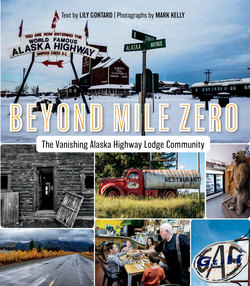

Читать книгу Beyond Mile Zero - Lily Gontard - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAbandoned Mile 351 Steamboat was burned down not long after this photo was taken.

Note: Italic typeface is used to indicate businesses not in operation at time of publication.

Mile 72 The Shepherd’s Inn

Mile 101 Blueberry

Mile 143 Pink Mountain Campsite and RV Park

Mile 143 Pink Mountain Motor Inn / Buffalo Inn

Mile 144 Sasquatch Crossing Lodge

Mile 147 Beatton River / Tucker Inn

Mile 162 Sikanni Chief

Mile 171 Mason Creek

Mile 175 Buckinghorse River Lodge

Mile 200 Trutch Lodge

Mile 233 Prophet River / Lum ’n’ Abner’s

Mile 275 Hilltop

Mile 295.5 Auto Service

Mile 351 Steamboat Mountain

Mile 363 Silver Tip Lodge

Mile 375 Tetsa River Lodge

Dawson Creek, British Columbia, is a city with a population of eleven thousand–plus that is just west of the border with the province of Alberta and 739 miles north of the city of Vancouver. Highway 49 approaches Dawson Creek from the east, and Highway 97 from the west, and just a few miles northwest of where these two highways meet, you’ll find Mile 0 of the Alaska Highway: the start of the route north.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the area around Dawson Creek was known as the Pouce Coupe Prairie, a name said to be derived from that of Chief Pouskapie (sometimes spelled Pooscapee) of the Beaver First Nation. The Beaver and Cree First Nations had been living in the region for centuries, with a constant rivalry between them and the Unjegah River (Peace River) dividing their territories. The prairie included present-day Pouce Coupe, Rolla and Dawson Creek. Just about every Dawson in Canada is named after George Mercer Dawson, the legendary surveyor, geologist and scientist from Nova Scotia.

Many of the entrepreneurs who started lodges along the Alaska Highway in the 1940s made use of the army and construction buildings left behind, such as the snow load–shedding Quonset hut.

Yukon Archives, Bloomstrand Family fonds, 98/73, #18.

The first Europeans found their way into the region in the late 1700s, and they were followed by the European fur traders. By 1891, the first settlers—members of the Thomas family (an anglicized version of “Tomas”), who were Métis—had begun farming. Then, in the late 1800s, came the large in-migration of non–First Nations people who were trying to take the extremely difficult overland route from Edmonton to the Klondike gold rush.

Bottom: Mile 106 in 1948—Alaska Highway lodge culture was born of an era of unpaved roads and slower, less fuel-efficient vehicles.

Yukon Archives, Elmer Harp Jr. 2006/2, #17.

In 1912, the Canadian government put parcels of land for homesteading for sale, prompting the growth of a non–First Nations population in the region around Dawson Creek. A post-war land offer was made to veteran British subjects, and that increased even more the settler population of the hamlet of Dawson Creek. When the Northern Alberta Railway line came to halt a few miles east of the hamlet in 1931, community members slowly moved to be closer to the depot. By 1936, the population was just over five hundred, and the village of Dawson Creek became incorporated. Then, in 1942, everything changed, as the US Army, very friendly-like, invaded the town. The construction of the Alaska Highway began. It wasn’t long, though, before people began to see the potential for the highway after the war: tourism, travel, trade. If people were travelling up that rough road into the North, they would need services.

Soon after the end of the war, public transportation companies such as Canadian Coachways and the British Yukon Navigation Company fulfilled the mutual needs of their own businesses and highway travellers by building lodges that provided accommodation, meals, fuel and vehicle repairs. (Fuel companies later jumped in on the action too.) In some cases, prospective lodge owners could lease or buy a property and pay back what they owed to the company for a few cents on every gallon of fuel sold.

