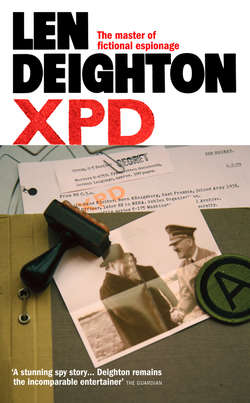

Читать книгу XPD - Len Deighton - Страница 11

Chapter 5

ОглавлениеThe Steins – father and son – lived in a large house in Hollywood. Cresta Ridge Drive provides a sudden and welcome relief from the exhaust fumes and noise of Franklin Avenue. It is one of a tangle of steep winding roads that lead into the Hollywood hills and end at Griffith Park and Lake Hollywood. Its elevation gives the house a view across the city, and on smoggy days when the pale tide of pollution engulfs the city, the sky here remains blue.

By Californian standards these houses are old, discreetly sited behind mature horse-chestnut trees now grown up to the roofs. In the thirties some of them, their gardens blazing with hibiscus and bougainvillea as they were this day, had been owned by film stars. Even today long-lost but strangely familiar faces can be glimpsed at the check-out of the Safeway or self-serving gasoline at Wilbur’s. But most of Stein’s neighbours were corporate lawyers, ambitious dentists and refugees from the nearby aerospace communities.

On this afternoon a rainstorm deluged the city. It was as if nature was having one last fling before the summer.

Outside the Steins’ house there was a white Imperial Le Baron two-door hardtop, one of the biggest cars in the Chrysler range. The paintwork shone in the hard, unnatural light that comes with a storm, and the heavy rain glazed the paintwork and the dark tinted windows. Sitting – head well down – in the back seat was a man. He appeared to be asleep but he was not even dozing.

The car’s owner – Miles MacIver – was inside the Stein home. Stein senior was not at home, and now his son Billy was regretting the courtesy he had shown in inviting MacIver into the house.

MacIver was a well-preserved man in his late fifties. His white hair emphasized the blue eyes with which he fixed Billy as he talked. He smiled lazily and used his large hands to emphasize his words as he strode restlessly about the lounge. Sometimes he stroked his white moustache, or ran a finger along an eyebrow. They were the gestures of a man to whom appearance was important: an actor, a womanizer or a salesman. MacIver possessed attributes of all three.

It was a large room, comfortably furnished with good quality furniture and expensive carpets. MacIver’s restless prowling was proprietorial. He went to the Bechstein grand piano, its top crowded with framed photographs. From the photos of friends and relatives, MacIver selected a picture of Charles Stein, the man he had come to visit, taken at the training battalion at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, sometime in the early 1940s. Stein was dressed in the uncomfortable, ill-fitting coveralls which, like the improvised vehicle behind him, were a part of America’s hurried preparations for war. Stein leaned close to one side of the frame, his arm seemingly raised as if to embrace it.

‘Your dad cut your Uncle Aram out of this picture, did he?’

‘I guess so,’ said Billy Stein.

MacIver put the photo back on the piano and went to look out of the window. Billy had not looked up from where he was reading Air Progress on the sofa. MacIver studied the view from the window with the same dispassionate interest with which he had examined the photo. It was a glimpse of his own reflection that made him smooth the floral-patterned silk tie and rebutton his tartan jacket.

‘Too bad about you and Natalie,’ he said without turning from the window. His voice was low and carefully modulated – the voice of a man self-conscious about the impression he made.

The warm air from the Pacific Ocean was heavy, saturated with water vapour. It built up towering storm clouds, dragging them up to the mountains, where they condensed, dumping solid sheets of tropical rain across the Los Angeles basin. Close to the house, a tall palm tree bent under a cruel gust of wind that tried to snap it in two. Suddenly released, the palm straightened with a force that made the fronds dance and whip the air loudly enough to make MacIver flinch and move from the window.

‘It lasted three months,’ said Billy. He guessed his father had discussed the failure of his marriage and was annoyed.

