Читать книгу Bleak Houses - Lisa Surridge - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

In “the adventure of the abbey grange” (1904), Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are called to investigate a murder in an upper-class home. Sir Eustace Brackenstall lies dead in his dining room, felled by a blow from his own poker. Lady Brackenstall, also injured, has a “terrible mark upon her brow” and two “vivid red spots” on her arm (SSH, 714). When Holmes and Watson arrive, she tells them what happened. The night before, she had been making a last tour of the house before bedtime. She entered the dining room, surprising three thieves who were coming in through the French windows. One man grabbed her by the wrist and throat; when she tried to scream, he struck her a “savage blow with his fist over the eye” (SSH, 715). When she came back to consciousness she was gagged and bound to a chair with the cord from the bell pull. Her husband rushed into the room with his cudgel in his hand. One of the thieves dealt Sir Eustace a deadly blow with the poker, whereupon Lady Brackenstall fainted again. When she came to, the thieves had collected up the silver and were helping themselves to the Brackenstalls’ best wine. They checked Lady Brackenstall’s bonds and fled through the French windows, taking the silver with them. She called the servants, who sent for the local police, who in turn called in Holmes. By the time Holmes arrives, the local police have identified the criminals as the “Lewisham gang of burglars”—“commonplace rogues,” as Watson describes them (SSH, 713; 715).

The private upper-class home shattered by lower-class poker-wielding ruffians; the protection of the wife by the husband; the wife as passive victim—“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange” seems a tissue of class-based assumptions about who commits crime, against whom, and how. But not so fast. Holmes notices that though three wine glasses are soiled, only one contains bees-wing, a crust that forms in fine wines after long storage. He also wonders how the criminals managed to use the bell pull to tie up Lady Brackenstall, since pulling on the rope would presumably rouse the servants. Although Holmes gets back on the train to London, these anomalies—meaningful only to those who understand fine wine and good servants—so obsess Holmes that he gets off the London train and goes back to Kent. There he minutely examines the window, the carpet, the chair, the rope, and the bell pull. “We have got our case,” he tells Watson, “one of the most remarkable in our collection” (SSH, 719). He tells Lady Brackenstall that her story is an absolute fabrication. He then sends a telegram to a ship’s captain working on the Adelaide-Southampton line.

Captain Croker arrives in Baker Street and relates a different story. He tells Holmes that he met and loved Mary Taylor (the future Lady Brackenstall) when he was first officer on the ship that brought her from Australia to England. When she married Sir Eustace, he accepted his loss, but he could not accept what he heard from her maid: that her husband abused her. According to Croker, there were no thieves, no intruders: the villain, he says, was Sir Eustace himself. Lady Brackenstall’s eye was blackened by her baronet husband, who was “for ever illtreating her” (SSH, 721). Croker himself killed Sir Eustace when he saw him “welt” her across the face with a stick (SSH, 725). The sailor then tied the wife to a chair to make her look innocent; poured the wine into the glasses to create the illusion of three thieves; threw the family silver in the pond to provide a motive for the crime; and disappeared until the telegram from Holmes summoned him to the Baker Street flat.

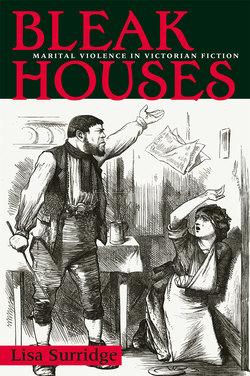

Like the first story, this one is heavily inflected by class, and it overturns all the assumptions of the first about where and how domestic violence occurs, and by whom and against whom it is committed. Holmes, Watson, and the reader are forced to reassess their assumptions surrounding domestic violence—assumptions that wife beating occurs in the kitchen rather than the dining room; that black eyes belong to the East End, not the east wing; and that commonplace rogues rather than baronets cudgel their wives. “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” then, is quintessentialy a text about reading narratives and signs of marital violence. With its multiple stories, multiple tellers (Lady Brackenstall, the maid, the sailor, the local police), and multiple interpreters (Holmes, Watson, the local police, the story’s reader), the text draws attention to how such narratives are produced, disseminated, and interpreted. It draws attention to the intrusion of the public gaze into the private sphere; to the body of the woman as a text to be deciphered by medical or legal experts (fig. 0.1); to the question of how a woman’s private loyalties may impact public narratives about or investigation into spousal assault; and to the role of the courts in the punishment of the assailant. As such, it foregrounds many of the key themes of this book.

