Читать книгу Pacific Seaweeds - Louis Druehl - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

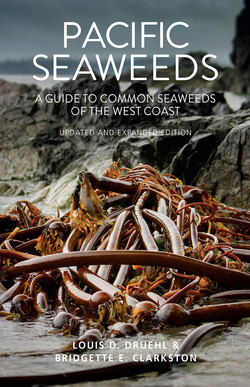

ОглавлениеPacific Seaweeds

28

as it’s growing can be heavily influenced by its environment (see Seaweed Communities, p. 247). Callophyllis edentata (p. 132), for example, might be tall with wide branches in a sheltered cove or short with fewer narrower branches on a wave-swept open coast. Finally, for many species an accurate ID requires knowing the habitat or features of a particular reproductive state. For specimens found washed ashore or those lacking reproductive structures, absolute identification is not possible.

What if you could use DNA to identify organisms and reduce or remove the challenges of morphology? That was the idea of Paul Hebert and colleagues from the University of Guelph when, in 2003, they proposed that DNA could be used to identify most species of animals, plants and fungi. Hebert called it the DNA barcode. The barcode is a short stretch of DNA from a certain gene in the mitochondria of cells (mitochondria are the energy-producing “engines” of our cells and contain their own DNA). Here, instead of the cashier scanning your groceries to find the prices, you could sequence the DNA barcode of an unknown seaweed, check that code against a reference library of all known species and voilà! Identification made. If your specimen doesn’t match a species in the library, then you may have uncovered something new. As of July 2015, this Canadian-driven initiative has generated 4,593,176 sequences for 249,479 species of life. The physical specimens are housed in museums and herbaria around the world, with the DNA barcode library online—Barcode of Life Data (BOLD) Systems—and housed at the University of Guelph.

At the University of New Brunswick, G.W. Saunders and his lab (including BEC during her PhD) have been developing and populating the DNA barcode library with seaweeds since 2004. This work complements Saunders’s career studying the diversity, relationships and evolution of seaweeds around the world. The Saunders Lab has “barcoded” more than 12,000 Canadian seaweed specimens, uncovering dozens of species previously unknown in these waters, and provided invaluable new information about where species are distributed. One such new species is Saccharina druehlii (p. 205), named in honour of LD. Other scientists contributing to this exciting and important work are Patrick Martone, Katy Hind and Sandra Lindstrom (University of British Columbia); Paul Gabrielson (University of North Carolina); Jeff Hughey (Hartnell College); and Kathy Ann Miller (University of California, Berkeley). Many of the taxonomic updates included in this revision are thanks to their efforts, but much work remains before we know the full