‘Three months is par for the course these days, Billy,’ said MacIver. He turned round, fixed him with his wide-open eyes and smiled. In spite of himself, Billy smiled too. He was twenty-four years old, slim, with lots of dark wavy hair and a deep tan that continued all the way to where a gold medallion dangled inside his unbuttoned shirt. Billy wore thin, wire-rimmed, yellow spectacles that he had bought during his skiing holiday in Aspen and had been wearing ever since. Now he took them off.

‘Dad told you, did he?’ He threw the anti-glare spectacles on to the coffee table.

‘Come on, Billy. I was here two years ago when you were building the new staircase to make a separate apartment for the two of you.’

‘I remember,’ said Billy, mollified by this explanation. ‘Natalie was not ready for marriage. She was into the feminist movement in a big way.’

‘Well, your dad’s a man’s man, Billy. We both know that.’ MacIver took out his cigarettes and lit one.

‘It was nothing to do with dad,’ Billy said. ‘She met this damned poet on a TV talk show she was on. They took off to live in British Columbia … She liked dad.’

MacIver smiled the same lazy smile and nodded. He did not believe that. ‘We both know your dad, Billy. He’s a wonderful guy. They broke the mould when they made Charlie Stein. When we were in the army he ran that damned battalion. Don’t let anyone tell you different. Corporal Stein ran that battalion. And I’ll tell you this …’ he gestured with his large hands so that the fraternity ring shone in the dull light, ‘I heard the colonel say the same thing at one of the battalion reunions. Charlie Stein ran the battalion. Everyone knew it. But he’s not always easy to get along with. Right, Billy?’

‘You were an officer, were you?’

‘Captain. Just for the last weeks of my service. But I finally made captain. Captain MacIver; I had it painted on the door of my office. The goddamned sergeant from the paint shop came over and wanted to argue about it. But I told him that I’d waited too goddamned long for that promotion to pass up the right to have it on my office door. I made the signwriter put it on there, just for that final month of my army service.’ He gestured again, using the cigarette so that it left smoke patterns in the still air.

Billy Stein nodded and pushed his magazine aside to give his full attention to the visitor. ‘Is it true you pitched for Babe Ruth?’

‘Your dad tell you, did he?’ MacIver smiled.

‘That was when you were at Harvard, was it, Mr MacIver?’ There was something in Billy Stein’s voice that warned the visitor against answering. He hesitated. The only sound was the rain; it hammered on the windows and rushed along the gutterings and gurgled in the rainpipes. Billy stared at him but MacIver was giving all his attention to his cigarette.

Billy waited a long time, then he said, ‘You were never at Harvard, Mr MacIver; I checked it. And I checked your credit rating too. You don’t own any house in Palm Springs, nor that apartment you talked about. You’re a phoney, Mr MacIver.’ Billy Stein’s voice was quiet and matter of fact, as if they were discussing some person who was not present. ‘Even that car outside is not yours – the payments are made in the name of your ex-wife.’

‘The money comes from me,’ snapped MacIver, relieved to find at least one accusation that he could refute. Then he recovered himself and reassumed the easy, relaxed smile. ‘Seems like you out-guessed me there, Billy.’ Effortlessly he retrenched and tried to salvage some measure of advantage from the confrontation. The only sign of his unease was the way in which he was now twisting the end of his moustache instead of stroking it.

‘I guessed you were a phoney,’ said Billy Stein. There was no satisfaction in his voice. ‘I didn’t run any check on your credit rating; I just guessed you were a phoney.’ He was angry with himself for not mentioning the money that MacIver had had from his father. He had come across his father’s cheque book in the bureau and found the list of six entries on the memo pages at the back. More than six thousand dollars had been paid to MacIver between 10 December 1978 and 4 April 1979, and every cheque was made out to cash payment. It was that that had encouraged Billy’s suspicion.

‘I ran into a tough period last autumn; suppliers needed fast repayment and I couldn’t meet the deadlines.’

‘The diamonds that you bought here in town and sent to your contact man in Seoul?’ said Billy scornfully. ‘Was it five thousand per cent on every dollar?’

