Читать книгу The Ruby - Leland Nichols - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER FOUR The Hunt

ОглавлениеAmber ratcheted the hand pump, drawing water into a pan to put it on the stove. The cast iron pump with its wide spout was the nearest thing to running water in the kitchen. The well was directly under the porous stone sink where Billie and Amber stood washing dishes. The well was fed from the roof by a network of steel gutters that circled the back porch, with a trough angled down to direct the channeled rainwater. Most farm homes of the period had a well outside, and the water had to be drawn up with a rope and bucket to be carried inside.

Ma put away some of the pots and pans, then went to the kitchen table to gather up the rest of the dishes. A large, strong woman, but not obese, she had grown up knowing all the country ways of canning foods and tending to livestock. She knew all the things that kept a homestead running smoothly, within the limits of what little they had on hand. She emptied some freshly churned buttermilk from a big, brown churn and set it down nearby for Billie and Amber to wash.

The air smelled of woodsmoke from the kitchen fire, the warmth quite pleasing in the cool evening air. Dorian got up from the table and walked to the sink beside the girls. “Can I give you a hand with that?”

“Nah. Them girls can do it,” Ma said.

Clyde pushed back his chair and rose from the table, slowly standing upright, hooking his thumbs at the sides of his bib overalls. Ma began cleaning the supper table, as Clyde headed off toward the living room.

Dorian reached for a long handled cup hanging on the wall, putting the dipper into a bucket for a drink of water. He left the kitchen, wandering into the living room through a maze of clutter. The house was clean enough, though somewhat untidy. Clothes were stacked on the floor from lack of closet space, and wooden boxes were scattered about the room with blankets piled on them. A wooden Atlas dynamite box served as a footrest in front of an old easy chair, next to a pot belly stove. Dorian scooted sideways, scanning from ceiling to floor. The plaster walls were quite uneven he noticed as he bumped into a barrel-topped trunk. Propped up against the wall next to a stone chimney was a small caliber rifle. Next to it, a gallon earthenware jug of moonshine, with a corncob stuffed in the opening as a stopper. To supplement the family income, Clyde had been in the moonshine business for several years. It was distributed to some with ailments, though more often to those who enjoyed its consumption.

Clyde edged into a corner pushing the Atlas box aside with his foot and settled down a bit slowly in the easy chair beside the pot belly stove. He reached across to the wood rack and slivered a toothpick from a piece of kindling. Putting some tobacco in his pipe, he laid back in his chair. Clyde took a long puff on the pipe and let the smoke drift out slowly. It was his custom after a meal to sit alone in his favorite chair, not wanting to be disturbed by anyone.

Dorian walked out through the screen door into the night air of the front porch. Amber heard the door slam, and said to her mother, “Ain’t ever heard of a man wantin’ to help out in the kitchen.”

“Yeah, and we don’t know who he is or where he came from. Remember that,” Ma said.

“You can tell he’s from the city.”

“You jes’ watch yerself ’round him, ya here?”

“Seems like a nice ’nough man.”

Ma threw her dishtowel down on the counter. She shook her finger at Amber. “He’s still a stranger, and ya can’t trust him. Don’t take your eyes off him for a minute while he’s nearby.”

Ma noticed that Amber had removed the braids and the rags that secured her hair. Now brushed straight, it shined delicately in the dim light, giving her the appearance of a more mature woman, instead of a young girl. Ma lifted the hair off Amber’s shoulder, letting it flow across her hand.

“Yes, don’t take your eyes off him for a minute. Shouldn’t be hard for you to do.”

Clyde called out from the living room, “Billie, come in ’ere a minute.”

Billie put down a dishtowel, wiping her hands on her apron, as she walked to the next room.

“Yes, Pa.”

“You met up with Door’n down by the river?”

“I did. Don’t know where he come from.”

“I thought first he might be runnin’ from the law.” Clyde paused for a moment to think. “That’s it,” he said, snapping his fingers. “He must’ve robbed the bank in Springfield. We find out where he hid that loot and take it from him. Billie, did ya look in his car?”

“He ain’t got no car.”

“That’s what he said, huh?”

“Well, I didn’t see one, no wheres.”

