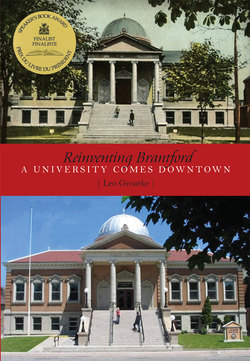

Читать книгу Reinventing Brantford - Leo Groarke - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 5 | CHASING “UBC”

Even in the tough times, Brantford has enjoyed a strong identity. In the campaign to establish a university, this expressed itself in a desire to have a university of its own. Everyone in Brantford nods knowingly when I tell them that there are those in Brantford who did not want a satellite campus of Laurier or some other existing university but a new “UBC”— a University of Brant County.

In the quest for a university, the local desire to have a Brantford institution was manifest in a proposal to establish a private university. This was a radical idea in a country which defines university education in terms of public institutions. In this respect, Canadian education has developed in a different way than its American counterpart, where some of the nation’s best known universities — Harvard, Yale, Stanford — are privately funded institutions. The idea that Brantford should have a private university proposed a new educational paradigm for Canada, but this was not what motivated the city. From its point of view, the plan to found a private university was not an attempt at educational reform, so much as an attempt to circumvent a system of publicly funded institutions which excluded Brantford. One way or another, those who wanted a local university were bound and determined to secure one. If this meant breaking the mould that defined university education in Canada, this was fine with them. To some of those involved, this made the proposal more attractive.

But the proposal for a private university did not begin as a Brantford initiative. It was an idea forwarded by three renegade arts professors who were inspired by a desire for educational reform. Gordon Morrell, Edmund Pries, and Ronald Sawatsky were part-time professors at the University of Waterloo. Morrell and Pries were members of an ever-expanding army of part-time faculty who worked at Canadian universities. Squeezed between limited provincial funding and the demands of full-time faculty, universities increasingly relied on part-timers, who were paid a fraction of the salary of full-time professors, taught larger classes, and did not enjoy the security and the benefits that accrue to tenured faculty (benefits that included sabbaticals and research opportunities). This was a difficult lot for part-timers who had successfully survived the rigours of a Ph.D. in the hopes of full-time employment. In a situation where some of them engaged in the research associated with a job as a professor more than their full-time counterparts, it was difficult, even unjust, to have to endure working conditions so inferior to those of their full-time colleagues. The more radical decried “tenure as injustice” and described themselves as the “lumpenproletariat” of the academic workforce, a term that Marx used to described the rabble that makes up the bottom layer of the working class.

Andrew Toos on the evolution of the academic, a parody on the traditional illustration of “the evolution of man.” Like the original, it assumes a male stereotype.

Most part-time professors toiled in the hope that they would eventually land a full-time position. Many did. Others organized unions to fight for better working conditions for part-time faculty. In Kitchener-Waterloo, Morrell, Pries, and Sawatsky came up with a radically different strategy. Instead of working as perpetual part-timers in an existing university, they decided to launch an initiative to establish an institution of their own. They wanted a model that could compete with existing universities and decided that it would be a small liberal arts institution that would offer a different model of education than the one that characterizes Canadian universities. Like private liberal arts colleges in the United States, the City College they first proposed for Kitchener was designed to emphasize teaching over research, general education, undergraduate rather than graduate programs, student/professor interaction, and, in the spirit of humanism, the development of the whole person. When the Kitchener option did not work out, they partnered with Brantford. The partnership was a marriage of two outsiders: a city and a group of part-time faculty determined to do an end run around existing universities in their attempt to find a way into the Canadian university system.

Even before it came to Brantford, the City College Project had attracted national media attention. At a time when a Conservative government in Ontario was seriously considering the possibility of private universities, the City College proposal was swept into a heated debate which pitted the City College group and others who wanted private universities against the existing public universities and their faculty associations. The locus of the debate moved to Brantford after two members of the Education Committee of a local development board,1 Doug Brown and Vyrt Sisson, heard Gordon Morrell interviewed on a national radio broadcast. In a situation in which the Brant strategic plan had already flagged a local need for more post-secondary education, Brown and Sisson were intrigued by the idea of a private university and arranged for Morrell and his two colleagues to speak to their committee. Unable to establish the college they wanted in Kitchener, the City College group was determined to make the most of the Brantford opportunity. When they met with the education committee on September 20, 1996, they requested $291,000 to establish a private college. In return for the funding, which would be used to pay for salaries, a marketing plan, and the development of a curriculum, they promised to open the college in September 1997.

