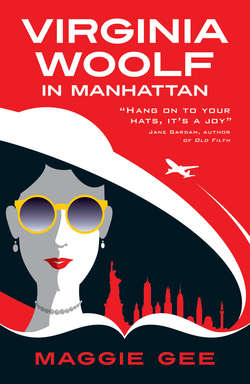

Читать книгу Virginia Woolf in Manhattan - Maggie Gee - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление15

ANGELA

Back in the room, I ordered tea; luke-warm water and teabags arrived. The lack of competence invigorated her.

VIRGINIA

‘Tea was always appalling abroad. France, Germany. So nothing’s changed.’

ANGELA

I felt defensive about my century.

‘Actually, this isn’t typical. It’s just a rather poor hotel.’

VIRGINIA

‘Is it poor? Really? Then why did you choose it?’

ANGELA

Virginia was sitting on the bed. Her long elegant frame made it look short and narrow.

I contemplated the difficulties of explaining the perils of internet deals. First I must explain the internet. No, put it off until tomorrow. ‘Because it’s cheap,’ I said

She had draped my coat over the single armchair. I sank down beside her on the same twin bed, leaving a respectful gap between us.

VIRGINIA

‘Oh. Are you poor?’

ANGELA

I was furious! ‘Certainly not.’

Her interest was anthropological: I was just a human from another era. No, I wasn’t real for her.

But I was real. Money is a touchy subject. If she was going for frankness, so would I. ‘You ought to be massively rich by now. Royalties, and rights, and so forth.’

VIRGINIA

‘If so, they certainly haven’t told me. Possibly I was hard to contact.’

ANGELA

I tried not to think she was mocking me. Something to do with the class difference maybe. The elongated vowels of her ‘really’. The accent of someone who had never had to work.

All very well for her to time-travel and end up here with no means of support.

VIRGINIA

I was chortling with pleasure at the nerve of this woman. I loved the fact that she could talk about money. So many women are incapable of doing so. Brazen, yes, but invigorating. All the same – did she think they’d been sending me cheques?

ANGELA

I blushed with shame. She was definitely laughing. I wanted her to think me intelligent. For one second I almost felt – hatred.

‘So you don’t have any money at all, Virginia?’ (Why should I pussyfoot around with the ‘Mrs’?) ‘That’s rather – inconvenient.’ I snickered, mirthlessly. Two could play at that game.

I poured myself another cup of tea, without looking to see if she needed a refill.

VIRGINIA

She had gone too far. She was a vulgar woman. But I could wipe the smile off her face. ‘I didn’t take any money with me – on my last day.’

ANGELA

I did feel bad.

‘Sorry, Virginia.’

VIRGINIA (severely)

‘Mrs Woolf!’

ANGELA (taken by surprise)

‘Sorry.’

No, it was absurd, I would not – kow-tow. ‘But you know, we are in the twenty-first century.’

VIRGINIA (not understanding)

‘Surely good manners are still important.’

ANGELA

‘Yes. My name is Angela. Just in case you want to use it.’

(Pause.)

‘Wait a minute … what’s that in your pocket?’ (Disappointed) ‘Oh I suppose it’s just a stone.’

VIRGINIA

‘There is nothing of interest to you in my pockets.’

ANGELA

I saw from her face she was lying to me!

Hauteur punctured by childish guilt, a smidgin of fear mixed with laughter – she looked like Gerda aged one and a half, hiding her banana under the sofa. Which must explain what happened next. Looking back on it I can hardly believe it, but this is what happened. We had a fight!

‘There is.’ I reached for the bulges in her jacket, she tried to turn her back on me – we had a brief tussle. I was tussling with Woolf, I was stronger, of course – she had been dead for a while! – yet something had changed since she first arrived, when I had touched her hand and there was nothing there. Her body no longer felt liquid, boneless. She was panting a little. No, she was laughing.

There was a hard object in each pocket, straining the frayed tweed of her suit.