‘You’ve got a good memory, Billy.’ He smoothed his tie. ‘You’d be a tough guy to do business with. I wish I had a partner like you. I listen to these hard-luck stories from guys who owe me money and I melt.’

‘I bet,’ said Billy. Fierce gusts pounded the windows and made the rain in the gutters slop over and stream down the glass. There was a crackle of static like brittle paper being crushed, and a faint flicker of lightning lit the room. The sound silenced the two men.

Billy Stein stared at MacIver. There was no malevolence in his eyes, no violence nor desire for argument. But there was no compassion there either. His private income and affluent life-style had made Billy Stein intolerant of the compromises to which less fortunate men were forced. The exaggerations of the old, the half-truths of the poor and the misdemeanours of the desperate found no mitigation in Billy Stein’s judgement. And so now Miles knew no way to counter the young man’s calm judicial gaze.

‘I know what you’re thinking, Billy … the money I owe your father. I’m going to pay every penny of it back to him. And I mean within the next six weeks or so. That’s what I wanted to see him about.’

‘What happens in six weeks?’

Miles MacIver had always been a careful man, keeping a careful separation between the vague confident announcements of present or future prosperity – which were invariably a part of his demeanour – and the more stringent financial and commercial realities. But, faced with Billy Stein’s calm, patronizing inquiry, MacIver was persuaded to tell him the truth. It was a decision that was to change the lives of many people, and end the lives of several.

‘I’ll tell you what happens in six weeks, Billy,’ said MacIver, hitching his trousers at the knees and seating himself on the armchair facing the young man. ‘I get the money for the movie rights of my war memoirs. That’s what happens in six weeks.’ He smiled and reached across to the big china ashtray marked Café de la Paix – Billy’s father had brought it back from Paris in 1945. He dragged the ashtray close to his hand and flicked into it a long section of ash.

‘Movie rights?’ said Billy Stein, and MacIver was gratified to have provoked him at last into a reaction. ‘Your war memoirs?’

‘Twenty-five thousand dollars,’ said MacIver. He flicked his cigarette again, even though there was no ash on it. ‘They have got a professional writer working on my story right now.’

‘What did you do in the war?’ said Billy. ‘What did you do that they’ll make it into a movie?’

‘I was a military cop,’ said MacIver proudly. ‘I was with Georgie Patton’s Third Army when they opened up this Kraut salt mine and found the Nazi gold reserves there. Billions of dollars in gold, as well as archives, diaries, town records and paintings … You’d never believe the stuff that was there.’

‘What did you do?’

‘I was assigned to MFA & A, G-5 Section – the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives branch of the Government Affairs Group – we guarded it while it was classified into Category A for the bullion and rare coins and Category B for the gold and silver dishes, jewellery, ornaments and stuff. I wish you could have seen it, Billy.’

‘Just you guarding it?’

MacIver laughed. ‘There were five infantry platoons guarding the lorries that moved it to Frankfurt. There were two machine-gun platoons as back-up, and Piper Cub airplanes in radio contact with the escort column. No, not just me, Billy.’ MacIver scratched his chin. ‘Your dad never tell you about all that? And about the trucks that never got to the other end?’

‘What are you getting at, Mr MacIver?’

MacIver raised a flattened hand. ‘Now, don’t get me wrong, Billy. No one’s saying your dad had anything to do with the hijack.’

‘One of dad’s relatives in Europe died during the war. He left dad some land and stuff over there; that’s how dad made his money.’

‘Sure it is, Billy. No one’s saying any different.’

‘I don’t go much for all that war stuff,’ said Billy.

‘Well, this guy Bernie Lustig, with the office on Melrose … he goes for it.’

‘A movie?’

MacIver reached into his tartan jacket and produced an envelope. From it he took a rectangle of cheap newsprint. It was the client’s proof of a quarter-page advert in a film trade magazine. ‘What is the final secret of the Kaiseroda mine?’ said the headline. He passed the flimsy paper to Billy Stein. ‘That will be in the trade magazines next month. Meanwhile Bernie is talking up a storm. He knows everyone: the big movie stars, the directors, the agents, the writers, everyone.’

