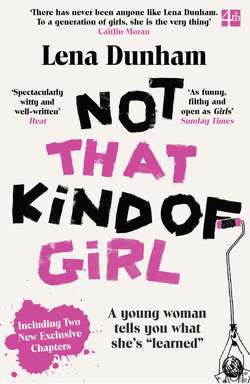

Читать книгу Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She’s “Learned” - Lena Dunham - Страница 10

Оглавление

FOR A LONG TIME, I wasn’t sure if I liked sex. I liked everything that led up to it: the guessing, the tentative, loaded interactions, the stilted conversation on the cold walks home, looking at myself in the mirror in someone else’s closet-sized bathroom. I liked the glimpse it gave me into my partner’s subconscious, which was maybe the only time I actually believed anyone besides me even existed. I liked the part where I got the sense that someone else could, maybe even did, desire me. But sex itself was a mystery. Nothing quite fit. Intercourse felt, often, like shoving a loofah into a Mason jar. And I could never sleep afterward. If we parted ways, my mind was buzzing and I couldn’t get clean. If we slept in the same bed, my legs cramped and I stared at the wall. How could I sleep when the person beside me had firsthand knowledge of my mucous membranes?

Junior year of college, I found a solution to this problem: platonic bed sharing, the act of welcoming a person you’re attracted to into your bed for a night that contains everything but sex. You will laugh. You will cuddle. You will avoid all the humiliations and unwanted noises that accompany amateur sex.

Sharing beds platonically offered me the chance to show off my nightclothes like a 1950s housewife and experience a frisson of passion, minus the invasion of my insides. It was efficient, like what pioneers do to stay warm on icy mountain passes. The only question was to spoon or not to spoon. The next day I felt the warmth of having been wanted, minus the terrible flashes of dick, balls, and spit that played on a loop the day after a real sexual encounter.

Of course at the time I was doing it, I had none of this self-awareness about my own motives and considered platonic bed sharing my lot: not ugly enough to be repulsive and not beautiful enough to seal the deal. My bed was a rest stop for the lonely, and I was the spinster innkeeper.

I shared a bed with my sister, Grace, until I was seventeen years old. She was afraid to sleep alone and would begin asking me around 5:00 P.M. every day whether she could sleep with me. I put on a big show of saying no, taking pleasure in watching her beg and sulk, but eventually I always relented. Her sticky, muscly little body thrashed beside me every night as I read Anne Sexton, watched reruns of SNL, sometimes even as I slipped my hand into my underwear to figure some stuff out. Grace had the comforting, sleep-inducing properties of a hot-water bottle or a cat.

I always pretended to hate it. I complained to my parents: “No other teenagers have to share beds unless they’re REALLY POOR! Someone please get her to sleep alone! She’s ruining my life!” After all, she had her own bed that she chose not to sleep in. “Take it up with her,” they said, well aware that I, too, got something out of the arrangement.

The truth is I had no right to complain, having been affected by childhood “sleep issues” so severe that my father says he didn’t experience an uninterrupted night’s rest between 1986 and 1998. To me, sleep equaled death. How was closing your eyes and losing consciousness any different from death? What separated temporary loss of consciousness from permanent obliteration? I could not face this prospect by myself, so every night I’d have to be dragged kicking and screaming to my room, where I demanded a series of tuck-in rituals so elaborate that I’m shocked my parents never hit me (hard).

Then around 1:00 A.M., once my parents were finally asleep, I would creep into their room and kick my father out of bed, settling into the warmth of his spot and passing out beside my mother, the brief guilt of displacing him far outweighed by the joy of no longer being alone. It only occurred to me recently that this was probably my way of making sure my parents didn’t ever have sex again.

My poor father, desperate to end the cold war that had broken out around sleep in our house, told me that if I retired at nine every night and stayed peacefully in my room he would wake me at 3:00 A.M. and carry me into his own. This seemed reasonable: I wouldn’t have the opportunity to be dead for too many hours by myself, and he would stop yelling at me quite so much. He kept his end up, dutifully rising at 3:00 A.M. to come and move me.

