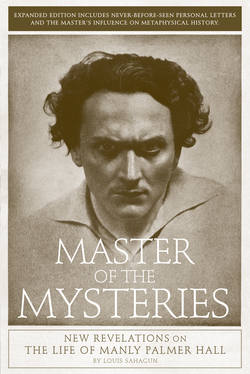

Читать книгу Master of the Mysteries - Louis Sahagun - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

The Big Book

WHEN HALL STOOD BEFORE CROWDS IN DOWNTOWN AUDITORIUMS AND THEATERS AND TALKED ABOUT THE URGENCY OF SEARCHING FOR THE WISDOM HIDDEN IN THE MYTHS AND SYMBOLS OF ANTIQUITY, IT WAS HARD NOT TO BELIEVE HE WAS SPEAKING FROM THE HEART.

Part showman, part shaman, Hall wore a dark tailored suit and sat mid-stage, his hands resting palms down on the arms of a baronial chair that was bathed in light. He spoke for one and a half hours—not a minute longer. Whether his subject was Egyptian initiation ceremonies or mythic water sprites, he concluded abruptly with the same sign-off: “Well, that’s about all for today, folks.”

Hall also drew audiences on visits to the Bay Area, where he took out large advertisements in the San Francisco Examiner trumpeting upcoming talks by the “author, lecturer and world traveler” on such subjects as “the occult anatomy of man” and “the tree of the universe.”

At 24, Hall was living up to the fundamental Masonic codes he summarized in a note he penned in ink (in apparent violation of Max Heindel’s warning) that remains one of the few generous samples of his handwriting beyond his characteristic sign-off: Sincerely Yours, Manly P. Hall. “To learn is to live, to study is to grow, and growth is the measurement of life,” he wrote. “The mind must be taught to think, the heart to feel, and the hands to labor. When these have been educated to their highest points, then is the time to offer them to the service of their fellow man, not before.”

Between public appearances Hall was working at a furious pace, researching his massive survey of myths, magic and symbols, which he promised would be “the most elaborate and most beautiful volume ever printed on the West Coast.”[1] He dictated portions of the book four hours each day to a stenographer at the southwest Los Angeles home of Mr. and Mrs. Young. After the manuscript was about two-thirds done, he started looking for a publisher.[2]

Hall took his rough draft to H.S. Crocker Co. in San Francisco, which made him an offer. If Hall could secure the interest of book designer John Henry Nash, who once worked as a printer to the Vatican, the Crocker Co. would publish the effort. Nash was persuaded to sign onto the project. Hall wrote the closing chapters of the book while the first were on the press.[3]

The result was a gorgeous, dreamlike book of mysterious symbols, concise essays and colorful renderings of mythical beasts rising out of the sea, and angelic beings with lions’ heads presiding over somber initiation rites in torch-lit temples of ancestral civilizations that had mastered latent powers beyond the reach of modern man. While others in his domain tended to build walls around their narrow fields of expertise, Hall’s book tried to embrace the whole of esotericism.

Seven years in the making at the staggering production cost of $150,000—much of it raised through advance sales—Hall completed his Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy, also known as The Secret Teachings of All Ages and The Big Book, before his 28th birthday.

Magnificently illustrated with 54 original full-color plates of ancient and medieval emblems and figures by noted illustrator J. Augustus Knapp and two hundred black-and-white illustrations borrowed from rare occult works, the 14 ½-pound book resembled the old volumes on esoteric arts and sciences that he’d been collecting for more than a decade.

Within its massive 13-inch by 19-inch covers Hall had assembled an impressive collection of esoteric lore drawing from more than six hundred sources. It remains a veritable “open sesame” into the world of occult traditions. The human body in symbolism; the Pythagorean theory of music; ceremonial magic; talismanic jewels; the significance of the Egyptian scarab; the practice of alchemy, and Hebrew mysticism were just some of the subjects explored in Hall’s tightly written essays.

Hall dedicated Secret Teachings to “the proposition that concealed within the emblematic figures, allegories and rituals of the ancients is a secret doctrine concerning the inner mysteries of life, which doctrine has been preserved in toto among a small band of initiated minds.”[4]

Legendary publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst wrote Hall to tell him that he had discovered the only typographical error in the book: in the index, Madame Helena Blavatsky’s first name was misspelled Helen.

The first two editions of the book totaling 1,100 copies sold out in advance at a cost of about $100 per copy. Subsequent editions sold for $75 on terms of $15 down and $15 a month. Its instant success catapulted Hall into the national spotlight. “Into this volume has been compressed the quintessence of a colossal learning,” said George Barron, curator of San Francisco’s de Young Museum of fine arts. “It is a living human document pulsating with mental and spiritual vibrations of a profound thinker. It takes all knowledge for its province, and reduces whole libraries to the compass of a single tome.”

A special edition bound in full vellum and stamped in gold was presented to the Crown Prince of Sweden at a ceremony held in the Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C., on October 15, 1928. Among the celebrities who signed the event registry were U.S. General of the Armies John Pershing; the charge d’affair of France; the secretaries of the German and Japanese embassies, and the grand master of masons in the District of Columbia. [5]

Hall personally presented a copy of the first edition to his old friend, Sidney J. Brownson, who was by then a fragile and ailing man in his eighties. “Toward the end of his life, the book must have seemed large and heavy,” Hall recalled in an essay decades later. “But he toted it about with great joy.”[6] Brownson was 88 when he died in his garden in his sleep with a copy of the Hindu holy book Bhagavad-Gita on his chest and a small New Testament in his hip pocket.

Eighty years later, with more than a million copies sold, The Secret Teachings of All Ages remains one of the most popular introductions to esoteric traditions.[7]

Hall’s life would never be the same. Overnight, he went from being just another earnest young preacher in the City of Angels to becoming an icon of the increasingly influential metaphysical movement sweeping the country in the 1920s. His book challenged assumptions about society’s spiritual roots and made people look at them in new ways. His presence at a dinner gathering or civic event inspired awe.

