Читать книгу Master of the Mysteries - Louis Sahagun - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

ON THE EVENING OF MAY 26, 1990, MANLY PALMER HALL, THE 20TH CENTURY’S MOST PROLIFIC WRITER ON ANCIENT PHILOSOPHIES, MYSTICISM AND MAGIC, ENTERED THE IMPOSING SCOTTISH RITE TEMPLE ON WILSHIRE BOULEVARD IN A WHEELCHAIR, LOOKING FRIGHTFULLY PALE AND WEAK. ASSISTANTS LUGGED IN THE WOOD AND VELVET THRONE FROM WHICH HE WOULD DELIVER THE KEYNOTE ADDRESS AT A GATHERING OF MASONIC DIGNITARIES.

The 89-year-old seer was lifted onto the throne. Concerns that he wasn’t up to the task melted away after he rested one hand on the arm of the chair, the other on his wooden cane, and launched into his chosen topic: Freemasonry in the New Millennium. The scene was classic Hall: there he was in the spotlight, flanked by two American flags, at once a philosopher and a master of narration, his blue eyes darting back and forth as though he were reading from an enormous scroll unfurling over the heads of the capacity crowd of four hundred people.

They leaned forward in their seats, hanging on every word as Hall chronicled the mysterious beginnings and mission of the centuries-old fraternity with a sure voice, projecting, in his phrase, “the hope of taking a major step forward. . . in a time of emergency,” with such force one could virtually smell the fire pit of some great castle in the Age of Enlightenment.

“The 21st century has an extreme reminiscence to the 21st year of a person’s life,” Hall told them. “It is a year of coming of age. . . when a person becomes an adult.” Similarly, he continued, in the 21st century, the United States must take on the responsibilities and labors of its own maturity at a time when natural resources were being squandered, politicians were corrupted by power and greed, crime was spiraling out of control, education was failing children, and wars persisted worldwide. Mankind, he said, “has not the right to take a beautiful world with all its privileges and opportunities and turn it into a purgatory.”

“This situation should remind Freemasons that they have something to live for,” he said. “We have the power to build worlds, the wisdom to govern them, and the divine right to inherit the earth and preserve it in good condition in order to pass it on to our descendents as a place of happiness, usefulness and security for thousands of years to come.”

“We’re not asking for treason. We’re not asking for disobedience,” he said. “We’re only asking. . . that in every way possible, when they have the choice, stand for truth and, if necessary, take a little punishment for it.”

From a front-row table with a generous view, Michael Marsellos, a 33rd° Mason and Romanian movie actor, thought to himself, “This is a man of genius. I kept glancing over my shoulders to see how others were responding. Everywhere I looked there were dropped jaws.”

Hall’s 30-minute call to arms was one of his last public appearances in a career spanning nearly seven decades. On August 29, he died under bizarre and suspicious circumstances worthy of Raymond Chandler.

More than a decade later, Hall is still bestowed by adherents with such reverential labels as “Maestro” and “adept.” Much of his life—the magical story of his birth, the whispers of his supernatural powers and membership in secret societies, the dozens of books offering mystical solutions for difficult social problems, the thousands of lectures delivered in a Mayan-style compound nestled between Hollywood and Los Angeles’ Griffith Park, the homicide investigation into his horrible death—fits the image of a holy man hounded to death for the secrets he guarded.

This book tries to get as close as possible to the complex truth about the man and his myth, tracing his rise from a broken family in rural Canada; a chaotic and unhappy childhood; a life-altering dispute with famed escape artist Harry Houdini; stormy marriages; his climb to success in the metropolis that grew up with him; his ties to political bosses and the Hollywood film industry; and his tragic demise.

At the same time, it provides an inside view of the birth of a vibrant subculture in California comprised of mystically inclined artists, visionaries, authors, business and civic leaders who continue to have a profound influence on movies, television, music, books, art and myriad products. Hall was one of its figureheads, making obscure and arcane spiritual texts and symbols of the remote past accessible to everyone just as Los Angeles started to unfold like a desert flower.

It was a time when flamboyant evangelist and faith healer Aimee Semple McPherson attracted more than 5,000 congregants to her Angelus Temple each Sunday, supported campaigns to uphold the nation’s Christian heritage and ban the teaching of evolution in public schools. Hall was not afraid to challenge Christian dogma, and he did it with such poise, scholarship and confidence that thousands followed. In the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s in Los Angeles, many scholars of comparative religion and mythology owed a debt to him.

