Читать книгу Staging Ground - Leslie Stainton - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

HAUNTED

Late at night you feel them. Underneath the stage, in the long tunnel that stretches the length of the theater, the stone walls of the old prison ooze a cold sweat, and in the shadows you think you see shapes huddled under blankets, shivering. You tell yourself they’re only curtains piled in the corners, but even so they make you start, and you hurry upstairs.

Onstage, a single lightbulb on a metal stand sheds enough glow for you to make out the ropes and pipes hanging overhead, the canvas flats meant to be someone’s front porch, a one-sided automobile. Props from the night’s performance lie in a chalked grid on a table in the wings. On a lectern in the corner, the stage manager has left her prompt book open, each page annotated like a medical chart. Out in front in the dark are rows of empty red seats and the curving white edges of two balconies, and on the ceiling, peering down, a pair of plaster angels who’ve been holding their comic and tragic masks, respectively, for more than a century. Here too you sense you’re not alone.

Somewhere in the curlicues of the proscenium is the smudge of a bullet fired by Buffalo Bill. He’s standing beside you now, dressed in leather chaps and a fringed coat, smelling of prairie. Over there is Ethel Barrymore, running lines, and George M. Cohan, warbling a patriot song, cane in hand, feet thrumming, and here’s Bert Williams in blackface, cradling a tuba. Behind you Thaddeus Stevens slams his fist down on the podium and cries, “Abolition! Yes: abolish everything on the face of the earth but this Union; free every slave—slay every traitor—burn every rebel mansion.” Soldiers are upstairs drilling, and President James Buchanan is sitting downstage, lost in thought, and the voices of the slain and their survivors mingle in the high reaches of this space, beyond the pin rail, and suddenly you catch a whiff of scent as Sarah Bernhardt makes her way through the house, skirts sighing, on her way to the dressing room. She refuses to come in by the backstage door, unseen.

Hold still for a moment and feel the stream of time, feel your place in it. Outdoors the city is quiet. The market is locked tight, the nail salon next door is closed, the banks and restaurants empty. Over on Chestnut Street, at the spot where Abraham Lincoln addressed the citizens of this town on his way to his first inaugural, nothing stirs, and it’s equally silent at the site of the old railroad depot where his funeral train edged its way through weeping crowds four years later. The bars have issued their last calls, the mayor is asleep, and only the police station and the hospital where I was born in the middle of the twentieth century bristle with life. Gone are the taverns whose painted signs once lined the sidewalks, the White Swan and Cross Keys and Cat, gone is the brick courthouse in the center of town where Indians exchanged shells for the promise of peace and land. A tree shivers in the night air, a taxi idles.

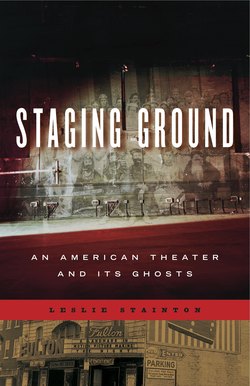

The pale white exterior of this theater is its own phantom. The marquee is dark; you can barely make out the word “Fulton” or the sculpted figure two stories up to whom it refers, a short man with a lantern jaw and a tumble of thick hair who’s doing his best to look Napoleonic in a cutaway coat and flowing cape, hand on his breast. He stands in a vaulted niche that looks as though it belongs above the entrance to a cathedral, and he gazes out on the streets where he played as a boy, more than once with British prisoners of war in a game he and his friends called Rebels and Tories. Eleven-year-old Robert Fulton, eventual inventor of submarines and steamboats, sketched these scenes, he and the other boys leaping across a rope to pummel the enemy.

I was eleven myself when I first set foot inside the Fulton Theatre in downtown Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Johnson was president; the headlines were full of body counts in Southeast Asia. At home, I watched The Monkees every week on TV and listened compulsively to Julie Andrews on my record player. I came to the Fulton for movies and the occasional concert. When a film bored me, I scooched down in one of the theater’s seats and shot my legs up in the air and bicycled. The place was dilapidated, paint peeling and carpets worn. There was talk of tearing it down to build a parking garage. Outside, a neon sign proclaimed, “A Landmark in Motion Picture Making!”

Inside, the spectral faces of Alan Bates and Julie Christie glimmered on the screen. As I watched their love blossom and then burn, I slipped from my own skin into theirs, glad to exchange the tedium of my junior high existence for their pain. I was just waking to the world. The cone of light trembling in the ether above me contained every future I might possibly want: the Austrian hills, a Dorset field, the pomp and circumstance of the Royal Ascot. If I could only reach up and nab a speck of it.

