Читать книгу Emergency Incident Management Systems - Mark Warnick S., Louis N. Molino Sr - Страница 59

2.5.4 Collaboration

ОглавлениеWhile collaboration is similar to cooperating, it is very different at the same time. Collaboration is the act of uniting with another agency (or agencies) in which they are not immediately connected with. Rather than being a helping hand to another agency, they become a stakeholder in successfully mitigating and ending the incident while working together to create the best possible outcome.

Collaboration, in an incident management sense, is more related to working together, sharing ideas, helping identify resources, and helping to plan the recovery and response to an incident. This is a synchronized and coordinated activity in which different agencies and disciplines continuously work side‐by‐side to develop and sustain the solution for the problem. It can be described as an orchestra with many different instruments coming together for the benefit of the end result.

In the Tokyo sarin attack, there was no collaboration. According to reports, those involved with this incident did not even take other agencies into consideration. Rather than working side‐by‐side, each agency worked independently of the others. As multiple people began to make their way to the subway platform and collapse or sit down waiting for help, only the EMS agency responded to those patients. Law enforcement did not help secure the perimeter, which led to more secondary contaminations. Approximately an hour after the incident started, a news crew took patients to a more distant hospital, they learned that the hospital had not been informed of the incident, and they did not even have a doctor available; they had to summon a doctor to treat these patients. Furthermore, the hospitals did not collaborate, so one hospital was severely overwhelmed while other hospitals saw few patients, or no patients at all (Murakami, 2000).

Essentially, all government levels were operating with little to no cooperation and collaboration between agencies. While it may sound as if this text is repeating itself, you cannot change the facts. Each individual agency did what they thought was best for their small portion of the overall incident, and they did not even consider what might be going on at other areas of the incident or with other agencies. Not only did the responding agencies work independently of each other, but they essentially worked in competition against other agencies. In one report by Pangi (2002), it was found that information was not shared for quite a long time; in one instance related to this attack, information was intentionally withheld for several months. Documentation found by Pangi (2002) revealed that the Self Defense Force (SDF) was still unwilling to share information about the attack with local police for several months, which played a role in slowing the investigation and prosecution of the perpetrators (Pangi, 2002).

Due to the lack of coordination in the Tokyo subway incident, one subway train was allowed to run the entire scheduled route to completion, and then begin the route again with the sarin puddle still on the train. Some commuters affected by the gas laid on the floor for over an hour before a passerby jumped into action (Murakami, 2000). While some of the issues can be blamed on the Japanese culture, it is ultimately first responder's that need to work together, even if it is different than what is normal in their culture.

In Oklahoma City, a collaborative effort was begun almost immediately. At the bombing site, first responders from multiple disciplines worked shoulder to shoulder meeting the needs of the incident. Local resources quickly began to create a unified front of how to best overcome the difficulties they were facing. From the onset, there was no competition between local agencies. They worked together to create the best possible outcome, even though the end of the incident would not be seen for over a month. As was mentioned previously, local and state agencies placed their mobile command centers next to the fire departments mobile command center. These agencies worked together to ensure that nothing was missed and that there was no duplication of efforts. They planned the response together, identifying resources and capabilities, and they worked together and discussed how to best cure each challenge they faced. These local resources were going beyond cooperating by providing resources, and they were collaborating by helping to identify the solutions (Final Report, 1996).

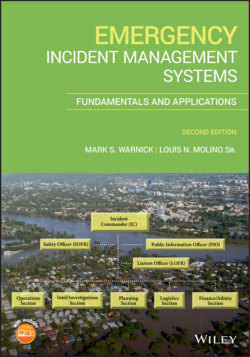

Local businesses and nonprofits collaborated as well. Heavy equipment companies collaborated among themselves and then collaborated with the Incident Commander (IC) and those planning the response. By doing this, the heavy equipment operators helped to ensure safe and effective operations. Local nonprofits went beyond cooperating and worked together with those utilizing the ICS method. Nongovernmental organizations not only helped to identify resources but also to offer solutions to completing the task at hand. These nongovernmental resources worked in concert with all other first responders.

If we look at the Family Care Center, there were multiple agencies that were working side by side rather than independently or in a way that there were clear‐cut duties (Final Report, 1996). Both ends of the spectrum worked to provide care for the surviving family members. The nonprofits, pastors, law enforcement, the funeral directors, the Red Cross, and many more worked tirelessly to meet the needs of the effected families. The mission was more important than the individual organizations involved.

We also need to realize that the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at the state level was activated in the first few minutes after the bombing. Equally impressive was that the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) was fully staffed within 25 minutes. It was staffed by those with the authority to make decisions from a multitude of disciplines. The Emergency Operations Center (EOC) incorporated and worked with the local responders (the boots on the ground), and they incorporated and worked with all levels of government. The Emergency Operations Center (EOC) staff members, all from differing disciplines and agencies, collaborated and worked together to ensure that every need was met at the bombing site and surrounding area (ODCEM, n.d.). The National Guard integrated their resources and collaborated with those in charge as well. Guard members accomplished work by providing security, working in the morgue, digging through evidence with the FBI, and undertaking many other jobs where their assistance was needed. They too collaborated with those leading the effort (Smith, 2010).

The federal response and integration of resources was also a collaborative effort. The federal government did not try to take over the incident, but rather they integrated all of their resources into the response. The Task Force Teams that were deployed to the Oklahoma City bombing site worked in unity with each other and with other agencies. K‐9 teams were integrated with other rescuers, and they worked in a collaborative manner not only with these teams but also with those in charge of the incident. Military resources collaborated and worked side by side with other responding agencies and within the command structure. These resources integrated in a way that went beyond meeting the needs of the response, and they became part of the solution for the entire response.