“The get-away car, he’s done pushed it in the river. That means he hid the money down by the river.”

“Oh, Pa, he ain’t no bank robber.” She turned and walked back to the kitchen, a sheepish grin on her face.

“Well, how do you suppose he got here, effen ya didn’t see no car?” Clyde said, jabbing the air with a finger.

Dorian sat on the front porch, listening to the chirps of summer insects, his feet dangling off the edge. He stared up at the night sky, gazing wondrously at the stars watching the full moon go in and out of the clouds near the horizon.

Billie appeared at the front door. She swung the screen door open and stood in the entrance, her body silhouetted by the light behind her. She walked across the porch and stood beside Dorian, an arm wrapped around one of the support posts that flanked the steps.

“You like lookin’ at the stars?” she asked.

Dorian sighed with pleasure. Even with the full moon rising, the stars in this countryside were brighter, more vivid than he had ever seen before.

“There sure is a mess of stars out there,” Billie said, gazing upward too. “A penny for yer thoughts.”

“Oh, just some speculation about symmetry in our world. You see that bright star there, just above the horizon, it’s actually not a star; it’s the planet Venus. I was just thinking about how the objects in the sky are of the same apparent sizes from our vantage point here on earth. The sun and the moon are almost exactly the same apparent size, and all the stars and planets look like pinpricks of light, even though they differ in size greatly. They are placed at the right distances so as to make them appear the same size. And what’s most amazing is that many of those stars that don’t look so bright are incredibly far away. Others aren’t stars at all; they’re gigantic gaseous clouds of luminescent vapors—one of those is part of Orion’s sword. In some cases though, they are very, very faint; some “stars” are actually globular clusters of hundreds of thousands of stars.”

“How do you know about things like that? To me it had never mattered much,” she said. She knew there was something special about him from the first moment she set eyes on him.

“The boys are gettin’ the dogs ready. You can wear some of Sonny’s clothes, if ya like,” she said.

“That’ll be fine,” he said, still looking up at the stars.

Billie slipped over and sat down beside Dorian, her bare feet draped by a pool of moonlight. “Smell the night air. Isn’t it so fresh?”

Dorian was mystified by the wonders of the nightlife that began to stir the silence around him. The wild cry of a coyote on a far hill was answered by another from the valley. Then a nighthawk screamed during its flight across a nearby meadow. The sounds of the Ozark night, mysterious and sublime, were something beyond his range of experience.

Dorian finally glanced over at Billie. She had combed her hair, washed her face and put on a clean dress, clothesline-dried and wrinkled. The dress was plain and worn but probably the best she had, he thought. Dorian looked her directly in the face and smiled. She was even lovelier that evening than she had been when they first met near the stream. A gentle breeze floated across the porch, rustling her hair. The moonlight, filtering through the leaves and branches of the trees, illuminated her face, casting shadows that danced across it.

Dorian took a deep breath of the night air and slowly exhaled. He paused for a moment, then asked, “Why do they call you ‘Billie’?”

“It’s ’cause Pa was hopin’ for a boy, ’cept it ain’t spelt the same way.”

His gaze traveled from her eyes to her shoulders and down to her waist. “I see.”

She slid closer to Dorian. “I’m glad Pa let ya stay. Must have takin’ a-likin’ to you. He’s not like that.”

Dorian sighed. “I wasn’t prepared for any delays. But what else can I do; I’m stuck here.”

“Are you late?”

“That’s the best part; time is on my side. I’m never late.”

They smiled at each other. She leaned toward him, pressing her cheek against his. He reacted strangely to her touch, withdrawing a few inches from her and said, “Can I ask you to do something for me?”

“Sure. Ask whatever you like.”

“You promise you won’t laugh?”

“I promise, I won’t. Tell me.”

She moved her head closer to his again, her eyelashes fluttering against his cheek.

“That’s not what I had in mind,” Dorian said. “What I wanted to know…uh…could you tell me the date?”

She backed away, slapping him playfully on the shoulder. “Is that all you wanted?”

“Yes. You see, I have no idea. I’ve been through some confusing experiences lately.”

“It’s Friday, silly.”

“Friday, huh.”