Then one night, when I was eleven, he didn’t. I didn’t notice, until I awoke at 7:00 A.M. to the sounds of our morning, Grace already downstairs enjoying organic frozen waffles and Cartoon Network. I looked around groggily, outraged by the light streaming in through my window.

“YOU BROKE YOUR PROMISE,” I sobbed.

“But you were okay,” he pointed out. I couldn’t argue. He was right. It was a relief not to have seen the world at 3:00 A.M.

As soon as my issues disappeared, Grace’s replaced them, as if sleep disorders were a family business being passed down through the ages. And though I persisted in complaining, I still secretly cherished her presence in my bed. The light snoring, the way she put herself to sleep by counting cracks in the ceiling, noting them with a mousy sound that is best spelled like this: Miep Miep Miep. The way her little pajama top rode up over her belly. My baby girl. I was keeping her safe until morning.

It all began with Jared Krauter. He was the first thing I noticed at the New School orientation, leaning against the wall talking to a girl with a buzz cut—his anime eyes, his flared women’s jeans, his thick helmet of Prince Valiant hair. He was the first guy I’d seen in Keds, and I was moved by the confidence it took for him to wear delicate lady shoes. I was moved by his entire being. If I’d been alone, I would have slid down the back of a door and sighed like Natalie Wood in Splendor in the Grass.

This was not technically the first time I’d seen Jared. He was a city kid, and he used to hang around outside my high school waiting for his friend from camp. Every time I spotted him I’d think to myself, That is one hot piece of ass.

“Hey,” I said, sidling up to him in my flesh-toned tube top. “I think I’ve seen you outside Saint Ann’s. You know Steph, right?”

Jared was friendlier than cool guys are supposed to be. He invited me to come see his band play later that night. It was the first of many gigs I’d attend—and the first of many nights we’d spend in my top bunk, pressed against each other like sardines, never kissing. At first, it seemed like shyness. Like he was a gentleman and we were taking our time. Surely it would happen at some point, and we’d remember these tentative days with a laugh, then fuck passionately. But days stretched into weeks stretched into months, and his fondness for me never took a turn for the sexual. I pined for him, despite sleeping pressed against his body. His skin smelled like soap and subway, and when he slept, his eyelids fluttered.

Despite his indie-rock swagger and access to free alcohol via his job as a bouncer, Jared was a virgin just like me. We found the same things funny (a Mexican girl in our dorm who told us her parents live in “a condom in Florida”), the same food delicious (onion rings, perhaps the reason we never kissed), and the same music heady (whatever he said I should listen to). He was a shield against loneliness, against fights with my mom and C-minus papers and mean bartenders who didn’t buy my fake ID. When I told him I was transferring schools, he teared up. The next week, he dropped out.

At Oberlin, I missed Jared. His midsection against my back. The slightly sour smell of his breath when it caught my cheek. Coagreeing to sleep through the alarm. But it didn’t take me long to replace him.

First came Dev Coughlin, a piano student I noticed on his way back from the shower and became determined to kiss. He had the severe face and impossibly great hair of Alain Delon but said “wicked” more than most French New Wave actors. One night we walked out to the softball field, where I told him I was a virgin, and he told me he had mold in his dorm room and needed a place to crash. What followed was an intense two-week period of bed sharing, not totally platonic because we kissed twice. The rest of the time I writhed around like a cat in heat, hoping he’d graze me in a way I could translate into pleasure. I’m not sure if the mold was eradicated or my desperation became too much for him, but he moved back to his room in mid-October. I mourned the loss for a few weeks before switching over to Jerry Barrow.