‘The movie business kind of interests me,’ admitted Billy.

MacIver was pleased. ‘You want to meet Bernie?’

‘Could you fix that for me?’

‘No problem,’ said MacIver, taking the advert back and replacing it in his pocket. ‘And I get a piece of the action too. Two per cent of the producer’s profit; that could be a bundle, Billy.’

‘I couldn’t handle the technical stuff,’ said Billy. ‘I’m no good with a camera, and I can’t write worth a damn, but I’d make myself useful on the production side.’ He reached for his anti-glare spectacles and toyed with them. ‘If he’ll have me, that is.’

MacIver beamed. ‘If he’ll have you! … The son of my best friend! Jesusss! He’ll have you in that production office, Billy, or I’ll pull out and take my story somewhere else.’

‘Gee, thanks, Mr MacIver.’

‘I call you Billy; you call me Miles. OK?’ He dug his hands deep into his trouser pockets and gave that slow smile that was infectious.

‘OK, Miles.’ Billy snapped his spectacles on.

‘Rain’s stopping,’ said MacIver. ‘There are a few calls I have to make …’ MacIver had never lost his sense of timing. ‘I must go. Nice talking to you, Billy. Give my respects to your dad. Tell him he’ll be hearing from me real soon. Meanwhile, I’ll talk to Bernie and have him call you and fix a lunch. OK?’

‘Thanks, Mr MacIver.’

‘Miles.’ He dumped his cigarettes into the ashtray.

‘Thanks, Miles.’

‘Forget it, kid.’

When Miles MacIver got into the driver’s seat of the Chrysler Imperial parked outside the Stein home, he sighed with relief. The man in the back seat did not move. ‘Did you fix it?’

‘Stein wasn’t there. I spoke with his son. He knows nothing.’

‘You didn’t mention the Kaiseroda mine business to the son, I hope?’

MacIver laughed and started the engine. ‘I’m not that kind of fool, Mr Kleiber. You said don’t mention it to anyone except the old man. I know how to keep my mouth shut.’

The man in the back seat grunted as if unconvinced.

Billy Stein was elated. After MacIver had departed he made a phone call and cancelled a date to go to a party in Malibu with a girl he had recently met at Pirate’s Cove, the nude bathing section of the state beach at Point Dume. She had an all-over golden tan, a new Honda motorcycle and a father who had made a fortune speculating in cocoa futures. It was a measure of Billy Stein’s excitement at the prospect of a job in the movie industry that he chose to sit alone and think about it rather than be with this girl.

At first Billy Stein spent some time searching through old movie magazines in case he could find a reference to Bernie Lustig or, better still, a photo of him. His search was unrewarded. At 7.30 the housekeeper, who had looked after the two men since Billy Stein’s mother died some five years before, brought him a supper tray. A tall, thin woman, she had lost her nursing licence in some eastern state hospital for selling whisky to the patients. Perhaps this ending to her nursing career had changed her personality, for she was taciturn, devoid of curiosity and devoid too of that warm, maternal manner so often associated with nursing. She worked hard for the Steins but she never attempted to replace that other woman who had once closed these same curtains, plumped up the cushions and switched on the table lamps. She hurriedly picked up the petals that had fallen from the roses, crushed them tightly in her hand and then dropped them into a large ashtray upon MacIver’s cigarette butt. She sniffed; she hated cigarettes. She picked up the ashtray, holding it at a distance as a nurse holds a bedpan.

‘Anything else, Mr Billy?’ Her almost colourless hair was drawn tightly back, and fixed into position with brass-coloured hair clips.

Billy looked at the supper tray she had put before him on the coffee table. ‘You get along, Mrs Svenson. You’ll miss the beginning of “Celebrity Sweepstakes”.’

She looked at the clock and back to Billy Stein, not quite sure whether this concern was genuine or sarcastic. She never admitted her obsession for the TV game shows but she had planned to be upstairs in her self-contained apartment by then.

