Читать книгу Bleak Houses - Lisa Surridge - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление|2|

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND MIDDLE-CLASS MANLINESS

Dombey and Son

In his sketch “Meditations in Monmouth Street” (Morning Chronicle, 11 October 1836), Charles Dickens turns his attention to the connection between manliness and domestic assault. Gazing at an array of secondhand men’s clothing in a shop—a boy’s suit, some corduroys and a round jacket stained with ink, a threadbare suit, a vulgar suit, a green coat with metal buttons, and a coarse common frock—he imagines the clothes as the possessions of one individual, the detritus of a life: “There was the man’s whole life written as legibly on those clothes, as if we had his autobiography engrossed on parchment before us” (SB, 78). From the schoolboy in the inky suit to the ruffian in the coarse frock, he reads the man’s moral deterioration in the clothing. Crucially, the man’s imagined moral descent is signaled by acts of domestic assault: Dickens pictures him hitting his mother with a “drunken blow” and striking his wife as she holds a “sickly infant, clamouring for bread” (SB, 79, 80). Finally, Dickens imagines the mother dying in poverty and the family destitute, while the man (now a criminal) is transported and dies a lingering death. “Meditations in Monmouth Street,” then, depicts manly virtue eroding into laziness, drunkenness, domestic violence, and crime. The sketch thus deploys family violence as a key sign of lost manliness. As a Times editorial stated on 12 March 1853, “a man [shows] that he has no claim to consideration as a man by acts of brutal violence against a woman or a child” (6d).

While the sketch “Meditations in Monmouth Street” focuses on violence against women as a sign of lost manliness, Dickens’s other early writings reveal a nascent interest in the conscience of the male abuser. In Jack’s sobbing in “The Hospital Patient,” and Sikes’s haunting by Nancy in Oliver Twist, Dickens probes the possibility of the abuser’s redemption even as he celebrates female passivity. In Dickens’s early work these are still gestures; the central point of narrative interest remains the abused woman. In 1846–48, however, Dickens published Dombey and Son, his full anatomy of failed manliness. Here, as in the Monmouth Street sketch, domestic assault marks the nadir of masculine failure, in this case in Mr. Dombey’s descent from Victorian businessman and paterfamilias to lonely bankrupt. When Dombey’s wife leaves him (as he thinks) for his business manager, Mr. Carker, he fantasizes about “beating all trace of beauty out of [his wife’s] triumphant face with his bare hand” (DS, 636). Instead, in his impotent rage, he strikes his daughter Florence in the central hall of their home, conflating the women in a symbolic assault on both of them. When he commits this assault on wife and child, his business, his home, and his very identity collapse. Through his inability to understand his obligations within the domestic sphere—in particular his duty to protect wife and child—the successful middle-class businessman falls into the role of the abuser, widely perceived by Victorians as that of the unmanly and unclassed. Paradoxically, then, even as Dombey and Son draws public attention to middle-class family violence, the text’s symbolic language—of slums, tenements, and class descent—still points to the identification of such violence with the working class.

“Much More a Man’s Question”

That Dickens should turn his attention in Dombey and Son to the connections between manliness and family violence points to a growing trend in the 1840s and 1850s for Victorians to see domestic assault as a man’s issue. Lewis Dillwyn, MP for Swansea, exemplified this trend when in 1856 he introduced to the House of Commons a bill proposing flogging as punishment for wife abusers. He described wife assault as “not altogether a woman’s question, but … much more a man’s question.” As he urged the all-male House of Commons, “It concerned the character of our own sex that we should repress these unmanly assaults” (142 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 169; my emphasis). In Dickens’s interest in masculinity and domestic assault—evident in his early sketches and fiction and central to Dombey and Son—he joined in a growing tendency to scrutinize men’s marital behavior and to connect manhood with the cherished Victorian ideal of domesticity.

