Читать книгу Reinventing Brantford - Leo Groarke - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 3 | IN ANDREW CARNEGIE’S FOOTSTEPS

In many ways, the plight of downtown Brantford in the 1990s was epitomized by the condition of the 1904 Carnegie Library on the border of Victoria Square. Like much of historic Brantford, the building tied the city to a famous historical figure. Today, Andrew Carnegie is still revered as one of America’s “rags to riches” heroes. In 1848, his family emigrated from Scotland and he found a job working as a bobbin boy in a cotton factory for $1.20 a week. When he retired fifty-three years later, he was famous (and, in the world of unionized labour, infamous) as “the world’s richest man.”

Inspired by a “Gospel of Wealth” that dictated that the rich should help others, the retired Carnegie decided to spend his remaining years giving his wealth away, sometimes worrying that he would fail to do so.1 His most famous gifts were the libraries he established. According to Joseph Frazier Wall, who wrote a biography of Carnegie, his Library Foundation established 2,811 libraries.2 The great majority (1,946 of them) were given to cities across the United States, but 106 were given to Canada. In the spring of 1902, James Bertram, the secretary who oversaw requests for Carnegie library funds, received a letter postmarked Brantford.

Carnegie’s interest in libraries reflected his own experience as a boy, an experience he recounted on a monument he erected in front of the Carnegie Library in Allegheny, New York. The inscription reads:

To Colonel James Anderson, Founder of Free Libraries in Western Pennsylvania. He opened his Library to working boys and upon Saturday afternoons acted as librarian, thus dedicating not only his books but himself to the noble work. This monument is erected in grateful remembrance by Andrew Carnegie, one of the “working boys” to whom were thus opened the precious treasures of knowledge and imagination through which youth may ascend.3

In his autobiography, Carnegie wrote that “This is but a slight tribute and gives only a faint idea of the depth of gratitude which I feel for what he [Anderson] did for me and my companions. It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive of good to boys and girls who have within them the ability and ambition to develop it, as the founding of a public library in a community which is willing to support it as a municipal institution.”4

In Brantford, the first library was organized by Dr. Charles Duncombe in 1835, when he set up the Brantford Mechanics’ Institute. Duncombe, born in Connecticut in 1792, moved to Upper Canada in 1819. Although he lived in Burford Township in Brant County, he also owned property in Brantford. An ardent Reformer, Duncombe became a member of the provincial legislature in 1830, and worked actively in support of progressive ideas in education, prisons, health, and other areas. In 1824, he established Ontario’s first medical school in St. Thomas. In Brantford, the Mechanics’ Institute he founded was located in a small basement downtown and circulated one hundred donated books put on loan to the public. Duncombe sowed the seeds of its and his own undoing in 1837 when he supported the Mackenzie rebellion, gathering a force of five to six hundred men, who quickly abandoned him when they met real troops, failing to achieve anything of significance. In the aftermath, he fled back to the United States.

When Duncombe left, the Mechanics’ Institute closed but it was revived in 1840, and merged with the Zion Church Literary Society in 1866. The church’s minister, William Cochrane, one of the founders of Brantford’s Young Ladies’ College, served as president for twelve years. After a fire destroyed the Institute and most of its books in 1870, it was relocated above an early YMCA building on Colborne. The Institute operated in this location until 1884, when it was dissolved by a city council motion that replaced it with the Brantford Free Library. The motion passed by a decisive majority, though some worried that the library would turn Brantford’s wives into “novel readers.”5

It was Judge Alexander Hardy who brought a Carnegie library to Brantford. A brother of Ontario Premier Arthur Sturgis Hardy, Alexander was a prominent local figure who was dedicated to public education, and to the library in particular. In March of 1902, at a meeting of city council, Alderman J. Inglis forwarded a motion to petition Andrew Carnegie for a library, a city hall, or both. The motion was defeated, but Judge Hardy had already written Carnegie on behalf of the Library Board. In April, Hardy heard back from Carnegie’s secretary, James Bertram, who offered funding of thirty thousand dollars. As soon as the offer was received, any doubts about the building of a library appear to have evaporated, and the project proceeded. On two later occasions, Hardy secured further funding — a visit to New York secured an extra five thousand dollars for the original construction, and a third request, in 1913, secured another thirteen thousand to enlarge the basement.