‘If Mr Stein wants anything to eat when he gets home, there is some cold chicken wrapped in foil on the top shelf of the refrigerator.’

‘Yes, OK. Good night, Mrs Svenson.’

She sniffed again and moved the framed photo of Charles Stein which MacIver had put back slightly out of position amongst the photos crowding the piano top. ‘Good night, Billy.’

Billy munched his way through the bowl of beef chilli and beans, and drank his beer. Then he went to the bookcase and ran a fingertip along the video cassettes to find an old movie that he had taped. He selected Psycho and sat back to watch how Hitchcock had set up his shots and assembled them into a whole. He had done this with an earlier Hitchcock film for a college course on film appreciation.

The time passed quickly, and when the taped film ended Billy was even more excited at the prospect of becoming a part of the entertainment world. He found show-biz stylish and hard-edged: stylish and hard-edged being compliments that were at that time being rather overworked by Billy Stein’s friends and contemporaries. He rewound the tape and settled back to see Psycho once more.

Charles Stein, Billy’s father, usually spent Wednesday evenings at a club out in the east valley. They still called it the Roscoe Sports and Bridge Club, even though some smart, real-estate man had got Roscoe renamed Sun Valley, and few of the members played anything but poker.

Stein’s three regular cronies were there, including Jim Sampson, an elderly lawyer who had served with Stein in the army. They ate the Wednesday night special together – corned beef hash with onion rings – shared a few bottles of California Gewürztraminer and some opinions of the government, then retired to the bar to watch the eleven o’clock news followed by the sports round-up. It was always the same; Charles Stein was a man of regular habits. A little after midnight, Jim Sampson dropped him off at the door – Stein disliked driving – and was invited in for a nightcap. It was a ritual that both men knew, a way of saying thank you for the ride. Jim Sampson never came in.

‘Thought you had a heavy date tonight, Billy?’ Charles Stein weighed nearly 300 pounds. The real crocodile-leather belt that bit into his girth and bundled up his expensive English wool suit and his pure cotton shirt was supplied to special order by Sunny Jim’s Big Men’s Wear. Stein’s sparse white hair was ruffled, so that the light behind him made an untidy halo round his pink head as he lowered himself carefully into his favourite armchair.

Billy, who never discussed his girlfriends with his father, said, ‘Stayed home. Your friend MacIver dropped in. He thinks he can get me a job in movies.’

‘Get you a job in movies?’ said his father. ‘Get you a job in movies? Miles MacIver?’ He searched in his pocket to find his cigars, and put one in his mouth and lit it.

‘They’re making a movie of his war memoirs. Some story! Finding the Nazi gold. Could be a great movie, dad.’

‘Hold the phone,’ said his father wearily. He was sitting on the edge of the armchair now, leaning well forward, his head bent very low as he prepared to light his cigar. ‘MacIver was here?’ He said it to the carpet.

‘What’s wrong?’ said Billy Stein.

‘When was MacIver here?’

‘You said never interrupt your poker game.’

‘When?’ He struck a match and lit his cigar.

‘Five o’clock, maybe six o’clock.’

‘You watching TV tonight?’

‘It’s just quiz shows and crap. I’ve been running video.’

‘MacIver is dead.’ Charles Stein drew on the cigar and blew smoke down at the carpet.

‘Dead?’

‘It was on Channel Two, the news. Some kid blew off the top of his head with a sawed-off shotgun. Left the weapon there. It happened in one of those little bars on Western Avenue near Beverly Boulevard. TV news got a crew there real quick … cars, flashing lights, a deputy chief waving the murder weapon at the camera.’

‘A street gang, was it?’

‘Who then threw away a two-hundred-dollar shotgun, all carefully sawed off so it fits under your jacket?’

‘Then who?’

Charles Stein blew smoke. ‘Who knows?’ he said angrily, although his anger was not directed at anyone in particular. ‘MacIver the Mouth, they called him. Owes money all over town. Could be some creditor blew him away.’ He drew on the cigar again. The smoke tasted sour.

