Читать книгу Master of the Mysteries - Louis Sahagun - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

City of Angels

IN THE EARLY 1900S, IT WAS EASY TO IMAGINE THE SUNNY CANVAS OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA AS A SORT OF PARADISE: A PLACE OF SPARKLING BEACHES AND IRISH-GREEN HILLS, VINEYARDS AND FRAGRANT ORANGE BLOSSOMS; A WESTERN OUTPOST EXPLODING WITH POSSIBILITIES AS A HOME TO THE FLEDGLING MOVIE INDUSTRY AND MYRIAD FRONTIER RELIGIONS. FABULOUS OIL WELLS WERE BEING STRUCK AND FERTILE VALLEY FARMLANDS ROLLED OUT LIKE CARPETS.

A place of adventure and change was not what Manly Palmer Hall was looking for when he stepped off a train in downtown Los Angeles in the fall of 1919. For Hall, the lure of Southern California was the chance to reunite with his mother, who had abandoned him in infancy. The 18-year-old Canadian immigrant, who never knew his father, had spent a confused and insecure childhood bouncing from town to town with his maternal grandmother, Florence Palmer. They had been living in New York City when she died suddenly, leaving Hall with little choice but to quit his clerk’s job at a Wall Street firm, leave the city, and move into his mother’s home in the beachside community of Santa Monica. [1]

Louise Hall, who had worked for 15 years as a chiropractic healer in the Alaskan gold fields, shared the modest house with her second husband, Charles Hall, a jack-of-all-trades who took her last name. [2]

If there were hard feelings between Hall and his mother, he never spoke of them; that is, beyond gentle chiding for burdening him with an odd name. As for the father he never knew, Hall would only say that husbands who walk away from their families are irresponsible and inconsiderate men who antagonize their wives, polarize relatives and plague their children with lifelong “negative uncertainties.” [3] If anything, Hall thrived in his new home and soon shared his mother’s fascination with the emergence of utopian religious communities—from Ojai south to San Diego—all hoping to set the stage for a better way of life.

Hall believed he was witnessing a westward expansion of visionaries and seekers into a territory laden with gold and oil and rich with potential to be the birthplace of a spiritual revolution. The Midwest and East Coast of the United States were sedentary landscapes inhabited by people for whom a pioneering spirit was a thing of the past. The wide open spaces of California, however, were ruled by astrological fire signs of courage and action: Leo, Aries and Sagittarius. In this greenhouse of ambitious immigrants and freethinkers, Rosicrucians, Vedantists, Freemasons, Theosophists and fringe Christians were already changing the landscape with striking meditation gardens, ashrams, temples, occult lodges and churches.

If there was any place in the United States in which ancient wisdom would emerge and flourish it was here in the spiritual melting pot of Southern California. As Philip Jenkins writes in his Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History, “Some of the new movements contributed to the cultural and economic development of the growing city of Los Angeles: in a sense Hollywood is built on occult foundations.” [4]

Hall enjoyed exploring Santa Monica’s seaside restaurants, shooting galleries and fun houses and fortune-tellers’ booths. One day, he noticed a store sign advertising “phrenology,” the pseudo-science popular at the turn of the 20th century that divided the brain into areas responsible for noble traits such as heroism and despised ones such as cruelty. Stepping closer to the window, he studied a grid map of the surface of the brain. Through the glass, he could see anatomical charts tacked onto a wall inside.

Curious, he ventured into the strange little studio presided over by Sydney J. Brownson, a diminutive horse-and-buggy doctor and Civil War veteran in his early seventies with a sweet smiling face, shoulder-length white hair, a full beard and thick spectacles. Hall casually asked, “Perhaps you would like to read my bumps.” [5]

Brownson winced and sternly replied that phrenologists do not read bumps; they make “calculations by measuring the radial length of brain fibers from the pons of the medulla oblongata.” Then he regaled the tall young man for hours about human auras, the magnetic fields of the human body, and reincarnation.

Hall was as enthralled by Brownson’s metaphysical topics as by the older man’s optimism and certainty of the human condition. Brownson was a private person and seldom discussed his personal life. But, taking a shine to his wide-eyed customer, Brownson told Hall that his life had been transformed by a mystical vision and a calling he received at the end of a Civil War battle that lasted all day and into the night.

Brownson also confided that he was having marital problems.

When Hall asked if he married the wrong woman, Brownson energetically replied he would gladly do it again if the choice were his because “we live in this world to learn, and I learned from her more about women than I ever thought there was to know.”

Nearly two decades later, Hall would remember those words as a sneak preview of his own struggles at home.

“All things work out well in the end,” Brownson assured him, and then cryptically added, “God does not make failures, but sometimes the Golden Age seems to be indefinitely postponed. But it will come when folks have stomachs as empty as their heads are now.” [6]

Brownson saw the makings of a capable apprentice in his young friend’s exuberant curiosity, his photographic memory and persuasive intellect, and his burning desire to explore the secret teachings of vanished societies. Tall and handsome with black hair and a debonair mustache, Hall was also a confident speaker, rather like Brownson himself at his age, only better.

The two began an intense mentor/student relationship that changed the way Hall thought about life. He was drawn deeper and deeper into the old man’s teachings of lost and hidden traditions, the golden verses of Hindu gods, Greek philosophers and Christian mystics, and the spiritual treasures waiting to be found within one’s own soul.

Less than a year later, Brownson invited Hall to speak to a half-dozen free spirits who gathered weekly in a room above a Santa Monica bank. Hall’s topic that afternoon in 1919 was his new obsession—reincarnation.

