Читать книгу Reinventing Brantford - Leo Groarke - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| FOREWORD |

by William Humber, Seneca College

We all cherish well-loved places, be they scenic vistas, an apple orchard on the edge of town, a character-filled old building, or a favourite fishing hole. Then one day they’re gone and we sigh and reflect that this must be the price paid for that dreaded, non-contestable phenomenon called progress. It is amazing how accepting we are of such actions that seem so devastating.

One person who noticed and decided to write about it was Storm Cunningham, one of the world’s leading advocates of restoration. He is an avid scuba diver, but realized that his visits to some of the pristine waters of the world were too often a hollow reminder of how things had only got worse with time, including decaying coral reefs, loss of diverse fisheries, and the disappearance of quaint local lifestyles associated with such places. Then about ten years ago he noticed a startling change, at least in some places. Plans and actions were actually contributing to an improved world.

He originally set out to write a book on how that grand but illusive theme of sustainability must be the reason for this more hopeful world. But in investigating its practice he made a stunning discovery. Too often sustainability proved to be no more than a stop-gap measure by which preserving a little piece of property here, a green building there, or temporarily protecting a tiny living thing in the path of a freeway, were simply small thumbs in the dyke of irreversible damage — smokescreens for greater devastation rationalized by the “greening” of some built or natural feature, but achieved by depleting or eliminating another.

He recognized that an environmentally acclaimed new community built on a former wetland, or an accredited green building on a rural, agricultural site reachable by any reasonable measure only by car, were problematic and ultimately unacceptable responses to the loss of biodiversity, climate change, and the degradation of once-loved places. As a result, Storm’s first book, The Restoration Economy, told a far different story than he originally intended. It began with a significant history lesson. “For some five thousand years,” he wrote, “much of humankind, especially Western civilization in the past five centuries, has been in a pioneer mode of development that sustains economic growth by developing raw land and extracting virgin resources. New lands and virgin resources, however, are rapidly becoming myths from a bygone era.”1

He then described the second phase of the three-stage growth cycle as being that of maintenance and conservation, in which humans tackle challenges of breakdown in their built and natural environments through increasingly patchwork strategies — for instance, preserving small wooded areas disconnected from the necessary routes living things need to move from one place to another, or refurbishing older buildings without attention to the economic catastrophe surrounding them.

Today he argues we are confronting three crises as a result of this development style. These include contamination, in which a majority of soil around the world is degraded and oceans are increasingly acidified and filled with toxic waste such as carelessly disposed-of pharmaceuticals and plastic detritus; corrosion, in which much we currently build is virtually garbage the first day it is occupied; and constraint, in which we suddenly find that our magical gift for generating new solutions for resource depletion is running up against a world challenged by peak oil, the loss of biodiversity, and potential food shortages.

We are left with little choice but to enter into the third stage of development, namely restoration. It is a comprehensive and integrated approach to restoring the integrity and interconnectedness of built and natural environments. We do so despite living in a world still engaged in pioneer modes of development. In the process we continue to deplete limited resources, overwhelm ecosystems, destroy downtowns, and empty countryside locations that have provided comfort to their inhabitants but less apparent value to their despoilers.

Dams are still being built, landscapes flooded and tar sands mined, though in the case of the latter, the cost reflected in cleaner energy used for this purpose and fresh water expanded might, if ecosystem services were properly calculated, challenge the economic merit of such a project. So while there has been a great human shift from nomadic to settled existence, we still live as if we are nomads, damaging the places we live and moving on. Except that now there is nowhere to move. The carbon-based economy, which allows us to off-shore cheaper production to China, haunts all of us.