His longevity sets him apart from the thousands of other mystics and gurus who brought spiritualism to Los Angeles around the turn of the previous century. His writings continue to sell steadily around the world, while collections of his works are being republished for their enduring value and merit.

The widely-traveled Hall wrote quirky, fascinating books and essays illustrated with strange artistic renderings of deities and demons, forces and principles, atoms and solar systems, relics and rituals. They were mostly variations on a theme: clues to solving the mysteries of life were encoded within the symbols, myths and religious rituals of vanished civilizations.

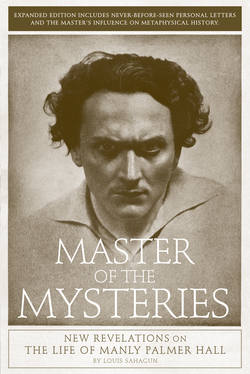

A huge avocado of a man, six feet four inches tall and wide in the center, Hall had piercing blue-gray eyes and chiseled features worthy of a Barrymore. Ardent students of the occult viewed his imposing stage presence and hundreds of books and lectures as signs that he’d tapped into something authentic.

Hall’s was also the most evasive of personalities. He was charismatic, arrogant, scholarly, deeply intuitive, humorous, at times deceptive, and self-destructive—a man who could be startlingly profound one day and disappointingly naïve the next. His favorite pastimes were children’s games: solitaire and Chinese checkers. Onstage, he was bigger than life, seemingly channeling from the great beyond. Offstage, he was meek to the point of being brutalized by his diminutive wife.

Some critics dismiss Hall’s work as biased interpretations of old philosophies and sacred texts by a man who played fast and loose with the facts to prove the validity of magic, spirit manifestations and mind reading. Hall, they also point out, borrowed heavily from the works of others but rarely credited his sources.

They are right, to a point. Hall saw himself not as a scholar, who seeks knowledge for its own sake and the satisfaction of his own mind, but as a teacher who learns in order to bestow his students with knowledge and insight. He did not always practice what he preached, but always directed his teachings along utilitarian lines.

Hall deeply believed in the value of the testimonies of Plato, Buddha, St. Paul and the pagan martyr Hypatia as medicine for the dark side of scientific progress and materialism: pollution, congestion, crime, selfishness, stress and a steady erosion of ethical and moral standards. The same kind of mystical wisdom that awakened and nourished the soul in troubled times of some primordial golden age, he believed, could inspire new generations facing stony walls of conventionalized thinking and commercialized ideas.

His output over more than six decades has rarely been equaled. In more than two hundred books, hundreds of essays and 8,000 public lectures he displayed an astonishing breadth of knowledge of comparative religion, psychology, pagan rites and symbols, classical Greek philosophy, Eastern religions, early Christianity, Freemasonry, Neo-Platonism, mythology, world cultures, and the schools of art and literature they inspired over the centuries. Hall introduced thousands of readers to sages and seers from Francis Bacon to Gandhi who dedicated their lives to helping others attain wisdom.

Long before the Gnostic Gospels were translated into 21st-century bestsellers, Hall was promoting Gnostic beliefs as windows on the origins of Christianity. Before mainstream publications were touting doctors who incorporated a warm and friendly manner into their practice, Hall was urging physicians to also pay closer attention to their patients’ mental and spiritual well-being and offer a handclasp and a smile. Before the advent of blockbuster movies with mythical settings such as Star Wars, Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, Hall co-scripted the first major picture with an astrological plotline and actively encouraged entertainment industry leaders to grow new markets by producing more movies and radio programs based on the spiritual visions and allegories of early civilizations in which sorrow, suffering and loneliness are builders of character. These were not inconsiderable accomplishments for a high school dropout from a broken home in rural Canada.

Hall was a collector of books, stamps, artwork—and good jokes, which he used to spice up his writings and public lectures. His favorites included this quote from Voltaire: “I envy the beasts two things—their ignorance of evil to come, and their ignorance of what is said about them.”

Hall, who rarely laughed out loud out of fear of embarrassment because he tended to wheeze when amused, liked to mimic W.C. Fields to deliver asides such as “Charity not only begins at home, but usually hates to leave the house.” And he was fond of irony. “You know,” he once told a friend, “the Theosophists built a hall for the second coming in Australia. Now it’s a dog track.”

It was all part of Hall’s mission to, as Rex Hutchens, past Grand Master of Arizona and a 33rd° Mason honored with a prestigious Grand Cross, put it, “bring mysticism down to earth.”