At a special meeting on October 10, 1996, the local board enthusiastically noted that the proposed college was in keeping with other Brantford initiatives (among them, the plan to move Mohawk College downtown) and encouraged the education committee to pursue the idea further. The board was less enthusiastic about the proposed price tag, which they thought extravagant and not well worked out. One of the key board members, a retired bank manager, told me that the City College professors did not know how to write a business plan. He raised his hands, looked to heaven, smiled, and quipped: “What can you expect from arts professors who haven’t studied business?” (In the wake of the collapse of the North American stock market after questionable business practices in 2008, I poked him in the ribs and asked him: “What can you expect from business leaders who haven’t studied ethics?”)

The Board offered the City College professors fifteen thousand dollars to prepare a preliminary plan for a private university. They accepted the offer and submitted a University College of the Grand Valley:Business Plan two months later. The “Executive Summary” outlined an ambitious plan to establish a university “in the heart” of downtown Brantford.

The City College Project Group-Brant, in cooperation with Brant Community Futures Development Corporation, plans to develop an accredited university college, University College of the Grand Valley (UCGV), in the heart of the City of Brantford by September 1, 1997. UCGV will become one of the first private, tuition-driven, liberal arts colleges in Ontario. This model, based on other similar institutions in British Columbia and Alberta, as well as the United States and Great Britain, is a new model for Ontario post-secondary education. UCGV is not intended to supplant the existing public post-secondary education system, but rather to supplement it and to increase the options available to students.2

In explaining why a private university should be established, the plan emphasized Brant County’s low level of educational attainment, the need to avail local students with access to a university, and the economic and cultural benefits of a university. The mission statement for University College of the Grand Valley was committed to “a high quality undergraduate university degree with a strong emphasis on creative teaching, smaller classes, a high degree of professor-student interaction, and experiential learning.” It promised that UCGV would “be an active participant in the Brantford community, culturally, intellectually and economically.”

The City College’s forty-three-page business plan attempted to work out, in a more detailed way, how a private university would operate. The plans included a proposed liberal arts curriculum,3 library services provided in partnership with the Brantford Public Library (a plan discussed with Wendy Newman, the Library’s CEO), an agreement with Mohawk College that would allow college students to transfer to degree programs, and suggested linkages with the downtown YMCA (to provide recreational facilities) and the Woodland Cultural Centre, a Brantford institution that houses one of Canada’s largest repositories of aboriginal artifacts. In its discussion of possible locations, the City Group had no doubts about their preference. The empty Carnegie Library had caught their eye, convincing them that an association with the history and heritage of the downtown could be a key component of the new college. “It is the goal of UCGV to locate in the heart of the old City of Brantford. UCGV hopes to contribute to the ongoing process of the revitalizing of the downtown core of Brantford…. To date, the Carnegie Library is the best and most appropriate building which may be available for use.”4

In a rudimentary way, the College of the Grand Valley business plan successfully addressed the issues that a new university would have to face in Brantford. But it faced a major obstacle. To function as a university it would have to be accredited by the government in a province that had no tradition of secular private colleges. In attempting to navigate a way around this problem, one of the City College professors, Edmund Pries, met with administrators from the University of Waterloo, proposing an affiliation. When the university’s president, James Downey, told them that Waterloo would not be interested until City College had an established reputation, Pries told him that the college wouldn’t need an affiliation when it reached that point. As a clever but improbable alternative to Waterloo, the business plan proposed an affiliation with Northland Open University, a somewhat shadowy correspondence university which was incorporated in Whitehorse, Yukon, in 1976, but ceased its operations. In lieu of an agreement with an existing university, the College business plan proposed a direct application to the Ontario government.

