Читать книгу Beyond Mile Zero - Lily Gontard - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Travelling from the “lower forty-eight” states to Alaska, or from southern Canada to the Yukon and Northwest Territories, is a journey that most people do on the Alaska Highway. Sure, you can take the Alaska Marine Highway ferry along the West Coast to Skagway or Haines, Alaska, or the Cassiar Highway through British Columbia, but eventually, you’ll end up on this historic road.

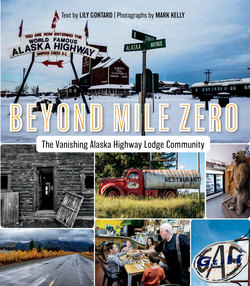

Alaska Highway lodges, such as Double “G” Service, pictured, have traditionally offered fuel, food, accommodation and most importantly, tire-repair services.

In the 1990s, Mark Kelly and I were both in our twenties when we moved (not together) to the North, and we each drove the Alaska Highway. My trip was made memorable by the first time I saw bison near Liard Hot Springs Provincial Park, and by the fact that the windshield of the van I was travelling in was totally shattered by a rock that flew out of a dump truck just west of Teslin, Yukon.

Mark’s first journey up the Alaska Highway was for a canoe trip on the Dease River. Years later, he transported his life from Squamish, British Columbia, to the Yukon and strapped to the roof of the truck was the same canoe he took on the Dease trip. In 2004, Liard Hot Springs Provincial Park became the background for that fateful moment when Mark fell in love with his future wife, Brooke, as they watched the northern lights wash in waves through a winter sky.

For the most part, Alaska Highway lodge owners are a welcoming lot. Depending how long you stick around, you might get lucky and hear a tale or two.

In the 1990s, fuel along the Alaska Highway was more expensive than in Edmonton or Dawson Creek, and both Mark and I travelled with a twenty-litre jerry can strapped to the roof racks of our respective vehicles. We both stopped for fuel only when necessary, and sometimes we’d stop at one of the lodges for a meal or coffee and a slice of pie. We share memories of the gas jockeys, wait staff and cashiers slightly tinged with a crustiness, and it’s no wonder the service was less than enthusiastic: the 1990s saw the decline of the lodge community, after the heyday of the early 1980s.

The seed for Beyond Mile Zero was planted in late summer of 2011. Mark and Brooke’s son, Seth, was born in July of that year, and shortly after his birth, the trio drove to Calgary to visit family. As parents know, a road trip with a newborn means frequent stops, and these occurred conveniently at abandoned lodges. While Brooke fed Seth, Mark would busy himself by taking photographs. It was Brooke who first suggested Mark do a photo essay on the changing highway lodge culture. Three years later, Mark asked me for advice about what to do with the growing collection of photos he’d taken of abandoned Alaska Highway lodges. We met for coffee, and I said his photos would make a great book. But first, I thought I’d pitch a photo essay to Geist. That’s how the feature “The Vanishing Roadhouse” ended up being published in Issue 100 in 2016.

Initially, the project centred around the abandoned lodges, the “fossils” of the highway lodge community: abandoned garages, piles of old tires, broken windows and peeling wallpaper. As we met more and more people who lived and worked along the highway, however, the story of the community emerged, and we began to uncover a hidden history.

The author, on a research road trip, stops for refreshment at Pine Valley Bakery and Lodge.

During our first research road trip in August 2015, Mark and I drove from Whitehorse, Yukon, to Delta Junction, Alaska, with a current issue of The Milepost—the travel bible for the route, published annually since 1949—and two lists of Alaska Highway lodges from 1947 and 1948. We wanted to see which lodges were still around. We found that most of the lodges no longer existed, and that there were lodges on the highway that weren’t on the list. We expanded our scope.

Our first interview on that 2015 road trip was with Ben Zhu, who co-manages Kluane Park Inn (KPI) with his parents, Gary and Sue. The family are recent arrivals to the Yukon, and they’re obviously loving it. The Zhus moved from Vancouver to run a lodge in Haines Junction, a small remote community in the Yukon. They represented a new kind of lodge owner: city folk who’d moved to the country.

In the bar of the KPI (which is legendary for raucous parties and good times), we met Ollie and Helen Wirth, who owned Burwash Landing Resort for thirty-one years. Both were nostalgic about their years operating the lodge—recalling community events such as curling bonspiels, the mad rush of seventeen tour buses that would stop in for lunch—and expressed their disappointment that the new owner, the economic branch of Kluane First Nation, closed the lodge in 2013 instead of continuing the legacy. The lodge was opened in 1947 by the Jacquot brothers and, until 2013, was one of the longest continually operating lodges along the highway.