The BYNC, which had been busing people up and down the highway between Whitehorse and Dawson Creek under contract with the military, constructed lodges to serve its customers and hired people to run these businesses. Mile 710 Rancheria Lodge, built in 1946, was one of those lodges, and the first managers, Bud and Doris Simpson, ended up taking over ownership of the lodge and running it for thirty years. There was anticipation that the highway would be opened to tourists imminently, but it remained closed for more than two more years; a military permit was still required for travel.

Finally, the highway opened to the public in 1948. To coincide with the anticipated influx of tourists, on February 16, 1948, the Canadian Department of Mines and Resources published a list of available accommodations and roadside facilities. There were some free campgrounds, but accommodations were scarce. Of the lodges included in that list, only Mile 710 Rancheria and Mile 533 Coal River still operate today (though the buildings at Coal River are not the originals, most of which were burned to the ground in a fire in 1969).

Mile 72 The Shepherd’s Inn

North of Fort St. John, at Mile 72, lies the Shepherd’s Inn—a modern-looking building, clad in vinyl siding. Behind it, homes are neatly arranged with a suggestion of a communal feeling. The gas pumps are new, the restaurant bright. On the menu is standard diner fare (burgers, Caesar salad), but it’s the homemade pies listed on a chalkboard on glass-fronted double-door fridges that are the standout items. Depending on the day and season, the selection could include berry medley, apple or pumpkin, or all three.

The air in the inn resounds with positivity, and the thirtysomething general manager, Ryan Hotston, and his octogenarian predecessor, Don Rutherford, are friendly and open in their approach to strangers. The non-denominational Shepherd’s Christian Society purchased the property in 1982 after the previous owners went bankrupt, hence the name “The Shepherd’s Inn.” These founders had been living at a religious community farther north and decided they needed to move to a property where they could be self-sufficient. They knew nothing about running a service industry business; they opened the inn with “a belief that God would take care of us,” says Don.

The Shepherd’s Inn “opened its doors with a bunch of rank amateurs to run the place, with no experience,” he says, his words lively with laughter. “All we had was a high hope that it was going to go—sometimes you have to make a sacrifice when you’re starting something.”

The Shepherd’s Inn is an unusual business along the Alaska Highway, as it’s run by a non-denominational religious society, the Shepherd’s Christian Society, and the business supports the adjacent community.

The on-grid community of about forty people lives on twelve hectares (thirty acres). It supplies its own water from three wells and grows its own food in greenhouses and gardens; unfortunately, that garden-fresh produce is used to feed the community and not the inn’s guests. The inn includes a restaurant, a “C-store” (convenience store) and a twenty-four-room motel.

“Our church building is behind the restaurant and everyone that lives here is part of the community,” says Ryan. “There’s a school, church, the business, and the community is private. Not everybody can live there.”

“There are about twenty people employed, mostly full-time,” says Ryan. The majority of the staff is from the community. “Some of the seniors that live here are part time, and we’re open all year round.”

Staffing has been a constant challenge, because the inn is twenty-five miles from Fort St. John, which is a long commute for someone earning minimum wage ($10.55 an hour in BC). The Shepherd’s Christian Society is committed to the long-term viability of its community and the business that supports it.

Don Rutherford (right) managed the Shepherd’s Inn with his wife, Dorothea. In 2016, Ryan Hotston (left) took over as the manager and is looking to the future of the business and the community it supports.

“The vision is to provide work for the members of the community—whether they be older or younger,” says Ryan. “I have five children and when they’re old enough, they’ll be working here.”

Ryan previously worked in the oil and gas industry and took over as the inn’s general manager in May 2016, though he’d been in training since the previous January. His predecessor, Don, an accountant, was involved in the Shepherd’s Inn from the very beginning: June 29, 1982. When Don became the general manager, his wife, Dorothea Mae, worked right alongside him.

Don is a consummate host; Ryan is friendly yet more reserved. Don smiles broadly with each statement he makes, and he takes the time to listen to questions. When he drifts off topic, he redirects his answers to the question that was originally asked. He was either born to welcome people to an establishment or he learned the skills of hosting during the decades he managed the inn.