“Voltaire said one’s life is not determined by what the church tells you,” Hutchens said. “Breaking bonds with the church sent man on a new path—a path toward perfection of one’s own effort. Freemasonry came out of that. Hall took such ideas and said the same was true of all spiritual quests, which is why he wrote about Buddhism, alchemy, Sufism, Kabbalah and early Christianity. This made Hall seem anti-Christian, but he was born at the turn of the last century and wanted to write intelligent books for rational people about the immense diversity—and interconnections—of spiritual paths.

“Hall was never about truth, which is a childish vanity. He was about seeking truth, which is a spiritual quest,” Hutchens added. “He was a profound thinker and a skilled businessman and he knew what sold. So, on one day he wrote profound insights for those who could perceive them, and the next day he wrote trash for the mass marketplace. He earned a living doing this, and not very many people can.”

I knew none of this when I took a phone call late on September 2, 1990, while working night duty at the Los Angeles Times. “Manly P. Hall, the greatest philosopher of our time, has died,” an excited tipster told me. “You better get an obituary ready.” A few minutes later, I was in the paper’s morgue, sorting through a hefty stack of news clippings about the man dating back to the 1930s.

For much of the 20th century he dazzled the rich and famous, counseled heads of church and state, and lectured at Carnegie Hall and the World’s Fair as a collector and interpreter of ancient texts and symbols as mystical road maps to wisdom, health and longevity.

The founder of the Philosophical Research Society, a school of enduring wisdom teachings Hall established on Los Feliz Boulevard, was frequently quoted opining on the hottest topics and fads of the day: World War II, Zen Buddhism, space travel, unidentified flying objects and prospects for peace in the atomic age. Portions of his vast collection of books, artifacts and rare stamps accumulated from around the world were often loaned for display in city and county libraries, schools and department stores across the state. Hall was a frequent guest lecturer at universities and private colleges on the subject of comparative religion.

I was fighting a tight deadline and the paper had room for a brief obituary, which began, “Manly Palmer Hall, an eclectic philosopher and founder of the Philosophical Research Society, has died at 89, the society reported Sunday. The peripatetic philosopher, who authored more than two hundred books and gave more than 8,000 lectures—many of them from a throne-like chair at the society’s Los Angeles headquarters—died in his sleep Wednesday of natural causes, a spokesman said. The death had been kept private for 72 hours at the request of his wife, Marie Hall. ‘His wife said the silence had to do with his religious beliefs,’ said Daniel Fritz, a trustee of the nonprofit educational society founded in 1934.”

The obit lacked important information that was unavailable on deadline. How did Hall become a venerated expert on spiritual beliefs, philosophical principles and symbols? Where did the money come from to pay for his world travels and a treasure trove of artifacts and books? How relevant are his works in modern society? Exactly how did Hall die? Like everything else about Hall, the answers are complicated.

Gathering facts was not easy. Hall was never forthcoming when it came to details about his personal life or his credentials. Many of his closest associates had died decades earlier. The theories Hall promoted are subject to interpretation.

With a goal of letting Hall speak for himself, I have relied heavily on his essays, books, memoirs and unpublished letters, as well as court records, testimonies and interviews with his widow, stepchildren, friends and associates around the world, homicide investigators, coroner’s officials, defenders and detractors.

Hall’s was an extraordinary life, one entwined with the original idealists of formative Southern California at the dawn of the 20th century and Los Angeles, the city that nourished them.

He’d come to California in 1919 to be reunited with his mother, who had abandoned him in infancy. The 18-year-old Canadian immigrant—who had bounced from town to town as a child with his maternal grandmother, the peripatetic Florence Palmer—turned his back on a business career in New York City’s Wall Street after she died suddenly.

Within a decade, Hall would take over a prominent Los Angeles church and then transform himself into a world-renowned philosopher and student of the occult—the hidden mysteries of the universe, of life and of death—in a place that was mushrooming into one of the most promising metropolises on the planet. Public fascination with magic, healing arts and “the other side” of life flourished in the 1920s. As if drawn by a magnetic field, others not unlike Hall came to the city: earnest seekers and enthusiasts, utopians, mystics, spiritualists, gurus, healers, quacks and cranks of every stripe.