The Victorians’ regulation of domestic violence partook of their “progressive construction of men’s conjugal behaviour … as a problem to be regulated” (Hammerton, Cruelty, 6–7) and in turn signals the period’s shifting definitions of masculinity. As Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall document in Family Fortunes, the early nineteenth century witnessed the construction of a new subject position—that of the bourgeois man for whom manliness was inextricably linked to domesticity: “[M]iddle-class men who sought to be ‘someone,’ to count as individuals because of their wealth, their power to command or their capacity to influence people, were, in fact, embedded in networks of familial and female support which underpinned their rise to public prominence” (Davidoff and Hall, 13). For the Victorian middle-class male, Davidoff and Hall argue, domestic harmony thus represented the “crown of the enterprise as well as the basis of public virtue” (Davidoff and Hall, 18). This bourgeois script equated British manliness with self-control over both sexual and violent urges.1 Violence in the home thus destroyed the two central facets of Victorian manliness: it shattered the connection between manliness and domesticity and it showed a man unable to exercise self-control. Hence Dillwyn could characterize wife assault as “much more a man’s question” than a woman’s (142 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 169).

As I will show, Dombey and Son forms part of this discourse that constructed family violence as a threat to masculinity. It represents Dombey’s injury to his daughter as a symbolic assault—a blow, a murder—on his own manliness. And, paradoxically, the text closes with Dombey’s manhood restored by means of, rather then despite, his daughter’s injury. As I will argue, this renders the novel closed to the implications of its own central narrative event. As Anna Clark observes, marital violence threatened Victorian patriarchy because it disrupted the idea that men protected women in the home (A. Clark, “Humanity,” 187). Domestic violence was thus a kind of oxymoron, explosive in its implications for Victorian middle-class values. This threat to the patriarchal home underlies the central section of Dombey and Son, when Edith and Florence, Dombey’s wife and child, leave the Dombey home, and the house itself becomes a symbolic ruin, permeable to the gaze of all onlookers. Yet finally the text allays rather than confronts this threat. By restoring Mr. Dombey to domestic harmony at its conclusion, the text focuses on recreating protective manliness rather than critiquing the unequal gender relations underlying spousal assault. This closure, however, is unstable: in order to reconstitute the home, the text excludes and vilifies Edith, its most powerful female figure, just as The Old Curiosity Shop dismisses the combative Mrs. Jiniwin. Hence both Dombey and Son and The Old Curiosity Shop reveal an uneasiness about female independence and protest, specters fast becoming reality when Dombey and Son was serialized between 1846 and 1848.

Constructing Manliness: The “Good Wives’ Rod” and the Cochrane Decision

Before analyzing Dombey and Son, I want to look at the parliamentary debates on the 1853 Bill for the Better Prevention and Punishment of Aggravated Assaults upon Women and Children to illustrate that members of Parliament described family violence as an assault on manliness. On 10 March 1853, Mr. Fitzroy, Undersecretary of the Home Department, rose in the House of Commons to propose a bill to “enlarge magistrates’ powers to inflict summary penalties for brutal assaults on women and children” (Doggett, 106). This bill, dubbed the “Good Wives’ Rod,” became the first piece of legislation to perceive assaults on women and children as a distinct category (May 1978, 144, 136); it thus formally inaugurated the very category of “family violence” as opposed to assault in general. It increased the maximum penalties under the 1828 Offenses Against the Person Act to £20 or six months in prison (with or without hard labor) and made it possible for a third party witnessing an assault to bring a complaint to a magistrate (Doggett, 106–7). As he introduced his bill, Fitzroy argued that assaults on women and children constituted “a blot” on the “national character” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1414). Addressing the all-male House of Commons, Fitzroy constructed a manly middle-class Englishman revolted by press accounts of wife assault: “No one could read the public journals without being constantly struck with horror and amazement at the numerous reports of cases of cruel and brutal assaults perpetrated upon the weaker sex by men who one blushed to think were Englishmen, and yet were capable of such atrocious acts. One’s mind actually recoiled when he thought of the dastardly and cowardly assaults which were being constantly perpetrated upon defenceless women by brutes who called themselves men” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1414). Fitzroy repeatedly emphasized the inadequacy of the justice system as he read out cases from 1852 and 1853. (Interestingly, although the proposed bill was to cover women and children, it was the wife beater, that “brute in the form of a man” [124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1414] who drew Fitzroy’s attention, as not one of these cases involved abused children.) His speech contrasted manliness, courage, and humanity with the brutal, cowardly, and inhuman qualities of the wife beater. Moreover, the speech used horror at marital violence as a marker of true Englishness, and crimes against women as a betrayal of nationhood. Fitzroy’s point was that a true Englishman could neither beat his wife, nor bear to read in the newspapers about others doing so. Genuine British manliness, he suggested, was incompatible with committing or countenancing marital violence.