“When things were quiet, people would come in and hug my wife,” Don says. “We never had an argument at work for thirty years. It was not quite so peaceful at home.”

“She was well liked,” Ryan adds. “She made sure to ask how you were doing. We still have people asking about both Don and Dorothea.” Running the business in the 1980s and 1990s was very different than in the 2000s. Don speaks of the friendship that his community and business developed with the locals, a predominantly First Nations community. Until 2015, the inn gave credit to regulars for gas and food, and in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a music school in the Shepherd’s Christian Society community and the inn hosted a weekly Friday night music-and-dinner event that ran for eleven years. The evening would start at five thirty and close down at a respectable nine o’clock at night.

“The first manager, his wife had a music school and they had a concert every night,” Don says. “People would call to ask, ‘Is the band playing tonight?’”

The inn didn’t sell alcohol and didn’t allow smoking in the restaurant.

“It was an illegal act [at that time], we didn’t care,” Don says. “One lady come in from Ontario with her daughter—when she found out she couldn’t have a cigarette with her pie, she was ready to hang me. I comped her pie.”

After the 1990s, the bus-tour and RV-caravan traffic slowed down, but the oil and gas industry boomed, and there was an increase in work crews travelling through the area. The recent downturn in the oil and gas industry is evident along the southern end of the Alaska Highway. From Dawson Creek to Buckinghorse River, lodges that became reliant on the industry have had a decline in business, and some have even closed completely.

The change in the inn’s customer base is reflected in the decision to convert the dining room—which is no longer needed to accommodate large groups—into a C-store.

“We’re still seeing some work crews, [but] 2016 is the slowest year we’ve had in a long time,” says Ryan. “Business as a whole is down about 35 percent because of change in the oil and gas industry.”

Don has a pragmatic way of looking at the unpredictability of a resource-based economy upon which the business has been partially dependant.

“Whenever it would go soft in the oil patch, we’d go down with it,” he says. “We’d cut back on our expenses. If you’re in business you have to be very aware of what’s going on around you, so you can match it and try to stay either even or ahead of it, but don’t get behind it, or down you go. It was pretty close some years.” He speaks as if imparting an important lesson to his successor.

Over the last thirty years, the Shepherd’s Inn has seen all kinds of travellers. In 2015 and 2016, there was an aged cyclist riding the length of the highway who has become a legend among the lodge owners.

“We had this one guy come through, he was riding his bike,” Don says. “He was over eighty years old. He sat at this table, he could hardly get his face over his breakfast bowl, he was that bent over from riding. His son was supporting him and he was riding to Vancouver. He stopped here overnight. He was quite a gentleman.”

Among the visitors is a whole subcategory of what Don calls “highway travellers in need.”

“In the past we’ve had to help a lot of people out—give out free rooms,” says Ryan. “In the last three weeks I’ve had about a dozen requests for free gas—people travelling the highway and running out of money.”

Sometimes people take advantage of the hosts’ generosity: one man asked Ryan to endorse a fraudulent cheque; a group of cyclists received a discount rate but then stole from the rooms. One time, a man’s car broke down in the parking lot; he promised to get it fixed but abandoned it instead. Don and Ryan can rattle off an endless list of minor irritations that they appear to accept as part of the price of doing business.

During 2015 and 2016, the society renovated the front of the motel, and there are plans to upgrade the rooms. “If business picks up, we want to upgrade our fuel system—get a canopy,” Ryan says. “Maybe start some more businesses for people in the community and go from there.”

A close community of people are dependent on the long-term viability of the Shepherd’s Inn, and the inn’s ability to adapt to the fluctuations and changes in clientele has served the business well. But it’s Don’s attitude toward the relationship between the business and the customer that offers insight into why the inn has grown and survived since the early 1980s. “You gotta know the pulse of your business,” he says, “in order for your customer to understand that pulse.”

