from the smokehouse into the misty softness of the morning, still sleepy-eyed, to greet the sunrise.

Dorian strolled down toward the barn where he saw Clyde and Andy working on the tractor again. Clyde looked up as Dorian passed by. “Ya missed breakfast. Didn’t know if you’d already left or jes’ overslept.”

Dorian raised a hand in greeting and continued toward the barn, the huge double doors swung wide open. At the doorway, he met two small children struggling with a large bucket filled with foaming white milk, the frothy bubbles giving off a warm fragrance. Dorian was hungry and the smell of the fresh milk whetted his appetite. As they passed him, he admired the bubbly foam floating on top, whipped to froth.

The strong smell of dry hay and decaying grain filled the air as he entered the barn. There were several small children in the barn trying to help out the family in any way they could. A small boy just starting to walk laboriously shuffled toward him, encumbered by a large barn cat. The youngster put the cat down beside Dorian and stood with a self-satisfied smile, feeling proud for having brought the animal to him. Dorian knelt on one knee, picked up the cat, laid it across his lap and stroked its fur. He could tell the cat had seldom been shown any affection or handled in such a fashion.

Inside the barn, Billie was seated on a three-legged stool milking a cow. Dorian walked over beside her and sat on the ground, watching and listening to the rhythmic pinging of milk squirting into the bucket.

“Did ya like goin’ coon huntin’ last night?” Billie asked with a glance in his direction.

“To be honest, I wouldn’t care if I ever went again.”

“You probably won’t. Coon hides don’t bring much in the spring, after they lose their winter fur.”

“He sells the hides?”

“A winter fur is ’bout five dollars, but them spring hides are lucky to bring three. He takes ’em on into town once they’re cured. But Pa says they’re ’bout hunted out.”

Outside, the chatter of the Model T engine was heard as the old automobile rumbled up.

“What the hell took so long? ‘Bout time you got back,” Clyde yelled.

Billie and Dorian peeked out the side of the barn to look. They saw Sonny get out of the truck, retrieving a horse collar from the pickup bed. He had his injured hand wrapped in an old dishtowel.

“How long does it take to drive over to the Sullivan place?” Clyde said, tapping his thigh with a fist.

“You said ta take it easy with the truck, Pa.”

“It ain’t but half a mile. You been gone nearly two hours.”

“Well, Greta got to talkin’. She wants us to come over tomorrow evenin’. A barn dance or something.”

“Good, it’ll give me a chance to peddle some ‘shine,” Clyde said.

Billie sat back down and started milking again. “Effen ya help Pa with the chores, he might let ya stay a few days.”

“I’m afraid I won’t be of much help. I don’t know anything about farming, aside from what I’ve read.”

“You learn quick, I can tell,” she said with a spreading grin.

Billie heard Clyde yelling at her outside. “Billie, ain’t you done milkin’ yet?”

“Just a minute, Pa,” Billie yelled back. She picked up the bucket of milk and turned to Dorian. “Pa says the tractor needs a new axle. Can ya help ’im?”

“I know something about machines in general, but not much about tractors, but I’ll do what I can.”

An impatient Clyde yelled again from outside, his voice more angry. “Billie, git out here!”

Billie sat the bucket down and took Dorian’s hand, pulling him into a stall, out of sight. She stood on her toes to look around to see if anyone is watching, just in case, then surprised Dorian with a quick kiss on the lips. Dorian was shot with a flood of emotions, among those, embarrassment. Stooping, she picked up the milk, “I have to go,” she said, hurrying out the door, leaving Dorian red-faced.

She walked past Clyde and Sonny without stopping and said, “Dorian is going to stay a few days to help us out.”

“Good. We can use extra hands while Sonny mends up,” Clyde said.

Later that evening, Clyde got up from the supper table, going into the living room to sit in his easy chair. The evening air was cool, and the warmth of the pot-belly stove was quite relaxing. It was not a roaring fire, only a few hot coals simmered, just enough to break the chill. He sat in the armchair, his sad eyes exhausted from a hard day’s labor in the fields. Two small children joined him, sitting on the wood-box near the stove. Dorian entered the room holding Billie’s hand. Ma handed Dorian a bundle of clean clothes to put on for the dance tomorrow night. Thanking her, and whispering a good night to Billie, he took the clothes and left the house through the back door.

Clyde slumped into the arm-chair, pulling a linen bag of tobacco from his bibs. He reached for his pipe on the table next to his chair, filling the bowl with the tobacco, lighting it with a match. He pulled the yellow string on the tobacco sack with his teeth.

Dorian had done well enough that day, he thought. He was stronger than he looked and eager to work. Clyde had even enjoyed his company at times too, partly because Dorian’s callowness gave him some easy amusement.