The audience of eight mostly elderly women showed their appreciation with offerings that totaled 65 cents. The philosophers—one five feet tall and weighing about 120 pounds, the other six feet four inches tall and on the heavy side—then splurged on chocolate sundaes at a drugstore down the street. [7]

A few weeks later, Hall and Brownson took the Big Red streetcar from Santa Monica to the corner of Fourth and Hill Streets in downtown Los Angeles, where Mrs. Eleanor Reisberg managed a metaphysical lending library and a small lecture hall used by religious seekers. Reisberg’s guest speakers were allotted various hours based on the size of their anticipated audience. It was generally agreed that the 6 p.m. dinner hour was the least attractive time slot. [8]

And so the untested Hall gave his first real lecture on the mysteries of life at 6:15 p.m. The few dozen listeners of mostly new Californians offered up a total of $1.65, a substantial take at the time. Within weeks, he drew audiences large enough to command the preferred 8 p.m. hour.

After years of living without fixed points or a real family, the universe was going his way. He believed deeply in the arcane notions he spoke of at the lectern even if no one outside his tiny group of listeners did. Moreover, his mother swelled with pride over his improbable new career: a spiritual version of the California dream.

Hall immersed himself in ancient myths and religious doctrines and punched up his lectures with current events and humorous asides. Gradually, by trial and error, Hall was developing an inspiring message and delivery.

Hall believed in the remote past there was a core religious belief—the universe was a manifestation of an invisible creating principle, which can conveniently be called God—that had been deliberately hidden in the symbols, myths and rites of the world’s oldest societies. For a Hindu, that meant the universe and he or she are one. For a Muslim, God is as close as his jugular vein. Christians find Christ in their hearts; in essence, the search for God lies within. [9] [10]

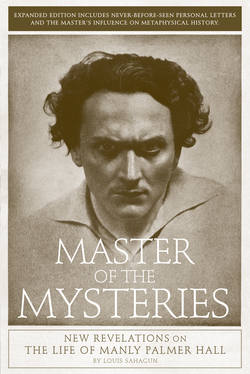

Hall c. 1920

His sources ranged from Egyptian religion to the lives of Christian saints, and from classical Greek philosophy to the writings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a Russian mystic who claimed contact with ascendant masters whose wisdom shepherded the divine plan.

The universe, he proposed, is a living, expanding entity of eternal laws. The simplest way to study these eternal laws of existence was to observe the consequences of conduct. When we overindulge, we get ill. When we manage our desires, we are not ill. When we spend more than we earn, we are burdened with debt. When we neglect children, they turn against us. When we are critical, we lose friends. Therefore, Hall concluded, the answer to man’s spiritual needs is self-discipline stemming from ideas that “impel the believer to remake his own life, correct his faults, strengthen his character, and deepen his knowledge.” Moreover, he proposed, nature, out of her infinite capacity, brings forth at various times and places exemplary souls dedicated to passing this great secret of life on to future generations. [11]

Hall, his listeners assumed, was such a one.

Hall concluded his lectures—which typically took 90 minutes and were delivered without notes or a break for so much as a sip of water—with homespun common sense about modern living drawn from the spiritual beacons of all ages and cultures he had gleaned from occult books he owned, borrowed, or had checked out from the Los Angeles Public Library.

People were impressed by Hall’s confidence, his knowledge and extraordinary physical stature, a tall silver-tongued orator who carried himself with a distinct air of superiority.

In late 1919, Hall was invited to address one of the most progressive religious forums in the city, the Church of the People, which met on Sunday mornings at the Blanchard Hall Building in downtown Los Angeles and followed up with lunch at Clifton’s Cafeteria on Broadway. [12]

The church and its fellowship were founded by the broad-minded evangelist Benjamin Fay Mills, who had become a student of the transcendental philosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau and the practical idealism of American psychologist and philosopher William James.

Mills was a liberal, energetic and brash preacher. His motto: “If I can’t do it, and my wife can’t do it, and the children can’t do it, it can’t be done.”

Eventually, however, Mills lost faith in the transcendental ideals he had championed for years, reverted to the Presbyterian faith and left town. In his place stepped Los Angeles accountant Reynold E. Blight, a gifted speaker who stood less than five feet tall and had to buy his suits in the children’s sections of department stores. Blight, a 33rd° Mason and student of comparative religion, became a bigger draw than Mills. He brightened the services with musical soloists and strengthened them with lectures on Greek philosophy and politics.

When Blight took a sudden leave of absence, Hall, who had been a regular member of the audience, became temporary pastor of the church’s eccentric six-hundred-member congregation. Among its members were populists, intellectual socialists, utopians, single-tax enthusiasts, vegetarians, and young drifters seeking direction in life. “It takes a crank to make the world go ’round,” his congregants liked to say around this time. [13]

Blight never returned to the pulpit. With Hall assuming increasing responsibility, the little church began to downplay political panaceas and emphasize practical philosophy. Hall charged a dollar to attend his Sunday lectures, a set fee that continued all his life.