‘Well, he sold his war memoirs. He showed me the advertisement. Some movie producer he met. He’s selling him a story about Nazi gold in Germany in the war.’

Charles Stein grunted. ‘So that’s it, eh? I wondered why that bastard had been going around talking to all the guys from the outfit. Sure, I saw a lot of him in the army but he wasn’t even with the battalion. He was with some lousy military police detail.’

‘He’s been getting the story from you?’

‘From me he got nothing. We were under the direct order of General Patton at Third Army HQ for that job, and we’re still not released from the secrecy order.’ He ran his fingers back through his wispy hair and held his hand on the top of his head for a moment, lost in thought. ‘MacIver has been writing all this stuff down, you say, and passing it to some movie guy?’

‘Bernie Lustig. MacIver was going to introduce me to him,’ said Billy. ‘Poor guy. Was it a stick-up?’

‘He won’t be doing much in the line of introductions, Billy. By now he’s in the morgue with a label on his toe. Lustig – where’s he have his office?’

‘Melrose – he hasn’t made it to Beverly Hills or even to Sunset. That’s what made me think it was true … If MacIver had been inventing this guy, he would have chosen somewhere flashier than Melrose.’

‘Go to the top of the class, Billy.’ He eased off his white leather shoes and kicked them carelessly under the table.

‘What was he like, this MacIver guy?’ MacIver had now achieved a posthumous interest, not to say glamour. ‘What was he really like, dad?’

‘He was a liar and a cheat. He sponged on his friends to buy drinks for his enemies … MacIver was desperate to make people like him. He’d do anything to win them over …’ Stein was about to add that MacIver’s promise to get Billy a job in the movie industry was a good example of this desperate need, but he decided not to disappoint his son until more facts were available. He smoked his cigar and then studied the ash on it.

‘Did you know him in New York, before you went into the army?’

‘He was from Chicago. He was on the force there, working the South Side – a tough neighbourhood. He leaned heavily on the “golden-hearted cop” bit. He joined the army after Pearl Harbor and gave them all that baloney about being at Harvard. There was no time to check on it, I suppose …’

‘It was baloney. He as good as admitted it.’

‘They wouldn’t let MacIver into Harvard to haul the ashes. Sure it was baloney, but it got him a commission in the military police. And he used that to pull every trick in the book. He was always asking for use of one of our trucks. A packing case delivered here; a small parcel collected here. He got together with the transport section and the rumours said they even sold one of our two-and-a-half-tonners to a Belgian civilian and went on leave in Paris to spend the proceeds.’ Suddenly Stein felt sad and very tired. He wiped a hand across his face, as a swimmer might after emerging from the water.

‘What are you going to do now, dad?’

‘I lost five hundred and thirty bucks tonight, Billy, and I’ve put away more white wine than is good for my digestion …’ He coughed, and looked for his ashtray without finding it. In spite of all his reservations about MacIver, he was shocked by the news of his murder. MacIver was a con-man, always ready with glib promises and the unconvincing excuses that inevitably followed them. And yet there were good memories too, for MacIver was capable of flamboyant generosity and subtle kindness, and anyway, thought Charles Stein, they had shared a lifetime together. It was enough to make him sad, no matter what kind of bastard MacIver had been.

‘You going to find this Bernie Lustig character?’ said Billy.

‘Is that the name of the movie producer?’

‘I told you, dad. On Melrose.’

‘I guess so.’

‘You don’t think this Lustig cat had anything to do with the killing, do you?’

‘I’m going to bed now, Billy.’ Again he looked for the ashtray. It was always on the table next to the flower vase.

‘If he owed MacIver twenty-five thousand dollars …’

‘We’ll talk about it in the morning, Billy. Where’s my ashtray?’

‘I’ll catch the TV news,’ said Billy. ‘Think they’ll still be running the clip?’

‘This is a rough town, Billy. One killing don’t make news for long.’ He reached across the table and stubbed his cigar into the remains of Billy’s beans.