After talking with the Wirths, we knew there was more to the stories of the highway lodges than the day-to-day mechanics of running a business. People arrived at lodge ownership through direct or circuitous routes: the Porsilds from Denmark via the Canadian Arctic, Sid van der Meer from Holland via Alberta and the Scoby family from Michigan straight to Alaska. These people were intimately connected to the places where they lived, raised children, made friends, and succeeded and failed.

Mark and I started working together on this project in December 2014. And, including his trip in 2011, altogether, we took five road trips and drove 8,113 kilometres (5,041 miles). That’s nearly four times the length of the Alaska Highway. We conducted more than forty interviews and took more than five thousand photographs. We talked with lodge owners along the Alaska Highway, and we tracked down former lodge owners who had retired to Oregon and Fairbanks. So many of the original lodge owners have passed away, but we found their children who had grown up at the lodges, and they live in Georgia, British Columbia, and Yukon. We conducted interviews via email, telephone and Skype. We did all this at the same time as we worked our full-time “paying” jobs. We know there remains more to discover, but we tried to capture as much as we could.

Mark and I are interested in people’s stories. As a photographer, he is looking for the story that gives mood and composition to a photograph. As a writer, I am inspired by the stories of everyday life and a desire to interpret, shape and share them with others. The stories we heard propelled us constantly forward, pushing us to do one more photo shoot or one more interview, to make one more telephone call.

When we started our project, we had very few expectations, aside from eating homemade pie and other baked goods. We found far more than we anticipated. We met people who were willing to share their time with us and tell us about their lives. Lodge owners are an unusual bunch. Free spirits, they set up businesses, for the most part, under challenging circumstances in the middle of nowhere. The stories of how and why they arrived, stayed and left are varied and compelling.

Barbara Abbott runs Tundra Lodge and RV Park in Tok, Alaska. The RV park’s bar used to be Rita’s Roadhouse, which was moved from the east side of the village to its present location in the 1960s.

The people we met share common characteristics: they are mavericks, entrepreneurs; they are independent, creative. They all share an adventurous spirit and are resourceful in the way they address their challenges, solve problems and create a community. The people who first started the lodges were self-sufficient, pioneers in aviation, in outfitting, in tourism. The modern world of automation, instant communication and government legislation has obliterated the conditions that allowed those lodge owners to experiment—for example, learning how to fly a plane by purchasing one, starting the engine and taxying down the highway. These people are part of an era that we’ll not see again.

Help us grow the history

We know we didn’t include all the lodges and all the stories in this book, but we’re always looking for more. Contact us on our social media channels to tell us what you know about lodges that weren’t listed on the map in this book, or to share your stories and memories:

Facebook: BeyondMile0

Twitter: @BeyondMile0

Instagram: @BeyondMile0

Though officially the Alaska Highway starts at Mile 0, Dawson Creek, British Columbia, prior to its construction there was a pre-existing road between Dawson Creek and just north of Fort St. John, to Charlie Lake.

A Note on Measurements of Distance

When the Alaska Highway was built, both Canada and the United States used the imperial system for measurements (though a US gallon remained inexplicably larger than a Canadian one). After Canada adopted the White Paper on Metric Conversion in 1970, the country slowly began the switch to the metric system. But Canadians have never fully embraced the metric system and navigate using a comfortable middle ground: recipes, weight and height are most commonly measured in imperial, whereas distance and fuel are measured in metric.

Almost three quarters of the Alaska Highway (or “ALCAN Highway,” as it is often called) passes through Canada. In Canada, the mileposts and imperial distance signs on the Alaska Highway were removed in the late 1970s, replaced with distance signs and markers in kilometres. Lodges along the Alaska Highway have traditionally been identified by the milepost where they stand, and lodge owners and truckers commonly speak about distance in historic miles. For the sake of this tradition, distances in this book will be measured in miles.

Another tricky point about distances on the Alaska Highway is that originally this route was 1,422 miles long, but after years of roadwork, it has been straightened and shortened. Its current total length is an elastic number that hovers around 1,387 miles. At the Alaska-Yukon border, distance markers challenge the driver, as there is a 35-mile difference between the actual distance from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and the number on mileposts. Although the official end point is Mile 1422 Delta Junction, Alaska, the common misperception is that the end lies 96 miles farther northwest, at Fairbanks.

While reading this book, if you are able, suspend your belief in the superiority of the metric system and the simple power of dividing by ten, as well as even a need for accurate measurement. And, for those of you who have a hard time thinking in miles, just remember: 1 mile is equal to 1.6 kilometres.

The original Mile 0 milepost stands proudly in the middle of a major intersection in the centre of Dawson Creek, British Columbia.

Yukon Archives, Rolf and Margaret Hougen fonds. 2010/91, #1005. Photo by Rolf Hougen, 1946.