But he didn’t bask in the attention for long. A year later, he published his Lectures in Ancient Philosophy: An Introduction to the Study and Application of Rational Procedures, which features a frontispiece portrait of Hall wearing a cape and striking a Byronic pose that was photographed by noted Hollywood cameraman William Mortensen. In 471 pages drawn from lectures delivered in San Francisco and Los Angeles, it amounted to a literary complement to his Secret Teachings of All Ages. There are the familiar voices from the pagan metaphysical pantheon, but also those of psychologist Sigmund Freud, botanist Luther Burbank, educator Samuel Johnson and the so-called “Plato of Masonry,” Albert Pike.

The book opens with a discourse on space, form and potential that sounds surprisingly similar to Big Bang creation scenarios offered by modern cosmologists. It’s all reflected in the simplest of symbols: dot, line and circle. Think of a blank piece of paper, he says, as that space which contains all existence in a potential state. The universe issued forth out of that indefinable fullness as a state of universal intelligence, or unity, comparable to a dot, much as an oak tree emerges from an acorn. The conscious activity of that emergence is reflected in the line. “The center and the circumference are thus blended in the connecting line—conscious activity or intelligence,” he writes. [8]

Continuing that analogy, a human being’s greatest potential is realized by applying intelligence, emotion and purpose in a manner least prone to error or illusion: philosophy. It follows that the highest form of consciousness, enlightenment, is born of a highly disciplined mind.

The same principles applied to the average modern family, where young persons were being raised with all the comforts, but little discipline, Hall said. The hope of achieving strength in character and success later in life, he argued, was remote “without having first experienced any snappy toeing of the mark at home.” [9]

In a passage titled “Symbolism, the Universal Language” he writes: “Confront the untrained mind with some symbol or fable, and it will construct a confused and meaningless explanation, usually far more complex than the figure warrants, and as senseless as a macaw’s chatter.” [10]

“Symbols consequently change the meanings according to the level of intelligence upon which their interpreter functions. . . The purpose of symbols is to uncover the limitations of mortal consciousness by continually emphasizing the insufficiency of the interpretations placed upon them.” [11]

Hall freely sorts through a tossed salad of spiritual imagery from disparate times and places and discovers common ground, and patterns: the universe is alive and consists of a network of mathematical connections between different levels of reality. “In the Ancient Wisdom it was also declared that the sacred mountains of the world rose in seven steps or stages (as the Meru of the Hindus),” Hall writes, “and it was from the high place, or the seventh step, that offerings were made to the Lord whose name is Blessed. Not only did the holy place rise in seven platforms or levels, but upon its topmost level was usually erected a triform symbol of the Divine Nature itself. Thus, the seven steps, complemented by this three-fold figure, became the mysterious Pythagorean decad, or the symbol of the tenfold order of the universe. Jacob’s ladder then actually becomes the symbolic mountain or pyramid.”[12]

Conventionally-minded skeptics dismissed that kind of talk as nonsense. Believers figured Hall was onto something profound and exciting. But the festive prosperity of the 1920s was about to implode into a decade of depression that would bring unemployment and personal hardship to millions. When the stock market crashed in the fall of 1929, Hall watched as many who got rich by exploiting pioneer dreams quietly disappeared or retired to enjoy their gains, while their adherents were left sadder, wiser and poorer.

Hall, with books like his Secret Teachings of All Ages, was more in demand than ever. Hailed as one of the world’s most promising young thinkers, Hall was called Maestro by his congregation. In a magazine article, Hindu author Basanta Koomer Roy referred to Hall as “the greatest sage in America” and compared his mind to Albert Einstein’s. A feature article published in the Los Angeles Examiner in 1930 described him as “an original. Distinct. In a class by himself.”

“I do not recall anyone who resembles him in appearance, in personality, or in mental viewpoints,” the article said. “He is positive. He is poised. He is an orator. He spurns manuscripts or notes. He has a clear, vibrant voice. Fluent of speech, his style is epigrammatic, and is marked by the frequent employment of striking antithesis.”

Hall was still in his twenties and he was chumming with the rich and famous. That made him a sort of icon for Hollywood hangers-on who imagined their chances of grabbing a piece of the action would be vastly improved by knowing him. Hall was also an unlikely sex symbol, given that a few years earlier he had preached against intimacy, even in marriage, as an obstacle to reaching the highest levels of human consciousness.

That didn’t stop Caroline Lloyd’s lesbian daughter Estelle from proposing marriage to the philosopher, who let her down gently. “Her infatuation with Manly was not so much physical as intellectual,” recalled physicist Donald Lloyd, Estelle’s nephew.

Then 28, the high-profile, eligible bachelor expressed a change of heart on the issue of celibacy in a little book of essays published in 1929 under the title The Child’s Place in the Plan.

“Among the early pagans, celibacy was not regarded as a priestly virtue, yet their standards of ethics far surpassed that of our own day; nor were their aesthetics in any way compromised,” he wrote. “Nearly all the renowned philosophers and World Saviors were married men.” [13]

He pointed out that the Egyptian Hermes; the fire prince of Persia Zoroaster; the Greek philosophers Pythagoras, Socrates and Aristotle; Gautama Buddha and Mohammed were all fathers. “The individuals who fear that a family may retard their progress toward perfection may be well satisfied if they reach a degree of excellence comparable with those here listed,” he wrote, “and at the same time give other unfolding lives an opportunity to bask in the sunlight of their superior wisdom.”

On April 28, 1930, Hall married his secretary of five years, Fay B. de Ravenne, a strikingly attractive petite 28-year-old brunette astrologer from Texas with fine features and big plaintive eyes, perhaps expressing the sadness of the pain of her inner life. It was Hall’s first marriage, and Fay’s second. The ceremony was conducted without fanfare at the Rosicrucian Fellowship in Oceanside and officiated by Hall’s friend, mentor, and frequent guest lecturer Augusta Heindel. She announced the marriage in the June 1930 edition of the fellowship’s Rays magazine under the banner: “Wedding bells are ringing, mocking birds are singing.” “The writer was not a little surprised to have Mr. Hall and his lady, Fay B. de Ravenne, call on her on Monday, April 28, when she had the honor of performing the marriage ceremony,” Heindel wrote. “The bride has been associated with Mr. Hall as his secretary for about five years. We know that all their friends join us in wishing this bride and groom much joy and a long and successful life.”[14]

Not much is known about the dark beauty. Fay rarely appeared with her husband in public, and all references to their life together were mysteriously excised from Hall’s voluminous archives after her death. Then, too, Hall’s closest friends were fiercely protective of his public image and never gossiped about his private life. All that can be said about Fay exists in available census data, a wedding certificate, a few photographs, a coroner’s report and a handful of sketchy anecdotes.

