Читать книгу Staging Ground - Leslie Stainton - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

MR. HAGER BUILDS A HALL: 1852

In his 1827 preface to Cromwell, Victor Hugo wrote that the place where a catastrophe occurs becomes forever afterward a “silent character” in a tragic tale. It is doubtful Christopher Hager thought much about tragedy or character as he ordered workmen to begin dismantling Lancaster’s old jail and workhouse in the summer of 1852, although he did hire a sometime church architect to design the hall he intended to build on the site—an unconscious nod, perhaps, to the gravity of his undertaking.

Hager’s portrait hangs upstairs in the offices of today’s Fulton Theatre, and I’ve studied it more than once, trying to see in the Hapsburg nose and pinched mouth the template for the Hager men I have known in my own lifetime: Christopher’s great-grandson Nat, who did much to save the Fulton from the wrecking ball in the 1960s, and Nat’s son Chris, my old college classmate and friend, who has done his share of backstage work at the Fulton and is the seventh generation of Hager to have served on the vestry of Trinity Lutheran Church. The family’s long sojourn in Lancaster began on September 26, 1764, nine months after the slaughter of the Conestogas, when young Stoffel Heger, a butcher from Hessen-Darmstadt, arrived in the city after crossing the Atlantic with a shipload of fellow immigrants and swearing allegiance to King George the Second. Fourteen years later, Heger—by then Christopher Hager—signed a second oath, renouncing his allegiance to the king and swearing loyalty to the new and independent Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The butcher Hager had three successive wives and eight children, including a boy named Christopher, born in 1800 and baptized, like his siblings, at Trinity Lutheran Church. This second Christopher Hager, the eventual builder of Fulton Hall, was eighteen when his father died and was buried in a small yard adjoining the stately brick sanctuary where two centuries later members of the Hager family would continue to worship. (Not long ago I watched my friend Chris play Jesus in a vacation Bible school pageant at Trinity Lutheran.)

In 1821, three years after his father’s death, Christopher Hager Jr. opened a store near Lancaster’s market and jail and began selling dry goods, queensware, and groceries. His prices were fair, and his buying trips to Philadelphia yielded bargains: a shipment of coffee drenched but not damaged by seawater, a hundred barrels of molasses. Business bloomed. He began extending credit to his customers, and farmers started to invest their cash surpluses with him, making Hager a banker as well as a merchant. He issued loans to friends and family, expanded his store, bought real estate, and perfected a baroque signature not unlike John Hancock’s. In time Hager became president of the Farmers National Bank, president of a volunteer fire company, county treasurer, a manager of the city gas company, a trustee of the local college, an officer in the Lancaster County Colonization Society, and a founder and early manager of the Conestoga Cotton Mills, Lancaster’s midcentury leap into the Industrial Revolution.

Hager wore his sideburns low and his dark hair swept forward onto his face. His nose was long and pronounced, his eyes brown, and when he had his portrait painted shortly after his wedding to the former Catherine Sener, he donned a creamy yellow waistcoat and black jacket. Over the course of their forty-six-year marriage, Christopher and Catherine Hager had ten children, three of whom went into business with their father. When I was a kid, Christopher’s great-grandson Nat was still running Hager’s Department Store.

Christopher Hager grew up in a subsistence culture and helped create an urban one. The Lancaster of his youth—capital of Pennsylvania from 1789 to 1812, and briefly a candidate for the nation’s capital—was a mostly agrarian community whose six thousand inhabitants, half of them German, half English, lived in one- and two-story brick homes on unpaved streets shaded by trees and watered by tributaries of the Conestoga River. In its size and scope, the place was almost medieval. The chief industry in the surrounding county was flour milling. Lancaster itself had a market and courthouse, a dozen or so churches, and at least as many taverns, where itinerant players sometimes put on shows. (In the year of Hager’s birth, a Pennsylvania actor named John Durang performed an “Indian War and Scalp Dance” for the state governor at the Sign of the White Horse, on King Street, a stone’s throw from the workhouse where the Conestogas perished.)

By the time Hager reached middle age, the town of Lancaster had become a city with a population of more than twelve thousand and what one resident remembered as “nothing but bustle and confusion, arrivals and departures of cars, stages, carriages, hacks, drays, and wheelbarrows, with hundreds of people, and thousands of tons of merchandise.” Paved streets, lit by gas, were home to multistory banks, stores, churches, a telegraph office, and the city’s first lager brewery. Rail lines and a new canal, plied by a steamboat called the Conestoga, linked the inland city to Philadelphia and Baltimore. There was talk of building a bigger courthouse and a new jail. The old colonial prison on Prince Street had run out of space, and besides, the citizens of Lancaster were tired of having inmates in their midst—criminals petty and grave, debtors, drunks, Negroes fleeing slavery. Children on their way to school used to see prisoners gazing forlornly from the building’s grated windows, and everyone agreed that was too much. So work began on a new and much larger jail on the city’s east end.