In the late 1840s and early 1850s, a period of growing journalistic and political activity on the subject of domestic assault, Victorians who sought to solve the problem of wife assault approached the issue from two distinct ideological positions. The first, exemplified by Fitzroy, represented men as women’s natural protectors. Advocates of this position embraced a manly ideal combining authority with self-control, and sought greater punishments for men who violated standards of masculinity by using violence against the “weaker sex” (124 Parl. Deb 3s., col. 1414). One can distinguish from this the emergent feminist position that held that wife beating was a symptom of women’s legal nonexistence. This view was put forward by John Stuart Mill, Helen Taylor, and Barbara Leigh Smith, all of whom tried to change laws governing marital coverture and married women’s property. But these positions were by no means mutually exclusive. Mill, for example, one of the most passionate advocates for corporal punishment, at times characterized women as weak and in need of protection. In “Protection of Women” (Sunday Times, 24 August 1851), he described assault victims as “helpless, virtuous, unoffending creatures,” and their assailants as “bipedal monsters” and “brute beasts” (PW, 2b). It is characteristic of the complexity of gender relations and feminism in the 1850s that Caroline Norton (one of the most forceful advocates for feminist legal reform) both deplored the legal nonexistence of married women and asserted her inferiority to men: “The natural position of woman is inferiority to man,” she wrote. “Amen! .… I am Mr Norton’s inferior; I am the clouded moon of that sun.… Put me under some law of protection” (LQ, 98–99). In this moment of ideological contest, debate on the 1853 “Good Wives’ Rod” very largely represented the former position: most MPs perceived wife and child assault as a symptom of men’s failure to act as guardians or protectors of the weak. MPs thus defended male superiority while seeking to ensure the correct use of male power. Parliament, then, became one of many forums in which the ideal of manly self-control was defined and enforced.