Previous images: Korey Ollenberger and Lory Dille bought Pink Mountain Campsite and RV Park in 2000. The couple met in the mid-1990s when Lory was working as a cook at Mile 175 Buckinghorse River Lodge.

Previous images: Korey Ollenberger and Lory Dille also acquired Sikanni Chief (this page) in 2013. “[Pink Mountain] was really busy with the oil patch, the campers and everything,” says Lory. “We needed more space, plus there’s water wells [at Sikanni Chief] in the back, which benefited our trucking company.”

Mile 175 Buckinghorse River Lodge

The Buckinghorse River Bridge crosses over a narrow, whiskey-coloured body of water that travels west to east. Depending on the snowmelt, rainfall and time of year, it flows fast and high up the banks, or it’s the opposite. On a mowed grassy rise north of the bridge, on the west side of the highway, there are four signs: Bucking Horse River “Just Good Homestyle Food,” reads one, and below it, Buckinghorse River Lodge “Eat at the Buck” and Over 1,000 Truckers Can’t Be Wrong. To the right of an AFD cardlock sign, an automated fuelling depot that is accessed using a fuel card (like a credit card), is a For Sale notice.

Previous images: Vel and Howard Shannon have owned Buckinghorse River Lodge since the mid-1990s. Howard (pictured at bottom) swears that the lodge is only as popular as it is due to his wife’s cooking.

In 1999, Vel and Howard Shannon bought Mile 175 Buckinghorse River Lodge with Howard’s son, Lance, and his wife, Kim. Vel and Howard are now the sole proprietors. When they bought the lodge, it was in need of a lot of repairs. Although the Shannons have put a lot of time and money into renovations, Howard insists it’s the menu that really put the lodge on the map. “The lodge is as well known as it is because of Vel’s cooking,” Howard says. “It’s all her homemade recipes—that’s why people come back.” Over one thousand truckers can’t be wrong.

“For Sale” signs are a common sight along the Alaska Highway.

The Shannons took a roundabout route to lodge ownership. They lived in Fruitvale, British Columbia, where they ran a restaurant, and Howard had a welding, fabrication and forestry-related business. “That’s where I was born and raised, down there,” Howard says. “When they did the NAFTA thing, it totalled my business.”

The family moved to Fort St. John, where Howard got a job as a mechanical superintendent. Howard became frustrated by the lack of initiative at the company where he worked and took two weeks off to go hunting in the Buckinghorse area. Two months later, the Shannons were co-owners of a lodge. “I wasn’t looking for anything at the time,” Howard says. “It was a pretty good job, I was making eighty thousand a year. My dad thought I was absolutely out of my mind when we bought it.”

Some people might say that Howard is a person comfortable with taking risks: in the 1970s, he was a drag racer, building and racing his own cars. “I probably spent the price of three homes doing that,” Howard says. “I was an addicted drag racer—I spent almost all my waking hours doing that.” This addiction led to temporary separation from Vel. Once Howard gave up the cars, the couple reconciled and have been together ever since.

The Shannons have two sons who live on the property with them. In fact, of the ten to twelve people who work and live there, only one is not a family member. “We have a cook, she’s from Prince George. She’s been with us for twelve years.”

The dining room at Buckinghorse River Lodge is an old US Army barrack.

Howard describes Buckinghorse River Lodge as a seventeen-year reno project. The previous owners had the property for ten years, but it needed numerous upgrades. “The first thing we had to do was the water—two people couldn’t have a shower at the same time, and the water was this colour,” Howard says, pointing to the brown tabletop. “It’s a well system—it wasn’t treated or filtered or anything. Just raw water right out of the well.” Then there was the electrical. “Whoever was here had no idea what the hell they were doing,” Howard says. “They never fixed any outlets, just ran one extension cord to another one—I took fifteen or sixteen extension cords out in the first month.” Then the single-pane windows needed to be replaced. “When they built these old places they didn’t worry about the cold, they just put more wood on the fire.”