One adoring member of the congregation, an elderly Scotswoman, presented the young preacher with a rare and elegant four-volume 19th-century set entitled The Works of Jacob Behmen (Boehme). It was the start of a collection of rare and unusual books that would eventually to grow to 30,000 volumes. [14]

Hall was enchanted by the woman’s curious personal life: she lived in an old-fashioned wood frame house, wore heirloom dresses, and kept a second place setting and the most comfortable chair reserved at her dinner table for an “unseen guest” who might be the presence of Christ one day, and the spirit of her long dead husband on another. [15]

Hall had no experience whatsoever in running a church—or anything else. But the 19-year-old was naïve and enthusiastic enough to take on the duties, which included counseling in a small office people old enough to be his grandparents. [16]

“This is something that has to happen to you before you can fully appreciate it,” he said years later. “Factually, I had little to offer them. I had not solved any problems of my own. I didn’t know exactly why I was leading a church, but it was one of those accidents or circumstances of fortune that you do not question. [17]

“So when these people came to me with their problems, I sat back with the supreme wisdom of a teenager and told them what I thought common sense would dictate, what seemed to me reasonable. And it worked in many cases.” [18]

Peppered with a wide variety of personal questions from people seeking immediate answers, Hall began boning up on comparative religion, philosophy, sociology and psychology. He reported back with the warm, reassuring words and admonishments of Confucius or some other sage. Seemingly overnight, Hall became a one-stop source of an astonishing range of eclectic spiritual material that resonated with the intellect, and the subconscious.

Los Angeles, c. 1915

It was a time when many civic and business leaders, judges, architects, physicians, engineers and entertainment industry figures were members of Masonic lodges, whose Neoclassical temples were among the most imposing buildings on the Southern California landscape. Among them was developer Charles E. Toberman, often referred to as the “father of Hollywood.’” Al Ridenour, in a May 2002 Los Angeles Times article, wrote, “Master of the Hollywood Lodge in 1914, Toberman was not only responsible for enticing Sid Grauman into Hollywood to create the Egyptian, Chinese and El Capitan theaters, but also for construction of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, Hollywood Bowl, Pantages Theater and Max Factor Building. Before any of these developments stood along the boulevard, however, Toberman built the new lodge headquarters there, in 1922. At the time, the temple was one of the most substantial structures in Hollywood’s sparse mix of buildings and citrus groves. [19]

“In those days when Hollywood was an independent city, the city attorney, city marshal, city treasurer and first mayor, George Dunlop, all were Masons,” Ridenour wrote. “Arthur Letts, founder of the Broadway department store, and artist Paul de Longpre, whose gallery and gardens drew many to the community, both were members along with prominent judges and a significant number of bankers. The city’s first newspaper and doctor’s office were established by members, and the city’s electric trolley car service was owned and operated by brothers of the lodge.” [20]

Hall hoped to catch their attention.

As a gateway into the world of ancient religions, Hall encouraged his congregants to explore Theosophy, a philosophical system founded in the late 1800s by Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky that embraced notions of reincarnation, karma, the cyclic nature of creation and the interconnectedness of all life. According to Blavatsky, this Wisdom, in its pure form, existed before the dawn of civilization, but was given to and understood by only a handful of initiates and great minds throughout the ages.

“It was Blavatsky’s contention that the Wisdom could be partially recoverable from a ‘comparative study and analyses of selected philosophers,’” wrote James Santucci, a professor of religious studies and linguistics at California State University, Fullerton, in his A Brief Overview of Theosophy.

By those Blavatsky meant Pythagoras, Plato, Plotinus, Proclus, or schools of philosophies such as Neo-Platonism, Vedanta, Taoism, Kabbalah and the sacred writings of Christianity, Buddhism, Islam and Hinduism.

“A study of these philosophers, schools and religions by Blavatsky,” Santucci wrote, “under the guidance of two Masters of this Ancient Wisdom—one usually identified by the initials K.H. (Koot Hoomi), the other by the initial M. (Morya)—led to the writing of her two great works, Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine, works that partially revealed the Ancient Wisdom in a modern form.”

Her Theosophical Society’s mission included investigating higher powers she believed were innate in man, and teaching that everything in the universe, even human souls, races and nations are subject to progressive and cyclical evolutionary development.

One of the most prolific writers within the broader Theosophical movement was Max Heindel, a Christian mystic and German immigrant who established a spiritual commune in 1907 on a scenic bluff called Mt. Ecclesia in Oceanside, about 80 miles south of Los Angeles. Heindel subscribed to a mystical interpretation of human evolution that placed blacks and Jews behind Anglo-Saxons. Such views hardly raised an eyebrow among California’s new immigrants, most of whom were white like Hall and much of the rest of the country at the time. [21]

Dedicated to Jesus, astrology, the power of prayer and providing an explanation for the origin, evolution and future development of the world and man, Heindel’s Rosicrucian Fellowship soon became a favorite vacation spot for young Hall and his mother.

Their first trip to Mt. Ecclesia was in 1920, a year after Heindel’s death. [22] His widow, Augusta, was struck by Manly’s talent as a writer, his youthful pastoral work at the Church of the People, his graciousness and his intense interest in her husband’s complex books, which essentially taught that Earth is a great school to which ever-evolving individuals come by way of reincarnation, life after life.

At Mt. Ecclesia, Hall grew so attached to Heindel’s temperamental heavy-set widow that he started calling her “mother.” She and her followers taught him astrology and the fundamentals of typesetting, printing and binding. From them, he also learned to avoid writing in longhand with an ink pen because it siphoned off one’s vitality, an admonishment he obeyed for most of his life, preferring instead to dictate his books. He showed her how to play backgammon, and was her connection to prospective younger converts. Together, they wrote numerous articles for the fellowship’s newsletter, Rays from the Rosy Cross, which compared life on the bluff to heaven on Earth.