Figure 0.1. Sidney Paget, “I Am the Wife of Sir Eustace Brackenstall,” illustration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” Strand Magazine (1904).

When I first started thinking about Victorians and marital violence, I was writing a footnote to an article on an entirely different subject. Like Holmes, I had a train to catch (although mine was metaphorical), and I almost walked away from the subject that now forms the focus of this study. At the time, I had not read the extensive wife-assault debates in the Victorian print media, and I was not aware that wife beating formed part of a web of Victorian issues surrounding marital power—coverture, married women’s property law, divorce law, conjugal rights—that I contemplated all the time. Like Holmes, I have learned new ways of reading, and in time my footnote became an article, and the article became this book. In the process, fictional scenes that I had previously thought of as peripheral came into a different focus for me. For example, I discovered that J. W. Kaye’s 1856 article “Outrages on Women,” written as he contemplated a parliamentary bill proposing flogging penalties for wife abuse, cites Bleak House (1852–53) as a text about how to deal with the problems of wife beating.1 In the midst of listing possible ways to alleviate marital violence—day care, parks, and improved housing being among his rather surprising suggestions—Kaye quotes at length the scene in which Esther and Mrs. Pardiggle visit the brick maker’s family. He sees Bleak House (which was serialized before and during the debates on the 1853 Act for the Better Prevention and Punishment of Aggravated Assaults upon Women and Children) as a paradigmatic example of public regulation of private domestic violence, of the public’s misreading or failing to read “the history of the black eye, or the bruised forehead, or the lacerated breast” (OW, 253). Until I read Kaye’s article, I had not perceived Dickens’s novel as part of the 1850s debate on wife-assault penalties, but rather had seen the black eye of the brick-maker’s wife as something of a sideline to the text’s main issues. This present study will, I hope, enhance the modern reader’s understanding of Victorian narratives of marital violence by suggesting their relationship to the Victorian debates on marital violence. At all times, I intend as far as possible to reinsert such texts into the cultural nexus from which they originated. The many bleak houses and black eyes in this book, then, are considered in their cultural moment as far as I can reconstruct it.

I turn back to Kaye for a moment because his article “Outrages on Women” contains one of the strongest Victorian statements about the prominence of wife beating in contemporary print culture. Kaye wrote in 1856 that “outrages upon women have of late years held a distressingly prominent position. It is no exaggeration to say, that scarcely a day passes that does not add one or more to the published cases of this description of offence” (OW, 233–34). To show how common such narratives had become in contemporary newspapers, Kaye cited a typical police report from the (London) Times:

WORSHIP STREET.—Charles Sloman, a surly-looking fellow, was charged with outrages upon his wife.

The wife, a decent-looking woman, who gave her evidence with manifest reluctance against her husband, said, she only wished to be parted from him; that the prisoner had lamed her with kicks, struck her in the face with his fist, and knocked her down. She had been married only eight years, but had been beaten and ill-used so many times, that she really could not say how often, but was seldom or never without black eyes and a bruised face.…

Mr. Hammill sentenced the prisoner to be committed to the House of Correction for six months, with hard labour, and at the expiration of that to find good bail for a further term of like duration. (OW, 234)

Such a narrative, Kaye observes, was not exceptional: wife abuse had become an “every-day story” in Victorian newspapers (OW, 234). As Kaye’s article attests, “marital oppression” or “wife beating” became the focus of considerable attention in nineteenth-century print culture.2 Police reports, newspaper and journal articles, cartoons, and political debates all testify to the urgency of this issue for Victorians. Battered women, asserted John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor in the Morning Chronicle in 1846, were dying “in protracted torture, from incessantly repeated brutality, without ever, except in the fewest and rarest instances, claiming the protection of law” (CW, 24:919). In 1853, Punch deplored