As planning for the library proceeded, a debate arose over the appropriate location. Newspapers, politicians, and the public participated in a heated discussion over two different sites: their relative costs, which was most suitable for women and children, and so on and so forth. After a great deal of debate and some manoeuvring by vocal members of the public, the newspapers, the city council, and the Library Board, the “park site” on George Street, on the eastern side of Victoria Square, was chosen.

Reverend G.C. Mackenzie, the rector of Grace Anglican and chair of the Library Board, laid the cornerstone for the new library on December 16, 1902. The Brantford Expositor reported that Mayor D.B. Wood spoke at the ceremony, describing “the splendid building that is now being erected and of what it meant to the beauty and progress of the city. The building would be large, spacious, beautiful, ornamental and useful. It would be a building that would rank among the best in Canada for architectural beauty.… Every detail of the building had been gone into … and when the building was completed it would be one of which every Brantfordite would be proud.”6

Ironically, and somewhat unfairly, the official cornerstone recorded the names of the city councillors who voted down Inglis’s motion to approach Carnegie, but not the name of Judge Hardy, who secured the funding. The oversight was not remedied until after his death, when a memorial stone recognizing his role was included in the north side of new library steps.

The finished library, built by Stewart, Stewart &Taylor Architects and Shultz Bros. Construction,7 did not disappoint. The day after it opened, The Expositor reported that “vast sums” had been expended, and that their “careful investigation” had revealed that the “outlay is much greater than was first anticipated.”8 The story hints at public scandal, but not in a way that diminished the paper’s enthusiasm for the finished building: “The new Carnegie library in this city was informally opened, and last evening a very large number of prominent people took advantage of the opportunity to inspect the building.… It presented a unique appearance, and those who saw it from a distance or gave it a critical inspection while going through were more than delighted. The building is complete in every particular.”9

The Expositor’s “Library Notes” of the same day reported that “The free library opened yesterday and was crowded as a result, all day long. Hundreds visited the building and expressed themselves as delighted with the interior furnishings. The library is certainly fitted up in magnificent shape and everything has been done with a view to the comfort of the patrons.” The only negative note sounded complained of some “considerable trouble” with “dogs which were brought in.” To ensure no similar problems in the future, a new library regulation prohibiting dogs in the building was immediately established.

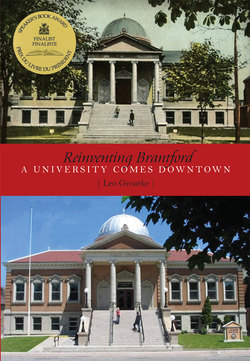

Right from the start, the Brantford library was recognized as one of Canada’s finest examples of the Beaux Arts style that it embodies. Situated on the edge of one of the country’s finest Victorian squares, its architectural details included a mansard roof, a dome, and a grand entrance. The entrance was set in a large portico at the top of a long, imposing stairway. At the top of the stairs, four Ionic columns supported a triangular pediment in front of the building’s dome. The interior featured archways, pillars, a mosaic, and a rotunda with a stained glass skylight with Islamic tracery situated underneath the dome. Above the main entrance, the builders inscribed a boast from Virgil, who wrote, “I have erected a monument more lasting than bronze.” The names Shakespeare, Dickens, Milton, Tennyson, Burns, and other English-speaking writers were embossed in pediments above the first floor windows.

Lavish details like those in the Brantford library were common in Carnegie’s early buildings. It is not clear what his secretary, James Bertram, thought of the details of the Brantford library, but he grew impatient with cities which, in his opinion, spent Carnegie’s money on unnecessary architectural embellishments. In 1911, he issued a pamphlet entitled Notes on the Erection of Library Buildings, which included written advice and standard designs, and warned against “aiming at such exterior effects as may make impossible an effective and economical layout of the interior.” The pamphlet was sent to municipal authorities when they were notified that they had received a Carnegie grant. Looking at the library in Brantford, one wonders if Bertram was too concerned about architectural extravagances, for the fine details of the Brantford building very successfully confirmed its significance.