“Why does this spot seem so beautiful?” Hall wrote under the title “Echoes from Mt. Ecclesia” in mid-1921. “There are many other places where the stars may be seen and studied, and thousands of people see the same glorious sunsets, and enjoy the same wonderful climate. But there is something here that is not to be found in any other part of the world. There is something here that is restful and different; it seems almost like holy ground. It is because of the love that is sent here by thousands of members and the lives of self-forgetting service that the workers are living day by day, that makes this the beauty spot of the earth.” [23]

Mrs. Heindel would become distressed by Hall’s active interest in hypnotism, which she considered one of the “black arts.” [24] None of that, however, reached the ears of Hall’s own Los Angeles congregation, which regarded his ties to the Rosicrucian Fellowship and its founder’s widow as impressive spiritual credentials.

Hall’s cross necklace

The mainstream press responded to the first of California’s seekers with articles that were by turns tolerant and skeptical of the modern spiritual urges and metaphysical forces. Some perceived them to be undermining traditional faiths.

On March 18, 1922, the day Hall turned 21, the Los Angeles Times’ front page featured a story about a Philadelphia psychologist who had proved that an episode of spirit knockings and ghostly visions had been a fraud. Yet, inside the same issue, the religion page carried advertisements by the United Lodge of Theosophists, which had scheduled a lecture on “states after death,” and Hall’s Church of the People, which offered a talk called “The Religion of H.G. Wells.”

A few months later, The Times printed a front-page story about a trend-setting “all-night psychic pharmacy” in Chicago operated by three shifts of “love healers,” a lengthy book review of Maurice Maeterlinck’s compendium of enduring doctrines titled The Great Secret, and an above-the-fold news column called “Your Hidden Powers,” which claimed, “There is a purpose in every man. In each there is a seed, the seed of the soul. . . We water it with sweat and tears, around it we fertilize it with our agonies, our joys and our struggles. . . and we are not unaided. Nature helps us. In the conscience of every man there is a guidance.”

Hall entranced his Church of the People audiences with folksy interpretations of Pythagoras, Confucius, Lao-Tsu, Buddha, Plato, Jesus Christ, St. Paul, Moses ben Maimonides, St. Thomas Aquinas, Immanuel Kant, Baron Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz, William James, and Herbert Spencer, as well as of such obscure 19th-century writers on the occult as Albert Churchward, Arthur Dyott Thomson, Charles William Heckethorn and Arthur Edward Waite. The turn-of-the-century works of Irish biblical archeologist Elizabeth Anna Gordon inspired lectures on the religious traditions of Japan.

“It soon became clear,” Hall wrote years later, “that almost every problem brought to me in the course of a day or a month or a year had been handled by someone long ago. . . So it was very much safer for a novice like me to quote somebody who seemed to know, than to quote myself and realize that I didn’t know. For me it was just guesswork, but Confucius had worked it out.”

On March 17, 1923, Hall was ordained a minister in the Church of the People. [25] A few days later, he was elected permanent pastor of the church, and the congregation honored him with a Rosicrucian-style cross that was based on a design of his own and made of diamonds, platinum, gold and white enamel. Etched with emblems and symbols of astrology and ancient religious schools, it represented the ideals shared by all spiritual quests. Dangling from a chain around his neck, Hall proudly wore the flashy fist-sized cross as a symbol of spiritual authority in a state where alternative spiritual movements were becoming significant cultural forces.

The belief in reincarnation had become especially popular. One day around this time, Hall met an old chum on the street and noticed a large book under his arm. “What are you reading today?” Hall asked. With a twinkle in his eye, Hall’s friend answered, “First-year Spanish. I don’t expect to learn much of the language now, but I figure it will be more popular when I come back next time, so I might as well get a little start.”

Even flamboyant holy roller Aimie Semple MacPherson, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1918, was milquetoast compared to others setting up religious shops in town.

Hall kept track of the competition by collecting the advertisements they posted in local newspapers and magazines.

Dr. Nephi Cottam pitched “the great discovery of the new age, Craniopathy.” Manneck of India promised “triumph through the wheels of adversity.” Mystic Edwin J. Dingle, founder of the still-active Institute for Mentalphysics in the desert community of Joshua Tree, exhorted, “you, too, can have lots of pull!”

Charles Robert Wilson concluded his lectures on “esoteric meditation” with astrological forecasts for the week to come. The National Academy of Metaphysics offered courses on “ancient teachings modernized.”

Crystal-gazer Princess Zoraida, smiling seductively under a turban studded with rhinestones and baubles, taught the “cult of Ptah.” Pneumandros, a spiritualist who called himself “The Spirit Man,” offered a $5,000 reward to anyone who could prove his healing powers were fraudulent. Pyramidologist Prof. J.W. Parker claimed to have proof that the Great Pyramid of Egypt was “the Bible in stone.”

George Terry billed himself as the “pre-ordained, foreordained, predestinated Prince of Destiny, luminary mandate of imperial pre-eminence, Israel, seventh son of Melchizedek, hierophant of the universe.”