In view of financial and accreditation concerns, the Brantford development board that had commissioned the College of the Grand Valley business plan decided that it would not release it to the public, but use it as a basis for a revised plan that would include additional details. To keep the initiative going, they hired John McGregor, who had coordinated the Brant Community Strategic Plan, and formed a University Committee to work with him.5 In an attempt to establish some momentum, McGregor personally contacted sixty prominent Brantford citizens. In December 1996, shortly after the College of the Grand Valley business plan was presented to the board, the Ontario Premier’s Advisory Panel on Future Directions for Postsecondary Education raised the hopes of McGregor and the committee when it recommended that the Degree Granting Act of 1983 be amended to allow the province to accredit private universities. McGregor and others travelled to Toronto to discuss Brantford’s plan to establish a private university and were told (by the deputy minister of training and education) that the City College proposal looked “excellent,” but that it could not be supported immediately, and would have to wait until provincial legislation was changed to allow for private universities.

McGregor and the University Committee made some significant attempts to mobilize support for the Grand Valley initiative. With the help of the local member of Parliament, Jane Stewart, McGregor and his committee established the Grand Valley Education Society (GVES) as a charitable organization to raise money for their new initiative. Ontario’s former minister of education, Bette Stevenson, was contacted. She was sympathetic to the project but was already engaged in a similar venture in Newmarket, where she was helping David Strangway, the former University of Toronto and University of British Columbia president, who was attempting to establish a private institution called Wolfe University. Strangway’s experience at two of Canada’s major universities made him a passionate advocate for the kind of education provided by private liberal arts institutions: an interdisciplinary education focused on high quality undergraduate teaching. When the Newmarket project did not succeed, Strangway took his mission to British Columbia, where Quest University became Canada’s first accredited secular private university in 2005.

The Grand Valley Education Society played a central role in bringing the university to Brantford. Key members pose outside the GVES office: (left to right) Susan Vincent, Colleen Miller, Stuart Parkinson, Vyrt Sisson, Bruce Hodgson, and Douglas Brown.

After months of work on their project, the Brant University Committee decided it needed to mobilize public support for the founding of a private university. It announced a public meeting that took place in September 1997, the month originally proposed for the opening of the new university-college. The meeting inaugurated a series of public meetings that discussed all aspects of the project — the need to raise eight hundred thousand dollars in start-up funds; the character of the proposed college (specializing in small classes, emphasizing teaching and student-professor interaction); and possible locations (a number of sites were proposed). The publisher of The Expositor, Michael Pierce, promised to support the committee by sending a reporter to all public meetings.

The Bell Building on Victoria Square was one of the buildings suggested as a home for University College of the Grand Valley. After Laurier arrived, the university had positive discussions with Bell Canada over its use. The discussions came to an end when security restrictions the company introduced in the wake of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York would not permit public access to the building.

A few weeks before the first meeting, the city’s most outspoken councillor, John Starkey, published an Expositor article entitled “Brantford Needs a University.” Comparing the economic woes of Brantford to those of Newfoundland, he singled out Brantford’s lack of a university: “Unlike all of our principal neighbors, we have no university. And so the city looks to a future without the best, the brightest, the most ambitious, the most determined, the most fortunate. Brantford’s youth is taught that the road to success is a one-way route out of town to someplace with a university.”6

Starkey went on to support the University College of the Grand Valley, favouring the vacant Carnegie Library as the right place for its campus: “The opening of Brantford’s ‘University College of the Grand Valley’ is an event of exciting promise. Follow the announcements as they are made. And when the call goes out for volunteers and donations, work hard and dig deep.”7

The Expositor contributed to the momentum with an editorial entitled “School of Hard Knocks.” Observing that “to date the community seems less than inspired by the idea” of a private university, it granted that “It is certainly understandable that there would be a certain amount of healthy skepticism about the plan. For one thing, this is Brantford, where the unofficial motto is “I’ll believe it when they open the doors.”8

The Expositor itself begged to differ: “For decades Brantford has felt inadequate because it lost out during the explosive period of university growth in the 1960s. Subsequent attempts to develop a university presence in Brantford in conjunction with existing universities have largely been unsuccessful. So, if half-measures have failed to work, why not go all the way and dream big — the University College of Grand Valley? There’s little to lose, and the potential rewards are great.”