Details of the Brantford Carnegie Library. The quote from Horace above the front entrance translates as “I have built a monument more lasting than bronze” — Odes, 3.30.1. The 1902 cornerstone commemorates the dedication of the library. In 1956, when the stairs were redone, a stone inscription was added to recognize Judge A.H.Hardy’s role arranging Carnegie funding.

In downtown Brantford, the Carnegie Building housed the public library for almost ninety years. It served, not only as a centre for reading and the borrowing of books, but as a place of culture and public education, sometimes serving as a home for the city’s museum, archives, and art gallery. During its tenure as the public library, the building was one of Brantford’s most successful public buildings, but it was showing signs of wear by the 1980s. In 1979, the public library’s chief librarian, Lavinka Clark, complained that “the premises have been put to the fullest possible use and the building is grossly inadequate for our ever-expanding needs and programs beneficial to the public.”10 After repeated entreaties, complaints, and submissions to city council, it agreed to move the public library.

The Carnegie Building was closed in December 1991. Its impressive exterior remained, but the interior of the building was worn out from almost ninety years of constant wear and tear. The Brantford Public Library was moved to less elegant but more spacious premises in an empty Woolco store on Colborne Street. The library won an award for its clever renovation of its new building. In other cities, vacated Carnegie libraries were converted into banks, office buildings, law offices, government buildings, and even private homes, but the architectural masterpiece that Carnegie gave Brantford sat empty and forlorn, unable to attract a tenant. Local rumours suggested that the building would become a provincial courthouse. The president of the Historical Society, David Judd, proposed that it become the home of the Brant County Museum and Archives.11 He was successful in attracting some support but not the necessary funding. At one point the city put the building up for sale and a local firm, MMMC Architects, looked at a possible renovation on behalf of a private insurance group. In 1996–97, the city considered turning the building into offices for the Planning and Building Department.

As the 1990s progressed, the building seemed to have no future. The future of its setting seemed even bleaker. On one side of the building, the harsh aesthetics of the 1967 city hall undermined the historical integrity of Victoria Square. On the other side, the integrity of the square was being challenged by a new owner who had bought Park Church and decided to demolish it in favour of a parking lot. As Peter Muir wrote in Brant News:

The Carnegie building is part of an impressive grouping of buildings that surround Victoria Square in the centre of Brantford. The “neo-classical” building with its temple like front steps, massive pillars, domed hall and mosaic floor, now sits vacant and lifeless beside Park Church.

The Church has brought attention to the fate of “one of the most impressive public squares in the Province of Ontario.” It has been granted a temporary reprieve from the wreckers’ ball but is slated for destruction in the spring. The Carnegie building may be next on death row. It has been empty for three years and needs work if a suitable tenant is to be found.12

These were difficult times for Brantford’s most historic square. The old YWCA and Old One Hundred were already gone. The city hall had not retained any vestiges of heritage. The Carnegie Building had been vacant for almost a decade. Park Church was slated for demolition. The impressive home that E.L. Goold had built across the street from Park Church was in a state of serious disrepair. And the decline on the perimeter of the square was compounded by the deterioration in the buildings that lined the blocks surrounding it.

Park Baptist Church, beside the Carnegie Library, circa 1900–05. The church was saved from demolition only when the province assigned it a heritage designation in recognition of its unique stained glass window above the vestibule. The building now houses Brant Community Church.

In the midst of these discouraging circumstances, the Brantford Heritage Committee initiated a push in a better direction. In a context in which most of Brantford favoured the demolition of the old buildings downtown, it opposed such action and did its best to save the architectural heritage that could still be found in downtown Brantford. The committee found a way to save Park Church from the wreckers’ ball by securing a provincial heritage designation that prevented its new owner from demolishing the building. The designation was awarded in order to preserve the unique circular stained glass window on the front of the church. With the church saved, at least for the foreseeable future, one could not help but wonder whether the former Carnegie Library, so long a sign of Brantford’s prominence but now quickly deteriorating, might be saved as well.