Then there was Hall’s friend, Count Louis Harmon, better known in his day as “Cheiro,” who believed a person’s character is revealed in the lines of the palms and feet, and in the general shape of the hand, foot and toes. Cheiro, who owned two newspapers, was a tall, handsome, beefy man with influential friends, a cheery smile, a rich Irish brogue, and a reputation for entertaining extravagantly. Among those Cheiro claimed sought his private counsel to get clearer insights into their futures were England’s Edward VII, Samuel Goldwyn, Oscar Wilde, poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox and actress Mary Pickford. Madame Blavatsky wanted him to join her Theosophical Society, he bragged. [26]

Cheiro, who died at age 70 in Hollywood, cast the horoscopes of nations and issued predictions, many of which later proved wildly off-base. He predicted a “war of wars” would break out around 1940 “when Israelites and their coworkers in Palestine open up Egypt, with its vast resources.” This, he said, “would arouse antagonism from the followers of Islam, and Turkey, backed by Russia, will endeavor to recapture Palestine.” [27]

Germany and England, he said, would eventually become allies and pour immense numbers of troops into Palestine and Egypt against Russia and Turkey.

Self-taught practical philosopher Ernest Holmes represented a Los Angeles-based religious empire spawned by his own wholesome brand of positive thinking for success on Earth and the hereafter.

Elsewhere in California, Theosophist Katherine Tingley was the “Purple Mother” of a community of three hundred residents at the Point Loma promontory west of San Diego. H. Spencer Lewis of New Jersey helped establish the Ancient and Mystical Order of the Rosy Cross center in San Jose, where some initiates tried to turn lead into gold in elaborate alchemical laboratories.

The New Thought faith healing movement, borne in the late 19th century, spun off dozens of influential ministries that mixed traditional Christian religion with metaphysical principles. It taught the use of positive affirmations: If you want to be rich, you need only to think rich. If you want to be beautiful you should realize you already are and just haven’t noticed it yet.

Frederick Bailes, in his book Hidden Powers for Human Problems, promised “with complete faith, I can make this statement: If you practice the principles of the creative process as set forth in the following pages you will see and feel a new force in your life within seven days.” [28] Anthony Norvell claimed to have personally “investigated the lives of geniuses, millionaires, titans of industry, writers, composers, bankers, financiers, actors and producers to come up with the million-dollar secret,” available for a small gift of love at the lectures he gave at rented movie theaters across the city. Similarly, Neville Goddard, who always appeared on stage wearing pure white suits, taught thousands of followers in Los Angeles “the miracle of imagination.” Trouble is, Hall wryly noted, “Everyone thought rich, and teachers of the doctrine prospered.” [29]

“Self-appointed teachers arose without adequate backgrounds, knowledge, or credentials, and swept through the nation,” Hall wrote years later. “It is entirely wrong to assume that this was a West Coast phenomenon. It was distributed throughout the country, affecting all of the larger metropolitan areas. Glamorous ladies in thousand-dollar evening gowns, waving ostrich-plumed fans, taught prosperity to the hungry and poor at $25 a course, and those with adequate promotion counted their profits in the millions every year. Mysterious swamis, yogis, and the like, entranced audiences of from 2,000 to 4,000 at a meeting, and these were followed by food experts who draped the façades of our larger auditoriums with garlands of raw vegetables.” [30]

Hall knew them all. But unlike some competitors, who he felt were selling dubious shortcuts to peace, power and plenty during the swinging 1920s, he wanted to be known as a philosopher and a shaper of a new world, one that would guide the nation through the “dark years” that he predicted “lie ahead.”

“We need holy men and women,” Hall wrote, “to assist in the establishment of higher standards of right and wrong; to amend unjust laws on our statute books; to become the patrons of broader and nobler educational ideals; to foster the cause of world peace; to aid in the achievement of economic justice; and, most of all, to provide the millions of this generation with a workable, livable philosophy of life.”

Hall’s writings at the time reflect the vibrant spirit of California after World War I. This was a semi-arid land of perennial sunshine, citrus groves and oil derricks pumping the fuel used by new automobiles on freshly paved highways. There was plentiful eastern Sierra water hauled south by an aqueduct, and electricity surging through miles of cables stretched across towering standards that went up in former orchards. Cottages and mansions arose from the brush of hillsides and mountains. The ambience of Mexico was pervasive. Exotic Asia seemed a stone’s throw farther east. The motion picture industry was spinning fabulous wealth from the dreams of average Americans.

Historian Walton E. Bean noted the population of the Los Angeles metropolitan area in 1920 was five times larger than it was in 1900. A year earlier, Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company built a major subsidiary in Los Angeles because the city could deliver the eight million gallons of water needed each day to run the factories. The U.S. Navy’s newly authorized Pacific Fleet docked at the bustling adjacent ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. A year later, Standard Oil opened an oil field in Huntington Beach, and Donald Douglas helped Los Angeles become a center for aircraft production.

Over the next decade, the population of Los Angeles County exploded from less than a million people to slightly more than two million. The number of registered private automobiles quintupled to about 806,000. Los Angeles had more factory workers than San Francisco and Portland combined. [31]

During the same period slightly more than a third of the city’s residents claimed membership in a mainstream religious denomination, according to Michael Engh, a Jesuit historian at Loyola Marymount University. Many of the rest of the spiritually inclined gravitated toward blends of Neo-Platonism and Egyptian magic, homespun interpretations of Darwin, Freud and Jung, and often watered-down and misguided notions about the esoteric traditions of Japan, China and India. Some teachers gained enormous followings by preaching certainty and success in the region they proclaimed to be the launch pad for the best that evolution had to offer.