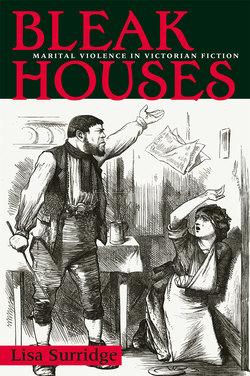

The 1853 bill was relatively uncontentious, indicating the widespread perception that something needed to be done about wife assault, a problem that feminists and nonfeminists alike perceived as being on the increase (Doggett, 115).2 The Times supported the measure (12 March 1853, 6d), and Punch wrote, “Mr. Fitzroy deserves eternal honour for having taken up the cause of the ill-used Women” (19 March 1853, 119). The only substantial issues of debate were whether flogging should be added as a punishment for assaults against women and children, and whether a magistrate should have the summary power to inflict as substantial a penalty as a £20 fine or a six-month prison sentence. The flogging amendment was proposed by Mr. Phinn, who argued that corporal punishment was appropriate “where men were already reduced below the level of the brute” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1419). It was supported by the Times (12 March 1853), which argued that “there can be no question of ‘degrading’ a man who inflicts a course of violent and continued brutality upon a woman or a child. The truth is, the brute is so degraded already that, short of miracles, his fears constitute the only channel by which his actions can be touched” (6d). Punch also supported flogging “in a clear case of brutality towards a woman”—the article does not mention children—arguing that “nothing can be too degrading for one who degrades himself in the manner alluded to” (19 March 1853, 119). Finally, Mill threw his weight behind the measure, arguing in an anonymous and privately printed pamphlet on Fitzroy’s bill, “Overwhelming as are the objections to corporal punishment except in cases of personal outrage, it is peculiarly fitted for such cases” (CW, 21:105). (Unlike Punch, Mill mentions assaults on both women and children; notably, he also was able to imagine assaults on children by women, a possibility that others seem to have overlooked.) Ultimately, however, the amendment failed by a two-to-one margin, as most MPs agreed with Fitzroy that flogging was “inconsistent with the feeling of the age” (125 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 677).3 What public and parliamentary discussion there was on Fitzroy’s bill, however, provides important evidence that domestic assault was widely perceived as a violation of manliness, an act of men “reduced below the level of the brute” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1419), and a betrayal of British values, as Punch communicated with its Orientalized image of a “Tyrant” man wielding force over his wife (16 April 1853, 158; fig. 2.1). Implicit too, was the assumption that family violence characterized lower-class men who could not control their passions as middle-class mores increasingly demanded. Hammerton observes, “Middle-class manliness, denoting protectiveness and benevolence to women, as well as undisputed power, was … compromised by the unruly men of the lower classes” (Hammerton, Cruelty, 61). Describing abusive men as brutes, sympathetic MPs represented beaten wives as “defenceless,” “soft,” and “kindly” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1414, 1417), loyal to their abusers and unwilling to testify against them. Earl Granville, speaking in the House of Lords, deplored the “cases of great cruelty, wholly wanton and unprovoked, committed by brutal husbands upon their defenceless wives and children” (127 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 551). Implicit in the descriptions of brutal men and defenseless wives and children was the middle-class expectation that the husband should protect—not abuse—his family. This argument applied with particular force to women, assumed to deserve protection from all men. As Viscount Palmerston argued in the House of Commons, “He did not at all admit that a man was more entitled to commit these injuries upon his own wife, than upon another man’s wife. On the contrary, he thought that it was a greater offence. His own wife was more entitled to expect protection, and another man’s wife had her own husband to guard her from injury” (125 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 680). Debates on the 1853 bill thus illustrate how legislative attempts to control family violence were fueled by middle-class ideals of masculine behavior. Focusing on the right role of men much more than on the rights of women, MPs sought to correct male behavior while preserving middle-class gender roles. Important as the 1853 act was to women suffering assault, it was based on an idea of wife battery as a violation of cherished gender norms, an offence of the brutal against the weak. The act was premised on the physical and moral supremacy of men in marriage. It sought not to limit that power but to correct its application.

Figure 2.1. Illustration for “Panel for the Protection of Ladies,” Punch 24 (1853): 158.

The Closed Home

While MPs in 1853 harnessed shifting ideals of manliness to counter the problem of marital violence, they worked within the doctrine of coverture, which authorized very extensive powers to the husband. At midcentury, the doctrine of coverture had been reinforced by the 1840 Cochrane decision, which enforced the “general right of the husband to the control and custody of his wife” (Times, 12 June 1840, 7e).4 The facts of the Cochrane case were as follows: Cecelia Maria and Alexander Cochrane married in 1833. In 1836, Cecelia Cochrane left her husband, taking their young son, and went to live with her mother in Ireland and France. Alexander Cochrane successfully applied for a writ for restitution of conjugal rights. The writ was not effective while Cecelia was in Ireland, but in May 1840 she was “induced by a strategem” (Times, 12 June 1840, 7d) to come to England and to go to her husband’s lodgings. Alexander “immediately placed her in custody” and kept her in his rooms, despite her declaration that “whenever she has it in her power she will again run away” (Times, 12 June 1840, 7d). Part of Alexander Cochrane’s concern, he told the judge, was that while in Paris, Cecelia had attended “masked balls and other places of that description, in the company of persons unknown to [him]” (Re Cochrane [1840] 8 Dowling 631). Cecelia Cochrane herself applied for a writ of habeus corpus, and the court had to decide whether her husband had the “right to restrain her of her liberty until she [was] willing to return to a performance of her conjugal duties” (Re Cochrane [1840] 8 Dowling 630).

