Читать книгу Cimarrón Pedagogies - Lidia Marte - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Seeds of the Book: Genesis and Motivations

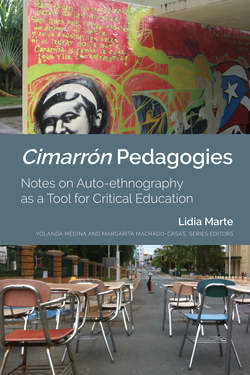

ОглавлениеThe book Cimarrón Pedagogies is a testimonial account and evaluation of the Critical Auto-ethnography methodology that I have used in my classroom as main resource to teach a variety of Anthropology and General Education college courses. This book offers description, evaluation and examples of how to use Auto-ethnography as main strategy for undergraduate research projects. Researching the ←3 | 4→ground of student’s everyday experiences through their personal perspectives, is a form of engaged pedagogy utilizing experiential, project-based and place-based assignments, as well as other experimental strategies (such as use of media, popular culture extra-curricular activities). Maybe the best way to summarize this approach is through the feminist phrase “the personal is political” (and vice versa); through an auto-ethnographic project this phrase is felt, not just pondered, researched and theorized. During the research process and the writing of their final reports, students not only learn how to generate their own research question and answered it, they also discover their own power to rename and narrate their own cultural histories. Through this testimony I wish to share the usefulness of auto-ethnography to help teachers–students research topics of significance to their lives and concerns, paying attention to the diverse composition of the classes, the type of institutions and the places where they are located. This pedagogical approach is a form of marronage, that help us create—at least in the classroom and for one semester—small liberated spaces, bridging the individual and the collective, private and public, past and present, the poetic and the political, and the local/global negotiations in our students’ lives.

My use of auto-ethnography in the classroom came about initially as an outcome of challenges with Internal Review Boards [IRBs] that regulates field research (permit for conducting research with human subjects required in the social sciences), particularly in my teaching of anthropology courses. The paperwork and complexity of this kind of application cannot be completed in one semester, and the process is challenging for undergraduate students (many of whom have never done any kind of research, nor heard about ethnography). Given this limitation, and because of my commitment to ethical research, I began assigning in my courses only auto-ethnographic field projects that they could complete in one semester, with a basic training in ethics. Since they worked with themselves as main center of their projects and collected only one oral history from a person known to them, they could get the research training and experience I wanted them to have. Students’ topics, research questions, their challenges and success in the completion of their auto-ethnographic projects were evidence that this approach was working. And, more important, they have produced original knowledge that inspired them to continue their education and their research projects or to continue documenting their family histories. The consistent harvest of good work that my students have produced over the years has revealed to me the power of auto-ethnographic methodologies, for anyone, to develop personally grounded projects with relevance to their local lives, without ignoring the macro-context and global webs that condition our lives. In the case of the Caribbean, such global interconnections (of ethno-historical accidents and imperial oppressions) dates back as far as the 16th century. ←4 | 5→I have been using this auto-ethnographic project-based approach since 2008, in Austin, TX, in New York City, and now in San Juan, Puerto Rico, with a wide range of diverse students and different general education courses, not only in anthropology. My students at the University of Puerto Rico, where I teach now, have shown me the other side of the Puerto Rican diaspora that I taught at CUNY-Brooklyn College; in both sides I have been witness to the power of auto-ethnography to help them understand where they are, and how they got to be there.

This book is also a closure harvest for me; there are many (and old) personal and professional motivations for this book, as will become clear later to the readers, but the actual written seed that launched the book as a viable project was planted through a paper that I presented at the conference African Diasporas Old and New, at the University of Texas at Austin (Marte 2014). That paper focused on these questions: Can we teach about the Caribbean without addressing Africa? and how do African Diaspora paradigms help us do this? This concern emerged from the challenges in my experience teaching Caribbean courses (in both anthropology and general education), in classrooms full of overt and subtle racism, and on the rewards of helping students acquire the basics of a racialization literacy. Beyond the paper, the audience for our panel was attentive and generous; after my presentation (with music soundtrack and interactive mappings) they gave me encouraging feedback, had many questions and a desire to know more about what it is, that I actually do, in the classroom. I hope that seed has grown now into a nice tree to answer some of their questions, and that it might give others new seeds for their teaching and for their own auto-ethnographic explorations.