“Los Angeles is the greenhouse of America,” Hall wrote around this time. “It is a place of experimentation in which we are combining facts and producing new species. . . . It is primarily fitted to be the greatest cultural center of the world. A city that is sacred in being a nucleus where the finer principles of life can come into expression.” [32]

Los Angeles was a sleepy agricultural center no more. Plans were being laid to build the world’s longest and largest water system from the Colorado River to the western coastal plain. Two-lane roads were being replaced with broad highways. Housing subdivisions were poised to expand in all directions. Downtown was buzzing with proposals for massive industrial development. Radio was opening new windows on the world. The 22-year-old Hall hoped to help infuse the emerging civic life with the highest ethical standards and a conscience. Whenever Hall found a book he liked, he’d recommend it. If he found a lifestyle that worked, he told about it. His growing reference library informed his personal interests: religious, philosophical and occult books and manuscripts—the older and more arcane the better. [33]

Out of Hall’s studies emerged a nagging sense that the sacred history of the world was being supplanted by a new religion of science and engineering. Everything before 1900 was considered fallacy, superstition and myth. Everything after 1900 was profound, glorious and true. [34]

“All that didn’t make sense to me,” Hall said. “It seemed as though in the effort to be modern we forgot that wisdom was neither ancient nor modern. The truth didn’t belong to any century. It belonged to all time.” [35]

Vowing to set the record straight—and return dignity to centuries-old beliefs—Hall began making plans for a comprehensive survey of “secret teachings concealed within rituals, allegories and mysteries of all ages.” His proposed “big book” would lend to metaphysics and myth the same nobility and heft otherwise reserved for classical works.

In the meantime, Hall chronicled his adventures in ideas in booklets and newsletters.

In May of 1923, Hall began publishing a periodical, The All-Seeing Eye, out of the home of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Young, followers who lived on West 20th Street, southwest of downtown Los Angeles. [36] Hall, who had been renting a small room in an alley off of Hill Street, moved in with the Youngs after the untimely death of their son. [37]

The unschooled but widely read publisher displayed an ability to write with surprising confidence and depth. “Those who have found joy in reading and bringing into play upon their lives the wisdom of past ages as it is immortalized in ancient tomes,” Hall said in one of the first issues, “have reached a great point in the growth of their being. But, above all, if we realize that the book gives to us that which we have given it, we then understand that mirrored in its pages are the thoughts and ideals of our own lives.” [38]

The Youngs’ spacious home became a hive of activity. It was there, with the assistance of a dozen volunteers from his Church of the People, that Hall produced his first literary efforts—a series of illustrated mystical booklets with titles such as Initiates of the Flame, The Maker of the Gods, The Face of Christ and The Last of the Shamans. [39]

At the end of each workday, Hall and his workers gathered in Mrs. Young’s expansive red dining room over casseroles of pink beans baked with onion, garlic and cheeses. Under shelves festooned with the Young family’s china, Hall entertained them with theories about “truths which the mind can never know.” [40]

Caroline Lloyd

Hall stood apart like some Don Quixote, a little mad and steeped in old magical works, inviting others to join him on what he called “the road to inner light.” His newspaper’s advertisements reached out to an emerging subculture in a city where the most popular dance was the “Feather Flutter” and a ham sandwich with trimmings and apple pie à la Mode went for 10 cents. [41] The Rosicrucian Fellowship in Oceanside advertised a new occult boarding school for children between four and seven. Dawson’s Bookshop in the 600 block of South Grand Avenue offered “the most complete stock of occult books in the West.” The Eutropheon restaurants on Olive Street and Hill Street promised “fresh raw foods.” The Reed Brothers Company funeral home in the 700 block of Washington Boulevard in Los Angeles announced “a unique method of caring for the body until the time of burial or cremation. . . By means of a refrigeration chest the body is perfectly preserved for the three days which are necessary, according to students of esotericism, for the complete and gradual disentanglement of the higher vehicles of man from his earthly body.”

The Psycho-Analytic Society in the 200 block of South Broadway promised “treatments for all psychopathic conditions and psycho-physiological aberrations.” A few blocks away, the International New Thought Alliance Convention challenged members and newcomers alike to learn to hook their minds up to the “power-house of the universe” to cure disease and achieve success.

Estelle Lloyd

Over at the Charles Radium Laboratories in the 1600 block of West Washington, customers were lining up to buy The Perfectacoil, a radium-powered mechanism advertised as “Nature’s assistant recreating every tissue, gland, cell and organ in the human body.” With the flip of a toggle switch, its developers said, a user could control three healing elements: “Magnetism provides the alkaline or creative polarity of electricity; Heat with its relief from pain and its power of bringing the blood to assist in elimination; Radium emanation from the pockets of radium ore (carnotite) that completely interline the coil.”

Some newspaper reporters found Hall’s androgynous appearance as interesting as his publications. Manly P. Hall, wrote reporter Alma Whitaker, in a 1923 article for the Los Angeles Times, “is tall, with unusually broad shoulders—football shoulders—but he wears his curly, dark brown hair bobbed like a girl’s, and even his face and eyes convey an almost feminine impression.” Whitaker also remarked that a majority of the people in Hall’s church pews were women.

Among them were dedicated acolytes such as Caroline A. Lloyd and her daughter Alma Estelle, wealthy scions with a reputation for attaching themselves to writers and bohemians who could be, as one of their relatives put it, “engaging for a fee.” Conversely, Caroline’s special interests—sculpture, classical music, stamp collecting and world travel—would have lasting impressions on Hall. [42]

Manly observes a holy man in India.