In 1928, at the age of 27, Hall published his magnum opus, an introduction to ancient symbols and secret traditions called An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy. Chapters of the lavishly published book, also known as The Secret Teachings of All Ages, open like portals into parallel universes. The diction is simple and strong, and punctuated with many lines taken directly from sources as old as the Pentateuch of the Bible and The Divine Pymander concerning Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus. This immense book is filled with strange, often disturbing illustrations, and uses Roman numerals instead of standard page numbers.

Publication of Hall’s so-called Big Book initiated a new era of appreciation for ancient religions and symbols and catapulted him to the top of the list of America’s scholars of mysticism and magic. He also gathered many acolytes, some of them trust funders of an earlier age seeking purpose in a world where their every whim had been fulfilled with little effort or thought. A mother and daughter belonging to the Lloyd family, an oil dynasty of Ventura County, over the years would donate millions of dollars to Hall’s projects. They helped underwrite his whirlwind tour of the world’s centers of spiritual thought in 1923 and eventually helped establish his compound near Griffith Park in 1934.

When some groups pitched elaborate schemes promising to share divine secrets for a fee, authorities began to take notice. Eager to separate himself from the riff-raff of spiritualists, Hall worked briefly in 1939 as the eyes and ears of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office when it wanted to topple a cult known as Mankind United, believed to be bilking members of their worldly possessions.

Throughout the 1930s, he lectured from coast to coast, attending dinner fundraisers with influential people including Robert Andrews Millikan, chairman of the executive council of the California Institute of Technology, and legendary motion picture director Cecil B. DeMille. In 1938, he scripted an occult murder mystery for Warner Brothers titled When Were You Born? In 1940, he delivered a lecture at the New York World’s Fair on the contributions of ancient Greece. Hall was enjoying the most successful period of his life. Still, a devastating personal crisis was falling into place at home. In 1941, his first wife, the sultry Fay Bernice Hall, committed suicide.

During World War II, Hall, a patriot to the core, tried to rally hope by drawing on obscure Masonic writings, fragments of Egyptian religious teachings and utopian fables by the likes of Sir Thomas More to suggest that the creation of the United States was part of a great experiment launched by leaders of an ancient league of nations to develop a philosophic empire. Thousands of years before Jesus, he said, they had charged the Western Hemisphere with special spiritual, mental and emotional forces. Evidence of what he called the “secret destiny of America” was first seen in the advanced civilizations of the Aztecs and Mayans, as well as the democratic systems and reverence for nature demonstrated by Native American cultures. With the nation on a war footing, the plan now required that America accept the challenge of leadership and establish “a new order of world ethics firmly established on a foundation of democratic idealism.”

By then Hall had delivered thousands of lectures and published dozens of books on the teachings of sacred thinkers and basic principles of wisdom teachings he felt were potent and timeless. His readers came to view his works as instruction manuals for harmonizing with the inflexible laws of the universe, laws that guide the motion of planets and human evolution, even the destiny of the nation.

President Harry Truman had Hall’s books on his shelves. California Lt. Governor Goodwin Knight was a trustee of Hall’s society, and influential Los Angeles politician Sam Yorty touted him as a valued citizen. Movie stars Bela Lugosi, Lew Ayres and Gloria Swanson were close friends.

But times were changing. By the late 1950s, some thought Hall’s archaic ideals were out of step with materialistic progress, and the world had started to drift away from him. When some of Hall’s concepts about early civilizations and the origins of religion were judged by modern archeological and anthropological standards, their flaws seemed glaring. Everything modern, bright and shiny as a new car had promise. Everything old suddenly seemed quaint, or useless. His ancient spiritual ideals did not seem to mitigate the anxiety and fear that accompanied the advent of weapons of mass destruction.

Hall stood firm, insisting that science couldn’t fathom purposes or meanings of qualities of spirit; that courage and bravery can change the outcome of possibilities on the battlefield, in the laboratory or in the workaday world of the average family.

Doubting the supremacy of scientific breakthroughs and updated interpretations of philosophy, religion and history, he all but stopped buying new volumes for his fabled library. He chastised rock ‘n’ roll, jazz and modern art as potentially dangerous cacophony and watched arguably less talented peers such as Ernest Holmes, founder of the First Church of Religious Science, develop far larger metaphysical denominations.

Hall’s warnings around this time of an impending “great decision” that would involve Western powers and Islamic nations could come straight from an early 21st-century news report. The great problem that faces the world, he forecasted in a lecture, centered in the area of the Eastern Mediterranean. “This center of tension,” he said, “is probably more important than at first appears and will justify our thoughtfulness concerning the Mediterranean area, which is part of the world policy.”