The Cochrane case points to a number of unspoken anxieties underlying early Victorian male authority. As Anna Clark notes, in the ideal of the Victorian middle-class home the wife was “sheltered, safe and submissive” (A. Clark, “Humanity,” 192). In theory, no interference should have been required if the wife observed the marriage contract. But what if, like Cecelia Cochrane, a wife refused to acknowledge the husband’s authority? What powers did husbands such as Alexander Cochrane have to enforce their “natural” authority? How far should the state intervene in the domestic sphere?

The Cochrane decision reveals that for Victorian wives, there was force behind the idea that the husband ruled the household. In this precedentsetting case, the judge supported Alexander Cochrane’s rights to confine his wife and hold her to the provisions of the marriage contract. The judge gave Cecelia Maria two options: to stay in the marriage willingly, or by constraint: “[I]f there be any thing painful to Mrs. Cochrane in the present state of things, she cannot properly complain of it; for it arises from her own breach of duty, and she may end it when she pleases by cheerfully and frankly performing the contract into which she has entered. The moment that she makes restraint of her person to be unnecessary for keeping in the path of duty, the restraint will become illegal” (Times, 12 June 1840, 7e). The Cochrane decision clearly articulates the assumptions about male authority in marriage that underlay the more idealizing rhetoric of the 1853 debates in the British Parliament. It shows the extent to which the state delegated its authority to the husband, recognizing him as the center of authority in the home and supporting his powers there. (Feminist Caroline Frances Cornwallis summarized the implications of the Cochrane case for women in the pages of the radical Westminster Review: “[T]he common law views the relation of husband and wife as that of master and bondswoman. A hired servant could not be so treated” [PMW, 187n].) The decision also reveals how deeply reluctant the courts were to intervene in the domestic sphere. The issue of wife assault, then, pitted the new scrutiny of male marital conduct against the state’s reluctance to interfere in the middle-class private realm.

Dombey and Son: The Failure of Middle-Class Manliness

Charles Dickens’s novels focus repeatedly on cruelty to women and children. In particular, Bleak House, serialized from March 1852 to September 1853, coincided with and reflected the concerns of the parliamentary debates on the 1853 act. Dickens’s intensely sympathetic portrayal of Allan Woodcourt aiding Jenny, the abused brick maker’s wife (chapter 46, part 14), was published in April 1853, the month after Fitzroy proposed his act in the House of Commons. Moreover, Bleak House was perceived as an intervention in the wife-assault debates of the early 1850s, as is evident from J. M. Kaye’s 1856 article “Outrages on Women,” which references the brick makers’ episode (OW, 251–53). However, Bleak House, like Oliver Twist and Sketches by Boz, located violence in the lower-or lower-middle-class home and family, as did the 1853 parliamentary debates. For this reason, this chapter focuses on Dombey and Son, which takes the far less conventional step of portraying violence in the middle-class home. Unlike Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist, or even the aspiring office boy of “Meditations in Monmouth Street,” Dombey belongs to the middle class, the class to which Dickens’s readers largely belonged. There is a crucial distinction between Dickens’s portrayal of Sikes and Nancy’s violent relationship and his portrayal of violence in the Dombey home. As Tromp notes, Oliver Twist insulates the middle class from violence (Tromp, 24). Dombey and Son refuses the reader any such distance. Dickens’s portrayal of violence in the Dombey home is highly significant. While lacking the gruesome physicality of Nancy’s murder, Dombey’s assault on his daughter and wife constitutes an assault on contemporary ideals of middle-class manliness, an assault that hit very close to home for many readers of the novel. Far from buttressing middle-class status by portraying the lower classes or the gentry as violent, Dombey and Son worked to expose domestic violence in the middle-class home. Dickens’s text, however, simultaneously reveals a deep ambivalence concerning state intervention there. Even as it portrays the Dombey home as subject to the same male violence found in the police courts and the newspapers, and even as it invites the reader to participate in the public scrutiny of the middle-class home, the text recoils from prying eyes and attempts to reconstitute the middle-class home as a private space. Endorsing the Cochrane decision’s construction of the middle-class home as a space in which interference should be minimized, the novel thus attempts to resolve the issue of domestic assault within the home itself.