Caroline, a pretty woman with pale skin and wire-rim glasses, had studied drawing and miniature painting in Paris. Her daughter, a mannish, full-chested woman who favored walking shoes, vacationed in Europe with Ernest and Hadley Hemingway and kept an apartment in Paris a few doors down from the protean artist Man Ray. They belonged to the clan that controlled a fabulously productive oil field in Ventura County. Their family already was financing young mystery writer Raymond Chandler. [43] When the women began sending a sizable portion of their oil income to Hall, who was a frequent lecturer in the salon of Caroline’s home in Los Angeles’ Los Feliz district, relatives feared they had come under the spell of an evil guru.

“Caroline and Estelle were so taken by Manly Hall that some relatives thought there must be some sort of romantic involvement at work,” said attorney William Emerick, whose wife is a Lloyd family member. “There was none. He was only interested in their money.” [44]

The Lloyds’ financial donations started in the early 1920s and freed Hall to pursue a variety of interests and hobbies, most of them shared by Caroline. A stamp collector, he specialized in postage from countries that gave birth to the greatest saints and wise men. He traveled, exploring the world’s religious centers. A lover of classical music, Hall and Los Angeles Philharmonic pianist Douglas Colin Campbell experimented in the 1920s with some of the city’s first mood-enhancing light shows. “My father, who was known back then as the ‘young Paderewski,’ would perform while Manly lectured,” recalled Campbell’s daughter, Cai Taggart. “All the while, a color wheel would turn and cast various shades across the stage. It was all choreographed.”

Donations from Caroline Lloyd and his own congregation paid for Hall’s first trip around the world to study the lives, customs and religions of countries in Asia and Europe. Hall sailed out of San Francisco on the luxury liner S.S. Franconia on December 5, 1923. He reached Yokohama in late December of that year, after a massive earthquake had devastated the Japanese city and left corpses floating in its harbor. [45] Years later, he recalled, “we found a city of a half a million people without a single building standing. We found pain, sorrow, and misfortune on every hand.

“But for the first time I became aware of the quality of the Japanese character which lingered with me for a long time. My rickshaw man was to take me to the main hotel in Yokohama, which incidentally now was. . . a shack put together out of empty beer bottles with a cot in it. . . And he asked if he could stop for a moment. . . He wanted to pause for just a few moments to say a prayer in the block where his family had died. His mother, his father, his wife and his children had all died together. [46]

“After that experience with him, I asked him, ‘How do you feel about all this? What does this mean?’ He said, ‘I have faith. I believe. . . I must accept. I cannot question. I believe that those whom I have loved have left here but they are still alive. I believe they will be born again. I believe they will live here. I believe there is no end. And in this hope of the continuance of their life I have peace.’” [47]

Photographs show Hall clad in white trousers, a heavy dark coat and pith helmet as he crossed to Korea, stayed briefly in Peking, China, and went on to Burma and India, arriving just as Gandhi was released from prison after a hunger strike. After delivering a lecture in Calcutta, he was invited to walk in a parade and his appearance was publicized in local newspapers. He traveled on through Egypt and central Italy.

Throughout that 38,000-mile journey he called the “single most important episode in my life,” people were either fascinated or frightened by the imposing self-styled mystic from Los Angeles armed with endless stories of reincarnation, odd gods and lost continents. His remarks often provoked news articles with headlines such as “Bizarre Preacher Startles Ad Club,” “Noted Radical Preacher from Los Angeles Speaks,” and “A World Religion is Advocated by Tourist.”

In Honolulu’s Wela-ka-hao newspaper, a reporter wrote: “Rev. Mr. Hall is in physical appearance a striking figure. Dressed bizarrely, he wears black hair in the fashion of a stage poet, cultivates a languishing glance and evidently yearns to be classed as a mystic. But he is modest. He disclaimed being the reincarnation of Pythagoras, as a reporter for the morning paper had quoted him as saying he was, although he admitted being a believer in reincarnation, which he said he had been preaching in his church in Los Angeles for two years.” [48]

Hall makes headlines in 1923.

Hall dispatched dozens of letters to followers back home. One described his disgust with a white man he witnessed kicking and beating a Hong Kong resident for having “the audacity to walk on the same sidewalk with him.” [49] Another spoke of the hilly roads of Jerusalem, where, Hall opined, life had not changed all that much since biblical times. Yet another told of the superhuman powers of a holy man in Benares who seemingly induced a mango sapling to grow on the spot with flute music.

Hall also wrote, “I once discussed the problem of miracles with a very learned Brahmin pundit whose conclusions on the subject may be summarized as follows: ‘You Christians believe that He [Jesus] turned water into wine; that He raised the dead, healed the sick, passed through closed doors, and multiplied the loaves and fishes. Do you believe the day of miracles ended two thousand years ago? Your Jesus told His disciples that greater things than He did they should do. Why, then, do you declare the miracle-working of India to be false?’” [50]

He returned to the United States in February 1924 by way of New York, with more than four hundred photographs taken with a four-by-five Graflex box camera, which would accompany him for decades. [51]

When he next took to the pulpit at his Church of the People, he was sporting a beard. His adherents expressed their displeasure with his whiskers by dropping a few razors into the collection plate.

As Easter rolled around in 1924, the now worldly Hall was lining his church’s course with an array of novel activities including stereopticon slide presentations of his trip, and feisty public debates over provocative topics: Should the United States police the world? Is modern democracy detrimental to culture? Are motion pictures destructive of public morals? In one debate, Hall opposed the idea that “women have no faith in god or man.”