THAT the Tyrant Man should so long have been suffered, at the expense of a small sum, to wreak his malevolence on the Victim Woman; that the Brute, like a chartered ruffian, should have been empowered to beat, kick, and trample upon her, with indefinite, short of fatal, violence, for the consideration of about five pounds; … that even now the Wretch who may commit such outrages on a Female will incur no heavier penalty than a moderate imprisonment: might make foreigners imagine that our laws, in this regard, had either been enacted by a Parliament of BLUEBEARDS, or dictated by King Henry VIII. (Punch, 16 April 1853, 158)

Similarly, the Contemporary Review (1868) evoked “cases where a wife has suffered grievous bodily harm at the hands of a ruffianly husband, who, not considering ‘scourges and clubs’ sufficiently efficacious weapons, has beaten her with the poker or the fire-shovel” (IEL, 123). The theme was still powerful in 1874, when Punch featured a huge illustration entitled “Woman’s Wrongs,” depicting a man holding a poker, standing over and threatening his kneeling and injured wife (Punch, 30 May 1874, 227; fig. 0.2); in 1878, when Frances Power Cobbe deplored the prevalence of “Wife-Torture in England”; and in 1892, when Matilda Blake demanded “Are Women Protected?” and filled the Westminster Review’s pages with bloody narratives of wife battery while deploring the low sentences received by assailants.

In the ecclesiastical, divorce, criminal, and magistrates’ courts; in the Houses of Parliament; in domestic manuals, newspapers, journals, and petitions, Victorians debated how to prevent and punish wife assault. As these debates reveal, wife beating stood at the vortex of some of the most urgent issues of the period: marital coverture, divorce, domesticity, manliness, and women’s rights. Did the husband control his wife’s body? Her behavior? How should this authority be exercised? Was manliness compatible with violence? At what point did the wife’s rights as a person overrule the husband’s rights as domestic ruler? When and how should the law interfere in the relationship between husband and wife? Under what circumstances should the privacy of the home be sacrificed to protect the wife? In the courts, in Parliament, in newspapers, and—as I will argue—in their fiction, Victorians questioned the limits of male authority, the husband’s power to chastise, the definition of matrimonial cruelty, and the community’s role in regulating domestic violence.

This book examines Victorian novelists’ engagement with the issue of marital violence from 1828 to the end of the nineteenth century. My analysis starts in the years following the 1828 Offenses Against the Person Act, legislation that opened magistrates’ courts to abused working-class wives. This act was instituted by Robert Peel as part of his legal reforms, and was part of a general trend toward higher sentences for crimes against the person.3 Drafted in part because of popular concern about “disputes between man and wife,” the act extended summary jurisdiction to common assault and battery.4 Under the new act, abusive husbands could be tried and sentenced in magistrates’ courts without the need for a lengthy jury trial.5 Although the maximum sentence for assault under the act was relatively low (a fine of £5 or two months in prison), the remedy was quick and accessible. Soon after the act came into effect, the magistrates’ courts were flooded with abused wives.6 This shift toward the prosecution of minor assaults was in turn supported by Peel’s establishment of the London police force; after 1829, the police were available to arrest and prosecute abusive husbands (Doggett, 114).

Figure 0.2. “Woman’s Wrongs,” Punch 66 (1874): 227.

Social historians recognize 1828 as a key turning point for abused women because access to legal redress became cheaper and more accessible. I, in turn, am interested in the 1828 act’s impact on Victorian print culture—specifically, in how the act had the effect of bringing accounts of marital violence daily into the public eye. The 1828 act precipitated a significant cultural shift: newspapers like the Morning Chronicle and the Times, which habitually reported on police and judicial news, now reported on wife-assault cases on an almost daily basis. Not that newspapers had been free of wife murder and manslaughter cases prior to the act. On the contrary, newspapers in the late 1820s featured horrendous crimes of assault on wives and sexual partners, including the infamous “Red Barn Murder” of May 1827, in which William Corder killed his lover, Maria Marten, and buried her body in a shallow grave in the floor of the barn (Times, 8 August 1828, 2f, 3a–e; 9 August 1828, 3a–f). As Sir Peter Laurie remarked during the 1828 trial of James Abbott, who had cut his wife’s hands and throat with a knife, the newspapers of the day “teemed” with “horrible acts” of marital violence (Times, 3 October 1828, 3f). The change prompted by the 1828 act was that, with magistrates able to handle such cases, lesser assaults came to trial more often. The key difference was thus the level of violence in question. In the 1830s, I argue, common assault and battery in a familial context assumed unprecedented visibility in the public press. This decade, then, marks the cultural moment when—to use Kaye’s words—working-class wife assault became an “every-day story” (OW, 234).