She smiled, nodding her head.

“What year?”

She laughed hysterically.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“Shucks, most folks forget what day it is,” she said.

“You promised you wouldn’t laugh,” he said, laughing too. Her laugh was wonderful, infectious.

She stopped laughing and studied him a moment. Then the grin on her face faded away.

“You’re really serious, ain’t ya?” she said, her head tilted to one side.

“Yes, I am. I’ve lost all track of time.”

“It’s 1932.”

“You’re sure it’s 1932?”

“Pretty sure. Yes.”

“My God, they were way off. I expected some degree of error, but not this.”

“What are you talkin’ about?”

Billie’s mother appeared at the screen door and said, “You best get dressed, boy. Here’s some clothes for ya. Sonny’s a bit bigger than you, but there’s some suspenders to keep your britches up.”

Billie jumped up, went to the door and took the clothes to Dorian. “The smokehouse is ’round back,” she told him, pointing in the general direction. As she turned to go back into the house, she looked back at Dorian, staring at him in bewilderment as he tucked the bundle of clothes under his arm and headed toward the smokehouse.

Following a pathway, he could see the outline of the smokehouse off in the distance. Faintly, he heard Clyde and the two boys down at the barn making preparations for the big hunt, their voices drowned out by the sound of barking dogs.

Dorian reached the smokehouse and opened the door. He stepped inside, panning the room quickly. There was no lamp anywhere in sight. A candle stub next to a large box of kitchen matches stood in a saucer on a small table by the door. He lit the candle, then looked about the room at the new surroundings, cobwebby and decrepit. It was a run-down dwelling, small and rather untidy, no longer used as a smokehouse. Dorian had learned at the supper table that the building was once sleeping quarters for Amber, Billie, and two of the smaller girls. A few years back, Clyde and Sonny had added two dormers and windows to the attic of the family house, making two extra rooms there. A covered breezeway separated the main part of the house where Billie and her younger siblings slept.

Dorian continued to explore the little dwelling. Below was a dusty wood-plank floor, above a water-stained low ceiling, spotted with black mildew. A battered wicker chair, a dresser, and a bed were the only furnishings. Patterned wallpaper was peeling from the walls layer by layer, exposing the dry, porous plaster beneath. Dust had accumulated on all surfaces. A single window faced the front, covered with lace curtains stained by moisture and bleached by the sun, showing years of neglect. He examined the bed, pushing the mattress with the palms of his hands, testing it for firmness. It seemed comfortable enough; a wrought-iron bed with chipped white paint, high steel springs with a mattress covered in quilts, home-made from worn-out garments, sewn into patches. On the floor below the bed lay a hand-braided rug.

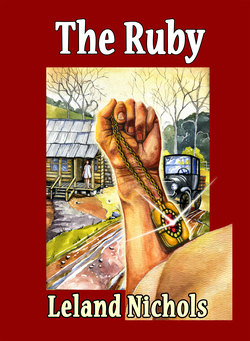

Dorian unzipped his silvery-white one-piece suit to change into the less conspicuous country clothes. He took the gold medallion-looking device from the pocket of the coveralls. It was oval-shaped, about three by four inches long, attached to a long chain. It was the time-portation device that no longer functioned properly. He stroked the red ruby located at the center of the device gently with a thumb. The ruby, the failed component, had left him stranded here. In his mind it was only a temporary setback, and somehow he would find a replacement ruby and continue on his mission. He pressed different indentations around the outside edges of the device; the ruby began to glow with a faint red light. Though it was not functioning properly, he dreaded the thought of leaving it out of his sight, and was reluctant to remove it from his person. He knew, however, that he had to in this case. The device was delicate, and if it somehow became lost or damaged in the dark woods, he would be lost forever in this time period. He folded the protective coveralls, putting them in the chest-of-drawers at the foot of the bed. Even though the device was not working at the moment, it gave him comfort to know it would be safe. He deactivated it and put it into an old cigar box, placing the box with its precious cargo in the top drawer of the dresser.