Jerry was a physics major from Baltimore who wore glasses, and unusually short pants (shants), and who alternated between the screen names Sherylcrowsingsmystory and Boobynation. If Jared and Dev had been beautiful to me, then Jerry was pure utility. I knew we would never fall in love, but his solid physical presence soothed me, and we fell into a week of bed sharing. He had enough self-respect to remove himself from the situation after I invited his best friend, Josh Berenson, to sleep on the other side of me.

Right on, bro.

Josh was the genre of guy I like to call “hot for camp,” and he had a nihilistic, cartoonish sense of humor that I enjoyed. Despite my practicing “the push in,” the move where you advance your ass slowly but surely onto the crotch of an unsuspecting man, he showed no interest in engaging physically with me. The closest we came was when he ran a flattened palm over my left breast, like he was an alien who had been given a lesson in human sexuality by a robot.

By this point, word was getting around: Lena likes to share beds.

Guy friends who came over to study would just assume they were staying. Boys who lived across campus would ask to crash so that they could get to class early in the morning. My reputation was preceding me, and not in the way I had always dreamed of. (Example: Have you met Lena? I have never met a more simultaneously creative and sexual woman. Her hips are so flexible she could join the circus, but she’s too smart.) But I had standards, and I wouldn’t share a bed with just anyone. Among the army I refused:

Nikolai, a Russian guy in pointy black boots who read to me from a William Burroughs book about cats, his face very close to mine. He was a twenty-six-year-old sophomore who referred to vaginas as “pink” like it was 1973.

Jason, a psych major who told me his dream was to have seven children he could take to Yankees games with him so they could wear letterman jackets that collectively spelled out the team name.

Patrick, so sweet and small that I did let him into my bed, just once, and in the wee hours I awoke to find his arm hovering above me, as if he were too afraid to let it rest on my side. “The Hover-Spooner” we called him forevermore, even after he became known around campus as the guy who poured vodka up his butt through a funnel.

I learned to masturbate the summer after third grade. I read about it in a puberty book, which described it as “touching your private parts until you have a very good feeling, like a sneeze.” The idea of a vaginal sneeze seemed embarrassing at best and disgusting at worst, but it was a pretty boring summer, so I decided to explore my options.

I approached it clinically over a number of days, lying on the bath mat in the only bathroom in our summer house that had a locking door. I touched myself using different pressures, rhythms. The sensation was pleasant in the same way as a foot rub. One afternoon, lying there on the mat, I looked up to find myself eye to eye with a baby bat who was hanging upside down on the curtain rod. We stared at each other in stunned silence.

Finally one day, toward the end of the summer, the hard work paid off, and I felt the sneeze, which was actually more like a seizure. I took a moment on the bath mat to collect myself, then rose to wash my hands. I checked to make sure my face wasn’t frozen into any strange position, that I still looked like my parents’ child, before I headed downstairs.

Sometimes as an adult, when I’m having sex, images from the bathroom come to me unbidden. The knotty-pine paneling of the ceiling, eaten away like Swiss cheese. My mother’s fancy soaps in a caddy above the claw-foot tub. The rusty bucket where we keep our toilet paper. I can smell the wood. I can hear boats revving on the lake, my sister dragging her tricycle back and forth on the porch. I am hot. I am hungry for a snack. But mostly, I am alone.

When I graduated and moved back in with my parents, the bed sharing continued—Bo, Kevin, Norris—and became a real point of contention. My mother expressed distress, not only at having strange men in her house but at the fact that I had an interest in such a thankless activity. “It’s worse than fucking them all!” she said.

“You don’t owe everybody a crash pad,” my father said.

They didn’t get it. They didn’t get any of it. Hadn’t they ever felt alone before?

I remembered seventh grade, when my friend Natalie and I started sleeping in her TV room on Friday and Saturday nights, every weekend. We would watch Comedy Central or Saturday Night Live and eat cold pizza until one or two, pass out on the foldout couch, then awake at dawn to see her older sister Holly and her albino boyfriend sneaking into her bedroom. This went on for a few months, reliable and blissful and oddly domestic, our routine as set as any eighty-year-old couple’s. But one Friday after school she coolly told me she “needed space” (where a twelve-year-old girl got this line I will never know), and I was devastated. Back at home, my own room felt like a prison. I had gone from perfect companionship to none at all.

