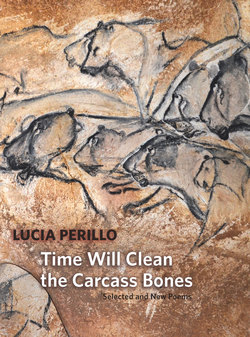

Читать книгу Time Will Clean the Carcass Bones - Lucia Perillo - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеInseminator Man

When I call him back now, he comes dressed in the silver of memory,

silver coveralls and silver boots

and a silver hard hat that makes no sense.

The cows could not bombard his head,

though the Lilies and the Buttercups, the Jezebels and Mathildas,

avenged their lot in other ways

like kicking over a pail or stomping on his foot.

Blue welt, the small bones come unknitted,

the big toenail a black cicada peeling off its branch.

It wasn’t hard to understand their grudge, their harbor

of accumulated hurts —

imagine lugging those big tits everywhere, year after year.

Balloons full of wet concrete

hung between their legs like scrotums, duplicate and puffed.

I remember grappling with the nipples

like a teenage boy in a car’s backseat

and how the teats would always fill again before I could complete

their squeezing-out.

At night, two floors above them in the half-demolished barn,

my hands ached and made me dream of cows that drained

until the little stool rose off the ground and I found myself

dog-paddling in milk.

The summer after college I’d gone off to live with women

who’d forsworn straight jobs and underwear and men.

At night the ten of us linked hands

around a low wire-spool table before we took our meal of

vegetables and bread.

Afterward, from where the barn’s missing wall

opened out on Mad River, which had no banks but cut an oxbow

flush with the iridescent swale of the lower fields,

I saw women bathing, their flanks in the dim light

rising like mayflies born straight out of the river.

Everyone else was haying the lower field when he pulled up,

his van unmarked and streamlined like his wares:

vials of silvery jism from a bull named Festus

who — because he’d sired a Jersey that took first place

at the Vermont State Fair in ’53 —

was consigned to hurried couplings with an old maple stump

rigged up with white fur and a beaker.

When the man appeared I was mucking stalls in such heat

that I can’t imagine whether or not I would have worn

my shirt

or at what point it became clear to me that the bull Festus

had been dead for years.

I had this idea the world did not need men:

not that we would have to kill them personally,

but through our sustained negligence they would soon die off

like houseplants. When I pictured the afterlife

it was like an illustration in one of those Jehovah’s Witness magazines,

all of us, cows and women, marching on a promised land

colored that luminous green and disencumbered by breasts.

I slept in the barn on a pallet of fir limbs,

ate things I dug out of the woods,

planned to make love only with women, then changed my mind

when I realized how much they scared me.

“Inseminator man,” he announced himself, extending a hand,

though I can’t remember if we actually spoke.

We needed him to make the cows dry off and come into new milk:

we’d sell the boy-calves for veal, keep the females for milkers,

and Festus would live on, with this man for a handmaid,

whom I met as he was either going into the barn or coming out.

I know for a fact he didn’t trumpet his presence,

but came and went mysteriously

like the dove that bore the sperm of God to earth.

He wore a hard hat, introduced himself before I took him in,

and I remember how he graciously ignored my breasts while still

giving them wide berth.

Maybe I wore a shirt or maybe not: to say anything

about those days now sounds so strange.

We would kill off the boys, save the females for milkers I figured

as I led him to the halfway mucked-out stalls, where he

unfurled a glove past his elbow

like Ava Gardner in an old-movie nightclub scene.

Then greased the glove with something from a rusted can

before I left him in the privacy of barn light

with the rows of cows and the work of their next generation

while I went back outside to the shimmering and nearly

blinding work of mine.