In Dombey and Son, the narrator pleads for “a good spirit who would take the house-tops off, with a more potent and benignant hand than the lame demon [Asmodeus] in the tale” (DS, 620).5 To a large extent, the novel realizes this Asmodean ambition. Serialized between 1846 and 1848, roughly six years after the Cochrane decision and five years before the 1853 act, the novel showed middle-class readers a home of their own social stratum torn by family violence. And such violence is not merely incidental to the text. The novel’s structural fulcrum is chapter 47 (“The Thunderbolt”), in which Dombey strikes his daughter, Florence. More complex still, the narrative establishes through setting, symbol, and parallelism that Dombey’s assault on Florence substitutes for his desire to beat his wife Edith, whom he suspects of adultery. Thematically and structurally, this assault lies at the center of the text.

The anatomy of Mr. Dombey’s failed manliness begins in the novel’s first chapters. These depict the relationships between men, women, and two houses—the commercial House of Dombey and Son and the domestic house of the Dombey family. These early chapters invoke the key Victorian assumption (elucidated by Davidoff and Hall in Family Fortunes) that the House of Dombey and the house of the Dombeys are inseparable enterprises, and will succeed or fail together. As Gail Turley Houston argues, Dombey and Son thus “foregrounds the way the Victorian economic system was founded on family relations, more particularly, those between men and their mothers, wives, daughters, and sisters.”6 The text strongly suggests that feminine nature—which the narrator describes as “a nature that is ever, in the mass, better, truer, higher, nobler, quicker to feel, and much more constant to retain, all tenderness and pity, self-denial and devotion, than the nature of men” (DS, 29)—has the potential to redeem “the rapacious nature of capitalist England” (Houston, 91). Mary Poovey notes that in the nineteenth century, femininity was thus seen as capable of “mitigat[ing] the effects of the alienation of market relations”; by representing female work as selfless—and thereby distinguishing it from paid labor—Victorians were able to construct the home as a space of “(apparent) non-alienation.”7 Dombey, however, fails to mitigate his capitalist alienation through associating himself with redemptive femininity in the domestic sphere. He neglects his first wife as well as his daughter in favor of his capitalist enterprise (ironically named the “House of Dombey”). In his second marriage, Dombey misconstrues the relations between the private and public spheres when he chooses his bride, Edith Granger—“very handsome, very haughty, very wilful”(DS, 280)—based on her ability to represent his commercial persona in public. Finally, Dombey confuses the private and the public when he delegates his business manager, Carker, to exercise his authority over his wife. These errors, according to the text’s logic, constitute a failure of manhood, a failure that is conveyed symbolically through a number of discreet allusions to impotence.8 The House of Dombey will fail because Dombey, the “Head of the Home Department,” is neither the father nor the man that contemporary bourgeois expectations demand.