It was not until the 1857 Divorce Act took effect that middle-class assaults received the same level of publicity. When the divorce court opened in January 1858 and divorce reporting became a regular feature of the daily press, a similar revolution in print culture occurred. The dates of 1828 and 1858 thus mark crucial turning points in the public visibility of spousal assault—1828 for working-class violence, 1858 for middle-class violence, the thirty-year time lag underlining the resistance to investigating or exposing the middle-class home. Despite this distinction, the 1828 act did have a significant effect on middle-class readers. First, and most obviously, it was middle-class readers who consumed most of the newspapers that covered the trials of abusive husbands in magistrates’ courts. Narratives of working-class spousal violence thus became part of middle-class culture. One might suppose that this public disciplining of working-class assaults allowed the middle-class readers of newspapers and novels to feel safely distanced from such violence. Yet, as I will argue, middle-class models of marriage infused both the press reports and the fictions of the period, even while their ostensible topic was working-class violence. This is especially relevant in light of D. A. Miller’s suggestion that the nineteenth-century novel played an important disciplinary role for the liberal subject. In The Novel and the Police, Miller suggests that the novel takes social discipline “out of the streets and into the closet”—that is, “into the private and domestic sphere on which the very identity of the liberal subject depends” (Miller, ix). Victorian novels, as I will show, take as a central theme the disciplining of spousal violence, both contemplating the public, legal means and creating one of the primary private means by which this was to occur.

This book, then, considers the following questions: In an era when print journalism accorded new visibility to wife assault, how did the middle-class domestic novel treat the phenomenon of “private” family violence? How did Victorian novelists participate in and respond to the urgent debates surrounding wife assault in the Victorian public press? My analysis will proceed chronologically from the early 1830s, through the intense debates on wife assault in the late 1840s and early 1850s, to the 1850s divorce debates and the opening of the new divorce court (when, once again, marital cruelty entered the public eye in unprecedented ways), and culminate in the fin de siècle, when late-Victorian feminism and the great marriage debate in the Daily Telegraph brought male sexual violence and the viability of marriage itself under scrutiny. Victorian novelists, I will suggest, were not separate from this scrutiny of marital conduct, but actively participated in it. Moreover, I will argue that their representations of domestic violence were charged with their relationship to a continuing debate, the urgency of which is still with us, but the terms of which at specific nineteenth-century moments we have now largely forgotten.

Notably, the wife-assault debates were linked to other, related Victorian debates about violence. Tropes of animal cruelty run through the novels in this study (battered women are repeatedly paralleled with beaten dogs or horses) and suggest the relationship between the wife-assault debates and the rise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) and the antivivisection campaigns for the more humane treatment of working, laboratory, and domestic animals. Moreover, Victorians linked wife and child abuse as two related forms of violence. The 1853 Act for the Better Prevention and Punishment of Aggravated Assaults upon Women and Children raised penalties for both these crimes, seen jointly as a violation of protective manliness and “a blot” on the “national character” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1414). This book focuses specifically on marital violence—that is, assault, cruelty, and rape—but at times will examine as well how Victorian texts linked violence toward animals or children with violence against married women.