Hall’s young wife was plagued by various illnesses, and grew jealous and angry as his popularity soared and the lecture circuit took him away from home on lengthy trips. It didn’t help that Hall had failed to credit Fay for her help in completing his Secret Teachings of All Ages, or that his personal valet had a serious crush on her.

Close friends recalled Fay acting sullen and resentful at Hall’s lectures while sitting beside a small table and taking money for his books. “I only saw Fay a few times,” recalled Pat Levitt in an interview. “But I knew there were troubles there.”

Manly and Fay Hall. Photo by William Mortensen

Initially, the Halls lived with Mr. and Mrs. Walter Young on West 20th Street, then hopscotched from one modest apartment to another on the north side of downtown. Among their closest friends were William Mortensen, one of Hollywood’s most famous photographers, and his ravishing wife and principal model, Myrdith. Based in a cottage tucked in Laguna Canyon, Mortensen was a darkroom artist best known for his highly stylized portraits of celebrities including actresses Fay Wray and Marlene Dietrich and musician Jascha Heifetz. He was set photographer for director Cecil B. DeMille’s 1926 movie King of Kings. [15]

During their years together, the Halls and the Mortensens shared mutual interests in the occult, magic, and parlor magic, according to Anson and Peggy Beman, who were students of Mortensen in 1951. Hall, for example, liked to stand in Mortensen’s yard and appear to pluck silver dollars out of the air, then toss them in a bucket. “Some of the best times were after dinner when Bill would sit in his favorite chair, smoking his ever-present pipe and we would have discussions about psychic phenomena, magic, old Hollywood,” Peggy Beman recalled decades later in a memoir entitled Memories of Our Friends in Laguna Beach. [16]

“Bill and Myrdith were great friends with Manly Hall, a well-known magician in the 1930s,” she wrote. “They, along with other friends, experimented with Oujia boards, séances and table tipping at their little adobe house in a big orchard in the canyon. The house was built over an old Indian burial ground and they swore they contacted one of the Indians, and that Myrdith actually saw him. I don’t know if they were drunk or sober at the time. I do know that they both firmly believed in such things.”

Beman added that Mortensen “always said, ‘Don’t get involved with psychic phenomena of any kind, it’s too dangerous.’”

Hall was working harder than ever, and he shifted his philosophic activities to include private counseling and public service. In late 1930, a six-month lecture campaign carried him to the nation’s largest cities including Chicago and New York, where he attracted capacity audiences at Town Hall, the Pythian Temple and Carnegie Hall. He also spoke regularly on New York radio station WOR, and began preparing for a trip to Mexico and Central America.

In the spring of 1931, he left New York by boat for the entry port of Progresso on the peninsula of Yucatán to conduct research at Mayan ruins on the myth of the snake-bird god Quetzalcoatl. Then he proceeded by train to Mexico City, where he made short trips to the region’s Toltec and Aztec archeological sites, where he hoped to confirm flamboyant American political reformer Ignatius Donnelly’s claims of a submerged paradise that existed eons ago.

Later that year, Hall’s name cropped up in a story published in the New York World-Telegram under the headline “Head of Supreme Government of the World Inc. Wants His $1,400 Back.” A man identified as “Brother Thomas” had invested in an occult bookstore owned by a transplanted California mystic. Thomas wanted out of the arrangement immediately after reading an article in Hall’s magazine All-Seeing Eye, which he hoped to use as evidence in a jury trial. It warned, in part, “Not a few sincere but sentimental people have impoverished themselves, hazarded the future of their families and wasted the best years of their lives in ill-advised attempts to attain that abstract state commonly denominated ‘spirituality.’” [17]

The same could be said about astrology. But Hall reserved a special fondness for the storied association between the planets and human characteristics. Hall was an admirer of Evangeline Adams, astrologer to the rich, famous and powerful, who by 1914 had gained enough leverage to challenge and have modified New York’s statute against fortune telling as it applied to astrologers. Her clientele ranged from working folks to powerbroker financier John Pierpont Morgan, who reportedly boasted, “Millionaires don’t use astrology, billionaires do.” Tenor Enrico Caruso reportedly never crossed the Atlantic during World War I without first consulting Adams to get the safest times and dates for traveling.

In late October 1932, Adams was about to undertake a risky business venture in the depths of the Great Depression: writing a book listing the good and bad astrological aspects to watch for during each month of the following year. Her prospective publisher felt that sales would have to be strong right away, given that the book would be of no use in 1934. Adams offered to pay Hall $100 if he would write an introduction to the book, an endorsement, she explained, that “would help the sale of the book here in the East, as well as in California.” [18]

Adams died in New York about a month later. Her book, The Evangeline Adams Guide for 1933, was published posthumously. The introduction by Hall begins:

“The right of a branch of learning to exist is determined from its use-value, and the distinguished position always occupied by astrology in the history of nations is due largely to its practical value in unraveling the tangled skein of circumstance.”

The book sold well, earning warm reviews in venues including the Saturday Review of Literature. In any case, Hall generally ignored the Guide for 1933’s New Year’s admonition for those who, like himself, were born on March 18: “This is not likely to be a favorable time for making purchases, for there will be a tendency toward extravagance,” and, “Avoid catering to your love of the good things of life, and especially avoid over-eating and drinking.” [19] Instead, he binged on sweets and avoided exercise, personal failings exacerbated by long hours of sedentary research and thyroid problems that were making him obese. To cover up his physical problems, Hall ordered up tailored coats that draped over his expanding waistline like navy-blue parachutes. Some of his congregants contrived a story to explain his sagging stomach: He’d contracted elephantiasis, a disease characterized by thickening of the skin and underlying tissue, during a trip to India.