The Shannons are conscientious about conserving energy and have considered solar and wind power, but installing the infrastructure is too costly. As at most lodges along the highway, the power is supplied by two diesel generators. These are kept securely in steel shipping containers with fire walls built in at either end. The Shannons have good reason to house their generators in a near fortress-like building. Since 1999, they’ve had two generator fires; the first was in 2005. “That cost us just about half a million dollars in equipment, supplies, generators, fuel tanks, lawn mowers, quads,” Howard says. “There was a fifty-by-eighty-foot shop and I lost three generators.” They had been storing building supplies for renovations and lost all of those. “Doors, toilets, windows, sinks. We’ve never really recovered from that.” The second fire was in 2014, and that time the generator was brand new. Again, the family lost everything at a quarter-of-a-million-dollar cost. “The last fire I almost quit, but I just couldn’t.”

The Buckinghorse River Lodge’s history begins decades before the Shannons’ ownership (and generator troubles). The site of Buckinghorse River Lodge was a river crossing on the pack trail between Fort Nelson and Fort St. John, and in 1935, Wes Brown, a hunting-guide outfitter, and his family built a hunting lodge on the bank of the river. During the construction of the highway, the US Army used the site as a camp. The lodge at that time was on the east side of the highway, and to accommodate the fly-out hunting trips, an airstrip was built where the present-day parking lot now lies.

The lodge’s years on the east side of the highway were the busiest time in the business’s history. There was a restaurant, a liquor store, a gas station and rooms for rent. Wes moved what is now the lodge dining room, and an original US Army barracks with its coveted fir flooring, to the west side of the highway to use for his guiding business.

The Shannons have never guided any hunting trips out of their lodge, and they’ve had their busy and their slow times. As with many of their highway neighbours, the oil and gas industry contributed to the busy times. A camp was built on the east side of the highway in 2004, which operated for eleven years. “Everything slowed up here two years ago,” Howard says. “It’s been pretty quiet since. There’s virtually no activity in the oil field–related stuff—basically the operator just looks after the infrastructure.” The slowdown in the oil and gas sector is reflected in the Shannon’s business, as they figure they are doing 40 percent less than they used to.

Fire has been the death knell for many Alaska Highway lodges. Buckinghorse River Lodge has survived two generator fires since 2006 and the cost of the fires has taken a financial toll on Vel and Howard Shannon.

However, the decision to put the twenty-four-hectare (sixty-acre) property up for sale two years ago was not because of the slowdown in business but rather a completely unrelated event. In 2008, Vel and Howard were in a car accident in Prince George that left Vel with a broken back and five broken ribs. “Her internal organs aren’t where they are supposed to be,” Howard says. “She’s getting to the point where she needs more medical attention.” That attention is a two-and-a-half-hour drive south. Howard also admits that at sixty-eight years old, he’s getting to the age where the work of maintaining the lodge is not as easy for him as it once was.

The Shannons keep their business open year round, which is easy for them since they live on the premises. “It’s a lifestyle for us, too, basically,” Howard says. “My wife says it’s like camping out all the time.”

The Shannons have played host to several celebrities, notably a grizzly bear who’s graced the silver screen: Little Bart, the bear you may have seen in Into the Wild. (Little Bart is eight-foot-one-inch tall and should not be confused with Bart the Bear, who was nine foot six and appeared in Legends of the Fall. Both bears were trained by well-known Utah-based animal trainer Doug Seus.)

“They were filming in Alaska and were bringing him down.” When the trailer transporting the bear pulled into Buckinghorse River Lodge, it was having trouble with the shower system to keep the animal cool. “They are out there spraying the trailer and I started giving him shit. Then I saw the bear and said, ‘If he’s hot then you’d better cool him down.’” The handler let Howard touch the bear. “He was massive—that bear stood about damn near five feet at the shoulders.”

Once the Shannons sell the lodge, they’ll hit the road. Their final destination will be southern British Columbia, where they have family, but first, they’ll head north. The farthest north on the Alaska Highway that Vel and Howard have been is Mile 351 Steamboat. “We’ll stop at Liard, and I’ve always wanted to go to Skagway and take the train,” Howard says.