In considering the relationship between legal cases and the novel, I will suggest that the newspaper played a central role in mediating between these two apparently very separate discourses. Court reporting in newspapers, as Shani D’Cruze and Barbara Leckie have shown, provided an important arena in which issues of gender, class, and “private” domestic conduct were publicly negotiated.7 The nineteenth-century domestic novel—with its scrutiny of intimate behavior and spaces—also functioned as a locus in which such negotiations occurred. Like Leckie, I perceive an intense relationship between the Victorian newspaper and the novel in their public scrutiny of “private” conduct, a relationship that was especially close in serial fiction, since this type of fiction, like newspaper reporting of legal trials, took place over time. Moreover, I will argue that the novel increasingly takes the public scrutiny of private conduct as a theme in itself, actively contemplating the construction of the private through and by the public eye of the newspaper.

When I started research on this topic, there was a dearth of literary scholarship on marital violence in Victorian literature. While literary critics had largely neglected the topic of spousal assault, I found that legal and social historians had amassed a rich and growing body of research on marital breakdown, marital cruelty, and marital violence in Victorian England, research that proved invaluable to my own. In the area of legal history, John M. Biggs provides a cogent history of the concept of matrimonial cruelty, while Maeve E. Doggett traces legal developments in the areas of marriage and wife beating in Victorian England, focusing especially on the husband’s right to beat and/or confine his wife. In particular, her book provides detailed analyses of the Cochrane decision of 1840 and the Jackson decision of 1891. Margaret May provides a useful introduction to changing patterns of and views on family violence in the nineteenth century, as well as an analysis of the major changes in marriage law between 1853 and 1914. Fruitfully combining feminist and legal history, Anna Clark’s 1992 article examines wife beating and the law in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while Mary Lyndon Shanley examines campaigns for marriage law reform between 1850 and 1895, focusing on changes to coverture, divorce, child custody, and married women’s property law. Shanley’s excellent chapter on wife abuse, conjugal rights, and marital rape is of particular relevance to anyone interested in nineteenth-century marital violence. Finally, A. James Hammerton melds social and legal history in his article “Victorian Marriage and the Law of Matrimonial Cruelty,” arguing that marital cruelty cases provide important evidence of shifting views on marriage, both in the judges’ domestic ideals and in the expectations and grievances of the applicants.8

On the subject of divorce and marriage breakdown, Allen Horstman’s seminal 1985 study traces the history of Victorian divorce before and after the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, providing insight into the development and use of cruelty as grounds for divorce. Hammerton’s invaluable book Cruelty and Companionship examines the experience of Victorian marital conflict in the working and upper classes, men and women. Thoroughly interdisciplinary, his book draws on newspapers, advice manuals, novels, working-class balladry, and novels, as well as legal cases, in tracing the dynamic and shifting views on marriage in this period. There is also excellent research on the social history of nineteenth-century working-class violence: Nancy Tomes documents the erosion of the working-class women’s “right to fight” in the mid-Victorian period; Ellen Ross provides a vivid picture of the causes and forms of working-class conflict from 1870 to 1914; and Clark’s article discusses the relationships among working-class culture, law, and politics as regards wife beating in the nineteenth century. Finally, D’Cruze looks at how physical and sexual violence impinged on Victorian working women. My research is deeply indebted to this rich collection of historical work, and I hope to bring it to bear on the large body of Victorian fictional material representing wife battery.9

Although there were no full-length studies of domestic assault in Victorian literature when I began my research, two books appeared as this manuscript neared completion: Marlene Tromp’s The Private Rod: Marital Violence, Sensation, and the Law in Victorian Britain (2000), and Kate Lawson and Lynn Shakinovsky’s The Marked Body: Domestic Violence in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Literature (2002). Lawson and Shakinovsky’s psychoanalytic study examines the violated bodies of middle-class women in mid-nineteenth-century fiction and poetry. They argue that “the representation of bourgeois women fades into blankness … as the safety of their domestic sphere is threatened” (Lawson and Shakinovsky, 2) and explore the repressions and evasions underlying these “haunting absence[s]” (Lawson and Shakinovsky, 17) in Victorian texts. Although I differ from Lawson and Shakinovsky in that I see marital violence as being urgently and centrally explored in nineteenth-century texts, whereas they argue that it is “evaded or set aside” (Lawson and Shakinovsky, 1), their study gives much-needed attention to the ways in which Victorian texts represent such violence and to the considerable tensions surrounding its representation. Their detailed readings of texts have both enriched and challenged my own. Because of its interdisciplinary interests in feminism, literature, and law, Marlene Tromp’s study is closest to my own. We both see a close relationship between fiction and the law relating to spousal assaults; however, while Tromp argues that sensation fiction anticipated legal developments later in the century, I see a more reciprocal and interlocutory relationship between the law and the novel on this issue. I also perceive a greater role being played by realist fiction and the newspaper in bringing marital violence into the public eye. While I sometimes differ from Tromp, I am always indebted to her insightful and detailed study.