The new facility, a massive sandstone fortress that looked like a castle, opened in the fall of 1851, and the following spring, officials put Lancaster’s now-vacant “old Bastile” up for sale. Christopher Hager submitted the highest bid—$8,400, roughly $250,000 in 2013 currency. Within a month of purchasing the prison complex, he announced his intention to erect a four-story public hall in its stead, to be used for meetings, conventions, lectures, exhibitions, concerts, and plays—a secular place of congregation for the residents of the city whose prosperity was so vital to his and his family’s interests. He also disclosed the name of the building he intended to construct on the site of the old prison and workhouse: Fulton Hall, in honor of the late Robert Fulton, the Lancaster County–born engineer and inventor whose inventions were fueling Hager’s century.

In early American villages, the meetinghouse “determined the character and limits of the community,” Lewis Mumford writes in his early twentieth-century survey of American architecture, Sticks and Stones. “Around the meeting-house the rest of the community crystallized in a definite pattern, tight and homogeneous.” As the American village morphed into a city, its need to retain a sense of community grew. Town halls—the nineteenth-century equivalent of the colonial meetinghouse—were crucial to that effort.

Although he left no public explanation of his reasons for wanting to build Fulton Hall, the canny Christopher Hager seems to have grasped instinctively what Mumford, citing Plato’s Republic, teaches in his book: that “an intelligent and socialized community will continue to grow only as long as it can remain a unit and keep up its common institutions. Beyond that point growth must cease, or the community will disintegrate and cease to be an organic thing.” Hager saw that his expanding city required a new gathering place where members of the community could forge bonds that were neither religious nor legal but rather social, cultural, and political, and that, furthermore, such a building could, in its very appearance and configuration, be an instructive and edifying force.

Enter Samuel Sloan of Philadelphia. Thirty-seven, brash and opportunistic, a quick learner who had begun his career as a carpenter and risen to architect, the man Hager chose to design Fulton Hall possessed no formal training but had what both men believed the profession required: taste, sensitivity, discrimination, and a vast fund of practical knowledge of the sort that defined so much of nineteenth-century American enterprise. Sloan understood masonry, joinery, carpentry, plastering, and painting; he knew why Grecian moldings were superior and that if you were to avoid lawsuits, you had to sign an airtight contract.

His models, like those of so many of his peers, were European—Palladio, Inigo Jones, Christopher Wren. When it came to style, Sloan preferred the Italianate. “Its great pliability of design, its facile adaptation to our wants and habits, together with its finished, elegant, and picturesque appearance, give it precedence over every other,” he explained in one of the numerous books and articles he published in an effort to educate American consumers. “It speaks of the inhabitant as a man of wealth, who wishes in a quiet way to enjoy his wealth. It speaks of him as a person of educated and refined tastes, who can appreciate the beautiful both in art and nature.”

I can imagine Hager’s delight at seeing himself in just this light, a man of means and polish, a first-generation American who had reached the heights of civic leadership and could now extend his good taste to the community. It’s little wonder he and Sloan hit it off. (A year later, Hager would help hire Sloan to design an ornate new pulpit at Trinity Lutheran.) To the architect, Hager was an ideal client: a man of independent thought and strong opinion, one of those thrusting, inquisitive personalities who were reshaping the cultural life of the United States.

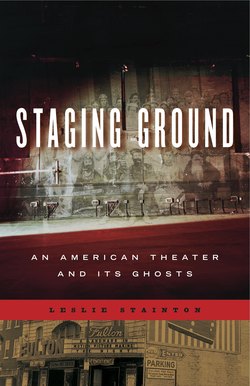

The two would first have talked about what Hager wanted: a multipurpose building flexible enough to accommodate the communal needs of a flourishing populace, a place of elegance, European in feel and look. Sloan would have drawn up floor plans, then elevations measured to scale, and finally a sketch showing the hall as it would look “in nature” from a given perspective. That drawing, now on display in the office of the Fulton’s managing director, reveals a square edifice whose milky façade rises in ever more delicate layers toward an airy cupola. Hager must have exulted when he first held the sketch in his hands. The front of Sloan’s hall is symmetrical but not monotonous, a pleasing blend of angles and arches, reason and sentiment. The heavy stone blocks of its first two floors give way to smooth plaster and a pitched roof with deep eaves held up by the Grecian cornices Sloan loved. The architect was designing for posterity: “We Americans are not ashamed that we have nothing now venerable in years,” he wrote in 1852, the year he designed Fulton Hall, “but we may fear that our descendants will have cause so to be, and have few buildings to point out, saying, this is the work of our fathers.”