With the financial assistance of the Lloyds, the early 1930s were Hall’s most intensive years of book and artifact collecting, a quest he called rich in adventures that brought him in contact with many unusual individuals and institutions. Hall traveled to France and England, where he acquired his most extensive collection of rare books and manuscripts on alchemy and esoteric fields from London auctioneers, Sotheby & Company. [20] Because of the serious economic depression afflicting the world at the time, bidding was relatively conservative, and Hall, through an agent, was able to acquire dozens of books and manuscripts at reasonable prices. They included an original triangle-shaped manuscript by 18th-century magician Compte de St. Germain purporting to hide clues to the locations of all treasures lost at sea; instructions for finding diamond, gold and silver mines; and formulas for living longer than a century with the freshness of a man of 50. [21]

In 1934, Hall attended a special meeting of the World Fellowship of Faiths in London, where he met explorer and political administrator Sir Francis Younghusband, who was instrumental in opening Tibet to British trade after the turn of the 20th century. Through contacts provided by Younghusband, Hall secured the Ripley Scroll, a 20-foot-long, hand-painted manuscript considered one of the outstanding artistic alchemical works. In Atlantis, an obscure bookshop on a street leading to the main entrance of the British Museum, he bought several choice items including a manuscript on vellum explaining intricate diagrams drawn from the Kabbalah, a Jewish mystical tradition passed lip to ear. At an auction of the holdings of the late movie idol Rudolph Valentino, Hall secured a bishop’s silver ring of the 12th century, which Valentino had worn in the film The Son of the Sheik.

Letter from Luther Burbank, 1926

Browsing Mexican bookshops around this time he was able to make an especially valuable addition to his research collection: a post-Columbian work on the early societies of Mexico and Central America known as the Florentine Codex of Friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Hall made photographic copies of the Codex for use by university libraries. [22]

His circle of friends expanded along with his collection and included some of the nation’s most famous thinkers and mystics. One was famed botanist Luther Burbank, a short, gentle man with a shock of white hair who taught him that “if we meet the challenge of the future with the simple wisdom bestowed by nature and exemplified through cooperation and brotherly love, we can build a strong new people in America, and the children of the future will have a better chance to fulfill the destiny which nature and nature’s God have decreed.” [23]

In his lectures, Hall attributed much of the Santa Rosa plant breeder’s strides developing new, economically important varieties of fruits and flowers to the fact that he often got down on all fours and prodded them with kind words. “He was not sure that the shrubs and flowers understood his words,” Hall recalled in an essay, “but he was convinced that by some telepathy, they could comprehend his meaning.” [24]

At an Authors Club meeting at the Hollywood Athletic Club, English scholar, scientist, and gentleman naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton talked about his books, which brought the wonders of nature to city-dwelling children. No sooner had the big rangy man with long gray hair and bright, humorous eyes completed his talk than Manly Hall strode up, extended his hand and said, “Mr. Seton, I want to know you.” [25] Seton, who was nicknamed “Chief” because of his affinity for American Indians and their culture, had an iron grip. They took to each other easily. Over the years, Hall was a frequent guest at Seton’s huge estate in New Mexico, which was topped with a rambling house dubbed “The Castle.” From there, Hall and Seton rode out on horseback to watch Hopi ceremonies and rain dances, and witness the flagellant rites of Penitentes reenacting Jesus’ journey to Calvary. [26]

On the East Coast, Hall’s followers were as fascinated by his growing reputation as an enlightened initiate as by his authoritative writings on astrology, Freemasons, the mysteries of life and his exciting predictions. He prophesied that by 1950 “robbery and thievery” would be done away with because people would be more honest and have everything they needed.

Hall was especially popular lecturer among the “town-car” audiences at the 29-story Roerich Building museum on New York’s Riverside Drive, which had been built by Russian artist and mystic Nicholas Roerich to showcase his paintings and be a creative center for outstanding writers, spiritual leaders and artists. The first few floors housed Roerich’s paintings. But an upper-floor penthouse suite with spectacular views of the Hudson River and city in all directions was used for private gatherings and occult explorations. Hall, who had been invited to deliver a series of lectures and classes at the museum, was a regular participant in the elaborate tableaus hosted by choreographer and dancer Natacha Rambova, the former wife of screen idol Rudolph Valentino, Theosophical writer Talbott Mundy, newsman turned philosopher Paul Brunton, and Svetoslav and George Roerich, the handsome sons of Nicholas and Helena Roerich. [27]

Hall initially planned to spend a month or so at the Roerich museum and elsewhere in New York, but extended his trip to include a series of lectures at the Pythian Temple. During his six-month tour, Hall presented more than a hundred lectures and radio talks. He also made time during his busy schedule to study sculpture at the museum, later fashioning remarkable likenesses of Theosophist Blavatsky, the Masonic philosopher Pike, and Mahatma Gandhi.

In her two-volume Collected Letters, 1929–1939, Helena Roerich expressed a particular fascination with a portion of Hall’s book The Occult Anatomy of Man, opining on the composition of blood long before the electron microscope became a standard medical tool: “The blood of every man is individual. When crystallizing, it forms into geometric patterns which differ with every person... The story of one’s soul is written in his blood. The position he occupies in evolution, his hopes and fears, are all imprinted on the etheric forms which flow through his bloodstream. . . so that by means of blood analysis a far surer system could be evolved for crime detection.” [28]

Those kinds of ideas were spreading like wildfire among some of the most acclaimed creative minds of the era. Even such internationally famous artists as Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky and Constantin Brancusi, and inventor Thomas Edison, for example, touted Theosophical notions. Edison would spend his last days trying to build a receiver capable of picking up signals from the dead.

It galled Hall that such notions had no place in American universities, which to him stood as bastions of science and technology. He decided to counter ivory-tower materialism with a spiritual center in Los Angeles of his own design and purpose, one he envisioned as “the center of a new way of life in the midst of the great Pacific theater of the future.” [29] Its mission would be to teach the “practical idealism” preserved in over 100,000 of the wonder-texts of antiquity, develop programs for the good of society, and then excite his students’ desire to put them to work in everyday life. It would be, he believed, a guiding light for a city that was growing out of its skin. Hall would be its occult theologian.