Restoration on the other hand is premised on bringing places back to life, creating new value and employment opportunities, and enticing investment, which asks only what way the market is going and spends its dollars accordingly. Its magic lies in the way it includes market-based integration with a deliberate uplift of the soul. A philosopher such as Leo Groarke might call this a “metaphysics of restoration.” It is predicated on leaving places better than we found them, an approach taking us far beyond new development models equating economic growth with conquering new lands and extracting virgin resources. Restorative development is an economically resilient model that understands, for instance, that the eventual cleanup of a gold mine or nuclear facility should include the site’s necessary restoration to have a true picture not only of the project’s complete cost but also its opportunity.

It reflects a shift from artificial and simple static mechanical models to complex dynamic living ones. It recognizes the messiness of reality and the challenge of finding tools to begin modelling it. It celebrates an ability to differentiate, select, and amplify multiple options.

It acknowledges that what briefly benefits a few now may poison everyone’s children for a long time. All restorable human-made assets were, of course, originally created by what Cunningham calls “dewealth” activities, which failed to recognize the value of perpetual ecosystem services, such as air, water, and wildlife. Nor did they account for nature’s regenerative powers characterized by its ability to break down harmful compounds and sequester harmful elements. For most of human history this approach was manageable and even acceptable though we now know that civilizations have disappeared because of their failure to appreciate their resource limitations.

In our advanced western societies this harmful decoupling of the economy from its resources dates back to Adam Smith. Neoclassical economists following in Smith’s path have argued that as a resource becomes scarce its price will increase, providing incentives to develop substitutes. But when we depend on non-market-based ecosystem services, which have no price (such as climate, clean water, and waste absorption) and these become increasingly scarce, there has been no market incentive to produce or restore them — until now, that is.

Increasingly, our success stories will have to combine economic and environmental initiatives in community revitalization such as infrastructure improvements, a hierarchy of energy and water demand and supply side strategies, and neighbourhood revitalization for greater mixed use, heritage re-use, and mobility options; along with natural resources restoration, such as reclaiming waterfronts, reintroducing riverbeds, or upgrading groundwater sources. These not only allow for maximum utility of limited resources but, by the integrating multiple elements of the built and natural environment, enhance financial advantage for a long-term return on initial investment.

Ultimately, such an approach could provide Ontario with leading edge expertise in successfully addressing issues of water management and community decline within the cross-border Great Lakes Region. It also has global application by its potential to create a knowledge base of professionals who demonstrate that Ontario is a place for leadership in revitalization, akin to that of Silicon Valley for the information technology industry.

This compelling restoration story involving the City of Brantford and Laurier Brantford makes explicit what is already being practised in so many places, but it is only now entering the broader public conversation. Until now, environmentalism, greening, and sustainability have been the common reference points for this discussion, but each of these has in its own way become part of the silo thinking that reduces their use to that of special interests and “nice to haves.” They have been critiqued as being essential to most people’s lives only when they have reached a certain degree of personal comfort. Environmentalism has become, and perhaps always was, a lifestyle movement within advanced western industrial countries, with little relevance to depressed parts of the world.

Restoration, and its complement of re words including revitalization, regeneration, renewal, and redevelopment, on the other hand, link, indeed embed, environmental imperatives within an economic development context, and therefore more robustly recognize the real potential for a more mature understanding of the relationship between what have been seen as contradictory ideas — improving the environmental character of the world while making money.

Restoration, Cunningham says, is the “sweet spot” of sustainability where we can actually measure the enhancement of our built and natural resources, rather than the depletion of one in service of another. The challenge is moving this insight from the level of storytelling to that of real, on the ground proposals for improvement consistent with revitalization. Increasingly jurisdictions from municipalities to regions and national governments are beginning to understand the need for resiliency in their public policies, particularly as the reality of climate change, global economic competition, and loss of local biodiversity impinge daily on their former “business as usual” responses. Ontario’s Places to Grow strategy, based on maintaining and enhancing the character of its rural and countryside locations for the purposes of agriculture, watershed protection, and scenic amenity, is aligned with the goal of intensifying growth and population in existing urban areas.