Sloan and Hager agreed that the stage inside the hall would face east, as altars traditionally do, and that the side and back walls of the building would be constructed of economic brick. They also agreed to retain as much of the old prison complex as necessary to support the new structure. The architect knew stone to be the best foundation for any building, and the jail walls had already withstood nearly a century of wind, heat, rain, and ice without cracking, so he left whole stretches of James Webb’s masonry intact, including a two-story extension, with a vaulted double door, at the rear of the building on Water Street.

At the opposite end of the site, toward Prince Street, Sloan installed heavy log piers to help buttress his hall. The property itself was wildly uneven. Architect Dick Levengood, who took part in a late twentieth-century renovation of the Fulton Theatre, speaks of the “large-grade differential from the front of the building to the rear”—the site drops as much as fifteen feet from Prince Street to Water—and says the lot is “very challenging. It turns all the way around the corner, it drops both ways.” Webb had already figured out how to build on the site “so you don’t mess with it.”

Hager took out a permit to construct Fulton Hall in early May 1852, and work began at once. He told reporters the new building would be ready in four months. It was hot, and at least one worker was felled by sunstroke. Teenage boys hung around the construction site, hoping to catch sight of the dungeon, where a prisoner was said to have starved to death. (The rumor could well have been true: in a late eighteenth-century petition to the Lancaster court, prisoners inside the jail complained that they were fed “but one single pound of bread” a day, “which is scearsly suffitient to keep us alive.”)

Hager himself kept a close eye on the building and made frequent trips to Philadelphia to consult with Sloan. There were endless details to select: paint colors, window fastenings, plaster molds, ventilation, plumbing, light fixtures, doors. The press kept avid track of the project. “The new city hall, in Prince Street, is progressing finely,” the Lancaster Saturday Express noted in July. “Mr. Hager is pushing the work as rapidly as possible towards an early completion. It will be one of the finest public halls in the state.” Hager later calculated he spent $22,000—some $650,000 in 2013 dollars—on the venture.

Across America, people were doing just as he was, building shrines of culture festooned with muses and lyres in towns that a few years earlier had been little more than frontier outposts. The country was refining itself, as Sloan hoped it would. Part of that process was a newfound tolerance for the dramatic arts. William Penn and his Quaker peers had frowned on theater, and the first Continental Congress had banned it outright, but by 1850, major cities east of the Mississippi all had stages, and the suddenly popular art had spread to California, where men were digging for gold. Stock companies prospered. An American style of performance was emerging, raucous and physical. This had something to do with the freewheeling nature of the country itself, it seemed, with evangelical preachers who danced and barked and erupted in convulsions, with politicians who courted voters through bombast, and audiences addicted to sensation.

The whole enterprise had once smacked of the tawdry and louche, and itinerant companies—mostly English—hovered on the margins of respectable society. The city of Lancaster had shunned playacting until the Revolution, when a local brewer turned his beerhouse into a short-lived theater so that British soldiers held captive in the town could put on Shakespeare. It’s likely young Robert Fulton, who was fond of sketching the enemy in his midst, attended. But after the war, the chary town resumed its old ways. “There is no theater, no assemblies, no literary society, nor any other public entertainment, except an itinerant exhibition of wax works or a puppet show,” a visitor in 1810 grumbled. Taverns sometimes brought in theatricals and panoramas, and there were sporadic attempts in the 1830s and ’40s to open a genuine theater, but nothing stuck.

Not so in 1852. In addition to its nine banks, sixteen places of worship, fifty-seven common schools, and nine newspapers, Lancaster would soon enjoy a public hall. As the walls of Sloan’s brick-and-stone concoction rose, excitement grew. “The first floor room is intended for political meetings, county conventions, etc.,” the Examiner and Herald reported. “The second is to be fitted more elaborately and to be used for lectures and entertainments of a social nature. The third is to be occupied by societies.” By fall, the paper added brightly, “we may have the pleasure of hearing Jenny Lind in Fulton Hall.”

In September Hager opened the unfinished building briefly so that the local Odd Fellows, who had been struggling to build their own lodge, could hold a soirée. Covering the event, the pro-temperance Saturday Express issued the welcome news that Fulton Hall did not allow liquor on its premises. By early October, workers were putting the final touches on the new structure. That month, Lancaster’s city council repealed an 1846 ordinance requiring a tax on “plays, shows, theatrical entertainments and circus performances.” The pennywise Hager was surely pleased.

And then it was complete, Sloan’s buttery palace, brilliant in the autumn sun, ready for business. The young city had seen nothing like it. Squint, and you’d think you were standing before a cathedral. In place of a steeple there was a lightning rod, and the tympanum above the front entrance showed not heaven and hell but a glass orb wreathed in flowers, but still, Sloan had wrought a thing of beauty, a paean to European taste and American ambition.

