Читать книгу Beyond Mile Zero - Lily Gontard - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

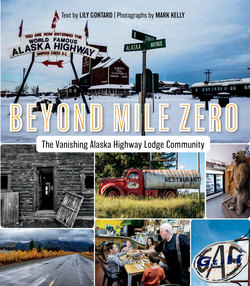

ОглавлениеCook’s Koidern, pictured, was operated by Jim and Dorothy Cook for decades and has been closed since 2015.

“till the heart stops beating / say the names”

Al Purdy

Silver Tip, Rocky Mountain, Swift River, Silver Dollar, Pink Mountain, Steamboat, Prophet River, Toad River, Krak-a-Krik—the names of lodges along the Alaska Highway read like a list of fairy tale place names. As you drive from Mile Zero at Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to the northern terminus at Mile 1,422 Delta Junction, Alaska, you can see many of these lodges—unofficial monuments to road travel—some of which evolved from the camps for the US Army crews who built the highway in 1942 or the camps that remained for road maintenance into the 1960s, and beyond.

However, sometimes you have to pull over and stop the car, open the door, and walk past the trees and shrubs that creep toward the soft shoulder and border the ditch. What hides from view is the slow degeneration of the lodge community that in its heyday was known as “the longest Main Street in North America.” Off the side of the highway, in the woods or in plain sight, will lie a log or frame structure partially demolished, with paint peeling from the walls, the vinyl seating and the wood panelling of sixties or seventies decor. Exterior and interior walls painted Caribbean blue or Smartie purple or seafoam green. Sloppy and expanding smears of garbage. Long gone are the Saturday night dances, the curling bonspiels that livened up the winter days, the miles-long drives to drop in for a cup of coffee. The busy sounds of an entrepreneurial community that began more than seventy years ago are now barely a hum on the landscape.

Building the Highway

In the early 1940s, most of the world was deeply entrenched in the manoeuvres of World War II. The eastern shores of North America were endangered by secretive German U-boats gliding stealthily through and by open navy battles on the Atlantic Ocean. From across the Pacific, Japan threatened from the west; it trounced its adversaries in the South Pacific and, in June 1942, overtook the Attu and Kiska Islands in the Aleutians, an Alaskan archipelago that gently curves across the Bering Sea toward Asia. The Americans supposed that this string of islands presented an easy route by which the Japanese might choose to invade Alaska and gain access to the continent.

Ultimately, it was the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, that set in motion one of the greatest highway construction challenges of the twentieth century. It was in this military theatre—North America facing adversaries on both coasts—that the Alaska Military Highway was built to facilitate the movement of troops to the undefended and sparsely populated northwestern frontier of the United States: Alaska. In March 1942, US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) troops from the “lower forty-eight” states started arriving in northern Canada and Alaska to build a winding pioneer road; it was surveyed from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, north through the Yukon Territory, and then northwest, ending in Big Delta at the confluence of the Tanana and Delta Rivers in Alaska.

In 1942, very few people lived along what would become the Alaska Highway corridor. The area of British Columbia from Dawson Creek to the Yukon border was sparsely populated, with a concentration of about five hundred in Dawson Creek. The Yukon counted just shy of five thousand people living within the territory’s borders, and Alaska had a population of seventy-four thousand, mostly found along the coast. Local people were hired for the construction, but the bulk of the work fell to a workforce that included ten thousand–plus American soldiers and six thousand civilians.

Mile 1061 Soldier’s Summit celebrates the end of the construction of the Alaska Highway in October 1942 when the last two sections were joined. However, the celebratory plaque is far from the location where the completion actually took place, which is closer to Mile 1202 Beaver Creek, Yukon.

“Alaska Highway” © Government of Canada, reproduced with permission of Library and Archives Canada (2016). Library and Archives Canada / Department of National Defence fonds / e010781534.