The next evening, Clyde loaded the kids into the truck, and Billie hitched up a horse to the old buggy. Ma got in the truck, after setting a wooden box of canned goods in the back. There were wide-mouthed jars of vegetables that she and Billie had canned last summer: green beans cooked with potatoes and stewed with bacon stripes, and some smaller jars of tomatoes.

The trip to the Sullivan place was only a half-mile down the road. A few minutes later, as the sun went out of sight below the far hillside, they turned off the road and followed a beaten path through the pasture to the barn behind the Sullivan house. There were a few automobiles and several buggies parked haphazardly in an open field along with riding horses beside a well-lit barn. The horses, some hitched to buggies, stamped and swished their tails at flies in the shade. From a distance, the evening songs of the bobwhite and the whippoorwill were almost drowned out by the sound of music and joyful exuberance and merriment radiating from the barn.

Along with the family, Dorian walked toward the barn where he saw several young fellows at the entrance talking to some girls. Occasionally, one would take a nip from a pint-size mason jar, then pass the jar to the next. All of them appeared to be under the influence of drink. Some teenage boys had cooked a pig in the ground, so there was plenty of meat. Just outside the entrance of the barn was a row of tables filled with home-baked bread, mounds of mashed potatoes and green vegetables. There were lots of desserts: cakes, cookies with hickory nuts, and apple pies reeking of cinnamon. There were not enough tables, so some planks had to be set up on sawhorses to provide improvised accommodations.

Unlike the bread lines and soup kitchens of the big cities, here country folk usually did not suffer overly much from hunger, as long as the harvest was good. They had little to lose before the depression; they, like so many others, were already broke when the banks failed.

The sound of laughter filled the air along with fiddle and guitar music. Here were people who did not like living near anyone but enjoyed each other’s company at a barn dance with a good fiddler and a traditional square-dance caller. People came from miles around. Most of the boys were eager to meet girls. Most of the young ladies would show up at this sort of gathering to collect a husband. A young man and woman sometimes left the barn together, trying to be discreet as they stole a few private moments together.

Inside the barn, the band was set up on a platform, and the people were dancing on the dirt floor in the center section of the outbuilding. Greta Sullivan danced with her husband, Raymond, both in their mid-thirties, the hosts of the party. Sonny went to cut in and dance with Greta. Off to one side, Andy sat alone on a hay bale watching, chewing on a cookie, his foot tapping nicely to the fiddle. His handicap limited other activity.

Dorian tried to keep himself hidden, standing deep along the sideline among a group of people in the back, away from most of the action. It made him appear a shy person, as indeed he was. In his own time though, he would have been a little more sociable. His eyes swept across the room at the faces, the joy and laughter of people having a good time. He was amazed by them; here was a group of people who had almost nothing, and were experiencing the worst of times, not knowing if they would have something to eat in the coming months or what terrible misfortune would strike next, yet they still have it within them to enjoy the fine things in life.

Amber danced with a local boy, but her eye was frequently on Dorian, glancing at him often to see if he was watching her. The band picked up the pace with the fiddles, and, all around, the tapping of boot-heels unsettled a little more dust. Billie left her dance partner and worked her way amidst the crowd toward Dorian.

“Aren’t you goin’ to ask me to dance?” she asked Dorian, pouting.

Dorian looked again at the people dancing and having a good time.

“I shouldn’t even be here,” he said, shaking his head, his hands fidgeting.

“That doesn’t matter, silly. You’re here and that’s that. Come with me.” She started to take Dorian’s hand but was yanked away to the dance floor by another young man. Dorian retreated outside into the cool night air.

Several men sat around a small fire drinking and laughing out loud. Money exchanged hands as Clyde passed pint-size mason jars containing moonshine whiskey to another man. Although not a large moonshine operation, his product was known locally for its quality. He used a copper radiator as a still. The old radiator was sunk in a cold creek, fed by clear springs to distill alcohol vapors, heated over a wood fire into a large copper vat. Clyde did not take the time to age the alcohol for five or ten years in charred oak barrels so as to enhance the favor. Instead, he used his own sour-mash method: adding a batch of fermented mash from a previous batch, like making sourdough bread. He did not consider himself a bootlegger as such but as providing a service folks nearby could not get elsewhere.

Clyde leaned back on a wooden box containing several fruit jars of his home-made brew. He noticed Dorian standing near the doorway, staring silently into the fire, spellbound by the flames.

“Hey, boy. Take a load off your mind,” Clyde called. “Come ‘ere and have a drink.”

“What is it?” Dorian asked, as he walked over to Clyde and sat down beside him.

“Don’t be worrin’ ’bout them revenue men. Hell, I sell it to them, too,” Clyde said, offering Dorian a jar and pulling a Bull Durham tobacco sack from the watch pocket of his bib overalls.

Dorian took the jar, and removed the lid. He took a sniff from the open container and looked up at Clyde with a grin, “Is this what’s referred to in history as ‘white lightning’?” Dorian bit his lip and winced over that slip of the tongue.

