Читать книгу Sometimes feelings are monsters - Lilli Höch-Corona - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Beginning

Let’s start with the story of how I became more involved with feelings and how I discovered the Gefühlsmonsters:

Even, or especially, as a mathematics teacher (during the years 1980–1994) I made an effort to create a pleasant climate in my classes. Special exercises helped to create a friendly learning atmosphere in which the students, as well as I as a person, found space.

One of my most moving lessons came from telling my class at the beginning of the lesson that I wasn’t feeling well because of an argument – and then bursting into tears in front of the class. Afterwards, we had a wonderful conversation about how difficult it often is to get along. Incredible, a conversation with the whole class (basic math class, 25 students between 17 and 22 years old) for 90 minutes! This was my first experience of how addressing feelings can develop into something very positive, touching – a genuine exchange.

Another time I heard from colleagues that one of my students had been beaten up and therefore missed a day. The next day I spoke to him about his black eye and to my surprise this student said after a while he felt that this kind of thing happened to him more often, that he always got into fights easily because he couldn’t control himself. It was obvious that he took responsibility for his actions without knowing what he could do differently. This conversation took place around 1982.

Subsequently, along with my students, I took part in assertiveness trainings. We learned from Jochen Dose, a police commissioner and anti-violence trainer, that it showed greater strength to control ones own behavior, and not to respond to a provocation, than to do what most did, namely to reply to an insult by entering into an exchange of words, ending in a fight (according to police research this is how it always starts).3

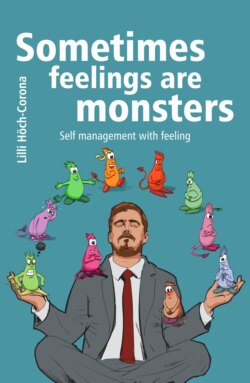

Later during my mediation training (1995) I learned that many conflicts arise because someone says or does something that they actually do not want to say or do. In one of my first mediation flyers I said: The fascinating thing about mediation for me is to experience how close our wonderful parts are next to the monster-like ones we show in the conflict. For my flyers4 my son gave me one of his monsters at my request, because I thought the difficult topic of conflict could do with a little humor. He had drawn the predecessors of our Gefühlsmonsters at a time when he was very interested in dinosaurs and enjoyed his various critters, which I then named monsters, referring to the monsters under the bed that all children probably experience at times. Later, when my son drew this monster with different feelings, I named it Gefühlsmonster (feeling monster).5 For me this matched the experiences from my work and the fact that this monster now showed different feelings. Only the patent attorney6, whom I later asked about the protection of our cards, made it clear to me that it was a brilliant name.

I had experienced often enough in myself and in my environment that we can show monster-like traits, and also how quickly these can change again into conciliatory, friendly ones when we feel heard and understood.

I have dealt with the topic of anger again and again in my mediation training sessions, conflict seminars, mediations, and team developments. Vera Birkenbihl gave me the image of the anger pot into which hormones drip until it overflows.7 In her lecture Be Angry More Effectively she says that we are born with a more or less strong disposition to get angry. You all know it, some of your friends may talk about how they’re quick to lose touch with others because they blow up so fast and then they’re sorry afterwards (those are the ones with the anger pot already almost full to begin with like my student, for example). Then there may be other friends who regret not having acted in a situation where they felt insulted. And of course there is the whole range of behaviors between these two extremes.

It was clear to me as a trainer that both groups need different learning processes. The beginning is the same for both: to become aware of what they feel as early as possible, before they act (or decide not to act). And then for the group of almost filled anger pots it is a matter of learning strategies that allow for conscious action, self-determined action, not externally determined action (exactly as the police trainer explained it). So acting instead of reacting. In the chain of principles (see page 18) for dealing with violence in public by Reinhard Kautz, the first thing is to perceive and take ones own feelings seriously. Many of us have forgotten this, often already in childhood through parents (who could not offer security in dealing with feelings, because of their own difficult experiences), in school, or later through misunderstood social conformity. It then requires a lot of support and practice to learn to perceive the signals of our own body again. I hope that you will find some ideas for this in this book.

To be aware of your body with its signals is just as important for the people with the barely filled anger pot. Here, after noticing the feelings, encouragement is needed to accept the feelings that arise and to feel free to do what feels right.

Chain of principles for social tensions, based on an idea by Reinhard Kautz and colleagues 8

Training your awareness:

Being able to detect tiny signs of escalation.

Taking feelings seriously:

To detect your own and other's feelings early.

Taking action early:

This prevents further escalation and thus further complications. De-escalating by asking questions and addressing the needs of the other person.

Acting versus reacting:

At the beginning of an escalation withdrawing is still possible (see illustration at the bottom of page 19). The longer the escalation continues the quicker it can come to paralysis, then there are less possibilities for constructive action.

Don’t provoke:

At a moderately advanced point of escalation each provocation is risky and can lead to us becoming part of the conflict.

Paying attention to distance:

Avoiding to get close to angry people. No touching of infuriated persons, not even direct criticism in this state.

Blocking:

Speed is a necessity. When someone doesn’t follow directions, when people around you insult each other, quick action is helpful.

To withdraw:

Withdrawal from further escalation might be necessary by taking a break to come up with a different strategy or deciding to break off the conversation.

Establish publicity:

When a challenging situation can’t be stopped it helps to involve bystanders or by addressing it publicly.

Illustration 1: Progression of escalation and possibilities to exit it

3 Now there are Confrontational Social and Competence Trainings (KSK®) which have been further developed from these initial experiences. Further tips on preventive anti-violence training in the appendix at the Internet pages

4 First mediation flyers see appendix

5 More about the history of the Gefühlsmonsters in the video Gefühlsmonsters – The Beginning(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDhn30eLvHg)

6 Many thanks to Mr. Hengelhaupt from Berlin!

7 Vera Birkenbihl: Der Birkenbihl-Powertag, mvg paperback 1998, p. 121ff, or DVD Effektiver ärgern

8 Chief Inspector Reinhard Kautz was awarded the Federal Cross of Merit in 1999 for his work in violence and crime prevention. The principle chain was the central core of his seminars; I got to know it in 2004 and have used it myself in my seminars ever since. Texts by me, graphics by Christian Corona