Until the construction of the Alaska Highway, the US Army did not allow racially segregated units to work alongside non-segregated units, and with the latter engaged in the war effort outside of the United States, the army was forced to change its policy if it wanted to complete this gargantuan project. The construction of the Alaska Highway became an equalizing event for the US Army as that country was heading toward the 1950s and 1960s, decades that would see the civil rights movement finally bring an end to government-sanctioned segregation policies. As John Virtue explains in his book The Black Soldiers Who Built the Alaska Highway, the construction of the highway would be the first time that US Army soldiers worked together no matter the colour of their skin. Despite collaborating on the project as a whole, the army units worked independently of one another on their respective sections of the highway, and there is much anecdotal evidence that segregated units were provided with inferior supplies and charged with developing the more difficult sections of the highway.

Mile 1306 Forty-Mile Lodge was built in the 1940s and was a going concern according to Jo Ann Henry (née Scoby), whose parents Ray and Mabel Scoby along with Clarence (“Red”) and Freida Post built and ran the lodge.

University of Alaska Fairbanks Archive, UAF-2006-131-30-2.

Initial construction of the highway was completed in late October 1942, when Private Alfred Jalufka of Kennedy, Texas, of the USACE 18th Regiment, driving a bulldozer northwest, and Corporal Refines Sims Jr., from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, of the USACE 97th (a segregated regiment), driving a bulldozer southeast from Alaska, met in the middle of a dense spruce forest near Beaver Creek, on the Canadian side of the border.

The original highway was called a “corduroy” road, referring to the way the road surface was constructed: tree trunks were laid down and covered with earth. This type of road made for a reverberating driving experience. However, when the route was finished, it was barely drivable in some sections and contractors working for the US Bureau of Public Roads had to regrade, reroute and redo the highway. Although the highway has been paved and chip-sealed from end to end, there are sections that continue to be improved—curves straightened, narrow sections widened, bulging frost heaves flattened out—even to this day.

The Alaska section of the highway was handed over to the Alaska Road Commission in 1944, but the US Army remained in charge of the Canadian part until April 1, 1946, when it was handed over to the Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE). Keeping the roadway in a drivable condition required constant maintenance, such as grading, repairing bridges and fixing the roadway after washouts, by the Northwest Highway Maintenance Establishment, which worked under the direction of the RCE.

When the US Army constructed the pioneer road, it also installed a long-distance pole-line communication system along the highway, but no power lines were added. This decision would have a big impact on highway lodges, as it would force them to rely on generators for power, and the cost of fuel would influence all pricing, from a cup of coffee to the price of a room. After World War II, Canadian National Telecommunications camps were established at the repeater stations to maintain the communications network along the highway. These camps, such as the one at Summit, British Columbia, became small communities consisting of their staff, the highway crews and their families.

Once initial construction of the highway was completed and the US Army moved out of the North, surveyors, heavy-equipment operators and mechanics were still needed, as were administrators, who were necessary to control the immense task of managing maintenance and care of the highway. This demand led to an increase in the number of women working along the highway, who during the construction phase had held only one of every twenty-four jobs, mostly in administrative support and service positions. This “one in twenty-four” number comes from a website created jointly by Yukon Tourism and Culture, Archives Canada and Canadian Heritage, called The Alaska Highway: A Yukon Perspective.

The First Lodges

Until the construction of the Alaska Highway, trains and riverboats were the primary modes of transportation in the Yukon and Alaska. There was a railway line from Skagway, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Yukon, and the Alaska Railroad owned several shorter railway lines that were eventually linked up. The White Pass and Yukon Route (WPYR) had a monopoly over the rail and river transportation from Skagway, Alaska, into the mineral-rich Yukon Territory. After the road was built, WPYR’s subsidiary, the British Yukon Navigation Company (BYNC), provided bus services between Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and Scottie Creek, Alaska. Over the years, this bus company built several lodges to accommodate its passengers: Fort Nelson Hotel and a lodge in Lower Post, both in British Columbia, and Dry Creek Lodge and Koidern Lodge in the Yukon Territory. An interpretive panel commemorating Mile 710 Rancheria Lodge as the first BYNC lodge construction to open on the highway between Watson Lake and Whitehorse, Yukon, in 1946, describes the variation of early accommodations: “Hastily converted army barrack buildings, stout two-story log structures and a framed wall tent for serving lunches.”