VIRGINIA

‘They’re books, that’s all. I like to keep them with me.’

(Oddly, the struggle made me giggle. I had not been touched for such a long time. I played with my brothers, long long ago. When I was a child, and things were easy, before Mother died and the house went dark.)

‘I mean, they are mine. I did write them. I even published them. I have a right.’

(Why was I justifying myself to her? She was becoming a parent figure. Poor Dr Freud would have something to say, in his flickering, subtle, shrunken way –

– How very late I came to love him. Like fathers, only after they die … I loved my father, but the noise, the groaning, the hurricane that shook the doors. Then, when he’d gone, I could think, in the silence, I could feel for him, I could dare to love him. After Freud died, I began to read him.)

ANGELA

‘My God. To the Lighthouse. What a glorious copy.’

I could hardly believe what I saw on the bed. As she pulled it out it had fallen open. I gazed at the print, the Hogarth typeface, the fresh, dense cream of the pages. And then I closed it, and it really sank in.

‘Virginia! It’s a first edition.’

There it was, Vanessa’s lovely design, the grey swirls of the waves below, the few plain strokes to denote the lighthouse, the black dots swarming in different densities to show the light blazing up in a fan. All around it, the lighthouse wall. ‘It’s worth a fortune. What’s the other one?’

VIRGINIA (stays silent, lost in thought)

ANGELA

‘Virginia! Show me the other one! I am excited! It’s incredible!’

VIRGINIA (starting, and staring hard at the book before handing it over)

‘Somehow my books came to find me.’

(Angela opens some pages, amazed.)

VIRGINIA (dreamily)

‘They were waiting for me in this strange world, new as the day when they came from the printers. We have other lives, I think, I hope …

‘Orlando was a joy to write, like a wild gallop across strange country … such a happy autumn till my pen rebelled. But somehow, yes, one finished things …’

ANGELA

‘Orlando! Sorry, this is overwhelming.

Could I take a photograph? Just this once? For the books, not you?’

I was a tourist! I did, right there, with her perched on the bed, Orlando on her lap, To the Lighthouse beside her. Virginia Woolf, with two first editions!

The balance of power had shifted between us, with the fight – the fight! – and now the photograph. But one long white hand went over her face. And I saw her gather herself. Her force.

(I must have somehow pressed the wrong button, because when I looked later, there was nothing there.)

VIRGINIA

‘Kindly never do that again. I cannot, will not, be photographed.’

ANGELA

She was furious. She stood up tall. She blocked the light. She detested me.

‘Sorry,’ I said. ‘I knew that, actually. It’s in the – ’

I stopped. It was in the biographies. She didn’t know the biographies. So thick, so intimate, so many.

‘Sorry,’ I said, again. I stretched out my hand, palm up, placating.

VIRGINIA

‘Let’s talk about more interesting things. Did you say – these – were valuable?’

ANGELA

‘Immensely. Of course, you might not want to sell them.’

We looked at each other, and it was decided.

VIRGINIA (hand half-extending)

‘You said your name was … Angela?

–You want me to call you Angela?’

ANGELA (still slightly wary)

‘As I was trying to explain to you, no-one says “Mrs” in the twenty-first century.’

VIRGINIA

‘I see. Then you may call me Virginia. I had a niece called Angelica.’

ANGELA

‘My full name is Angela Lamb. That’s the name on my book jackets.’

(I say this automatically now, having noticed that often, when I meet a stranger – an un-literary stranger, that is to say – they ask ‘Do you write under your own name?’

Virginia was hardly un-literary.)

VIRGINIA

‘I think I shall call you “Mrs Lamb”.’ (Slight smile.)

ANGELA

‘Please don’t!’

(They turn slightly towards one another.)

VIRGINIA

‘Angela.’

ANGELA

‘Virginia.’

VIRGINIA (with gaiety)

‘Let us go out and make some money!’

(After a second, they shake hands.)