Читать книгу Staging Ground - Leslie Stainton - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

No building is static, least of all a theater, whose primary aim is the telling of stories and whose occupants are, for the most part, transients. The Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is particularly mutable. One of the oldest continuously operating theaters in the United States, its history spans at least two centuries, arguably more. For decades I wanted to tell its story—but I wrestled with the problem of how to do so without resorting to numbing detail. A mere account of the more than ten thousand performances that took place in the Fulton from 1852 to the present—never mind its hundred-year existence as a jail prior to 1852—would not begin to convey the complexity of the place, or the Fulton’s significance in the larger story of a young nation struggling to forge an identity. Nor would it capture the bewildering array of personalities who in ways big and small etched their tales into the fabric of this space—from dour James Buchanan and steamy Victoria Woodhull to Richard Jackson, a fugitive slave who in 1825 awaited his fate in what is now the Fulton basement, and the late Michael Mitchell, artistic director of the Fulton from 1999 to 2008, who in his last months of life said he was “at peace,” despite a grave illness, because he had lived his life “in places like this. Grand spiritual enterprises.”

In my search for a way to structure the unruly story of this great American theater, I eventually settled on a framework of two distinct but complementary narratives: the story of Blasius Yecker, who ran the Fulton during its heyday as an American roadhouse, from 1866 until his death in 1903, and whose experience as an immigrant-turned-entrepreneur-and-civic-leader struck me as quintessentially American; and the story of my own coming of age in the 1970s and ’80s, a period when the Fulton reclaimed its status as a venue for live plays, and I worked in the theater as an actress, stagehand, seamstress, office assistant, and member of a children’s theater company. “All history is biography,” said Emerson. That truism underpins much of this book.

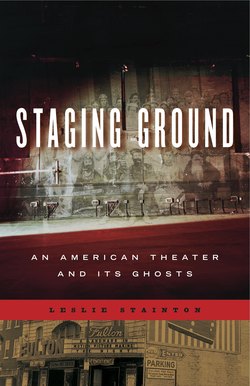

Staging Ground is thus both a history and a memoir. I am far from alone in feeling a personal attachment to this building, and my hope is that by filtering the Fulton’s larger story through the smaller lens of my own, I can shed light on both the public and private meanings of this extraordinary space—and convey some sense of the intricate ways that the past and present overlap inside its walls. I could have written about any of the nearly four thousand theaters that existed in towns across America in the late nineteenth century and that shaped the way Americans saw and thought about themselves. Fewer than three hundred of these buildings survive, and most occupy a special place in their communities, as they should. Whether they’ve been lavishly restored or merely spared from the wrecking ball, these are all haunted houses. But the Fulton Theatre has long seemed to me uniquely ghosted—not just because it’s in my hometown or because I worked here in my teens and twenties, but because it is built on sacred ground. Its foundations occupy the site where in 1763 a band of vigilantes murdered the last indigenous people to inhabit Lancaster County when the land was still a wilderness. Those same foundations later served to incarcerate African Americans fleeing slavery. Thus is the Fulton implicated in the two great crimes on which this nation was built. That a working theater should function for nearly two centuries in such a place strikes me as both absurd and acutely poignant. It’s as if someone had deliberately tried to create a metaphor for the complicated realities of American culture.

The nineteenth-century Shakespearean actor E. L. Davenport called the Fulton “the most beautiful temple of art in the United States,” and it remains one of the most irresistible of American theaters—a crimson and gold wedding cake of a place inside, outside a stately monument to Lancaster-born Robert Fulton, who tinkered with submarines in the Seine and built America’s first commercially viable steamship. Here is a building where America invented itself—where actors shed their European roots to create a genuinely American style of performance, where audiences confronted an image of themselves and who they might become, where a nation wrote and rewrote its history. This singular space resonates in ways no other American theater does. Hence this book, a small gesture of gratitude to a place that has given so much to so many.