Adjusting the suspenders holding up his pants, Dorian stepped outside the smokehouse. Off in the distance, he saw the yellow, flickering light of a kerosene lamp glowing inside a tatty lean-to, a sloping roof off the side of the barn with no walls. Clyde, Sonny and Andy were under it making final preparations for the hunt. Three coon hounds danced around impatiently, knowing the hunt was on.

Good dogs were very important for a successful hunt. They were a prize for the folks that lived in the back woods and hills of the Ozarks. Clyde and Sonny were proud of the dog they raised from a pup. They had named him Buck and trained him only to run coons at night. The lack of success on a night of coon hunting with Buck on the trails was blamed on the increasing rareness of the game.

The coon hides could be sold for five dollars each in the city, a tidy sum of money in those days. In other words, a good coon hide was equivalent to a week’s pay and hard work at the lumber mill, which was the best paying job in the area. A successful two or three hour hunt in one night could bring in a month’s wages. The peak fur season was during the colder months of the year (November to February) when the animals had their thick winter fur.

Sonny unchained one of the dogs from the barn post, while Clyde prepared other gear for the hunt. A few feet way, Andy untied Buck, the black ’n tan coon dog they had talked about at the supper table. Andy felt a cold nose press against his out flung hand. He patted him on the back playfully, then knelt down, rubbing the dog’s fur and long ears. “Good boy, Buck,” he said to the dog.

Clyde looked over with disgust. “Don’t be ’fectionate with them dogs. How many times I gotta tell ya, he ain’t no pet.” Andy backed away from the dog, rubbing at his pants leg. Nothing he did seemed to be right.

Clyde turned his cap backward and strapped a carbide lamp, the kind coal-miners use, around his head, adjusting the lens. He turned to Sonny. “Ya got yer knife sharpened? We’re gonna have some coons to skin directly.”

Andy stayed behind, watching the trio leave for the woods behind the house.

Dorian, Sonny, and Clyde left the clearing of the meadow and stepped into the dark under-brush of the vast forest. Sonny had Buck on a leash, and Dorian was pulled along by another dog. They stopped near the bank of a shallow creek lined with willows and cottonwoods.

Clyde held out a lantern to see a wider area. “Looks like a good spot to turn ’em loose,” he said.

Dorian and Sonny unleashed the dogs, and in the yellow hue of the lantern, the dogs began circling and sniffing the ground. Buck was standing with his right front paw raised, sniffing and whining, his long ears fanned open. Then, along with the other dogs, he darted into the blackness of the woods, disappearing in the thick timber.

Stretching his arms, Clyde sat down on the trunk of a fallen tree. Dorian looked at Clyde then at the area of the woods the dogs disappeared into and asked, “Aren’t we going to follow them?”

Clyde laughed quietly and said, “You can, effen ya think you can keep up. As for me, I’m gonna sit a-spell under this ol’ sycamore tree.”

“How do you know when they’ve found a raccoon?”

“They’ll tell ya,” Clyde said matter-of-factly.

Sonny laughed as he knelt to a squatting position. “The dogs don’t bark, ’cept when they’re on a scent.”

Clyde pulled a plug of tobacco from his bib overalls, extending his hand to offer it to Dorian. Dorian shook his head. Sonny sat down in a cushion of grass and drew his knees up to his chest with his left arm. He had snapped off a twig from a wild grapevine about the length and diameter of a cigarette and was smoking it. The grapevine was not green but dry and porous. A substitute for tobacco, it burned the tongue but was otherwise a delightful smoke.

The silence was broken with the sound of a dog barking in the distance. Clyde did not seem too excited at that moment. “That dog’s separated from Buck, prob’ly chasin’ a bobcat again.”

A minute or two later came the sound of a dog barking from another section of the woods.

Sonny stood from his crouched position. “Y’hear that? Ol’ Buck’s on to somethin’.”

Clyde turned an ear to listen. “They’re over by the green swamp. Them dogs is runnin’ in circles.”

“No, they ain’t. Not Buck,” Sonny replied.

“An old coon can fool a dog by walkin’ the rail fence,” Clyde said knowingly.

Soon, the barking in the distance became more aggressive. Clyde became excited, and he jumped to his feet, turning an ear to the far off yapping of the dogs. “Come on! Ol’ Buck’s got one treed.”