Clyde smiled and said with pride, “Corn liquor, my boy. My own homebrew. I make it down by the creek. Spring water, and a little flavorin’ from the peach tree.”

Dorian put the liquid to his lips. It burned, and his eyes watered instantly as he took a swig from the jar. His mouth opened wide as he exhaled a long breath to cool the burning sensation on his lips and mouth.

“Oh, my!” he said. “Almost pure ethyl alcohol.”

Clyde and the other men around the fire had a good laugh.

Clyde held up his cup as if to make a toast, “Yep, pure history. The county judge calls it, ‘illicit untaxed whiskey.’ This ’ere home brew can sneak up on ya fast, hit ya like white lightnin’.”

Dorian forced a smile, but suddenly turned away from the glare of the fire on his face. He didn’t want the others to see the worry on his face. He stared across the open meadow to the wood line, the flickering light, the dance of shadows. Amongst all the noise and laughter, a sudden fear crawled over him; anxiety and terror started to take a grip on him. He stood quickly, walking away a few paces to consider matters.

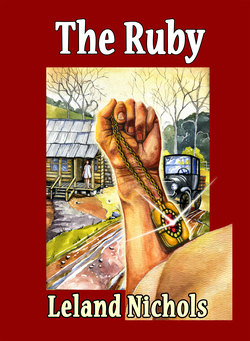

This is taking too long, he thought. No progress had been made in obtaining a ruby, and there was not as yet any real hope in finding one. It was his goal during his time-travels to gather from the collective wisdom of the generations, to gain insights into what was right or lasting, and learn how to handle every situation. He worried about how he was violating the Principal Mandate—just observe and don’t get involved. That was the fundamental point that the planners of this mission emphasized; follow that and you cannot get into trouble. But what should one do in this situation? The possibility of a major break down of a time-portation device’s ruby component had been overlooked by the scientists at the Quantum Institute.

Dorian’s main concern was the causality effect—whether an effect can occur before it is caused. The classic example is the Grandfather Paradox; what would happen if a time-traveler went into the past and was responsible for his Grandfather’s death, before his ancestor had had children? Other paradoxes could manifest, as well. Yet what else could he do? Under these circumstances, avoiding contact with people was not possible. He clung to the hope that whatever change he was making to the fabric of time was negligible.

Dorian looked at the men gathered around the fire in all their gayety and joy. To them, he was a stranger, but it did not matter to them at all. It seemed, at times, the easiest way would be just to tell them he had traveled here from two thousand years in the future and was in desperate need of a ruby. He could always tell the entire story at some later time, in the hope that it would not be too far off. In the meantime, he thought, he would try and make the most of the opportunity.

The next morning, Dorian made an effort to get up at least in time for breakfast. His daily routine began at six o’clock every morning. Each day started out just like the day before, and tomorrow would end the same way as yesterday. First there was milking, then tending to the animals, fixing anything that needed fixing, plowing and planting the fields, then milking again in the evening. Most people in that era and region milked their own cows or depended upon farmer-peddlers to supply them with raw milk, none of which was pasteurized.

At times Dorian and Billie worked side by side. Thinking she could do with some cultural improvement, he made an effort to supplement her poor education. During his conversations with her he was continually correcting her grammar and pronunciation of words, something that irritated her at first, but gradually over time she accepted it with a smile. She was taking delight in having more mannered speech, asking him over and over whether she sounded like a “fine lady” yet.

Andy’s job was mostly to feed the chickens and gather eggs. He also fed and watered the dogs. His handicap prevented him from doing most of the more laborious tasks. Sonny had done most of the hard work that involved heavy lifting and other strenuous tasks, but now, with the injury to his hand and arm that would change, at least during the course of the next few days.

That same morning, Andy was on the front porch making butter in a churn. Normally it took half an hour of cranking the churn to make butter out of cream, but with Andy it took a little longer. He had been out earlier that morning looking for morels and any other edible mushrooms he could find. Amber was in the living room mending some of the younger children’s clothes with a foot pedal-powered sewing machine. Ma was washing a large crock and other dishes at the sink. Billie was also in the kitchen, giving haircuts to the younger boys with a pair of hand clippers and scissors. She had them draped with a linen cloth and seated in a highchair. The boys were uncooperative and impatient during the session. Often they were brought to tears, complaining that the clippers pulled their hair and the sharp bristles of their cut hair stung the back of their necks. It was that sort of prickly irritation that needed to be scratched.

“You found out anymore ’bout that man?” Ma asked.

“What man?”

“You know who I’m talkin’ ’bout.”

“Oh, you mean Dorian? He doesn’t talk much.”

“You and Amber jes’ keep yer distance, ya hear? Stay away from him.”

“I will, Ma,” Billie said.