Читать книгу Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali - Литагент HarperCollins USD - Страница 7

ОглавлениеIntroduction to the New Edition by B. K. S. Iyengar

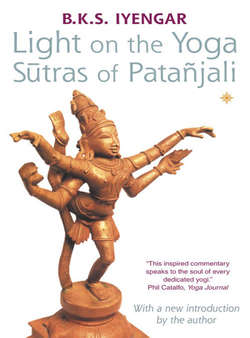

I express my sense of gratitude to Thorsons, who are bringing out my Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali in this new attractive design, as a feast not only for the physical eyes but also for the intellectual and spiritual eye.

As a mortal soul, it is a bit of an embarrassment for me with my limited intelligence to write on the immortal work of Patañjali on the subject of yoga.

If God is considered the seed of all knowledge (sarvajña bijan), Patañjali is all knower, all wise (sarvajñan), of all knowledge. The third part of his Yoga Sutras (the vibuti pada) makes it clear to us that we should respect him as a knower of all knowledge and a versatile personality.

It is impossible, even for sophisticated minds, to comprehend fully what knowledge he had. We find him speaking on an enormous range of subjects – art, dance, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, physics, chemistry, psychology, biology, neurology, telepathy, education, time and gravitational theory – with a divine spiritual knowledge.

He was a perfect master of cosmic energy; he knew the pranic energy centres in the body; his intelligence (buddhi) was as clean and clear as crystal and his words express him as a pure perfect being.

Patañjali’s sutras make use of his great versatility of language and mind. He clothes the righteous and virtuous aspects of religious matters with a secular fabric and in so doing is able to skilfully present the wisdom of both the material and the spiritual world, blending them as a universal culture.

Patañjali fills each sutra with his experiential intelligence, stretching it like a thread (sutra), and weaving it into a garland of pearls of wisdom to flavour and savour by those who love and live in yoga, as wise-men in their lives.

Each sutra conveys the practice as well as the philosophy behind the practice, as a practical philosophy for aspirants and seekers (sadhakas) to follow in life.

What is sadhana?

Sadhana is a methodical, sequential means to accomplish the sadhana’s aims in life. The sadhana’s aims are right duty (dharma), a rightful purpose and means (artha), right inclinations (kama) and ultimate release or emancipation (moksa).

If dharma is the atonement of duty (dharma sastra), artha is the means to purification of action (karma sastra). Our inclinations (kama) are made good through study of sacred texts and growth towards wisdom (svadhyaya and jñana sastra), and emancipation (moksa) is reached through devotion (bhakti sastra) and meditation (dhyana sastra).

It is dharma that uplifts man who has fallen physically, mentally, morally, intellectually and spiritually, or who is about to fall. Therefore, dharma is that which upholds, sustains and supports man.

These aims are all stages on the road to perfect knowledge (vedanta). The term vedanta comes from Veda, meaning knowledge, and anta meaning the end of knowledge. The true end of knowledge is emancipation and liberation from all imperfections. Hence the journey, or vedanta, is an act of pursuit of the vision of wisdom to transform one’s conduct and actions in order to experience the ultimate reality of life.

Due to lack of knowledge or misunderstanding, fear, love of the self, attachment and aversion with respect to the material world, one’s actions and conduct become disturbed. This disturbance shows as lust (kama), wrath (krodha), greed (lobha), infatuation (moha), intoxication (mada) and malice (matsarya). All of these emotional turbulences affect the psyche by veiling the intelligence.

The yoga sadhana of Patañjali comes to us as a penance in order to minimise or eradicate these disturbed and destructive emotive thoughts and the actions that accrue from them.

The yoga sadhana of Patañjali

The Sadhana is a rhythmic, three-tiered practice (sadhana-traya), covering the eight aspects or petals of yoga in a capsule as kriya yoga, the yoga of action, whereby all actions are surrendered to the Divinity (see Sutra II.1 in the sadhana pada). These three tiers (sadhana-traya) represent the body (kaya), the mind (manasa) and the speech (vak).

Hence:

At the level of the body, tapas, or the drive towards purity, develops the student through practice on the path of right action (karma marga).

At the level of the mind, through careful study of the self and the mind in it’s consciousness, the student develops self-knowledge, svadhyaya, leading to the path of wisdom (jñanamarga).

Later, profound meditation using the voice to pronounce the universal aum (see Sutras I.27 and 28) directs the self to abandon ego (ahamkara), and to feel virtuousness (silata), and so it becomes the path of devotion (bhakti marga).

Tapas is a burning desire for ascetic, devoted sadhana, through yama, niyama, Asana and pranayama. This cleanses the body and senses (karmendriya and jñanendriya), and frees one from afflictions (klesa nivrtti).