On November 20, 1934, Hall’s nonprofit Philosophical Research Society bought a prime piece of real estate overlooking Los Feliz Boulevard and the hills leading to Griffith Park from Capitol Holding Company for a mere $10, according to county records. The three-quarter-acre lot was originally owned by Anna D. Bockius, who paid $700 for it in 1918. [30]

By the time she died in 1933 it was valued at $6,720, and controlled by her son, Charles R. Bockius, a vicious ex-con with a drinking problem and a formidable criminal record. He was on parole at the time after being released from San Quentin in connection with a drunk-driving incident that left one man dead and another seriously injured. In a separate, earlier case, Bockius beat and then shot a man in the leg after learning the victim had been having an affair with his wife. [31]

At the time of the sale, Bockius, who billed himself as a realtor, was involved in nasty divorce proceedings. It was not clear how Hall managed to get the land for a pittance, although county officials speculated it may have been acquired in a partnership arrangement, or essentially given to him in the depths of the Depression.

On an overcast early morning on October 17, 1935, about one hundred people assembled in a field of wild mustard on the property and broke ground for his Philosophical Research Society. The first cornerstone was laid at a specific moment just after midnight to coordinate with stars aligned for maximum longevity. According to Hall, the crowd looked up to see those stars shining brightly through a brief break in the clouds. [32]

Rendering of Hall’s proposed PRS center

The proposed lecture hall

“This society,” Hall said at the opening ceremony, “is dedicated to the ensoulment of all arts and sciences and crafts. In harmony with the classical point of view we feel that there is a pressing need for a nonaligned institution without creed or dogma, where persons of all beliefs can seek a better understanding of life’s plan. The society requires no membership, and no one is expected to accept any arbitrary dogma. We are all here to grow—to become better and more useful.” [33]

The architect was Robert B. Stacy-Judd, a British architect, amateur archeologist and explorer who instilled a distinctly Mayan and Egyptian flavor into many Southern California buildings over the years. Stacy-Judd even wore feathered Mayan costumes to cocktail parties. [34]

“The architecture of the new building will be Mayan, simplified looking, perhaps, something like one of the buildings on that fabled continent of the Atlantic that sunk into the sea before the beginning of what we call history,” Hall told Los Angeles Times reporter George Addison in 1935.

It began with a single unit of reinforced concrete that included a front office, print shop, bindery, and library. Before long, its dark wood shelves were lined with the donated book collections of scholars of comparative religion and his own rare books and art objects Hall had collected in his travels around the world: a copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead from 500 B.C., Babylonian and Chaldean writings on clay tablets, Chinese oracles inscribed on human bones, the original works of great philosophers, authors and poets, and sacred writings of almost every religious doctrine, past and present. Hall’s print shop was a hub of activity, a cluttered room with large windows where he spent long workdays directing layouts, linotype operations and binding for his newest books. A few doors down was Hall’s office, a cramped quarters featuring a large brown desk and cabinets containing books and such cherished curiosities as a life-size statue of an Egyptian cat—a symbol of the clairvoyant’s ability to “see in the dark”—which he habitually stroked a few times before leaving to deliver a lecture. [35]

The proposed courtyard

On some days, Hall and his friends would ride horses in the hills of sprawling Griffith Park. Occasionally, they would converge in a circle with horses facing each other while Hall delivered impromptu lectures jokingly referred to as “sermons on the mount.” [36]

Avoiding evil thoughts Rosicrucian-style

They still talk about how Hall and a troop of followers showed up one day in 1935 in Long Beach’s popular Acres of Books store. Hall, draped in a flowing black cape, only needed to glance at a book and one of them would take it off the shelf, and then open it for his perusal. [37]

The Philosophical Research Society was only one of dozens of new mystical retreats established throughout California. One of Hall’s chief rivals, Harvey Spencer Lewis, had established the International Headquarters of the Ancient and Mystical Order Rosae Crucis in colorful replicas of Egyptian temples erected in a park-like setting in downtown San Jose, a few hundred miles to the north. The enclave included research laboratories and a clinic where latter-day alchemists tried to cure people of ailments ranging from depression to cancer with mind-over-matter techniques.

H. Spencer Lewis

The similarities between Hall and Lewis were striking. Both were relentless students who had been born to Welsh fathers and inherited artistic and literary tendencies. They were both plump and favored dark suits with crisp white shirts and blue ties and shared the curious habit of avoiding boring conversation or harangues by dropping their chins on their chests and falling asleep only to awaken—as if on cue—15 minutes later.

Each had enormous Rosicrucian crosses dangling from chains around their necks.

Hall and Lewis, who started out as an advertising consultant to railroad companies, were both exceedingly persuasive men able to marshal loyal supporters and donors, even in tough economic times, to build esoteric institutions. Each assembled impressive libraries and marketed ancient philosophies in correspondence courses and self-improvement plans, as well as books and essays—all on the premise that a highly developed consciousness and spiritual insight would allow a sincere and dedicated student to achieve success, avoid illness and live in peace.

Curiously, both men were overly trusting and fearful of confrontation with subordinates. When confronted with evidence of an in-house crime, Lewis and Hall would shrug it off with the same phrase, “Just let the matter rest.”

And both were territorial. In the early 1930s, Lewis made a point of assuring his followers that Hall, who frequently lectured on subjects such as “The Doctrine of the Rosicrucians,” was not an expert on Rosicrucian philosophy and should not be taken seriously on such matters.

What set them apart was that Lewis developed an organization with worldwide support and membership. And unlike Hall, who highlighted the idealistic teachings of sages and seers in his lectures and books, Lewis packed his students’ formal lessons with instructions for such things as recalling events of past incarnations, becoming invisible, magnetizing a glass of water with one’s hands to invigorate the glands, treating cancer by directing the spiritual forces of the body through the thumb and index finger, visualizing financial success—or a healthy heart if that organ was ailing. [38] Although Hall frequently sought out the help of healers, he cautioned his followers that “in the battle between bacteria and prayer there is a slight tendency for the bacteria to win in the end. This has been proven in the County Hospital.” [39]

Lewis died of heart disease in 1939 at the age of 55. His organization continues on. [40]

Throughout the 1930s, Hall gave well-attended lectures on Eastern and Western philosophies. The authority in his voice, the magical themes of his books and lectures and his intensely private nature all gave an aura of mystery to everything he said or did, and made him a target of the fantasies and projections of would-be disciples. Some of Hall’s followers insisted that he often scrutinized them with a “third eye,” communicated with them telepathically, even recruited them into his cause by casting strange vibrations their way. Others said the thousands of volumes in his library were arranged in such a way that they told a coherent and seamless narrative of the wisdom teachings of all ages. Still others whispered that he was one of a dozen wise men in the world divinely appointed to shepherd the destiny of mankind. A few suspected that beneath those navy-blue suits Hall was part man and part woman—like the gods he lectured about.