In the 1950s Lum ’n’ Abner’s was owned by Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Boyes.

Yukon Archives, Rolf and Margaret Hougen fonds, 2010/91, #1024. Photo by Rolf Hougen, 1946.

But even with transportation services in place and burgeoning infrastructure, the promise of allowing tourists free rein over the length of the former military highway didn’t come to fruition. Travellers still needed a permit and had to prove that they had necessary supplies for the journey. Then with the opening of the highway to public traffic in 1948, more lodges sprouted up to provide meals, services and accommodations to people working on and travelling along the highway.

Since the highway opened to the public, lodges have opened and closed, such as Mile 233 Lum ’n’ Abner’s and Mile 1095 Joe’s Airport, or lodges have opened, closed and then reopened, such as Mile 836.5 Johnson’s Crossing and Mile 1147 Pine Valley Lodge. The businesses were built for the convenience of highway travellers and sold or abandoned by their owners when times got tough or it was simply time to move on. According to The Milepost, in 1955, services were available every 25 miles. The 2016 edition, meanwhile, advised travellers to watch the fuel gauge, as services were found at times only every 100 to 150 miles.

Mile 717.5 Message Post Lodge was open until the late 1980s and according to The Milepost, the lodge offered “food, gas, a beer garden and souvenirs.”

A World of Visitors

By the time the Alaska Highway opened to the public, people were chomping at the bit to drive this road and explore the northwest reaches of North America. The Alaska Highway Heritage Project website notes that in 1948 tourists driving the highway numbered 18,600, and a mere three years later that number jumped to 50,000. The recent number, from Yukon Tourism border crossing statistics for 2015, may come as a surprise: 327,778. There’s no denying the attraction of driving the fabled road.

Back in the summer of 1943, when travel on the highway was only allowed for military purposes and residents, Mrs. Gertrude Tremblay Baskine from Toronto, Ontario, arrived in the Canadian commissioner’s office in Edmonton, Alberta, determined to acquire an Alaska Military Highway Permit. The permit was an elusive and mysterious piece of paper that would give Gertrude access to the ALCAN from Mile 0 in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to the end, at Mile 1,422 in Big Delta, Alaska. Why did she want to travel the highway? Her reason was simple: “It was impossible, naturally I had to try it.”

Previous images: The Alaska Military Highway was officially opened in November 1942. Though bus service was provided to military personnel and contractors throughout the 1940s, the highway was only opened to the public in 1948. Liard Lodge (pictured) was one of the first lodges constructed to accommodate bus traffic.

Yukon Archives, Rolf and Margaret Hougen fonds, 2010/91, (top) #463, (bottom) #1032. Photos by Rolf Hougen, 1946.

By this time in her career, Gertrude had achieved a number of things she’d set her mind to: she had a degree in social work from McGill University and a master’s from Columbia University, and was a graduate in letters from the Sorbonne University in Paris. She had worked as a social worker and a journalist. And in 1943, as a member of the Association of Canadian Clubs, she was travelling across Canada lecturing on the importance of women becoming involved in politics.

In her travel memoir Hitch-Hiking the Alaska Highway, Gertrude briefly mentions that Mr. Baskine fully supported her work (which turned out to be adventurous), but it’s also reasonable to guess that she was well placed in higher society by birth and/or by marriage (most likely both), and had access to influential people and the necessary funds to finance her journey. Travel in the North has always been expensive, and was even more so in the 1940s. To get her Alaska Military Highway Permit, Gertrude had to prove that she would not be a financial burden to the US Army.

Memorabilia from the Alaska Highway construction days can be found at lodges, RV parks and in peoples’ backyards from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction, Alaska.

In the summer of 1943, travel on the Alaska Highway was tightly controlled by the US Army, travel permits were inspected at military checkpoints, and only approved vehicles and people could travel the highway. It was seen as a virtually impossible act for a woman to travel the Alaska Military Highway—let alone on her own. (In fact, just after Gertrude left Dawson Creek, she heard that the army was going to ban women from travelling on the highway. So she put as much distance between herself and Dawson Creek as she could, as fast as she could.) But somehow, Gertrude left Edmonton with her permit in hand and set off to become the first and only woman to hitchhike the full length of the infamous roadway before it was opened to the public in 1948.