Svadhyaya means the study of the Vedas, spiritual scriptures that define the real and the unreal, or the study of one’s own self (from the body to the self). This study of spiritual science (atma sastra) ignites and inspires the student for self-progression. Thus svadhyaya is for restraining the fluctuations (mano vrtti nirodha) and in its wake comes tranquillity (samadhana citta) in the consciousness. Here the petals of yoga are pratyahara and dharana, besides the former aspects of tapas.

Isvara pranidhana is the surrender of oneself to God, and is the finest aspect of yoga sadhana. Patañjali explains God as a Supreme Soul, who is eternally free from afflictions, unaffected by actions and their reactions or by their residue. He advises one to think of God through repeating His name (japa), with profound thoughtfulness (arthabhavana), so that the seeker’s speech can become sanctified and thus the seed of imperfection (dosa bija) or defect be eradicated (dosa nivrtti) once and for all.

From here on, his sadhana continues uninterruptedly with devotion (anusthana). This practice, (sadhana-ana) will go on generating knowledge until he touches the towering wisdom (see Sutra II.28 in the sadhana pada).

Through the capsule of kriya yoga, Patañjali explains the cosmogony of nature and how to ultimately co-ordinate nature, in body, mind and speech. Through discipline tapas, study – svadhyaya, and devotion – Isvara pranidhana, the student can become free from nature’s erratic play, remaining in the abode of the Self.

In Sutra II.19 in the sadhana pada, Patañjali identifies the distinguishable, or physically manifest (visesa) marks and the non-distinguishable, or subtle, (avisesa) elements which comprise existence and which are transformed to take the individual to the noumenal (linga) state. Then through astanga yoga, coupled with sadhana-traya, all nature, or prakrti (alinga) becomes one, merged.

He defines the distinguishable marks of nature as the five elements: earth, water, fire, air and ether; (pañca-bhuta); the five organs of action (karmendriya); the five senses of perception (jñanendriya), and the mind (manas). The non-distinguishable marks are defined as the tanmatra (sound, touch, shape, taste and smell) and pride (ahamkara). These twenty-two principles have to merge in mahat (linga), and then dissolve in nature (prakrti). The first sixteen distinguishable marks are brought under control by tapas – practice and discipline, the six undistinguishable ones by svadhyaya – study and abhyasa – repetition. Nature, prakrti, and mahat,the Universal Consciousness, become one through and in Isvara pranidhana.

At this point all oscillations of the gunas that shape existence terminate and prakrtijaya, a mastery over nature, takes place. From this quiet silence of prakrti, Self (purusa) shines forth like the never fading sun.

In the Hathayoga Pradipika Svatmarama explains something very similar. He says that the body, being inert, tamasic, is uplifted to the level of the active, rajasic, mind through Asana and pranayama with yama and niyama. When the body is made as vibrant as the mind, through study, svadhyaya and through practice and repetitions, abhyasa, both mind and body are lifted towards the noumenal state of sattva guna. From sattva guna the sadhaka follows Isvara pranidhana to become a gunatitan (free from gunas).

Patañjali also addresses Svatmarama’s explanation of the different capabilities and therefore expectations for weak (mrdu), average (madhyama) and outstanding (adhimatra) students (see I.22). He guides the most basic beginner (the tamasic sadhaka) to follow yama, niyama, Asana, and pranayama as tapas, to become madhyadhikarins (vibrant and rajasic), and to intensify this practice into pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses) and dharana (intense focus and concentration) as their path of study, svadhyaya, and then to proceed towards sattva guna through dhyana (devotion), and to gunatitan (the state uninfluenced by the gunas) into samadhi, the most profound state of meditiation – through Isvara pranidhana.

By this graded practice, according to the level of the sadhaka, all sadhakas have to touch the purusa (hrdayasparsi), sooner or later through tivra samvega sadhana (I.21).

Hence, kriya yoga sadhana-traya envelopes all the aspects of astanga yoga, each complimenting (puraka) and supplementing (posaka) the others. When sadhana becomes subtle and fine, then tapas, svadhyaya and Isvara pranidhana, work in unison with the eight-petals of astanga yoga, and the sadhanaka’s mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi) and ‘I’ ness or ‘mineness’ (ahamkara) are sublimated. Only then does he become a yogi. In him friendliness, compassion, gladness and oneness (samanata) flows benevolently in body, consciousness and speech to live in beatitude (divya ananda).

This is the way of the practice (sadhana), as explained by Patañjali that lifts even a raw sadhaka to reach ripeness in his sadhana and experience emancipation.

I am indebted to Thorsons for this special edition of Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali, enabling readers to take a dip in sadhana and savour the nectar of immortality.

B.K.S. IYENGAR

14 December 2001