Adherents assumed that a mysterious ring Hall purchased at a New York shop called Esoterica was imbued with magical powers. Hall would only say the stone the size of a quarter was found by one of Napoleon’s soldiers—but at that time it was set into a button discovered on the body of a dead Arab’s burnoose. The reddish-brown carnelian—cut in the shape of a two-headed fowl symbolizing the Gnostic god Abraxas—had been carved in the second century after Christ. Napoleon acquired it and presented it to the Polish Countess Marie Walewska, his mistress at the time. The shop owner claimed to have been a direct descendant of Walewska. [41]

Abraxas, it was said, represented 365 emanations from the First Cause. Carnelians were used by Arabs as shields against men and women possessing the power to harm others by merely looking at them, according to Sir E.A. Wallis Budge, keeper of the Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum, in his book Amulets and Talismans. [42]

Living in the spotlight was not easy for Hall, who struggled to apply his teachings to his own life. His home life was a catastrophe of marital strife, physical ailments, alternative health regimens, and overeating all the while he tried to live up to his image as a “maestro” of practical esoteric philosophy.

Like other spiritual leaders claiming familiarity with secret wisdom such as Madame Blavatsky and Greco-Armenian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, there was a glaring dissonance between Hall’s public image and his private reality. He delegated his business affairs to amateurs and took many of his medical problems to healers with questionable credentials. Although he did not have a university degree, he did not correct those who addressed him as “Dr. Hall.” He advised against trying to develop occult powers, yet dazzled starry-eyed followers with demonstrations of his alleged mind reading and predictions of future events. He claimed he could absorb the contents of books just by sleeping next to them. [43]

Hall’s contradictions at this time were reflected in some of the books and essays he wrote during the 1930s. Their content wavered between witty, urbane philosophy and bizarre accounts of magic and mystery. In Fire, the Universal Deity, he writes that “the auric body of a snake is one of the most remarkable sights that the clairvoyant will ever see, and the secrets concealed within its aura demonstrate why the serpent is the symbol of wisdom among so many nations.” [44] In Magic: A Treatise on Esoteric Ethics, he warns of people who have mastered nature’s forces “to such a degree that they can stop the heartbeat of a person on the other side of the earth with a mental ray, or burn a two-inch hole through a foot and a half of ebony with astral fire...” [45] And in Freemasonry of the Ancient Egyptians, he asserts that Egyptian priests could walk on air, become transparent and live under water. [46]

Hall’s visit to Dawson’s Book Shop near Pershing Square in downtown Los Angeles left a lasting impression on store clerk Warren S. Rogers, who had secured a rare book from abroad that Hall was anxious to get his hands on. However, the book was being held at a local customs office and could only be released to Rogers in person. In order to satisfy Hall, who had arrived in a friend’s Ford coupe, Rogers agreed to travel with them to fetch the book.

It was a tight squeeze, given Hall’s size. “The only way the three of us could fit into the coupe was for me to sit on Mr. Hall’s lap, which I did,” Rogers recalled in his memoirs, My Own Los Angeles, 1894–1982. [47]

Hall recounted various dramatic birth stories. In a version he told often over the years, Hall said he was born a premature blue baby on the morning of March 18, 1901, in one of the first Caesarean operations ever conducted at Nicholls Hospital in Peterborough, in the Canadian province of Ontario. He said the attending physician, a Dr. Lapp, deciding he was dead, placed the infant in a basket, wrote a death certificate, then turned his attention to the infant’s mother, who was in critical condition. Some time later, the baby let out an urgent howl, as though suddenly enlivened by a soul that had dived into the infant’s body from the great beyond. The doctor held him up by his feet and said, “If he lives he’ll be a big fella.” [48]

An improbable story? When questioned, Hall said his birth records were destroyed in a hospital fire. [49] But according to documents, census reports and Peterborough historians, Hall’s mother entered Nicholls Hospital on March 15, and delivered her son three days later at 5:30 a.m. with the assistance of resident physician and nursing school lecturer Dr. William Dixon Scott. She was discharged on March 29. [50] Although one record noting Mrs. Hall’s admission to the hospital lists the word “miscarriage” under a column titled “Disease,” historian John Walter Martyn said, “miscarriage” was used in error to mean premature labor. There is no record of a surgical procedure of any kind. The hospital’s bill for services was $20. [51]

Hall also liked to say that his mother was a physician who launched a career in medicine in 1903 after handing him over to his grandmother when he was two years old. [52] Close family relatives now say Louise was a chiropractic healer who hoped to make a business out of treating miners in the Alaskan gold fields.

The facts about Hall’s confused and insecure childhood are unusual enough. When Hall was born, his parents already were living apart. His father, 29-year-old dentist William S. Hall, was living alone in downtown Peterborough’s finest hotel, the Oriental, and earning a respectable annual salary of about $2,400, according to census records. He moved away from Ontario in 1904 when Manly was three years old and was never heard from again, family members say. [53]

The failed marriage sent Louise spinning into a downward spiral that ended with her decision to leave it all behind and seek her fortune in Alaska. Hall was raised by his grandmother, Florence Louise Palmer, a Victorian-era widow whose husband had owned a varnish factory. [54] After her husband’s death, she sold their assets and then set out to discover America. With Hall in tow, they traveled from town to town, seldom staying in any one of them longer than six months.

