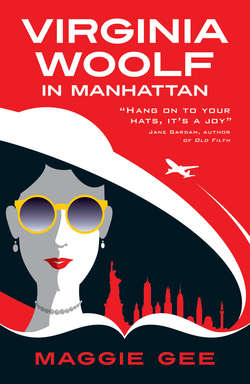

Читать книгу Virginia Woolf in Manhattan - Maggie Gee - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление21

ANGELA

Goldstein’s was staffed with polite, good-looking young men who hovered purposefully in pale suits, gracing the customers with discreet smiles that hinted at shared passions. The shop was so beautiful I felt rather shy. It wasn’t like English secondhand bookshops with piles of dusty books in corners. It was high and airy, with a gallery, a large dark table in the middle of the room for customers to inspect the books, and display cases around the walls. They showed exquisite single copies, dotted in careful asymmetry, like blowing leaves in a Hiroshige print.

And what did I see, on the right-hand wall, winking at me from behind the glass? A copy of To The Lighthouse, with the familiar Vanessa Bell book jacket. The lighthouse tower, the radiating beams, and Virginia’s name in capitals. (How different it felt seeing it now. Of course I had read her name on book jackets hundreds of times, but never before with this intimate jolt of recognition – the woman was waiting for me just around the corner!)

My heart lifted, then my heart sank – of course it was good to see it displayed among the jewels of the collection. But if they had one copy, would they want another?

She was next to Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. And there was Orlando on the other side!

A clean-cut, shiny-haired young man wavered closer.

‘Good afternoon, Ma’am. May I assist you?’

‘I’m interested in Virginia Woolf.’

‘We have a quite good collection, as you see. And over here, there’s a nice copy of A Room of One’s Own.’

I trotted obediently after him. There was yet another first edition, sporting the original dust jacket, slightly browned at the edges but the colours still bright, a clock on an ink-blue background. Perhaps the clock meant the time was right for women to have money and a room of their own.

Now once again, Virginia needed money. And a room of her own in New York, which I was sorting. Mine was much too small for us.

(Too small for me, as well. I had left it too late to book my flights and then BA Business Class was £4,000! I was haemorrhaging money for Gerda’s fees, so I’d suddenly thought ‘Oh, sod BA’ and booked a package through lastminute.com. Unfortunately the hotel was the Waddington. OK, it got full marks for location, but it hadn’t been renovated in decades, no mini-bar, no desk. I wasn’t too bothered, I would be in the library. But when Virginia came along I suddenly saw it through her eyes – a yellow, chemical, ugly box. Yet she’d stared out of the window as if she was in heaven. Is all life heaven, compared to death?)

Would her opinions unsettle my life?

Would she always, somehow, make me feel a failure?

I dismissed the thought. I was a best-selling author, with two degrees – she didn’t have one, though they called her ‘the cleverest woman in England’ – and I went to the gym and looked after myself. Whereas she looked as though the only exercise she did was dragging herself through a hedge backwards. I had good hair. Ok, this was shallow, but – I had a daughter. She did not. Leonard had forbidden her to have children in case it drove her mad again – though I knew my daughter had kept me sane.

A pang of love: my darling Gerda.

I remembered I hadn’t emailed her.

‘ … Ma’am?’

‘Oh, sorry, I was day-dreaming.’

‘Room of One’s Own costs – let me check. Cinnamon boards and the Vanessa Bell jacket – you are aware she is Woolf’s sister? Yes, it’s not cheap, because it is quite unique – $12,800.’

‘Excellent,’ I said, and he looked at me strangely, but of course I was deducing how much her books might earn us. And ‘quite unique’ was not English, but this wasn’t the time to point it out.

‘You’re interested?’

‘How much is To the Lighthouse?’

‘First trade edition with a pristine dust jacket, $28,000. Four hundred and somethingth of eight hundred signed copies. You really couldn’t hope for a better copy.’

‘Could I actually have a look at it?’

His movements brisker, he went to the case and tenderly removed the book, then led me over to the big dark table, seated me with a small flourish, and placed the thing reverently before my chair.

It was a clone of Virginia’s copy, though her jacket was unyellowed by time, her colours truer, the pages whiter. And on the inside fly-leaf, his tapering finger pointed to her signature.

I had seen photos, but never the real thing. It was smaller, quieter than I imagined.

‘I thought she signed in violet ink?’

‘It is purple – but the years fade it.’

The writing was – what? Business-like. The opposite of bohemian. Slanting, clever, fluent, neat. (Of course, I would have to get her to sign them! Why hadn’t I thought of that before?)

‘Would you like to hold it? It’s quite exciting. Part of literary history.’ I thought, I’ve touched enough literary history today to last me for a while, young man.

‘So $28,000 is the top price a copy of To the Lighthouse would fetch? I mean, it seems to tick all the boxes – signed, first edition, book jacket.’

‘Well – unless someone found a personalised copy. Not that it would, as you say, tick boxes.’

The merest hint of professional disdain.

‘What would a personalised copy be?’

‘I don’t think this is likely to happen – most Woolf first editions are accounted for, and something like this would already have surfaced – but if someone were to turn up with a book she had signed for a friend, rather than a signature done to order – you know she pre-signed for her American publisher? – that would be something very special. Signed copies were more unusual then. Especially if it were something meaningful. Best of all, a message to someone famous – Lytton Strachey, for instance, are you familiar with him? –Vita Sackville-West – or, best of all, Leonard.’

‘I see.’ And I was starting to see. How we could actually make ourselves rich. My expectations had been too modest. ‘Great! Well, thank you for showing me that.’

‘You don’t want to look inside?’ He was taken aback – but he couldn’t know that I had to think about the actual author, sitting round the corner, Virginia Woolf in her slightly smelly glory, eating a hamburger with fries. I had to keep her off the streets of New York until she had money, and knew how to behave.

I am a socially anxious person. Because of my background, which was working-class, despite my profession and education, despite my accent, despite my money, my house in Hampstead and daughter at the Abbey, I try to behave, I try to fit in.

Virginia was never going to help that happen.

I would need a contact here at Goldstein’s. ‘I’ll be returning tomorrow or the next day,’ I called to the young man’s slender, faintly affronted back as he walked off to return the book. He closed the case with a definite ‘click’.

‘Uh … Sir?’ I tried, emollient. ‘I have a friend. She has some books I think would be of interest to you.’

His smile was automatic, with the briefest eye contact. ‘Perhaps she could submit the details by email? I’ll give you my card.’

He gave me his card. (Of course they must have heard it all day long, people coming in or phoning up, making coy, slightly vain allusions to books they were sure would be ‘of interest’ to Goldstein’s, and when they saw them, most of them weren’t.)

‘She’s an old lady,’ I smiled at him. ‘She doesn’t use the internet. I think she would like to drop by in person.’

‘As you like,’ he said, with the faintest shrug, and his hair was so tidy, his shirt so white, I did wonder what he would make of Virginia.

We would have to deal with the pondweed odour.

I found her sitting good as gold in her café, investigating a tomato-shaped squeezer of ketchup, a quarter of which she had ejected on her plate, a dense, blood-red, viscous hillock of sauce. ‘Have you seen this?’ she inquired, gaily.

The burger had been a great success! She told me Angelica would have loved it.

Virginia ate six burgers in the next week.