Dorian, Clyde and Sonny ran through stands of wild cane, then waded through a shallow creek, coming to a group of trees where the dogs were howling and sniffing the ground. The stream was ankle-deep, but a large slough had formed at the bend of the creek, making a waist-deep wash. Buck was on his hind legs, his front paws extended up a tree, signaling this as the tree the raccoon was in. Clyde turned on the carbide lamp strapped to his head, aiming the light high into the tree. The beam flickered along the tree limbs then, finally, onto a raccoon, perched in a fork of the branches. The raccoon looked down at them. Blinded by the light, its eyes shone like headlights, making it an easy target. Clyde shouldered the rifle, taking aim. A shot rang through the quiet forest.

“I think ya got ’im, Pa,” Sonny called.

The raccoon descended half way down the tree and then leapt to the ground. The dogs attacked, growling and snarling, as fur and dust engulfed the air around them. After a brief scuffle, the raccoon managed to break free from the dogs, running to the creek. The dogs gave chase, splashing through water, paddling toward it. Buck caught up to the raccoon and sank his teeth into the animal’s hide. The raccoon rolled in the water and broke free of Buck’s jaws, climbing onto the dog’s head.

Clyde ran to the edge of a wide gravel bar covered with a foot of water and yelled, “Damn it, Sonny, git them dogs outta there!”

Sonny plunged into the knee-deep water and waded to the dogs. Buck struggled under the weight of the raccoon on his head. At times, Buck’s head was submerged out of sight. Clyde became frantic, yelling from the creek bank to Sonny, “Git a-hold of ’im. That coon’s gonna drown that dog.”

Sonny stumbled through the water, finally reaching the dog’s neck, pulling his head out of the water. Dorian grabbed a branch and quickly waded through the water to help Sonny. Sonny extended his hand to push the raccoon away, but their prey jumped up on Sonny’s back. He fell to his knees, reaching back to grab the raccoon’s fur behind its neck to pull it off. The raccoon hugged Sonny’s arm tenaciously, biting him several times along the forearm. Dorian raised the branch, trying to find a moment to strike the animal. With a howl, Sonny slung his hand, and the raccoon was flung loose, landing in the water. As Sonny grabbed Buck, the raccoon crossed the creek, scampered up the creek bank and vanished into the foliage. The other dog chased after the raccoon, disappearing in the blackness of the night.

Steadied by Dorian, Sonny lumbered out of the water, holding Buck by the collar. Clyde was waiting at the creek bank.

He looked at Sonny’s bloody arm. “The sum-bitch got ya, didn’t he? Least we got the dogs out.” Clyde removed his jacket, spreading it out on the ground. The three trekked back through the woods to the house.

Clyde had left the jacket on the ground so the dogs could come back to it during the night. Usually the next morning, the dogs would be laying on it, waiting for someone to pick them up.

Back at the house, Clyde helped Sonny as they entered the back door. Sonny sat down at the table as Ma and Billie entered the room dressed in their nightclothes. With gasps, they saw Sonny’s torn sleeve and bloody arm, realizing the tragedy was the result of being badly mauled by some animal.

“Son, what happened?” said Ma, aghast.

“Damn coon gnawed on his arm,” Clyde said.

After a moment of staring in stunned silence, Clyde yelled, “Damn it, Billie, don’t jes’ stand there, git some water and clean ’im up!”

Clyde left the kitchen for the living room, leaning the single-shot rifle against the corner of the fireplace. He began rummaging in a closet searching for a box.

Billie took a hand towel, folded it to a flat pad and held it under the cool, running well water of the pump. She went to Sonny, her hands trembling, as she held the wet cloth against the wounds, pressing gently. Then, with a circular motion, she wiped the area of the injury. She took a linen cloth, biting an edge, preparing to tear it into strips.

Clyde returned with a mason jar containing some of his one hundred-eighty proof moonshine alcohol. He poured some into his open palm, then splashed a generous amount on Sonny’s forearm. With a flinch, Sonny moaned.

Dorian retired to the smokehouse. He opened the top drawer of the chest, took out the cigar box and placed it on top of the dresser. Opening the box, he looked inside, just to reassure himself that the time-portation device was still where he had left it. He lifted the device from the box, holding it by the chain. It swung like a pendulum for a moment as Dorian stared at it.

