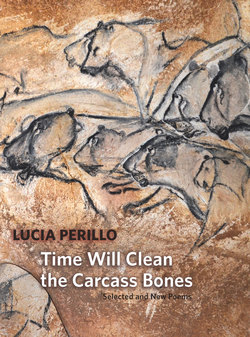

Читать книгу Time Will Clean the Carcass Bones - Lucia Perillo - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNeedles

So first there’s the chemo: three sticks, once a week,

twenty-six weeks.

Then you add interferon: one stick, three times a week,

forever.

And then there’s the blood tests. How many blood tests?

(Too many to count.)

Add all the sticks up and they come down to this: either

your coming out clean

or else… well, nobody’s talking

about the B-side,

an or else that plows through your life like a combine

driven at stock-car speed,

shucking the past into two piles: things that mattered

and things that didn’t.

And the first pile looks so small when you think of

everything you haven’t done —

never seeing the Serengeti or Graceland, never running

with the bulls in Spain.

Not to mention all the women you haven’t done yet!—

and double that number of breasts.

Okay—

you’ve got a woman, a good woman, make no mistake.

But how come you get just one woman when you’re getting

many lifetimes’ worth of sticks?

Where is the justice in that? You feel like someone

who’s run out of clean clothes

with laundry day still half a week away; all those women

you tossed in the pile

marked things that didn’t matter, now you can’t help but

drag them out.

Like the blond on trail crew who lugged the chain saw

on her shoulder up a mountain

and bucked up chunks of blighted trees — how could you

have forgotten

how her arms quaked when the saw whined and the muscles

went liquid in her quads,

or the sweaty patch on her chest where a mosaic formed

of shiny flies and moss?

Or that swarthy-haired dancer, her underpants hooked

across her face like the Lone Ranger,

the one your friends paid to come to the table, where

she pawed and made you blush:

How come yer getting married when you could be muff-diving

every night?

At college they swore it was John Dewey, they swore

by the quadruped Rousseau,

and it took cancer to step up and punch your gut

before you figured

that all along immortal truth’s one best embodiment

was just

some sixteen-year-old table-dancing on a forged ID

at Ponders Corners.

You should have bought a red sports car, skimmed it under

the descending arms at the railroad crossing,

the blond and brunette beside you under its moonroof

and everything smelling of leather —

yes yes—this has been your flaw: how you have always

turned away from the moment

your life was about to be stripped so the bone of it

lies bare and glittering.

You even tried wearing a White Sox cap to bed but its bill

nearly put your wife’s eye out.

So now you’re left no choice but going capless, scarred;

you must stand erect;

you must unveil yourself as a bald man in that most

treacherous darkness.

You remember the first night your parents left town, left

you home without a sitter.

Two friends came over and one of them drove the Mercury

your dad had parked stalwartly

in the drive (you didn’t know how yet) — took it down

to some skinny junkie’s place

in Wicker Park, cousin of a friend of a cousin, friend

of a cousin of a friend,

what did it matter but that his name was Sczabo.

Sczabo! —

as though this guy were a skin disease, or a magician

about to make doves appear.

What he did was tie off your friends with a surgical tube,

piece of lurid chitterling

smudged with grease along its length. Then needle, spoon —

he did the whole bit,

it was just like in the movies, only your turn turned you

chicken (or were you defiant? — )

Somebody’s got to drive home, and that’s what you did

though you’d never

made it even as far as the driveway’s end before your dad

put his foot over the transmission hump

to forestall some calamity he thought would compromise

the hedges.

All the way back to Evanston you piloted the Mercury

like General Montgomery in his tank,

your friends huddled in the backseat, spines coiled,

arms cradled to their ribs —

as though each held a baby being rocked too furiously

for any payoff less than panic.

It’s the same motion your wife blames on some blown-out

muscle in her chest

when at the end of making love she pitches violently,

except instead of saying

something normal like god or jesus she screams ow! ow!

and afterward,

when you try sorting out her pleasure from her pain,

she refuses you the difference.

Maybe you wish you took the needle at Sczabo’s place —

what’s one more stick

among the many you’ll endure, your two friends not such

a far cry from being women,

machines shaking and arching in the wide backseat

as Sczabo’s doves appeared —

or so you thought then, though now you understand

all the gestures the body will employ

just to keep from puking. Snow was damping the concrete

and icing the trees,

a silence stoppered in the back of your friends’ throats

as you let the Mercury’s wheel pass

hand over hand, steering into the fishtails, remembering

your dad’s admonition:

when everything goes to hell the worst you can do

is hit the brakes.