In response I wrote a short story, tragic and Carver-esque, about a young woman who had come to the city to make it as a Broadway actress and been seduced by a controlling construction worker who had forced her into domestic slavery. She spent her days washing dishes and frying eggs and fighting with the slumlord of their tenement apartment. The conclusion of the story involved her creeping to a phone booth to call her mother in Kansas City, a place I had never been. Her mother announced she had disowned her, so she kept walking, toward who knows what. I don’t remember any specific phrasing except this closing sentence: She wanted to sleep without the pressure of his arms.

For a brief time I was in a relationship with a former television personality who, steeped in the tragedy of early failure, had moved to Los Angeles to make a new life for himself. I was living at a residential hotel in LA, in a beige room that overlooked the garden of two elderly male nudists, and I was lonely as hell and didn’t hate kissing him. He still vaguely resembled a person I had seen on my TV as a tween, and when we went out together, I often watched the faces of waitresses and cabdrivers, looking for a flash of recognition. But kissing was as far as it ever went. He was, he told me, scarred emotionally by a former relationship, a dead dog, and something related to the Iraq War (which he had not, to my knowledge, fought in). I liked his apartment. He had blown-glass lamps, a graying black lab, a refrigerator full of Perrier. He kept his home office neat, a chalkboard with his ideas scrawled on it the only decoration. Driving through a rainstorm one night we hydroplaned, and he grabbed my leg like a dad would. We took a hike in Malibu and shared ice cream. I stayed with him while he had walking pneumonia, heating soup and pouring him glass after glass of ginger ale and feeling his fevered forehead as he slept. He warned me of the life that was coming for me if I wasn’t careful. Success was a scary thing for a young person, he said. I was twenty-four and he was thirty-three (“Jesus’s age,” he reminded me more than a few times). There was something tender about him, broken and gentle, and I could imagine that sex with him might be similar. I wouldn’t have to pretend like I did with other guys. Maybe we would both cry. Maybe it would feel just as good as sharing a bed.

On Valentine’s Day, I put on lace underwear and begged him to please, finally, have sex with me. The litany of excuses he presented in response was comic in its tragedy: “I want to get to know you.” “I don’t have a condom.” “I’m scared, because I just like you too much.” He took an Ambien and fell asleep, arm over my side, and as I lay there, wide awake and itchy in my lingerie set, it occurred to me: this was humiliating, unsexy, and, worst sin of all, boring. This wasn’t comfort. This was paralysis. This was distance passing for connection. I was being desexualized in slow motion, becoming a teddy bear with breasts.

I was a working woman. I deserved kisses. I deserved to be treated like a piece of meat but also respected for my intellect. And I could afford a cab home. So I called one, and his sad dog with the Hebrew name watched me hop his fence and pace at the curbside until my taxi came.

Here’s who it’s okay to share a bed with:

Your sister if you’re a girl, your brother if you’re a boy, your mom if you’re a girl, and your dad if you’re under twelve or he’s over ninety. Your best friend. A carpenter you picked up at the key-lime-pie stand in Red Hook. A bellhop you met in the business center of a hotel in Colorado. A Spanish model, a puppy, a kitten, one of those domesticated minigoats. A heating pad. An empty bag of pita chips. The love of your life.

Here’s who it’s not okay to share a bed with:

Anyone who makes you feel like you’re invading their space. Anyone who tells you that they “just can’t be alone right now.” Anyone who doesn’t make you feel like sharing a bed is the coziest and most sensual activity they could possibly be undertaking (unless, of course, it is one of the aforementioned relatives; in that case, they should act lovingly but also reserved/slightly annoyed).

Now, look over at the person beside you. Do they meet these criteria? If not, remove them or remove yourself. You’re better off alone.