Outside, Amber wandered along the path to the smokehouse. She stopped at the window, peeking inside. Her eyebrows raised, she saw Dorian looking at the strange object, which she took be a beautiful necklace. The gold glinted in the faint candlelight, and the large ruby shown like a red star. She had seen nothing finer. And, although she assumed it was mere necklace, she was moved by its beauty.

With a small sigh, Dorian put the device back into the cigar box. Suddenly he felt very tired. He unbuttoned his shirt and sat on the bed to remove his shoes. There was a soft knock at the door. Blinking, he opened it to see Amber. Abruptly he closed the door on her, racing to put the cigar box away into the top drawer. Amber opened the door herself, entering the room slowly. Dorian was quite surprised to see her.

“Amber, what are you doing up so late?” he said, shutting the drawer.

“I brought you something to eat.” She held out a bright, shiny apple.

Dorian looked at her for a moment, then chuckled to himself.

“No, thanks. I’m not hungry.”

“What’s funny?”

“Reminds me of something I read, you know, Adam and Eve.”

“I ain’t never done much readin’ myself.”

“Why aren’t you in bed?”

“Jes’ makin’ sure you’re comfortable.” She fanned her face with a piece of cardboard, hoping the mere movement of her hand would make her appear elegant. She adjusted the sleeves on her dress to bring the neckline down lower, exposing her shoulders. With a flicker of her green eyes, her hand moved to the upper part of her dress, thumb and index finger moving along the seam above her breast in a zippering motion. Then her fingertips traveled down provocatively across one breast. “Well, are ya?” Amber continued.

“What?”

“Comfortable.”

“Yes. I’m fine.”

“Mind if I sit down?” she asked, pouting a bit.

Dorian glanced out the window. He appeared worried that they may be seen together. “I was just getting ready for bed,” he said a bit quickly.

Amber paid him no mind. She gracefully settled down in an old wicker-backed chair in front of him, her emerald eyes dancing with delight and curiosity. She studied him for a moment and grinned, sensing he was uncomfortable by her presence, which she seemed to enjoy. Amber had developed a taste for adventure, a chance for a display of flirtation. In the past, she had suffered a lack of attention from boys and wondered if she lacked the sort of fire or self-awareness that would fascinate men. She gave him a pixie’s smile and got up from the wicker chair, sitting quickly on the side of the bed next to Dorian.

“Don’t ya like me?” she asked.

Amber rested her elbow on his shoulder and leaned in front of him, touching his face, rubbing his cheeks with the back of her fingers. Suddenly, Dorian stood up from the bed.

“Yes, I do like you. But it’s late. Maybe you shouldn’t be here?”

“Why don’t ya come here and sit next to me? I won’t bite.”

“Somebody might see you here.”

“Don’t be worrin’ about Billie. Ain’t I as good-lookin’ as she?”

Amber stood and walked to the mirror hanging above the washstand, looking at the reflection of Dorian and herself in the mirror. She took a bite of the apple.

“If a girl eats an apple, while looking in a mirror at midnight, an image of her true love will appear over her left shoulder.”

“Where did you hear that?” Dorian asked.

“It’s true. Ma says stuff like that is jes’ Ozark folklore.”

Suddenly, Billie burst in through the door. She looked at Dorian, then at Amber.

“Ma wants you to come in now, Amber,” Billie said, her arms pressed tightly against her sides.

“She never said no such thing,” Amber replied, aggravated.

“It’s past time you bein’ up.”

“Yer still up.”

Billie started toward the door, then turned to Amber. “I’m tellin’ Pa,” she told her younger sister.

Amber stomped to the door, disgusted. Both Amber and Billie left without looking back.

Relieved to finally be alone, Dorian went immediately to bed, his mind much too occupied for sleep. He laid awake much of the night, pondering the events of the day. The moon was full, and he watched the shadows of a tree just outside the window dance around the room as the night wind stirred the leaves. The last time he had slept was in his familiar bed, the night before going to the Quantum Institute to begin the adventure. The course of two thousand years would pass since he last closed his eyes for sleep.