While the novel’s opening thus foretells Dombey’s failure to understand women’s ability, under the Victorian gender system of separate spheres, to redeem the competitive and aggressive lives of men, the text represents this failure in a key central trope—that of domestic assault. The specter of marital violence appears early in the text, immediately after Mrs. Dombey’s funeral. In an act whose symbolism eludes him, Mr. Dombey orders the furniture swathed in newspapers and holland:

When the funeral was over, Mr. Dombey ordered the furniture to be covered up.… Accordingly, mysterious shapes were made of tables and chairs, heaped together in the middle of rooms, and covered over with great winding-sheets. Bell-handles, window-blinds, and looking-glasses, being papered up in journals, daily and weekly, obtruded fragmentary accounts of deaths and dreadful murders. Every chandelier or lustre, muffled in holland, looked like a monstrous tear depending from the ceiling’s eye. Odours, as from vaults and damp places, came out of the chimneys. The dead and buried lady was awful in a picture frame of ghastly bandages. (DS, 24)

The muffling and bandaging are highly symbolic: the Dombey home, always neglected, now becomes a house of death. Muffled in holland, Mrs. Dombey’s portrait seems swathed in “ghastly bandages” (DS, 24). As the metaphor of bandaging powerfully suggests, there lurks in this house the threat of violence, injury, and wounding—specifically, injury to women. What form that injury might take is ominously suggested by the pages of “journals, daily and weekly” that wrap the furniture, bellpulls, and looking glasses. From these newsprint sheets, the narrator tells us, “obtrud[e] fragmentary accounts of deaths and dreadful murders.” The real fear that haunts the House of Dombey is that the dreadful crimes of the daily and weekly newspapers will, through Dombey’s failure to understand the value of women’s ideological work in the Victorian gender system, come to rest in the middle-class home.

Part 1 of the serial version of Dombey and Son (which contains the description of “accounts of death and dreadful murders” obtruding from the newspapers muffling the furniture and portrait) was published in October 1846. A perusal of the Times for September and October 1846 reveals the crimes that haunted the Victorian cultural imagination at this time: marital assault and wife murder. As a Times editorial noted, “instances of brutality on the part of a husband towards a wife” had “of late been very numerous” (Times, 24 August 1846, 4d). The police reports of the Times from the autumn of 1846 contain a litany of violent crimes against women:

WORSHIP-STREET.—An elderly man, named Richard Tweedy, described as a foreman in the London Docks … was placed at the bar, yesterday, before Mr. BROUGHTON, charged with cutting and wounding his wife, Catherine Tweedy, with intent to murder her. (Times, 1 September 1846, 6d)

WORSHIP-STREET.—A few days ago a young married woman named Anne Guest, whose face was shockingly cut and contused, and one of her eyes closed up, applied to Mr. BROUGHTON for an assault warrant against James Guest, her husband, a journeyman dyer, living in White-cross place, Finsbury. (Times, 17 September 1846, 7d)

WORSHIP-STREET.—Yesterday Edward Spiller, a middle-aged man of respectable appearance, described as lately a publican, was brought up on a warrant before Mr. BROUGHTON, charged with violently assaulting his wife, Caroline Spiller, and also conspiring with another man, now in custody, named Thomas Byrne, to effect a capital offence upon her person. (Times, 24 September 1846, 7b)

MANSLAUGHTER IN LIVERPOOL.—An inquest was held before Mr. P.F. Curry, borough coroner, on Wednesday, upon view of the body of Catherine Tully, of Thomas-street, in this town, who met her death by kicks in the abdomen, received from her husband. (Times, 25 September 1846, 5e)

MARLBOROUGH-STREET.—Robert Long Andrews, a young man, was summoned by Fanny Andrews his wife, for ill-treatment. (Times, 2 October 1846, 6e)

WORSHIP-STREET.—Yesterday a young man named Alfred Wilton, described as a boot and shoemaker, was placed at the bar before Mr. BROUGHTON, charged with causing the death of his wife, Sarah Wilton, a young woman aged 19, by drowning in the Regent’s Canal. (Times, 20 October 1846, 6f)