One year after her great adventure, Gertrude’s memoir was published. The word “hitchhiking” is a bit misleading: Gertrude was courteously shuttled by a variety of trucks, cars and Jeeps from one construction camp to the other “up the line.” Many people who worked on the construction of the highway had previously worked on the railway lines, and terminology from the railways permeated the highway lexicon. She even did a stint on horseback. She never actually put out her thumb, though she did get stuck in certain places for uncertain amounts of time, as hitchhikers so often do.

Gertrude travelled during wartime, and one of the restrictions on the publication of her memoir was that she wasn’t allowed to name the military people she met or the military posts where she stopped. However, she did mention the names of some construction and maintenance camps where she stayed: Mile 836.5 Johnson’s Crossing, near where the Teslin River flows out of Teslin Lake, and Mile 1094 Burwash Landing, on the shore of Kluane Lake. Both Yukon camps later became the sites of well-known highway lodges.

In 2017, seventy-four years after Gertrude Tremblay Baskine made her memorable journey, there is hardly any record of her expedition or even her writing career. The McGill University Archives holdings are limited, and deep in the Pickering/Ajax digital archive there is an announcement in the November 1943 issue of The Commando for a presentation on December 5 by Gertrude, but little else.

Lodge Culture Today

Knowledgeable and comforting, with the occasional cantankerous encounter, the Alaska Highway lodge community provides conversation and provisions in the middle of nowhere. The accommodations may be immaculately clean, at times slightly dated, the sheets a bit worn, but you can usually get a tire patched or a fuel tank filled. These days, most lodges have Wi-Fi; because cellphone service is still pretty much only available close to major cities, access to the World Wide Web is almost a necessity for the modern-day traveller. Often, you can tuck into a slice of homemade pie while posting to your social media accounts or checking email and road conditions.

Fresh baking and homestyle cooking are characteristic of the highway lodge culinary experience. At some point, cinnamon buns became the baked treat associated with the route, and lodge cooks bake these by the pan-load to satisfy the traveller’s appetite. North of Fort Nelson, British Columbia, at Mile 375 Tetsa River Lodge, Ben and Gail Andrews bake up to three hundred cinnamon buns a day. Tetsa cinnamon buns are known for a light texture, a sprinkling of spices and a sweet glaze with a slightly salty taste that will make you buy a second one.

Lodge owners, such as Olivier and Mylène Le Diuzet of Pine Valley Bakery and Lodge, put their own spin on what their lodge offers. The Le Diuzets, who are originally from France, include quintessentially French quiche and crepes in their menu.

North of Tetsa River Lodge, Donna Rogers, who owns Mile 533 Coal River Lodge & RV in British Columbia, with her husband, Brent, also bakes cinnamon buns. But from the shelves in her restaurant you can also buy homemade preserves and chocolates, and in 2003, she received a postcard extolling the virtues of her bumbleberry pie from a fan in the United States who’d driven the length of the Alaska Highway. “She wrote that it was the best bumbleberry pie she’d tasted,” Donna said.

Even though husband-and-wife teams have run lodges since the 1940s, official business partnerships pre-1980 consisted mostly of the husband and another man; the wife was not included on the paperwork. The labour at lodges was (and often continues to be) divided along traditional gender lines: the wife/woman takes care of the baking, cooking, cleaning and restaurant operations, while the husband/man runs the mechanical side of the operation, including the gas station and repair shop.

However, as is often the case in remote areas, traditional gender roles get thrown out the window when there’s no one to do the work or when one person happens to be good at and simply enjoys work that’s not traditionally associated with their gender. Siblings Ellen Davignon (née Porsild) and Aksel Porsild (whose parents, Bob and Elly, built Mile 836.5 Johnson’s Crossing Lodge in the late 1940s) say that after running the restaurant in the morning, Elly would take a Swede saw and cut kindling for one hour every afternoon, even though there were plenty of able-bodied men or boys around who could do that work. At Mile 436.5 Double “G” Service, Jack Gunness, a tall burl of a man serves up slices of his home-baked bread almost as big as dinner plates.