It rained on opening night, and Lancaster’s streets turned to mud. Crowds came nonetheless, ladies in crinolines and shawls, men in tailcoats and gloves. Hager, his hair thinning, sideburns going gray, was there to greet them. He had distributed fifteen hundred free tickets, and nearly that number of people showed up. One by one, they ascended Sloan’s handsome staircase to the second-floor saloon (from the French salon), lit by three gas chandeliers and thirty-two wall jets, and took their seats on wooden benches facing a small platform at the far end of the room.

The main speaker of the evening, Judge Alexander Hayes, who had recently succeeded Hager as president of the Conestoga Cotton Mills, praised his colleague’s achievement and reminded listeners that cities across Europe had long ago recognized the need for theaters, gardens, promenades, orchestras, and galleries. Now, Hayes exclaimed, it was Lancaster’s turn, the desire for recreation following “long continued effort, as naturally as night follows day.” The local Philharmonic Society struck up a polka written expressly for the occasion and dedicated to Christopher Hager, and the crowd, roused by the brisk tune, burst into applause.

As I summon this enchanted evening I see a room bathed in yellow light and a mass of glowing faces. All of Lancaster has turned out, it appears—shopkeepers and haberdashers, ironmasters, gun makers, bankers, lawyers, teachers, women in curls and chignons, young men with tidy beards. Christopher Hager stands in their midst, eyes creased in merriment as he accepts the congratulations of his neighbors and friends. Off in a corner the stentorian Judge Hayes is holding forth about the genius loci of this hall, how it will “kindle the social affections, adding length as well as happiness to life.” That this was recently the site of the local jail and workhouse—and witness to a massacre whose notoriety persists—is momentarily forgotten.

Now the strains of Hager’s polka give way to the oom-pah-pah of a brass band, and I catch sight of a middle-aged woman swaying in time to the music. Fair-skinned and gray-eyed, she might be me. One foot taps gently against the floor. She wears a taffeta gown with a lace collar and long sleeves, and beneath it a corset and petticoats stiffened with whalebone, although she is not thinking now of the ocean life that gave rise to her fashionable silhouette. She seems oblivious to anything but her own enjoyment this night. Later she will scrawl a note in her diary—a great and attractive crowd filled Mr. Hager’s new hall, we stayed past 9:30—and in time she will buy a small volume in which to record her impressions of the plays she sees here.

Her boots are damp from the rain outside. When the band pauses, she can hear the thrum of water against the windowpanes. The sound pulls her briefly out of her reverie, and she thinks back to this afternoon, to the small leather case she received from the Daguerrian Gallery on Queen Street. The studio opened in May, but it was not until last week that she ventured to sit for her picture, curiosity finally conquering fear. The camera operator had put her head in a vise, and she’d sat for three minutes, unsmiling, while the exposure took. Opening the case this afternoon, she discovered a silvery image inside a gilt frame, and for the first time beheld her own likeness. I saw my face as I had never seen it before, she wrote in her diary, and strange thoughts flowed through my mind.

The proprietors of the gallery had promised her a “lifelike and enduring” portrait, but in fact she looked like a ghost. If she tilted the image in one direction or another, she found, her face vanished, and the effect was unsettling. In my estimation it is better to make the hearts of your friends the plates upon which to impress our pictures, than steel, brass or any inanimates, she wrote, and then closed the little case, vowing not to dwell further on the matter. But she couldn’t help herself. Dipping her pen back into the ink, she scribbled, My first picture! When will my last one be taken? Let the future answer.

Now, inside Mr. Hager’s hall, the band has resumed playing, and the bright present again quells the afternoon’s odd sensations. The woman in the taffeta gown turns with pleasure to the spectacle around her. The room is vast and smells of fresh paint; there is a tiny balcony at one end, and there are tall windows along each wall. Mr. Hager has pledged that this will be the site of so much she has dreamed of: dancing lessons, balls, lectures, fairs, concerts, prayer meetings, and of course plays, tales brought to life by performers who will travel hundreds of miles for her sake, so that she can come to this room, and sit in the shadows, and lose herself in their sorcery.

Thunder begins to rumble, and someone gasps, but Mr. Hager laughs and announces in a triumphant voice, “My friends, there is nothing to fear, nothing at all, for Mr. Sloan”—he points to the dapper man at his left—“Mr. Sloan has thought of everything, and we are quite safe tonight. Quite safe indeed.”

It is true. Should lightning strike, a man beside her whispers, it would hit not this building but the ingenious wrought-iron contraption first designed by Mr. Franklin, which sits on the roof and runs down the side of the hall, deep into the ground, carrying electricity with it. You are entirely safe, he assures her, and smiles.

She looks up at the ceiling and imagines the tall rod above it that guards her life and the lives of everyone around her. The rain continues to fall, but here in Fulton Hall everything is dry and warm, and although she knows better, she allows herself to believe that nothing can break the spell of this prodigious building, this temple of art, here in the center of the tranquil inland city she calls home.