A restorative development strategy clearly benefits both of these goals. On the one hand it supports measures for agricultural transformation to higher-end commodities that are healthier, more value-laden, and, in the bargain, taste better and can be delivered locally, while responding to climate change through reforestation of damaged lands. Such a strategy supports watershed enhancement through restorative measures that improve the quality and access to drinking water while revitalizing fisheries and ultimately the health and long-term sustainability of the Great Lakes. It maintains and enhances the scenic, and with it the tourist potential inherent in features such as the Oak Ridges Moraine and the Niagara Escarpment.

From an urban perspective the value of restoration is even more pronounced. Yet many of our urban places are dispiriting in quality either because of their low density, single use, automobile-dependent, disconnected street character, or because those in inner cities and their surrounding post-war suburbs have experienced several generations of out migration, becoming in the process places of last resort either for long-time citizens at the bottom of the economic scale or new immigrants looking for a toehold in the Canadian economy. The revitalization challenge for the latter places has been recognized by agencies as diverse as the United Way and the Canadian Urban Institute. They have supported or engaged in a more deliberate policy and practice of neighbourhood-based intervention in everything from community support resources such as jobs and shopping places, to transit and place-making improvements such as heritage recognition. The commonly used term of regeneration as practised in the United Kingdom provides a model for such activity.

Just as problematic, however, are the single-use, low-density, car-dependent places generally at some remove from the places people work, play, and shop. This broader realm of interaction has become the existential terrain of people’s lives. The mortgage fiasco in the United States, the often short-term life expectancy of contemporary constructed projects, and the galloping cost of fuel and its likely peak oil character are creating a perfect storm of almost invisible catastrophe for such places within what is acknowledged to be the broader “megapolitan” modern city reality (Toronto, for instance, has effectively become an area defined at minimum by Orillia in the north, Peterborough and Belleville in the East, Waterloo in the West, Brantford in the southwest, and St. Catharines around the lake). Revitalization of such places has become an urgent public priority.

Cunningham’s recipe, spelled out in greater detail in his latest book reWealth2 indicates that a restorative strategy must account for the integration of four elements of the built environment — heritage, infrastructure, brownfields, and places harmed by catastrophe, along with four elements of the natural — fisheries, agriculture, ecosystems and watersheds, and finally with the socio-economic elements of schooling, services such as public safety, culture, and commerce. Their successful integration works best within a non-partisan renewal coalition standing outside normal electoral cycles, and it should be managed by creative partnerships between public and private interests.

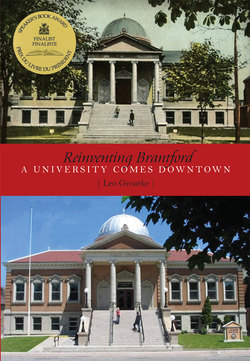

Above all, restoration requires hard examples that can inspire and provide a foundation for manufacturing new opportunities. The Brantford experiment is one of the best in southern Ontario. Its frustrations included a lack of provincial support, changing local administrations, and hard choices faced by university decision-makers conscious of their primary mission to deliver education. Town heritage advocates have had to recognize that preservation might not always be feasible but the values of past models such as streetscape integration, human scale models, and architectural detailing could be replicated in the new with careful planning. Wilfrid Laurier University’s triumphant visionary approach in restoring the heritage built environment of Brantford, and in so doing revitalizing a downtown that a former mayor had once called the worst in Canada, are exemplary.

New investment has followed Wilfrid Laurier into the downtown, the vibrant presence of students has rejuvenated a once sad place, and a wider audience of citizens and public authorities have been instilled with a sense that good things can happen with the right vision. These benefits have followed the University’s bold commitment to what Leo Groarke calls “a new kind of economy.” It is one no longer dependent on sprawl and short-term retail big-box models either outside of the old town or in its downtown.

Brantford has become a poster child for the magic of restorative development.

William Humber

Leader of Seneca College’s outreach in urban sustainability and regional renewal

Toronto, Canada.