The room was dark, the furnishings shabby, the stage (for I knew there was one behind Bathsheba and Gabriel) a gray, impenetrable cave I longed to investigate. Soon afterward, watching my first plays on that stage, I was struck by how distant things became when they were real. Absent the giant screen we were genuinely little, I saw, but that was OK, because we belonged to a larger and quite beautiful cosmos. Moons flew in unannounced from the flies, summers burst into kaleidoscopic falls. You could see dust mites dancing in the tall black air and the shadows of strangers in the wings; clearly we were surrounded by all kinds of things visible and invisible.

By the time I turned thirteen I’d resolved to make a life for myself in the theater. I took acting lessons and memorized monologues about young women striving to understand themselves (Joan of Arc, Emily Webb). At a moment when I despaired of ever having a boyfriend for more than three consecutive days, I donned a crinoline to play Elizabeth Barrett Browning in a two-person show about love. One day I auditioned for a musical at the Fulton. I must have been sixteen. I wore a pink corduroy Betsey Johnson pantsuit I’d sewn expressly for the occasion. Shortly after I began to sing I realized that I was also, at the same time, standing to my own left and back a little ways, watching myself sing. It’s the only out-of-body experience I’ve ever had. I remember nothing else about the event, except that I didn’t get the part.

Two years after that audition I went back to the Fulton to work as an apprentice in a summer equity company at $15 a week. We opened four shows in a month and ran them in rep for another month. I sang in the chorus of an Amish musical, ran lights for The Crucible, scrounged props for Tobacco Road, and spent weeks building eighteenth-century hoopskirts and vests for a revival of Royall Tyler’s The Contrast, a comedy about pure-hearted Americans and foppish Brits. Tyler’s play made its debut in 1787—nearly fifty years after real-life colonists put mortar to stone to build what would eventually become the foundations of the Fulton Theatre, and more than twenty years after a group of Indians died inside the confines of those stone walls.

I spent whole days and nights threading plastic stays into muslin corsets and jamming yards of taffeta into bodices no bigger than my neck. Ronni, the costume designer, smoked long, filter-tipped cigarettes and used a ripper to stir powdered cream into the tall cups of coffee she sipped all day long. Several months pregnant, she’d come down from New York for the summer to run the shop with her sister Joanie and a woman named Poof, who cut patterns. We all had what we called theater-gray complexions.

The costume shop stood down the street from the Fulton, in an old warehouse with the words “Mack, the Coffee Man” painted in black letters on its side wall. A pair of picture windows opened at street level onto our chaotic interior, and I often wondered what passersby thought went on inside. We were in a slightly seedy part of town. A private bar stood halfway between the costume shop and the theater, and at night you could see glimmers of fluorescent light behind the bar’s shuttered windows. To this day, when I hear the word “speakeasy” I think of that building. One morning a few years after our summer rep season, a costume designer spotted a shoe sticking out of the garbage skip next to the Mack building and tried to grab it for her shop but found it was attached to a foot. A homeless man had climbed into the dumpster the night before and died.

Things like this might explain why my mother once told me there were two careers she preferred I not pursue: funeral direction and the theater.

Theater was all I wanted to do, even if it meant subsisting on coffee and Tab from the neighborhood diner for days on end in order to get the show up on time, a feat we barely achieved with The Contrast. By 7:30 P.M. on opening night, I was still trying to finish a waistcoat for an actor who was due to go onstage at approximately 8:15. The coat was a deep blue ribbed silk, verging on plum, with huge cuffs and fluttering tails, and the actor was Michael Lewis, the misanthropic son of Sinclair. All summer long, Lewis fils had sat in his tiny dressing room sulking when he wasn’t smoking Tiparillos and complaining about something—the building, the pay, his fellow actors, the rehearsal schedule, us. He bristled if you so much as mentioned his dad, so we’d all learned not to say a word, but we knew who he was. It was right there in his playbill bio: “Mr. Lewis is the son of the late Nobel Prize–winning novelist Sinclair Lewis and the journalist and commentator Dorothy Thompson.” Just what those parents had done to make Michael the ogre he was, we couldn’t imagine. He was in his early forties, tall and stooped, with a long, curving nose that made me think of Captain Hook. He kept mostly to himself. Everyone knew he drank; in rehearsals you could sometimes detect the hazy aftermath of a round with the bottle.