Clad in knickerbockers and ribbed cotton stockings, Hall was four years old when his 50-year-old grandmother had him admitted into the U.S. as a Canadian immigrant in July, 1905, in the District of Chicago. [55] They settled briefly in a hotel in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

There, they attended Native American Indian dances, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, and circuses. When Secretary of War William Taft was campaigning for president and made a stop in town, she took her grandson to meet the candidate. The tall man in a starched white vest and long black coat leaned over, patted the young boy on the head and shook his hand. [56]

In 1907, they lived briefly in the California cities of San Francisco, Santa Rosa and San Diego, where their next-door neighbor was the son of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Next they lived in Germantown, Pennsylvania, an old stronghold of Quakers and Mennonites. Then, in Chicago, the young boy began to read voraciously. He and his grandmother, who loved good books, read together by lamplight. Their favorite author was G.A. Henty, whose well-written adventure yarns first introduced Hall to words like “guru” and “astrology.” [57]

Manly and his grandmother, Florence Palmer

When he reached school age, Hall’s grandmother decided he was too advanced for kindergarten and enrolled him into the first grade, where he opened a textbook to find the letters of the alphabet an inch high in various bold colors. “When I was asked to identify these letters and pronounce them in class, I was decidedly embarrassed,” Hall recalled in an essay years later. “At home at that particular period, grandmother and I were deep into Victor Hugo.”

Hall was quickly promoted to third grade, where he was confronted with multiplication tables. “This did not hold my attention,” he said, “for at that time I was handling most of grand-mother’s bank accounts.” [58]

His grandmother enjoyed entertaining friends. On rainy evenings, when she wanted to impress them, she would select curios from a little cabinet chock-full of interesting items collected over the years and present them with the skill of a professional curator. It was a pastime that Hall would eventually make an important part of his own life.

In 1914, Woodrow Wilson was president and Hall’s grandmother moved into a genteel boarding house about three blocks from the White House in Washington. [59] Among the boarders was Señora Carenza, a Spanish woman who used her mysterious gift as a “burn stroker” to cure second- and third-degree burns of others at no charge. “We noticed that Señora Carenza always stroked the burn very lightly and toward her own heart,” Hall recalled. “While doing so, she whispered a little verse. With my natural curiosity, I finally persuaded her to recite the verse for me in English.” Her secret of Spanish folk healing, which Hall said worked wonders, was this: “Three wise men come out of the East, Melchior, Gaspar, and Balthazar. Go heat, come cold. Come cold, go heat. Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.” [60]

In 1917, Hall and his grandmother moved again, this time to New York, where Hall joined a military training program and found work as a clerk at an insurance company in the financial district of lower Manhattan. [61] Along with a starting salary of $30 a month, he received some stern advice from the firm’s vice president: When a young man becomes associated with an old and reputable firm, it is his duty to live an exemplary life. His associates should be chosen for their respectability. He should attend church and have a savings account. He should select a girl of good character and avoid debt. Loyalty to the company established a bond that would last a lifetime.

One day, the head bookkeeper with a spotless record of 47 years was found dead at his desk. A standing clock was delivered to the man’s home by way of appreciation for his services. Within a few weeks, he was never mentioned again. [62]

Hall quit, believing there must be a better way to earn a living.

His next job, which was slightly better than the first, involved clerical work at a Wall Street firm. Disillusionment with that company turned to deep depression with the sudden death of his grandmother. “Here I was starting out in life with no background that would give any particular support or strength to the problems I was facing and would face,” Hall recalled. “I looked around and could not see any way in which I could get the instruction and help I needed. There did not seem to be anyone to turn to.” [63]

All that changed the day he wandered into the dilapidated “House of a Thousand Memories” at 493 Sixth Avenue. The Martinka brothers, Antonio and Francis, presided over this emporium for stage magicians, who were all the rage on vaudeville stages. Among its frequent patrons was escape artist and stage magician Harry Houdini, one of the greatest showmen of all time.

The front door opened to store counters and glass cases stacked high with magician’s equipment. Behind the store was a large room with a small stage surrounded by chairs for audiences that gathered on weekend afternoons to enjoy examples of the conjurer’s art. Beyond that room was a yard where magicians boarded pets used in their performances—doves, rabbits, goldfish, dogs and cats. Houdini wanted to board an elephant, but found the facilities too small.

One Saturday, Houdini dropped by and delighted Hall and other admirers with an old favorite. The short, stocky and slightly bow-legged magician stood on the backroom stage and seemed to make a package of needles and a spool of thread appear from nowhere. Then he put a half dozen needles and a foot of thread in his mouth, and started chewing with gusto. Hall was amazed when he started pulling the thread from his mouth. The needles were threaded about an inch apart.

In Martinka’s back rooms, Hall said he engaged in late-night debates with Houdini, Howard Thurston and other famous magicians over whether miracles could be wrought without stage paraphernalia. Their talks invariably led to discussions about the practices of East Indian fakirs, Egyptian snake charmers and Native American medicine men.

Houdini told Hall that the only reason he could perform his feats was that he copied them from Asian jugglers and magicians. He also admitted that he did not know exactly how they did their tricks, only how to mechanically reproduce their effects. In Hall’s mind, that was practically conceding that there were supernatural aspects about such things that he did not understand. [64]

Houdini went on to buy Martinka’s, which had been serving magicians since just after the Civil War. He also launched a high-profile public crusade to expose as fraudulent all psychics, fortune-tellers, and spirit mediums, a class that flourished after World War I as friends and relatives of slain soldiers desperately tried to communicate with their loved ones on the other side. [65] To Houdini, spiritualism was nothing more than mental intoxication resulting from the seductive words and promises of con artists.

Hall, however, headed west, firm in the belief that the universe was stranger and more interesting than Houdini wanted to admit. Over the next 10 years Hall would undergo striking intellectual and personal changes, and render himself an adventurer in the realm of the spiritual self. By the late 1930s Hall was enjoying the richest years of his life.