WORSHIP-STREET.—Yesterday a middle-aged man, named John Lacy, was placed at the bar before Mr. BROUGHTON, charged with brutally assaulting his wife, Ann Lacy. (Times, 22 October 1846, 8d)

As I argue in chapter 1, newspaper accounts of wife-beating trials in magistrates’ courts had been a new phenomenon in the 1830s after the 1828 act came into effect. By the time Dickens was writing Dombey and Son in 1846–48, these stories were all too common. Yet they still held power to shock. This power is revealed in Fitzroy’s speech when he introduced his “Good Wives’ Rod” to the House of Commons in 1853: his most powerful rhetorical argument in favor of the bill was reading wife-assault cases verbatim from the newspapers. In Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, a full column and a half is filled with these paragraph-long synopses of predominantly lower-class spousal assaults, each of which, Fitzroy argued, should strike the imagination with “horror and amazement” (124 Parl. Deb. 3s., col. 1414). Fitzroy’s speech is fascinating because he foregrounds the shocking moment at which these (apparently alien) lower-class crimes entered the consciousness of the middle-class newspaper reader. (This contrasts with Punch, which in 1849 depicted a lower-class man reading accounts of domestic murder in the newspaper, and with his home papered with illustrations of gibbets and of criminals such as James Greenacre [fig. 2.2].) Like Fitzroy’s speech, the depiction of the Dombey house points to the moment when middle-class domesticity is shattered by the kind of violence associated with the magistrates’ courts and the newspaper. The fear of this tainting suggestively links the “ghastly bandages” on the portrait of the first Mrs. Dombey with the “fragmentary accounts” obtruding from daily and weekly papers. The threat that hangs over the house of Dombey is that of wife assault.

Dombey and Son thus suggests that unmitigated male aggression in the marketplace—that is, capitalist aggression that is not balanced by selfless female labor in the home—will lead to uncontrolled acts of domestic assault more commonly associated with the Victorian working class.9 Dickens thus represents domestic violence in Dombey and Son as symptomatic not of a problem in the gender system but of Mr. Dombey’s failure to recognize the rightness of the current gender system and to benefit from its self-regulating properties. Like the 1853 act which followed its publication, Dombey and Son thus seeks not to change gender relations but to reassert and reinforce them.

The threat of domestic violence is realized in chapter 47, suggestively entitled “The Thunderbolt.” Domestic assault shatters the house of Dombey when Mr. Dombey discovers that his second wife, Edith, has left him for his business manager, Mr. Carker. The narrator states explicitly that Dombey’s first impulse is to assault his wife: “He read that she was gone. He read that he was dishonoured. He read that she had fled, upon her shameful wedding-day, with the man whom he had chosen for her humiliation; and he tore out of the room, and out of the house, with a frantic idea of finding her yet, at the place to which she had been taken, and beating all trace of beauty out of the triumphant face with his bare hand” (DS, 636). Edith has left, however, so Dombey strikes his daughter instead: “[I]n his frenzy, he lifted up his cruel arm and struck her, crosswise, with that heaviness, that she tottered on the marble floor; and as he dealt the blow, he told her what Edith was, and bade her follow her, since they had always been in league” (DS, 637). The text makes it clear that Dombey conflates his daughter with his supposedly adulterous wife—this is a combined act of wife and child assault. Such an assault signals his failure to control his wife and his failure to protect the weak. In contemporary terms, it means that self-regulating system of the middle-class home—whereby male market aggression was regulated by the female economy of selflessness—has failed, and that his home has been destroyed from within. Interestingly, however, at the level of representation, Dombey’s assault catapults him out of the middle class and into the realm of police reports and newspaper journalism. As Mr. Toots says with unwonted accuracy, Mr. Dombey has become “a Brute” (DS, 672).10

Figure 2.2. “Useful Sunday Literature for the Masses; or, Murder Made Familiar,” Punch 17 (1849): 117.