Amid the Utopian wonderment and experimentation of the 1960s and ’70s, Hall’s Hollywood compound attracted a new generation of people from surprisingly diverse fields and disciplines, from Burl Ives to astronaut Edgar Mitchell to Elvis. However, in a time of sexual liberation, mind-expanding drugs and hippie counterculture, Hall seemed strange, stuffy, and demanding to others, and, judging from his physical appearance, embarrassingly out of step with his own advice about the importance of self-discipline with diet and exercise.

By the 1980s, Hall knew all too well that his inconsistencies and personal failings were catching up with him and disappointing some acolytes. He had predicted that would happen in essays written decades earlier on the dangers of putting spiritual leaders on a pedestal.

“One cause of disillusionment in metaphysics is for the metaphysical teacher to prove to be more human than originally suspected,” he wrote in an essay published in 1942. “The tendency is to so elevate personalities that we endow them with sacred powers. All our faith is put upon them as we hang tinsel on a Christmas tree. The leader is assumed to be infallible, whereas he is no more than one who is well-meaning, quite capable of contributing to the improvement of humanity, but still personally subject to innumerable ills. Doing the best he can, he is a good human being but a poor divinity. All followers who offer to adorn and deify their teachers set up a false condition. Human beings, experience has proved, make better humans than they do gods. We should be willing to accept a person who possesses wisdom as a friend, not deify him; it just won’t hold up.”

A year later he wrote, “Why did the disciples of Pythagoras always refer to the master as ‘The Man,’ as in the Bible we are enjoined to ‘Behold the Man.’ Why? Because in the old mysteries only the initiated were human—the rest were trying to get that way, and any greatness was measured by their accomplishment. Only the great initiated adepts were recognized as human; the rest were creatures crawling toward the light who, having eyes, see not, and are therefore blind; who, having ears, do not hear. It is in this manner that the Platonist tells us what they were trying to do at our stage of human development; not to make gods out of men, but to make men out of beasts, and so lift humanity up to its true estate of enlightened harmlessness, where men no longer prey upon each other.”

He could have been talking about himself. Although he saw the validity of sacred truths, he was also swept away by questionable enthusiasms that were profitable and popular, like mental telepathy and the healing powers of gemstones. He could distill the salient principles of Neo-Platonism, but he enjoyed being the center of attention, and didn’t trust anyone but himself.

For much of his life, Hall binged on cheap sweets such as donuts and malted milk balls, avoided physical activity, and sometimes cultivated relationships with followers by telling them, for example, that they had been close friends in a past life, or that secret societies had big plans for them. Putting himself in the role of a godlike man who could not be questioned opened the doors for idolatry and abuse.

On August 23, 1990, Hall’s caretaker, executive officer and confidant, Daniel Fritz, who billed himself as a shaman and expert in alternative medical techniques, rushed to the ailing philosopher’s office in order to resolve an urgent legal matter. He needed Hall’s signature on a new will and living trust arrangement. It would help Hall’s survivors avoid probate. After Hall died, control over the Philosophical Research Society, the compound and its contents, then valued at about $5 million, would go to the successor trustee, Fritz.

And why not? The old man had neglected the place for years. Buildings were in desperate need of repairs. The copyright on some of his writings had been allowed to lapse. His personal library of 30,000 volumes lacked even fire alarms to protect them. Valuables, including gold coins, were inexplicably missing from his walk-in vault. And Hall, who was beginning to show signs of senility, had yet to groom anyone to succeed him.

Clearly, he told him, something must be done quickly. Hall agreed, and with a few strokes of his pen, he signed documents that essentially turned over his assets to Fritz, wedging out his second wife, Marie, and stepchildren who were to inherit everything, according to the last will and testament he had signed nearly two decades earlier.

Six days later, on the morning of August 29, Fritz telephoned a local mortuary to report that his boss had died in bed of natural causes. The corpse collectors and the Halls’ family physician were alarmed by what they saw in the bedroom.

Hall’s immense pale body lay on a bed without a single wrinkle; thousands of ants streamed from his ears, nose and mouth. A cleaning crew was attacking reddish-brown stains on the carpet near the bed. Fritz and his helpers were busily carting Hall’s clothes and valuables from the home to his car. The physician, growing increasingly suspicious, rescinded the death certificate he had signed a few hours earlier.

Fritz insisted that his boss died peacefully in his sleep. Los Angeles Police Department investigators have a different theory: that Fritz murdered Hall.

The case remains an open-ended Hollywood murder mystery.