Mile 200 Trutch Lodge

You can’t see the Trutch Mountain section—the highway now skirts around it—but it lives on in early highway stories as a sometimes impassable incline, and a treacherous decline. The remains of Mile 200 Trutch Lodge exist deep in the woods, a sketch of the business that—from 1950 to 1963—was run by Don and Alene Peck. An old guidebook states the lodge was at Mile 201, whereas Ross Peck, son of Don and Alene, says it was at Mile 200. There was a highway maintenance camp at Mile 201, which is most likely what the guidebook was referring to.

This property inventory accompanied the bill of sale for Trutch Lodge, which Don and Alene Peck ran for thirteen years. The list includes everything from a chain hoist to hose clamps to a water barrel.

Photo courtesy of Ross Peck.

Ross, who is a retired guide outfitter and a rancher living in Hudson’s Hope, recalls that there were a few “Trutches” close to his parents’ lodge: “Somewhere in there, another lodge came into existence at Mile 195, which was also called Trutch and was run until it was displaced by the highway relocation.”

Don Peck was a trapper, guide and packer who had worked with legendary surveyor Knox McCusker. As the Royal BC Museum’s online Living Landscapes project explains, Knox McCusker was a lead in the logistics of constructing the Alaska Highway, but before that, he mapped out the Northwest Staging Route from Edmonton, Alberta, to Fairbanks, Alaska. The route was developed from 1940 to 1944 and was composed of airstrips that the United States used during World War II to transport combat aircraft to their Russian allies. Alene was a teacher in Charlie Lake and Fort St. John, and she learned accounting and bookkeeping working for the Royal Canadian Air Force during World War II. According to Ross, his father wanted to use the lodge as a base for his outfitting business and also have the year-round income from offering services on the Alaska Highway.

Previous images: There is barely a stick of timber left of Trutch Lodge, but during the time the Pecks ran the lodge there was a post office, restaurant, accommodation and garage, among other services.

Photos courtesy of Ross Peck.

Peck family lore tells that in 1949, Alene moved from Mile 47 Fort St. John, British Columbia, to become the first teacher in the new school at Mile 1016 Haines Junction, Yukon Territory. At the end of the school year, in the spring of 1950, Don drove up the Alaska Highway and collected Alene, and on the return trip, the couple stopped in Whitehorse to get married. They arrived as newlyweds at Mile 200 Trutch Lodge, which they’d purchased from Harry Noakes. Mile 200 sat on the site of a former highway camp, and when the Pecks took it over, the property consisted of a café and a garage. You could say that taking over the business was their honeymoon.

“In later years, they acquired some additional land in the vicinity, including some agricultural land down by the Minkaker River,” Ross says, “and an old gravel pit across the road.”

Ross was born in 1951 and has three younger siblings: sisters Patty and Kathy and brother Timber. All the children, except Kathy, worked at the lodge, and Ross first started pumping gas at four or five years old.

“Somewhere in there I got the idea of washing car windows and hanging around for a tip—an early squeegee kid,” Ross says. “That worked well until one day I tried it when it was a little too cold and left a layer of ice on a tourist’s front window. He wasn’t too pleased.”

When the Peck family lived at Trutch Lodge, the local population included people from a Northwest Highway Maintenance Establishment camp, the lodges and a Canadian National Telegraph camp. There were enough children in the area to warrant building a school in 1956, which Ross attended from grades one through seven.

Don and Alene worked side by side at the lodge. “When a cook quit you could see my father in the café kitchen,” Ross says, “and my mother would be out pumping gas when needed. Mother would cover in the café when needed—if the cook or waitress decided to run off with a truck driver.”

Although Don had many bushcraft skills, he was not inclined toward automobiles, so Trutch had a mechanic among the staff. Alene used her bookkeeping experience to manage the finances. The business grew, and aside from the original café and garage, Trutch Lodge ended up with a store, post office, pool hall, motel, staff quarters, the Pecks’ house and an airstrip. When their business was at its peak in the 1960s, they had about forty employees and the lodge was running twenty-four hours a day.