On a highway lodge menu, you’ll find a breakfast fry-up of eggs and a side of bacon, sausage or ham, with home baking, and soup made from scratch, along with deep-fried offerings and burgers. Vegetarians may be hard-pressed to find a tofu-, lentil- or bean-based dish, but there’s probably an iceberg lettuce salad dressed with pale chopped tomatoes. Whatever you choose from the menu, there’s always either water-weak or turpentine-strong coffee to wash it all down.

In fact, along this highway, where clean drinking water has at times been hard to come by, coffee was once the staple drink of lodge life. Gertrude Baskine recalled that in 1943, on the tables in the maintenance camp messes she visited, pots of coffee were replenished over and over, but no jug of water could be found. She felt she was being “weaned off drinking water” because she was told it was considered unsafe, since filtration and plumbing hadn’t been installed at the camps where she stayed.

When old-timers reminisce about the good old days, it’s doubtful that they are referring to the early days of snow clearing along the Alaska Highway.

Yukon Archives, Albert Charles Barnes, 89/99 #14.

At Mile 836.5, which had been a military construction camp, the US Army made several unsuccessful drilling attempts for water so that access to it wouldn’t be at the mercy of the freeze-up in winter. The Porsild family opened the Johnson’s Crossing Lodge on the site in 1949, and for many years afterwards, they hauled water in a tank on a trailer from Brook’s Brook maintenance camp six miles east down the highway. In the early 1950s, Bob Porsild installed a waterline from the river to the lodge, which was only used in the summer months. Water continued to be hauled from Brook’s Brook over the fall and winter for several years.

Luckily, in the twenty-first century, drinking water along the highway is not such a rare commodity as in 1943. The majority of lodges have wells. Mile 533 Coal River Lodge & RV is near the confluence of the Coal and Liard Rivers, and Donna Rogers is particularly proud of the taste of the water from her well. She serves a glass as if she were pouring from an expensive bottle of grand cru wine.

Three things are necessary for lodges to operate: fuel, water and human power. Anything that affects the availability of those, influences whether a lodge can operate for another month, season or year.

Today, when you drive the Alaska Highway, for every lodge that is open and offering hospitality and conversation, you’ll see one or two or three that are abandoned or have a For Sale sign posted on the property. If you look closely at the ground, you might see the outlines of old foundations. Sometimes, though, not even a trace remains: it could be that every hint of the lodge has disappeared, burned to the ground or been scavenged and carted away. The boom time of the highway lodges has passed, and what remains is a legend frayed on the edges.

Memory is reliant on perspective and experience, making history a malleable concept, and the histories of some Alaska Highway lodges are easier to unearth than others. Memoirs exist, and there are descendants and friends who recall stories, with or without embellishment. Meanwhile, other lodges are recorded solely as names in a single edition of a guidebook or map, the owners known or unknown, the stories evaporated into the landscape like the buildings that have been bulldozed or reclaimed by nature.

Early lodges were built using available materials such as the spindly spruce trees of the boreal forest.

Yukon Archives, Rolf and Margaret Hougen fonds, 2010/91, #1008. Photo by Rolf Hougen, 1946.

The Alaska Highway lodge community has evolved and devolved over time. Reliant on the highway traffic for its existence, the vitality of the community has been at the mercy of factors beyond its control, such as the “Black Monday” stock market crash of 1987 and the explosion of the American housing bubble of 2008, or the boom-and-bust nature of the oil and gas industry. The people who chose to open and/or operate highway lodges had to find within themselves the skills and resources to withstand outside forces, and continue to thrive, or not, whatever the case may have been. Beyond Mile Zero explores Alaska Highway lodges by sharing the unknown stories of a community that provides essential services along what remains a long and sometimes lonesome highway—a community that has been largely ignored by historians and journalists in favour of the hero-making effort that was the construction of the Alaska Highway.