In November 1926, Hall revived the All-Seeing Eye as a 10-cent weekly newspaper devoted to philosophy, science and religion. Published out of Room 301 in the Trinity Auditorium Building near 9th Street on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles, it now also served as a clever platform in which to trumpet progress being made on Hall’s elaborate compendium of occult philosophy and symbols.

Hall’s weekly messenger drew heavily from his growing home library, and laid out the basic themes and principles and literary forms that he would rely on throughout his long, curious career. He included news items clipped from mainstream publications, question-and-answer sections, notices of upcoming events and feature articles on interpretations of biblical stories, Egyptian initiation rites, chakras and glands, alchemy, astrology, Buddhism and reincarnation. He also wrote about the mysterious magician Count de St. Germain, Madame Blavatsky and the theory that Sir Francis Bacon was the true author of Shakespeare’s plays.

Other articles spoke of the healing powers of arts and crafts, the grinding mindlessness of modern city life, the relationship between stress and disease, and the false promises of most of the metaphysical pursuits that were suddenly all the rage in Los Angeles.

“Nearly all who spend a few years in modern metaphysics,” he warned in the March 23, 1927 edition of the All-Seeing Eye, “come out broken in mind and body, self-centered egotists who do not know where they are mentally, have lost all desire to work, and wander from one teacher to another searching for knowledge until at last the insane asylum or the state grave yard claims them.” City life, he observed a month later, “is just a rush from one street car to another, from one lunch stool to another, from one excitement to another. There is one general result of it all and that is a nervous breakdown.” For relief, Hall prescribed, among other things, the writings of Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, the 16th-century Swiss medical physician and alchemist also known as Paracelsus.

The explorations of the brilliant, belligerent and pudgy Paracelsus, one of the first to stress the power of mind over bodily function, helped trigger a struggle between medicine and magic. Paracelsus proposed that conflicted spiritual convictions can lead to disease, and that the vital energy of life is channeled into the lives of living things. Energy out of control, or blocked, disrupts the mental and emotional life and renders the individual vulnerable to sickness. A great magician is a master of this energy, which he called forth with the magic wand of his will.

Paracelsus did not invent these ideas. They were adapted from myriad early mystics and religious doctrines. Socrates, for example, once chose a secluded, shady place to meet with his disciples because the spirits who inhabited that spot would contribute dignity and richness to the discourse. Iamblichus believed in guardian spirits not unlike Guardian Angels of Christianity. Pythagoreans described Deity as an infinite being whose body is composed of the substance of light and whose soul is composed of the substance of truth. Kabbalists regarded the psyche as an organism, and physical creation as a manifestation of spiritual emanations. Ancient Oriental acupuncture procedures in which small needles are inserted into certain body points to improve health grew out of the belief that disturbances in the flow of natural life forces lead to a disease state.

“Paracelsus,” Hall wrote, “the hermeticist and the mystic, the original thinker who gained his knowledge not from long-coated pedagogues but from dervishes in Constantinople, witches, gypsies and sorcerers; who invoked spirits, captured the rays of the celestial bodies in dew, of whom it is said he cured the incurable, gave sight to the blind, cleansed the leper, and even raised the dead, and whose memory could turn aside a plague—this ‘magician’ is the father of chemical medicine.” [52]

Long before psychologists began talking about complexes, obsessions, various neuroses and stress-related diseases, Paracelsus had identified them as harmful parasitic organisms that feed off the abnormal thoughts and emotions of the person who has the problems. Paracelsus’ medical therapies included the cultivation of wisdom and positive thoughts.

“As a man may have a moldy piece of bread,” Hall wrote, “so he may have a mind on which certain lichens have fastened, growing and flourishing off of his vitality. . . This is not a rational creature, but something that lives for self-preservation, like all living things. Most of us have one, highly developed, and most people have several.” [53] Lichens or not, Manly P. Hall was about to become one of the most celebrated spiritual figures of the 1920s.

THE HAND OF THE MYSTERIES

The original drawings from which this plate was taken is designated the hand of the philosopher which is extended to those who enter into the mysteries. When the disciple of the Great Art first beholds this hand, it is closed, and he must discover a method of opening it before the mysteries contained therein may be revealed. In alchemy the hand signifies the formula for the preparation of the tincture physicorum. The fish is mercury and the flame-bounded sea in which it swims is sulfur, while each of the fingers bears the emblem of a Divine Agent through the combined operations of which the great work is accomplished. The unknown artist says of the diagram: “The wise take their oath by this hand that they will not teach the Art without parables.” To the Qabbalist the figure signifies the operation of the One Power [the crowded thumb] in the four worlds (the fingers with their emblems). Besides its alchemical and Qabbalistic meanings, the figure symbolizes the hand of a Master Mason with which he “raises” the martyred Builder of the Divine House. Philosophically, the key represents the Mysteries themselves, without whose aid man cannot unlock the numerous chambers of his own being. The lantern is human knowledge, for it is a spark of the Universal Fire captured in a man-made vessel; it is the light of those who dwell in the inferior universe and with the aid of which they seek to follow in the footsteps of Truth. The sun, which may be termed the “light of the worked,” represents the luminescence of creation through which man may learn the mystery of all creatures which express through form and number. The star is the Universal Light which reveals cosmic and ceslestial verities. The crown is Absolute Light—unknown and unrevealed—whose power shines through all the lesser lights that are but sparks of this Eternal Effulgence. Thus is set forth the right hand, or active principle, of Deity, whose works are all contained within the hollow of His hand.

Copyright © Philosophical Research Society | Manly P. Hall | Artist: J. Augustus Knapp