That he was somehow wounded may have occasionally crossed my eighteen-year-old mind, but not that night as I stitched buttons into place and rushed over to the ironing board. Lewis, I knew, had been grumbling all day about our incompetence. He didn’t want to go onstage in a blouse, he wanted the waistcoat, and what in God’s name had we been doing all summer for it to come to this. I remember my frenzy, the uncomfortably pregnant Ronni urging me on, Joanie cheering as I pumped the last shot of steam into the coat and bounded out the door. The two sisters physically pushed me off on a hundred-yard sprint from our shop to the theater, shouting go, go, go. I tore down the street, past the speakeasy and the bums, the silver diner glistening in the dusk, onto the sidewalk and through the back door of the Fulton into the greenroom where Lewis was pacing. The red of his fury bled through his makeup. I threw the coat over his shoulders, yanked his arms through the sleeves, adjusted the front while he fiddled with the lace jabot at his neck, and then he was gone, upstairs and onstage, not a second to spare. I could hear applause through the ceiling, the creaking of the old floorboards as the son of the author of Main Street and Babbitt made his entrance that evening in one of the first American plays ever produced.

Within a year Michael Lewis was dead. Forty-four years old, he left a daughter and two sons, a wife and an ex-wife. The obituaries didn’t give the cause of death, but we could all guess, right or wrong, and anyway it didn’t seem right that someone so mean could survive for long. By then my own life had spun off in untoward directions. I’d quit the Christian theater group I’d joined in high school and taken up with a married set designer who seduced me in my college theater. I thought it a fitting location, given my passions. I look back now and see that I craved drama so desperately I didn’t mind wrecking lives in order to get it.

When I go back to the Fulton today, among the ghosts I find is the specter of my adolescent self. She and Michael Lewis have more in common than I would have imagined back then. Having now outstripped him in years, I recognize some of the devil that gnawed at him: the compromises of middle age, the burdens of family, the urge to secure your place in a country that disappoints as often as it inspires. Sinclair Lewis called America “the most contradictory, the most depressing, the most stirring, of any land in the world today.” Perhaps Michael Lewis shared that view. Perhaps as he stormed onto the Fulton stage in his silk waistcoat that long-ago August night he was invoking his father’s spirit.

We called our season the American Heritage Festival; exactly what that meant I couldn’t have said. It made me squirm whenever I heard John Proctor defend his integrity that summer. Week after week I sat offstage listening to him, my fingers on the light board, waiting for the cue to illuminate his desperate face. “My name!” he’d cry. “My name!” I pushed the levers up. What had provoked the madness of Salem, I wondered, never mind the madness that prompted Arthur Miller to write those lines? One night toward the end of our season, Richard Nixon resigned. The audience that evening was small, and I hurried home after the show to catch the real theater on my parents’ TV. The Vietnam War was raging; that year in college I’d read Arthur Kopit’s Indians and for the first time been urged to consider the connections between what we were doing in Asia and what we’d done on our own frontier.

I was too fixed on the future to realize a portion of that frontier lay under my feet every time I walked onto the Fulton stage. Scrambling up onto the pin rail to hang lights, I was a sailor charting the swells of my own possibility. Occasionally I went downstairs into the storage tunnel below the auditorium to retrieve a lamp or gel. Inside the subterranean gloom I could see the log piers the first Fulton architect had installed to help hold up the place. They’d since been reinforced with concrete, but beyond them lay soft earth you could touch. I had no idea how long that soil had been there, probably centuries. Further off in the dark were the limestone walls that ran like a maze through the underbelly of the opera house. They were the old jail walls, I knew, and without them the theater would collapse. But I seldom thought more about their presence, about the American saga they’d helped beget. I hadn’t yet learned the pull of the backward gaze.

The notion of the theater as a memory machine dates back at least to the sixteenth century, when an Italian scholar named Giulio Camillo suggested using components of a stage and auditorium as mnemonic prompts. The metaphorical implications of his choice have beguiled theater people ever since. “We all know these buildings are haunted,” a director friend said to me when I told him about my obsession with the Fulton. Camillo was after personal as well as collective memory, and for me, of course, the Fulton holds both. The lamps I hauled up from the basement and helped string over the Salem courtroom where John Proctor repeatedly went on trial in the summer of 1974 belong to more than one narrative.

I’ve been told that cells from Julius Caesar still circulate in the world, that with each breath I draw I’m inhaling molecules from ancient Rome. If I keep going back to the Fulton, it’s to suck in the past, of which my own is just a fraction. A child sees little but herself until one day she wakes and discovers she occupies a sliver of chronology in a ticking universe. I’d spent most of my life dreaming of what was to come, but that summer I shifted my gaze by a degree, and I’ve been turning counterclockwise ever since. I see now that we belong equally to the dead and the living, that if you put your hand out and touch the cold stone walls of history you can feel the thrum of your predecessors, those dim beings who’ve faded into the earth. I know now that if you race down a street at dusk, carrying a silk waistcoat in your arms, you just might make it in time for their story to begin.