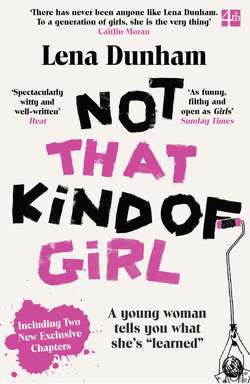

Читать книгу Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She’s “Learned” - Lena Dunham - Страница 15

Оглавление

* Not his real name.

I’M AN UNRELIABLE NARRATOR.

Because I add an invented detail to almost every story I tell about my mother. Because my sister claims every memory we “share” has been fabricated by me to impress a crowd. Because I get “sick” a lot. Because I use the same low “duhhh” voice for every guy I’ve ever known, except for the put-off adult voice I use to imitate my dad. But mostly because in another essay in this book I describe a sexual encounter with a mustachioed campus Republican as the upsetting but educational choice of a girl who was new to sex when, in fact, it didn’t feel like a choice at all.

I’ve told the story to myself in different variations—there are a few versions of it rattling around in my memory, even though the nature of events is that they only happen once and in one way. The day after, every detail was crisp (or as crisp as anything can be when the act was committed in a haze of warm beer, Xanax bits, and poorly administered cocaine). Within weeks, it was a memory I turned away from, like the time I came around the corner of the funeral home and saw my grandpa laid out in an open coffin in his navy uniform.

The latest version is that I remember the parts I can remember. I wake up into it. I don’t remember it starting, and then we are all over the carpet, Barry and I, no clear geography to the act. In the dusty half-light of a college-owned apartment I see a pale, flaccid penis coming toward my face and the feeling of air and lips in places I didn’t know were exposed. The refrain I hear again and again in my head, a self-soothing mechanism of sorts, is: This is what grown-ups do.

In my life I’ve had two moments when I felt cool, and both involved being new in school. The first time was in seventh grade, when I switched from a Quaker school in Manhattan to an arts school in Brooklyn. At Quaker school I had been a vague irritant, the equivalent of a musical-theater kid, only I couldn’t sing, just read the Barbra Streisand biography and ate prosciutto sandwiches, alone in my corner of the cafeteria, relishing solitude like a divorcée at a sidewalk café in Rome. But at my new school, I was cool. My hair was highlighted. I had platform shoes. I had a denim jacket and a novelty pin that said who lit the fuse on your tampon? Boys had other boys come up to me and tell me they liked me. I told one Chase Dixon, computer expert with lesbian moms, that I just wasn’t ready to be in a relationship. People loved my poetry. But after a little while, the sheen of newness faded, and I was, once again, just a B- or even C-level member of the classroom ecology.

The second time I was cool was when I transferred colleges, fleeing a disastrous situation at a school ten blocks from my home to a liberal arts haven in the cornfields of Ohio. I was again blond, again in possession of a stylish jacket—this one a smart green-and-white-striped peacoat made in Japan—and I was showered with attention by people who also seemed to like my poetry.

One of my first self-defining acts, upon arrival, was to join the staff of The Grape, a publication that took undue pride in being the alternative newspaper at an alternative college. I wrote porn reviews (“Anal Annie and the Willing Husbands is weird because the lead has a lisp”), scathing indictments of Facebook culture (“Stephan Markowitz’s party journal is meant to make freshmen feel alone”), and a hard-hitting investigative report on the flooding of the Afrikan Heritage House dorm. One of the editors at the paper, Mike, intrigued me immediately, a six-foot-four senior with Napoleon Dynamite glasses but the swagger of a frat boy and the darkness of Ryan Gosling. He lived in Renson Cottage, a campus-owned Victorian famous for having been the college home of Liz Phair.

Toward the beginning of my Grape career Mike and I dirty-danced at a party, his knee wedged deep between my legs, a fact he seemed not to remember at the next staff meeting. He ran The Grape with an iron fist, verbally abusing underlings right and left, but I passed muster and he often invited me to sit with him in the cafeteria, where he and his tiny Jewish sidekick, Goldblatt, ate plates piled high with lo mein, veggie burgers, and every kind of dry, dry cake. Mike and I were engaged in a constant war of words. It was flirtatious. We worked hard to impress and even harder to seem like we didn’t care.

“I don’t think monogamy can ever work,” he told me one day as we were meeting over cafeteria hash browns.

“I don’t care. I’m not your girlfriend,” I said.

“And thank God for that, toots.”

I giggled. I was something far cooler than a girlfriend. I was a reporter. A temptress. A sophomore.

That winter, I went home for a month with mono, and during that time Mike checked in with me often, under the pretense that he was “struggling, missing my A team over here” and getting pulverized by our rival, The Oberlin Review. On the night of my return, glands still swollen, I wore a vintage wedding dress to dinner with him and Goldblatt at the nicest restaurant in town. Mike smiled at me like we were a real couple (a couple that brought a tiny Jewish sidekick everywhere we went).

A few weeks later Mike came over to my room to watch Straw Dogs.