Читать книгу Pacific Seaweeds - Louis Druehl - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

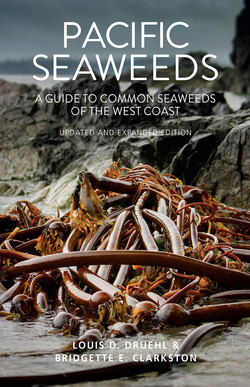

ОглавлениеPacific Seaweeds

26

incompatible or at least sexually isolated. In reality, this sexual criterion is rarely confirmed. Most species recognized today were established on the basis of morphological features prior to our understanding of the significance of interbreeding and sexual isolation. A new twist in defining and distinguishing between species (and higher taxonomic groups) is the application of DNA sequences (e.g., see Biodiversity, the DNA Barcode and the Future of Taxonomy, below). The species name is italicized or underlined. Following the species name are other names (not italicized), which give more information about the species. The “(Linnaeus)” in the species name above tells us that Swedish scientist Carolus Linnaeus was the first to describe this seaweed. He called it Fucus saccharina L. Linnaeus is unique among humans in that he is recognized by the letter L alone. Later, C.E. Lane, C. Mayes, Druehl and G.W. Saunders transferred the species to the genus Saccharina with the species name latissima. “Species” is both singular and plural.

Seaweed names are sometimes presented in this book with single quotes (e.g., ‘R. californica’). These represent species of uncertain taxonomic status: they may be a new species or one already described—more work is needed. Until then, the former name in single quotes is used.

Biodiversity, the DNA Barcode and the Future of Taxonomy

“How many species of seaweeds are there?” is a deceptively simple question we are frequently asked. The answer: many more than we currently know! At the close of 2015 the excellent online database AlgaeBase includes roughly 15,000 seaweed species. This breaks down to roughly 2,000 browns, 6,000 greens and 7,000 reds. Compared to perhaps more familiar groups such as birds (approximately 10,000 species) and mammals (approximately 5,500 species), seaweeds are more diverse. And more mysterious. Scientists predict we will uncover relatively few more birds and only a smattering of new mammals; for seaweeds, we probably have thousands of species left to find.

Identifying seaweeds based on what they look like is difficult, even for experts. Seaweeds have relatively simple bodies—no eyes, flowers, feathers, etc.—and many species have only subtle differences in their appearance. Kelp are the exception, a group of easily identified species, but even here there can be hidden diversity (see Saccharina druehlii, p. 205). Adding to that is the ability of most seaweeds to be “phenotypically plastic”; in other words, the size, shape, number of branches, even colour of an individual