Hall began spicing up his holiday season lectures with astrological horoscopes of the world, the United States and California. Usually, the forecasts were so ambiguous and obvious that they left plenty to chance. But on May 20, 1934, he told his congregation sometime between 1940 and 1942, the civilized nations of the world would be plunged into cataclysmic political unrest and violence. [66] His source was a booklet published in 1860 by Dr. L.D. “Astrological Doc” Broughton, a medical physician and astrologer from Washington, D.C. who was famous for having predicted the assassination of President Lincoln. In that booklet, Broughton declared that the return of Uranus to the constellation Gemini in 1942 would undoubtedly be accompanied by years of anguish and strife at home and abroad. [67]

In the meantime, Hall was making new, powerful allies during his travels. At the Pythagorean Society in New York in 1935, Hall met a serious student of Platonism and reincarnation who would become His Grace, Athenagoras I, spiritual leader of the Greek Orthodox Church. They became devoted friends; when meeting on the street the tall, husky and bearded religious leader would throw his arms around Hall. Many of Hall’s books were in the Patriarchate Library in Istanbul. At one Easter service in New York, Hall walked in solemn procession with Athenagoras I. [68]

Also in 1935, Robert Andrews Millikan, a Nobel Prize winner and chairman of the executive council of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, invited Hall to attend a fund-raising dinner for troubled youths. The guest speaker was former President Herbert Hoover. The master of ceremonies was comedian and actor Joe E. Brown. Sponsors included pioneer motion picture director Cecil B. DeMille, one of many influential Freemasons in Hollywood at the time. [69]

Such high-profile public appearances lent further credibility to the man who behind the scenes was quietly investigating shamanistic formulas for bending the laws of nature. He studied the magical aspects of minerals and gems, concluding that manic states could be balanced by keeping a piece of lead in one’s pocket; nervous tension could be remedied with green tourmaline and copper, depression by silver and zinc. [70] He slept with his head to the north so that the magnetic currents of his body would “correspond with the vaster currents moving about and through the earth.” [71] He applied Pythagorean theories about the therapeutic value of music, and entertained the idea that people in bathing suits would get more out of stirring string music than heavily clothed individuals because bare skin responds positively to pleasant sounds. [72] Hall also claimed that without too much training, students with the right frame of mind could learn to read playing cards placed face down on a table. [73]

Hall was profiled in an extensive Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine article, published in August 1935, as a world-class expert “in the so-called Mystery Schools of the ancient world which, instead of nurturing a semi-barbarism as most modern historians assume, was really in most ways superior to the addle-pated present.”

“Now, it is Mr. Hall’s idea to attempt to reconstruct these Mystery Schools,” said the article by George Addison. “He holds that this can be accomplished by decoding the ciphers, symbols, hieroglyphs, fables, myths, and legends which abound in classical writings. He further hopes that some key documents escaped destruction and, in the course of time, will be found in the Sahara Desert, Gobi Desert, and possibly in the ruined cities of Central America.”

The discovery of such codes, Hall predicted, might be of more value in setting man on the right path of knowledge than all the accomplishments of science and technology.

At the time, Hall also was trying with the help of actor friends to break into the movie business, which he believed should have been incorporating more mythical and magical themes in its major motion pictures. In 1939, eight years after Tod Browning’s adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula hit the silver screen, Hall wrote a proposed sequel and dispatched it to Stanley Bergerman, associate producer of The Mummy.

The nine-page treatment would have made Stoker proud. It begins where the first movie left off: Dr. Van Helsing driving a stake through the vampire’s heart. Only there’s a twist. The “vampire howls with fiendish glee and shams death,” Hall wrote, because the assassination attempt occurred seconds after nightfall, when Dracula is invulnerable.

Three decades later, after old age and death has claimed the lives of Dracula’s foes, “the lid of the great sarcophagus rises by some mysterious mechanism,” Hall wrote. “The gruesome hand bearing the ring of Voivode Dracula appears and the vampire slowly rises. He has had no blood for many years, therefore he is now a white-haired man, aged and bearded. His face is hollow with sleep of years and his clothes are rotted about him.”

Portrait of Hall as guru by Schuyler Crail, 1938

Meanwhile, in Argentina, Señorita Martinez has a frightening secret: she has always known the sinister count was not dead. Worse, she learns he plans to visit her home along the La Plata River “in a strange vessel.”

Later, “there is a mist upon the river,” Hall wrote. “Through the fog suddenly appears a magnificent black streamlined yacht bearing the name Nemesis III. The yacht enters the south basin slowly. . . ”

A group of detectives dispatched to investigate the craft discovers that its crew is dead. “There is apparently nothing alive but a great black cat that hisses violently at them,” Hall wrote.

A shadowy figure creeps along the dock. [74]

Eventually, Martinez and her closest admirer learn the horrible truth: Dracula “has come to claim his bride according to the blood-pact made thirty years earlier.” [75]

Hall never mentioned the manuscript, which was offered for sale on eBay in Canada in 2007 for $800.

In an interview in the late 1930s with entertainment industry reporter Philip K. Scheuer, Hall explained, “There is a ready-made audience of 10 million for definitely metaphysical themes in the United States ... It is the richest untouched field of entertainment that remains to be exploited, for nearly every human being has an experience he cannot explain, yet cannot forget! And in such times as these, we turn eagerly toward that which may provide a clue, a key, to the Answer.” [75]

In an essay during this period, Hall wrote, “With such problems as reincarnation, karma, evolution, the super physical perceptions in man, the motion picture studio could make the world familiar with these subjects in a way no book, college professor, or anyone else could possibly do. Presenting them in the form of entertainment is one of the most powerful methods of converting the public mind, because after all, what you see in the pictures is so real, you never question it.” [76]

He was not the only person who felt that way. Fantasies and mythical horror stories swept through movie studios after Walt Disney’s full-length cartoon fairy tale Snow White broke box-office records in 1938. In the works were The Wizard of Oz, a full-length motion picture based on the 1900 children’s novel by practicing Theosophist L. Frank Baum, and Disney’s Fantasia, which would feature a segment starring Mickey Mouse as a hapless sorcerer’s apprentice. [77]

According to Hall, famous musical composer Leopold Stokowski, who had been retained by Disney to help develop a score and images for Fantasia, showed up at his home one day seeking advice on how various scenes should be filmed. “There are vague incidents in the film as I suggested them to Stokowski,” Hall recalled in an essay decades later. He did not elaborate. [78]

Warner Brothers tapped Hall for story ideas and solid advice on myth and magic that could be developed into screenplays. Hall set right to work, pounding out a series of imaginative stories for the silver screen and dispatching them to Bergerman’s office on Sunset Boulevard. One of them celebrated the life of the 18th-century mystic adventurer Compte de Saint Germain. Others included an untitled outline for a mystery that involves a murderer who develops a paralyzed arm after fatally shooting a woman with a similar malady and stealing her jewels.