This book, then, traces Victorian novelists’ intense engagement with the issue of marital violence from 1828 to 1904. Chapter 1 situates the early works of Charles Dickens against the fallout from the 1828 Offenses Against the Person Act, which brought accounts of working-class marital violence almost daily into the newspapers. Chapters 2 and 3 examine Dombey and Son and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall in the context of the intense debates on wife assault and manliness in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Chapter 4 reads “Janet’s Repentance” in light of the parliamentary debates on the 1857 Divorce Act. The opening of the divorce court in January 1858 made middle-class marital violence a regular item of interest in Victorian newspapers, and chapters 5 and 6 examine how divorce reporting informs The Woman in White and He Knew He Was Right (both of which derive their structures from marital cruelty trials). Locating the New Woman fiction of Mona Caird and the reassuring detective investigations of Sherlock Holmes in the context of late-Victorian feminism and the great marriage debate in the Daily Telegraph, the book’s two final chapters illustrate how fin-de-siècle fiction brought male sexual violence and the viability of marriage itself under public scrutiny.

The study as a whole, then, suggests that narratives of marital violence permeated Victorian middle-class culture, even as these very narratives threatened to undermine its central tenets of domesticity, marriage, and protective masculinity. I will argue that the newspaper played a key role in this probing of domestic life, as its pages were filled with revelations of marital violence in the working classes, after 1828, and the upper classes, after 1858. Nineteenth-century novelists, I will contend, reacted to this new probing of marital conduct, variously celebrating the loyalty of the passive woman who refuses such investigation, bringing middle-class violence into the public eye, building plots to reflect the structures of newspaper reports, and thematizing the role of the newspaper in modern life. As I will show, the novels of the period actively engage with the wife-assault debates of the nineteenth century; thus while Nancy Armstrong argues that domestic fiction “actively sought to disentangle the language of sexual relations from the language of politics,” I suggest that insofar as such fiction portrayed marital assault it was always more or less overtly political. If we have failed to see its politics it is because we—not its original readers—are separate from the parliamentary and media debates that created its contemporary relevance.10

Whereas Tromp sees the sensation fiction of the 1860s as having revealed middle-class violence in an unprecedented way, I feel that this shift was inaugurated earlier in the century, with the revelation of working-class violence after 1828, and then of middle- and upper-class violence after 1858. Moreover, I contend that realist fiction played a greater role in this revelation than Tromp recognizes, and sensation a lesser one. Marital cruelty was a late addition to Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s sensational Aurora Floyd (1863), for example, whereas it was always central to The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Dombey and Son.11 How, then, does this affect our view of realism, traditionally seen as upholding middle-class ideology and social structures? As I will show, such texts may depict marital violence as means of reasserting marriage as an ideal to be refined or corrected; they need not conclude that marriage is rotten because they depict rotten marriages. On the contrary, a number of texts in this study uphold marriage, domesticity, and the protective male as ideals even as they show women battered by brutal husbands. Indeed, the texts that openly question marriage—such as The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, “Janet’s Repentance,” and The Wing of Azrael—are the exception, not the rule. However, any representation of wife assault in nineteenth-century fiction implicitly opens fissures in middle-class ideology by pointing to gaps or flaws in the ideology of marriage, that cornerstone of Victorian gender relations. Such fictions highlight moments when the marital ideal is challenged, probed, or even destroyed, moments when writers and readers were forced to restore or repair this ideal or even to imagine its dissolution.